Abstract

Background:

Advanced biliary cancer is often treated with fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy. In this study, we evaluated the efficacy and tolerability of a combination of S-1, an oral fluoropyrimidine prodrug, and oxaliplatin in patients with metastatic biliary cancer.

Methods:

Patients with histologically confirmed metastatic biliary cancer and no history of radiotherapy or chemotherapy were enrolled. Oxaliplatin was administered intravenously (130 mg m−2), followed by 14-day administration of oral S-1 (40 mg m−2 twice daily) with a subsequent 7-day rest period every 21 days. Pharmacokinetic analysis of S-1 was performed at cycle 1. Patients were genotyped for CYP2A6 polymorphisms (*1, *4, *7, *9 or *10), and pharmacokinetic and clinical parameters compared according to the CYP2A6 genotype.

Results:

In total, 49 patients were evaluated, who received a median of four cycles. The overall response rate was 24.5%. Median progression-free and overall survival was 3.7 and 8.7 months, respectively. The most common haematological grade 3 out of 4 toxicity was neutropenia (14%), while non-hematological grade 3 out of 4 toxicities included anorexia (14%), nausea (12%), asthenia (10%), vomiting (10%), and diarrhoea (4%). Biotransformation of S-1 (AUC0−24 h of 5-fluorouracil/AUC0−24 h of tegafur) was 1.85-fold higher for the *1/*1 group than for the other groups (90% confidence interval 1.37–2.49). Diarrhoea (P=0.0740), neutropenia (P=0.396), and clinical efficacy (response rate, P=0.583; PFS, P=0.916) were not significantly associated with CYP2A6 genotype, despite differences in 5-FU exposure.

Conclusion:

The combination of S-1 and oxaliplatin appears to be active and well tolerated in patients with metastatic biliary cancer, and thus is feasible as a therapeutic modality. CYP2A6 genotypes are associated with differences in the biotransformation of S-1. However, the impact of the CYP2A6 polymorphism on variations in clinical efficacy or toxicity requires further evaluation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Biliary tract cancer (BTC), including cancer of the gallbladder and the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts, is one of the most aggressive human malignancies. Gemcitabine and fluoropyrimidine constitute the backbone of palliative chemotherapy (Hezel and Zhu, 2008). 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) displays clinical activity, both alone and in combination with platinum-based agents, in single arm phase II studies (Ducreux et al, 1998; Choi et al, 2000). Oral fluoropyrimidine derivatives, including capecitabine and uracil-tegafur (UFT), have been shown to be active as single agents, as well as in conjunction with cisplatin (Kim et al, 2003; Ikeda et al, 2005; Park et al, 2005).

S-1, an oral prodrug of 5-FU composed of tegafur, 5-chloro-2, 4-dihydroxypyridine (CDHP; gimestat), and potassium oxonate (otastat), shows clinical efficacy in patients diagnosed with various solid tumours, including biliary tract cancers (Park et al, 2009; Sasaki et al, 2009). Combinations of S-1 and cisplatin have also yielded modest response rates and tolerable toxicity profiles (Kim et al, 2008b; Kang et al, 2010).

The pharmacokinetic and toxicity profiles of S-1 differ with ethnicity (Hirata et al, 1999; Hoff et al, 2003; Chu et al, 2004). The principal dose-limiting toxicities are diarrhoea in Caucasian and myelosuppression in Asian patients (Hirata et al, 1999; Cohen et al, 2002). These differences may be attributable to genetic variations in CYP2A6 encoding a cytochrome P450 enzyme that has a major role in the biotransformation of tegafur to 5-FU (Ikeda et al, 2000). One clinical study demonstrated an association of the CYP2A6*4 allele with exposure to 5-FU in non-small-cell lung cancer patients receiving S-1, while another study suggested that exposure to CDHP, which affects the metabolism of 5-FU, is the key determinant of variability in 5-FU efficacy following S-1 administration (Fujita et al, 2008; Kaida et al, 2008).

The primary objective of the present study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of S-1 in combination with oxaliplatin chemotherapy in patients with metastatic BTC and objective response rate was the primary endpoint. The secondary objective was to evaluate the relationships between pharmacokinetics, clinical activity and tolerability of S-1-based chemotherapy and CYP2A6 genotypes.

Patients and Methods

Eligibility criteria

Patients with histologically confirmed recurrent or metastatic cancer of the biliary tract were eligible, provided that they met the following criteria, including at least one unidimensionally measurable lesion according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) guidelines Version 1.0, age between 18 and 70 years, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0–2, adequate haematological (haemoglobin ⩾9.0 g dl−1, absolute neutrophil count (ANC) ⩾1.5 × 109 l−1, and platelet count ⩾100 × 109 l−1), hepatic (total bilirubin ⩽1.5 mg dl−1, serum transaminase ⩽3 × upper normal limit or ⩽5 × upper normal limit in cases of hepatic metastases), and renal (serum creatinine ⩽1.5 mg dl−1) functions, no history of radiation therapy or chemotherapy, including S-1 or oxaliplatin treatment within 6 months, and no history of gastrointestinal operations, including gastrectomy or pancreaticoduodenectomy. Patients were excluded if they had central nervous system metastasis, gastrointestinal obstruction, bleeding or sensory neuropathy greater than grade 2, according to the National Cancer Institute of Common Toxicity Criteria (NCI CTC) Version 3.0. Creatinine clearance was calculated using the Cockcroft–Gault equation (Cockcroft and Gault, 1976). The protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee, and all patients provided written informed consent before enrollment. This study was conducted using the Good Clinical Practice guidelines, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments.

Study design and treatment

This was a single centre phase II study performed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of the S-1 and oxaliplatin combination therapy. S-1 was administered orally at a dose of 40 mg m−2 twice daily for 14 days, followed by a 7-day rest period. S-1 doses were calculated in milligrams per square metre of body surface area, and rounded down to the nearest 5 or 10 mg. For pharmacokinetic analysis, S-1 was given only once on day 1 of cycle 1. Beginning on day 2, S-1 was administered twice daily. Oxaliplatin was administered intravenously at 130 mg m−2 for 2 h on day 2 of cycle 1, and day 1 of cycle 2 and subsequent cycles. Treatment was repeated every 21 days, and continued for a maximum of 9 cycles in the absence of progressive disease, development of unacceptable toxicity, or patient refusal.

Doses of S-1 and oxaliplatin were reduced based on the extent of haematologic and non-hematologic toxicities evaluated before each treatment cycle, according to NCI CTC toxicity scale Version 3.0. At the first occurrence of grade 3 thrombocytopenia or grade 4 neutropenia lasting <5 days, S-1 treatment was interrupted, but was resumed at the same dose after resolution to grade 1 or better. At the second or third occurrence of the same haematologic toxicity with similar severity, treatment was interrupted, followed by 25 or 50% dose reduction of S-1 and oxaliplatin (to 100 and 85 mg m−2, respectively) in subsequent cycles. If the haematologic toxicity recurred with similar severity after adequate dose reduction, treatment was discontinued. In cases of grade 3 or 4 non-hematologic toxicity, treatment was interrupted, followed by a 25 or 50% dose reduction, respectively. The oxaliplatin dose was modified in cases where patients developed grade 2 neurosensory toxicity. Treatment was interrupted until toxicity resolved to grade 1 or better, with reduction of the oxaliplatin dose to 100 mg m−2 in subsequent cycles. In patients experiencing a second occurrence of grade 2 neurosensory toxicity, treatment was interrupted, and the oxaliplatin dose reduced to 85 mg m−2. Treatment was discontinued if patients experienced recurrence of grade 2 neurosensory toxicity after two oxaliplatin dose reductions, if oxaliplatin therapy was delayed for >2 weeks because of toxicity, or if patients developed grade 3 or higher neurosensory toxicity.

Efficacy and safety assessments

All patients who received at least one cycle of treatment were subjected to efficacy and safety assessments. Response rate, the primary endpoint, was evaluated according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) Version 1.0 (Therasse et al, 2000). Evaluation of tumours was performed every two cycles. Chemotherapy was discontinued in cases of disease progression, unacceptable toxicity or withdrawal of consent. Adverse drug reactions were graded according to National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria Version 3.0.

Pharmacokinetic assay

Blood samples (about 10 ml) were collected in heparinised tubes at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h after the first single dosage of S-1 administered during cycle 1. Tubes were centrifuged (3500 r.p.m., 8 min, 4°C), and plasma immediately separated and transferred as three aliquots into storage cryotubes, which were frozen at −80°C until analysis. Plasma concentrations of all compounds were determined using liquid chromatographic–tandem mass spectrometry. Tegafur, FU, and CDHP were analysed on the API 3000 LC/MS/MS system (MDS Sciex, Concord, Ontario, Canada). Plasma concentration data were used to calculate pharmacokinetic parameters, including area under the curve from 0 to 24 h (AUC0−24 h) and maximum concentration (Cmax), by the linear trapezoid method using WinNonlin (Professional Network Version 5.2; Pharsight Corporation, Mountain View, CA, USA).

CYP2A6 genotyping assay

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood using a specific DNA preparation kit (QIAamp Blood Mini Kit; Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Genotypes of CYP2A6*1, *7, *9 and *10 allelic variants were determined using the multiplex minisequencing (SNaPshot, ABI PRISM SNaPshot Multiplex Kit; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) method. Briefly, the full-length CYP2A6 gene was amplified using a pair of primers, specifically, 5′-CTCTCCCCTGGAACCCCCAG-3′ and 5′-GCACTTATGTTTTGTGAGACATCAGAGACAA-3′. PCR was performed on a 9700 thermal cycler (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster city, CA, USA) under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, followed by 30 cycles of 98°C for 20 s, 64°C for 30 s, 72°C for 3 min 30 s, and a final elongation step at 72°C for 10 min. The 7.5 kb PCR product was used as a template for the SNaPshot reaction, which contained the following sequencing primers: CYP2A6-48T>G (*9), 5′-GGCTGGGGTGGTTTGCCTTT-3′; CYP2A6 6600G>T (*10), 5′-GGAAGCTCATGGTGTAGTTT-3′; and CYP2A6 6558T>G (*7), 5′-CTCCCAGTCACCTAAGGACA-3′. Genotype analyses were performed with GeneMapper (Version 3.7) software (Applied Biosystems). For genotyping the CYP2A6 deletion allele (*4), allele-specific amplification and restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis were performed, as described previously (Nakajima et al, 2001).

Statistical analyses

Standard descriptive and analytical methods were used to describe the patient population and their baseline characteristics. This trial was designed using Fleming's single-stage Phase II procedure to test the null hypothesis that the true objective response rate was <15%, with a sample size sufficient to reject it when the true objective response rate was >35% with an 80% power and using a level of α=5% (one-sided test), and required a sample size of 44 patients (Machin et al, 1997; Kim et al, 2008b). We assumed a dropout rate of 10%, making the required number of patients 49.

To analyse the effects of CYP2A6 genotypes, the pharmacokinetic parameters of S-1 were log-transformed and compared using mixed model analysis of variance (ANOVA). To evaluate CYP2A6 genotype-drug interactions, the differences in log-transformed mean values between wild type (*1/*1) and variants (single or double) were calculated, and both point estimates and 90% confidence interval (CI) back-transformed to obtain geometric mean ratios, along with CI values for the ratios. Progression-free survival (PFS) was calculated from the commencement of chemotherapy to date of disease progression or death from any cause, and overall survival (OS) calculated from the start of chemotherapy to date of death from any cause. Survival analyses were performed using the Kaplan–Meier method with the log-rank test. Data analyses were performed using the Statistical Software Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 14.0; Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

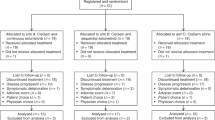

From September 2006 to January 2008, we enrolled a total of 49 patients with histologically confirmed recurrent or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the biliary tract (Table 1). No patient had previously received radiation therapy or chemotherapy, including S-1 or oxaliplatin. Median patient age was 52 years (range, 23–68 years), and 31 patients (63%) were male. Most patients (94%) showed good performance status with ECOG scale values of 0–1. All patients had good renal function, and mean creatinine clearance was 97.40 ml min−1 (range, 57.13–198.0 ml min−1). A total of 30 patients (61%) were diagnosed with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, and 10 (20%) with gallbladder cancer. In all, 40 patients (82%) had metastatic abdominal lymphadenopathy, with the liver being the most common metastatic organ (67%).

Efficacy

Among the 49 study patients, 45 were evaluated for response. The remaining four subjects were lost to follow-up and hence were not assessable. Partial response was observed in 24.5% (12 out of 49) and stable disease in 34.7% (17 out of 49) of patients. The overall response rate in the intention-to-treat population was 24.5% (95% (CI), 12.5–36.5%; Table 2). Patients with gallbladder cancer tended to show a higher response rate than those with intra- or extra-hepatic cholangiocarcinoma, but the difference was not statistically significant. At a median follow-up duration of 20 months (range, 9.4–25.6 months), median PFS and OS for all patients were 3.7 months (95% CI: 1.7–5.7 months) and 8.7 months (95% CI: 4.8–12.6 months), respectively (Figure 1). We observed no significant survival differences with respect to tumour location (data not shown).

Drug exposure and safety

The 49 patients underwent a total of 216 treatment cycles (median, 4 cycles), 212 of which were assessable for toxicity. The frequencies of haematological and non-haematological toxicities are summarised in Table 3. The most common (>5%) grade 3 out of 4 haematological toxicity was neutropenia with an incidence of 12% (6 out of 49). However, no febrile neutropenia was observed. The most common non-hematological grade 3 out of 4 toxicity was anorexia (7 out of 49, 14%), followed by nausea (6 out of 49, 12%), vomiting (5 out of 49, 10%), asthenia (2 out of 49, 4%), stomatitis (2 out of 49, 4%), and diarrhoea (2 out of 49, 4%).

A total of 54 treatment cycles (26%, 54 out of 207 cycles) were delayed in 24 patients. Chemotherapy doses were reduced for 65 out of 207 cycles (31%) in 26 patients. The median dose intensities were 315.1 mg m−2 per week (range, 106.4–373.3 mg m−2 per week) for S-1 and 39.4 mg m−2 per week (range, 24.2–43.3 mg m−2 per week) for oxaliplatin, with relative dose intensities of 84.4 and 91.1%, respectively.

Relationships among pharmacokinetic parameters, clinical efficacy, toxicity of S-1, and CYP2A6 genotypes

CYP2A6 genotypes were analysed in all 49 patients, and full pharmacokinetic data were obtained for 48 of the patients. Wild-type homozygotes (CYP2A6*1/*1) were detected in 14 patients, and single and double variants in 28 and 7 patients, respectively. The allele frequencies of CYP2A6*4, *7, *9, and *10 were 10.2, 8.2, 19.4, and 4.1%, respectively. These values did not deviate significantly from the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium.

In 48 patients, the 5-FU level reached peak plasma concentrations (Cmax) about 4 h after administration of S-1. The pharmacokinetic parameters are presented in Table 4. Plasma concentrations of 5-FU tended to be higher in the CYP2A6 *1 homozygotes than patients with variant gene types (Figure 2). Specifically, Cmax, 5−FU and AUC0−24 h, 5−FU for CYP2A6 variant types were 70% (90% CI: 55–88%) and 74% (90% CI: 56–98%) those for *1 homozygotes (Table 4). On the other hand, FT plasma concentrations were lower in the CYP2A6 *1 homozygotes, compared with those in patients with genetic variations (Figure 2); The Cmax,FT and AUC0−24 h,FT values for CYP2A6 *1 homozygotes were 17% (90% CI: 2–33%) and 37% (90% CI: 19–58%) higher than those with variant genes (Table 4). CDHP plasma concentrations were similar in both groups.

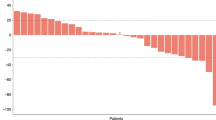

The ratio between exposure to 5-FU and FT (AUC0−24 h of 5-FU/ AUC0−24 h of FT) was 0.0710±0.0433 in the wild-type group and 0.0331±0.0160 in patients with single or double variants (Table 4, Figure 3), yielding a 1.85-fold higher metabolic ratio (90% CI: 1.37–2.49) in the wild-type group. However, comparison of the frequencies of diarrhoea and neutropenia between wild type and variants revealed that the CYP2A6 *1/*1 genotype was not significantly associated with any grade of diarrhoea (wild type, 5 out of 13, vs variant type, 7 out of 35; P=0.0740) or neutropenia (wild type, 4 out of 13, vs variant type, 7 out of 35; P=0.396). In addition, exposure to 5-FU (AUC0−24 h, 5−FU) was not significantly correlated with severity of diarrhoea or neutropenia (Figure 4).

Discussion

This study evaluated the efficacy and safety of S-1 and oxaliplatin in Korean patients with metastatic biliary tract carcinoma. The response rate was 24.5%, and median PFS and OS were 3.7 and 8.7 months, respectively, similar to results obtained from trials of S-1 combinations with cisplatin and oxaliplatin (Kim et al, 2008b; Oh et al, 2008). The frequencies of diarrhoea (4%) and neutropenia (14%) exceeding grade 3 were comparable with those of other studies, which used similar dosages of S-1 and oxaliplatin (Yamada et al, 2008; Zang et al, 2009).

Recently, survival gain in biliary tract cancers with gemcitabine-based chemotherapy was reported. Moreover, a combination of gemcitabine and cisplatin displayed benefits over gemcitabine monotherapy in a randomised, phase III trial (Valle et al, 2010). A small-scale randomised phase II trial showed that survival rates with gemcitabine and oxaliplatin surpassed those with fluorouracil and folinic acid in unresectable gall bladder cancer (Sharma et al, 2010). On the other hand, several phase II trials have supported the utility of 5-FU-based containing regimens for biliary tract cancers (Eckel and Schmid, 2007). Although gemcitabine-based chemotherapy may be the preferred treatment based on recent phase III trials, it is not evident whether gemcitabine surpasses fluoropyrimidine in terms of efficacy (Kim et al, 2008a). Combination chemotherapy consisting of gemcitabine, 5-FU derivatives and platinum analogue regimens led to response rates between 20 and 30% and median survival of 8–12 months (Verslype et al, 2008).

The recorded overall response of 24.5% meant that our study did not meet its primary endpoint response rate of 35%. However, some biologic features of biliary tract cancers should be considered. First, response rates and survival differ significantly according to the primary site of the tumour, and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma has the worst prognosis (Park et al, 2009). The proportion of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma was substantially higher than expected (61%), which may have influenced the overall response rate. Second, many studies have used tumour control rate (defined as stable disease, complete or partial response) to assess efficacy owing to the aggressive nature of advanced biliary tract cancer. We recorded a tumour control rate of 59.2%, which is comparable with data from previous studies with S-1 and cisplatin (Kim et al, 2008b). Third, we recently showed that gemcitabine was better than S-1 as a doublet partner for platinum agents in advanced biliary cancers (Kang et al, 2010). However, gemcitabine was associated with higher toxicities, especially neutropenia and thrombocytopenia. As fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy induces lower haematological toxicities and decreased tendency of biliary tract cancer-related infections, including cholangitis and liver abscess, S-1 use may be favored in a subset of patients (Kim et al, 2008a). Moreover, S-1 offers the convenience of oral administration, in contrast to the weekly intravenous administration of gemcitabine. Therefore, well-designed randomised phase III trials are required to compare fluoropyrimidine plus platinum combination with gemcitabine plus platinum combination chemotherapy in terms of efficacy and safety.

Despite these advantages, S-1 pharmacokinetics is subject to interindividual variability, which is explained by the pharmacogenetics of CYP2A6 (Goh et al, 2008). The variant genotypes of CYP2A6 display decreased baseline enzyme activity, leading to reduced 5-FU formation. We categorised pharmacokinetic parameters as ‘wild type’ (*1/*1) and ‘variant type’ (single and double variant) genotypes, consistent with pharmacogenetic studies on nicotine, another substrate of CYP2A6 (Schoedel et al, 2004; Nakajima et al, 2006; Mwenifumbo et al, 2007). On comparing the ratio between AUC0−24 h of 5-FU and AUC0−24 h of FT by CYP2A6 genotype, this ratio was 1.85-fold greater in the*1/*1 group than the variant-type group. A previous study reported that non-small cell lung cancer patients with CYP2A6*4 alleles, which complete lack relevant enzymatic activity, show significantly lower plasma concentrations of 5-FU (Kaida et al, 2008). In addition to CYP2A6*4 alleles, CYP2A6*7, *9, and *10 displayed decreased enzyme activity. Our present observations have expanded the application of CYP2A6 genotyping by including various alleles in the interpretation of S-1 pharmacokinetics.

Despite differences in exposure, the CYP2A6 genotype was not significantly associated with clinical efficacy or incidence of toxicity, suggesting that the pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationships of 5-FU are complicated. Studies using various schedules and formulations of 5-FU have reported a correlation between exposure to 5-FU and toxicity, particularly diarrhoea (Cohen et al, 2002; Chu et al, 2004; Ajani et al, 2005; Gusella et al, 2006; Gamelin et al, 2008). Conversely, other studies have been unable to establish an association between the AUC of 5-FU and toxicity after S-1 administration (Hirata et al, 1999). This lack of association may also be attributed to the other constituents of S-1. The action of oxonate, which inhibits the orotate phosphoribosyl-transferase (OPRT) enzyme in intestinal tissue and decreases the occurrence of diarrhoea, may be related to interindividual differences (Shirasaka et al, 1993; Peters et al, 2003). The clinical efficacy of fluoropyrimidines, including S-1, is influenced by thymidylate synthase, which may confound the association between 5-FU exposure and clinical efficacy (Ichikawa et al, 2004). A recent investigation reported a correlation between the CYP2A6 genotype and efficacy of S-1-based chemotherapy in advanced gastric cancer (Kong et al, 2009). However, pharmacokinetic data for clarifying the exposure-effect relationship were not evaluated.

S-1 is mainly used in Korea and Japan, whereas capecitabine is often used in Western countries. In a study on the efficacy of capecitabine and oxaliplatin in advanced biliary tract cancers, Nehls et al (2008) observed a tumour control rate of 77%, which is higher than that obtained in our study. However, it must be noted that patient characteristics between the two studies differed, since we analysed more cases of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, which has the worst prognosis among the biliary tract cancers. An additional finding is that the recommended dose of S-1 for Asians is higher than that for Caucasians (Hoff et al, 2003). This has been explained by the fact that Caucasians show a higher frequency of wild-type CYP2A6 and suffer from gastrointestinal toxicities. Another Korean group recently reported adequate efficacy and safety with 50 mg m−2 S-1 twice a day in combination with 130 mg m−2 oxaliplatin for colorectal cancer (Kim et al, 2009).

In conclusion, the present results suggest that a combination of S-1 and oxaliplatin is active and safe for patients with advanced biliary tract cancer. At present, gemcitabine is favored as the backbone for chemotherapy in biliary tract cancers, based on efficacy studies. However, an oral 5-FU based regimen, such as capecitabine or S-1, may be preferable in terms of convenience. Large-scale studies are required to properly address this issue. Our findings further indicate that differences in the CYP2A6 genotype may affect individual pharmacokinetics of S-1, but do not have a significant impact on clinical efficacy or toxicity.

Change history

29 March 2012

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Ajani JA, Faust J, Ikeda K, Yao JC, Anbe H, Carr KL, Houghton M, Urrea P (2005) Phase I pharmacokinetic study of S-1 plus cisplatin in patients with advanced gastric carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 23 (28): 6957–6965

Choi CW, Choi IK, Seo JH, Kim BS, Kim JS, Kim CD, Um SH, Kim YH (2000) Effects of 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin in the treatment of pancreatic-biliary tract adenocarcinomas. Am J Clin Oncol 23 (4): 425–428

Chu QS, Hammond LA, Schwartz G, Ochoa L, Rha SY, Denis L, Molpus K, Roedig B, Letrent SP, Damle B, DeCillis AP, Rowinsky EK (2004) Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of the oral fluoropyrimidine S-1 on a once-daily-for-28-day schedule in patients with advanced malignancies. Clin Cancer Res 10 (15): 4913–4921

Cockcroft DW, Gault MH (1976) Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron 16 (1): 31–41

Cohen SJ, Leichman CG, Yeslow G, Beard M, Proefrock A, Roedig B, Damle B, Letrent SP, DeCillis AP, Meropol NJ (2002) Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of once daily oral administration of S-1 in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res 8 (7): 2116–2122

Ducreux M, Rougier P, Fandi A, Clavero-Fabri MC, Villing AL, Fassone F, Fandi L, Zarba J, Armand JP (1998) Effective treatment of advanced biliary tract carcinoma using 5-fluorouracil continuous infusion with cisplatin. Ann Oncol 9 (6): 653–656

Eckel F, Schmid RM (2007) Chemotherapy in advanced biliary tract carcinoma: a pooled analysis of clinical trials. Br J Cancer 96 (6): 896–902

Fujita K, Yamamoto W, Endo S, Endo H, Nagashima F, Ichikawa W, Tanaka R, Miya T, Araki K, Kodama K, Sunakawa Y, Narabayashi M, Miwa K, Ando Y, Akiyama Y, Kawara K, Kamataki T, Sasaki Y (2008) CYP2A6 and the plasma level of 5-chloro-2, 4-dihydroxypyridine are determinants of the pharmacokinetic variability of tegafur and 5-fluorouracil, respectively, in Japanese patients with cancer given S-1. Cancer Sci 99 (5): 1049–1054

Gamelin E, Delva R, Jacob J, Merrouche Y, Raoul JL, Pezet D, Dorval E, Piot G, Morel A, Boisdron-Celle M (2008) Individual fluorouracil dose adjustment based on pharmacokinetic follow-up compared with conventional dosage: results of a multicenter randomized trial of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 26 (13): 2099–2105

Goh BC, Soo RA, Lim S, Zhang J, Furuie T, Urrea PD, Rosen LS (2008) Inter-ethnic variability of S-1 pharmacokinetics (PK) and correlation with CYP2A6 phenotyping. J Clin Oncol ASCO Annu Meet Proc 26: (abstract 2507)

Gusella M, Crepaldi G, Barile C, Bononi A, Menon D, Toso S, Scapoli D, Stievano L, Ferrazzi E, Grigoletto F, Ferrari M, Padrini R (2006) Pharmacokinetic and demographic markers of 5-fluorouracil toxicity in 181 patients on adjuvant therapy for colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 17 (11): 1656–1660

Hezel AF, Zhu AX (2008) Systemic therapy for biliary tract cancers. Oncologist 13 (4): 415–423

Hirata K, Horikoshi N, Aiba K, Okazaki M, Denno R, Sasaki K, Nakano Y, Ishizuka H, Yamada Y, Uno S, Taguchi T, Shirasaka T (1999) Pharmacokinetic study of S-1, a novel oral fluorouracil antitumor drug. Clin Cancer Res 5 (8): 2000–2005

Hoff PM, Saad ED, Ajani JA, Lassere Y, Wenske C, Medgyesy D, Dwivedy S, Russo M, Pazdur R (2003) Phase I study with pharmacokinetics of S-1 on an oral daily schedule for 28 days in patients with solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 9 (1): 134–142

Ichikawa W, Takahashi T, Suto K, Yamashita T, Nihei Z, Shirota Y, Shimizu M, Sasaki Y, Hirayama R (2004) Thymidylate synthase predictive power is overcome by irinotecan combination therapy with S-1 for gastric cancer. Br J Cancer 91 (7): 1245–1250

Ikeda K, Yoshisue K, Matsushima E, Nagayama S, Kobayashi K, Tyson CA, Chiba K, Kawaguchi Y (2000) Bioactivation of tegafur to 5-fluorouracil is catalyzed by cytochrome P-450 2A6 in human liver microsomes in vitro. Clin Cancer Res 6 (11): 4409–4415

Ikeda M, Okusaka T, Ueno H, Morizane C, Furuse J, Ishii H (2005) A phase II trial of Uracil-tegafur (UFT) in patients with advanced biliary tract carcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol 35 (8): 439–443

Kaida Y, Inui N, Suda T, Nakamura H, Watanabe H, Chida K (2008) The CYP2A6*4 allele is determinant of S-1 pharmacokinetics in Japanese patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Pharmacol Ther 83 (4): 589–594

Kang M, Lee J, Kim T, Lee S, Park D, Seo D, Kim M (2010 ) Randomized phase II trial of S-1 and cisplatin versus gemcitabine and cisplatin in advanced biliary tract adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol 28 (15s): abstr 4029

Kim HS, Park MJ, Uhm JE, Lee Y, Lee HY, Kang EM, Lee J, Park SH, Park JO, Lim HY, Kang WK, Park YS (2009) A phase I trial of S-1 with oxaliplatin in patients with relapsed and metastatic colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis 24 (11): 1311–1316

Kim MJ, Oh DY, Lee SH, Kim DW, Im SA, Kim TY, Heo DS, Bang YJ (2008a) Gemcitabine-based versus fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy with or without platinum in unresectable biliary tract cancer: a retrospective study. BMC Cancer 8: 374

Kim TW, Chang HM, Kang HJ, Lee JR, Ryu MH, Ahn JH, Kim JH, Lee JS, Kang YK (2003) Phase II study of capecitabine plus cisplatin as first-line chemotherapy in advanced biliary cancer. Ann Oncol 14 (7): 1115–1120

Kim YJ, Im SA, Kim HG, Oh SY, Lee KW, Choi IS, Oh DY, Lee SH, Kim JH, Kim DW, Kim TY, Kim SW, Heo DS, Yoon YB, Bang YJ (2008b) A phase II trial of S-1 and cisplatin in patients with metastatic or relapsed biliary tract cancer. Ann Oncol 19 (1): 99–103

Kong SY, Lim HS, Nam BH, Kook MC, Kim YW, Ryu KW, Lee JH, Choi IJ, Lee JS, Park YI, Kim NK, Park SR (2009) Association of CYP2A6 polymorphisms with S-1 plus docetaxel therapy outcomes in metastatic gastric cancer. Pharmacogenomics 10 (7): 1147–1155

Machin C, Campbell M, Fayers P, Pinol A (1997) Sample Size Tables for Clinical Studies 2nd edn. Blackwell Science: Oxford and London, UK

Mwenifumbo JC, Sellers EM, Tyndale RF (2007) Nicotine metabolism and CYP2A6 activity in a population of black African descent: impact of gender and light smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend 89 (1): 24–33

Nakajima M, Fukami T, Yamanaka H, Higashi E, Sakai H, Yoshida R, Kwon JT, McLeod HL, Yokoi T (2006) Comprehensive evaluation of variability in nicotine metabolism and CYP2A6 polymorphic alleles in four ethnic populations. Clin Pharmacol Ther 80 (3): 282–297

Nakajima M, Kwon JT, Tanaka N, Zenta T, Yamamoto Y, Yamamoto H, Yamazaki H, Yamamoto T, Kuroiwa Y, Yokoi T (2001) Relationship between interindividual differences in nicotine metabolism and CYP2A6 genetic polymorphism in humans. Clin Pharmacol Ther 69 (1): 72–78

Nehls O, Oettle H, Hartmann JT, Hofheinz RD, Hass HG, Horger MS, Koppenhofer U, Hochhaus A, Stieler J, Trojan J, Gregor M, Klump B (2008) Capecitabine plus oxaliplatin as first-line treatment in patients with advanced biliary system adenocarcinoma: a prospective multicentre phase II trial. Br J Cancer 98 (2): 309–315

Oh SY, Lee GW, Kim HG, Kim TH, Kim HJ, Kang JH (2008) Phase II trial of S-1 in combination with oxaliplatin in previously untreated patients with recurrent or inoperable biliary tract cancer. Chemotherapy 54 (6): 479–484

Park I, Lee JL, Ryu MH, Kim TW, Chang HM, Lee SS, Sohn BS, Kim EK, Park do H, Suh DW, Lee SK, Kim MH, Lee J (2009) Efficacy and safety of S-1 monotherapy in patients with advanced biliary tract adenocarcinoma: retrospective analysis of 162 patients. Oncology 76 (2): 126–132

Park KH, Choi IK, Kim SJ, Oh SC, Seo JH, Choi CW, Kim BS, Shin SW, Kim YH, Kim JS (2005) The efficacy of epirubicin, cisplatin, uracil/tegafur, and leucovorin in patients with advanced biliary tract carcinoma. Cancer 103 (11): 2338–2343

Peters GJ, Noordhuis P, Van Kuilenburg AB, Schornagel JH, Gall H, Turner SL, Swart MS, Voorn D, Van Gennip AH, Wanders J, Holwerda U, Smid K, Giaccone G, Fumoleau P, Van Groeningen CJ (2003) Pharmacokinetics of S-1, an oral formulation of ftorafur, oxonic acid and 5-chloro-2,4-dihydroxypyridine (molar ratio 1:0.4:1) in patients with solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 52 (1): 1–12

Sasaki T, Isayama H, Yashima Y, Yagioka H, Kogure H, Arizumi T, Togawa O, Matsubara S, Ito Y, Nakai Y, Sasahira N, Hirano K, Tsujino T, Tada M, Kawabe T, Omata M (2009) S-1 monotherapy in patients with advanced biliary tract cancer. Oncology 77 (1): 71–74

Schoedel KA, Hoffmann EB, Rao Y, Sellers EM, Tyndale RF (2004) Ethnic variation in CYP2A6 and association of genetically slow nicotine metabolism and smoking in adult Caucasians. Pharmacogenetics 14 (9): 615–626

Sharma A, Dwary AD, Mohanti BK, Deo SV, Pal S, Sreenivas V, Raina V, Shukla NK, Thulkar S, Garg P, Chaudhary SP (2010) Best supportive care compared with chemotherapy for unresectable gall bladder cancer: a randomized controlled study. J Clin Oncol 28 (30): 4581–4586

Shirasaka T, Shimamoto Y, Fukushima M (1993) Inhibition by oxonic acid of gastrointestinal toxicity of 5-fluorouracil without loss of its antitumor activity in rats. Cancer Res 53 (17): 4004–4009

Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, Verweij J, Van Glabbeke M, van Oosterom AT, Christian MC, Gwyther SG (2000) New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst 92 (3): 205–216

Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, Cunningham D, Anthoney A, Maraveyas A, Madhusudan S, Iveson T, Hughes S, Pereira SP, Roughton M, Bridgewater J (2010) Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med 362 (14): 1273–1281

Verslype C, Prenen H, Van Cutsem E (2008) The role of chemotherapy in biliary tract carcinoma. HPB (Oxford) 10 (3): 164–167

Yamada Y, Tahara M, Miya T, Satoh T, Shirao K, Shimada Y, Ohtsu A, Sasaki Y, Tanigawara Y (2008) Phase I/II study of oxaliplatin with oral S-1 as first-line therapy for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 98 (6): 1034–1038

Zang DY, Lee BH, Park HC, Song HH, Kim HJ, Jung JY, Kim JH, Kim HY, Kwon JH, Hwang SW, Park SR, Park CH, Kim KO, Kim MJ, Jang KM (2009) Phase II study with oxaliplatin and S-1 for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 20 (5): 892–896

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the Korea Health 21 R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare and Family Affairs (Seoul, Republic of Korea; nos. A030001, A062254) and the Asan Institute for Life Sciences (Seoul, Republic of Korea; 2006-231).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, Kp., Jang, G., Hong, Y. et al. Phase II study of S-1 combined with oxaliplatin as therapy for patients with metastatic biliary tract cancer: influence of the CYP2A6 polymorphism on pharmacokinetics and clinical activity. Br J Cancer 104, 605–612 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2011.17

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2011.17

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Polymorphisms of genes encoding drug transporters or cytochrome P450 enzymes and association with clinical response in cancer patients: a systematic review

Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology (2019)

-

A phase II study of preoperative chemoradiation with tegafur-uracil plus leucovorin for locally advanced rectal cancer with pharmacogenetic analysis

Radiation Oncology (2017)

-

Associations between CYP2A6 polymorphisms and outcomes of adjuvant S-1 chemotherapy in patients with curatively resected gastric cancer

Gastric Cancer (2017)

-

A phase II study of capecitabine and oxaliplatin combination chemotherapy in patients with inoperable adenocarcinoma of the gall bladder or biliary tract

BMC Research Notes (2016)

-

A dose-finding study for oxaliplatin, irinotecan, and S-1 (OIS) in patients with metastatic or recurrent gastrointestinal cancer

Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology (2016)