Abstract

Background:

The enumeration of circulating tumour cells (CTC) has prognostic significance in patients with metastatic breast cancer (MBC) and monitoring of CTC levels over time has considerable potential to guide treatment decisions. However, little is known on CTC kinetics in the human bloodstream.

Methods:

In this study, we compared the number of CTC in both 7.5 ml central venous blood (CVB) and 7.5 ml peripheral venous blood (PVB) from 30 patients with MBC starting with a new line of chemotherapy.

Results:

The number of CTC was found to be significantly higher in CVB (median: 43.5; range: 0–4036) than in PVB (median: 33; range: 0–4013) (P=0.001). When analysing samples pairwise, CTC counts were found to be significantly higher in CVB than in PVB in 12 out of 26 patients with detectable CTC. In contrast, only 2 out of 26 patients had higher CTC counts in PVB as compared with CVB, whereas in 12 remaining patients no significant difference was seen. The pattern of CTC distribution was independent of the sites of metastatic involvement.

Conclusion:

A substantial difference in the number of CTC was observed between CVB and PVB of patients with MBC. Registration of the site of blood collection is warranted in studies evaluating the role of CTC assessment in these patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Over the past 10 years, a vast body of evidence has emerged supporting the use of circulating tumour cells (CTC) as a promising, new prognostic factor in the clinical management of patients with metastatic breast, colorectal and prostate cancer (Cristofanilli et al, 2004; Cohen et al, 2008; De Bono et al, 2008). Several studies strongly suggest an equal role in early breast cancer (Ignatiadis et al, 2008; Pierga et al, 2008; Rack et al, 2010). In addition, molecular characterisation of CTC has been shown to have the potential to serve as a powerful pharmacodynamic marker to predict tumour sensitivity to specific targeted treatments (Meng et al, 2004b; de Bono et al, 2007; Attard et al, 2009).

Several approaches for the detection, enumeration and isolation of CTCs in blood samples of patients with various types of cancer have been developed (Mostert et al, 2009). Only the CellSearch System (Veridex, Raritan, NJ, USA), a semi-automated system for the immunomagnetic enrichment of CTC based on their expression of epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM), immunolabeling and image cytometry, has gained approval of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). With this technique two or more CTC per 7.5 ml blood are detected in ca. 60% of patients with metastatic breast cancer (MBC). Furthermore, a cutoff of five CTC or more per 7.5 ml of blood has been applied to distinguish between good and worse prognosis in patients with MBC (Cristofanilli et al, 2004; Hayes et al, 2006).

Previous studies have addressed several analytical sources of variability in CTC measurements by the CellSearch System, however, little is known about the biological variability and kinetics of CTC in the human bloodstream (Allard et al, 2004; Riethdorf et al, 2007; Tibbe et al, 2007; Kraan et al, 2011). Given the physical mismatch between malignant epithelial cells, typically having a diameter of 10–30 μm, and human capillaries, on average only 3–8 μm in diameter ((Boulpaep, 2003) (p. 464)), considerable variability in the number of CTC throughout the circulation, both in time and space, can be anticipated. Experiments in mouse models have shown that CTC transiently peak in the circulation after injection in the tail vein or left cardiac ventricle, after which they steadily increase in parallel with the development of micrometastases in lymph nodes and/or bone marrow over several weeks of time (Goodale et al, 2009). In line with these observations, CTC have been shown to disappear from the bloodstream in the majority of patients with localised breast cancer within days after surgical removal of the primary tumour (Krag et al, 1999; Meng et al, 2004a; Biggers et al, 2009; Sandri et al, 2010). Furthermore, for most solid malignancies typical patterns of metastasis can be predicted based on the anatomical localisation of the primary tumour (Weiss, 1992). In a recent study evaluating the impact of different surgical interventions for colorectal liver metastases on CTC levels in anatomically discrete vascular compartments, CTC appeared to be localised more abundantly to the hepatic macrocirculation whereas significantly fewer enter the peripheral circulation, suggesting that the liver and the lungs act as the major site of retention for CTC in these patients (Jiao et al, 2009).

With this study, we wanted to investigate anticipated differences in the occurrence, number and characteristics of CTC in different vascular compartments of patients with breast cancer. As quantitative cutoff values in the number of CTC are used to distinguish between patients with good and worse prognosis, differences in the number of CTC according to the site of blood sampling might be of direct clinical importance. Furthermore, differences in numbers and in characteristics of CTC in different vascular compartments might help to gain insight into the biology of these cells and the metastatic process.

Materials and Methods

Patients and sample collection

Consecutive patients with MBC with either untreated metastatic disease or progressive metastatic disease before the start of a new line of treatment, who had an implanted central venous vascular access system, were recruited from November 2009 till November 2010. Appropriate local ethics committee approval was obtained and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

CTC enumeration and characterisation

The CTC were isolated and enumerated using the CellSearch System (Veridex) in both 7.5 ml central venous blood (CVB) – obtained from the implanted vascular device – and 7.5 ml peripheral venous blood (PVB) – obtained from an antecubital vein. Both blood samples were drawn simultaneously in CellSave Preservative Tubes (Immunicon Inc., Huntingdon Valley, PA, USA), stored at room temperature and processed within 72 h. Paired samples were analysed in parallel using the CellSearch Circulating Tumour Cell kit (Veridex) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Criteria for an EpCAM positive object to be identified as a CTC include a round-to-oval morphology, a visible nucleus (DAPI+), positive staining for cytokeratin and negative staining for CD45. Each sample was analysed independently by two readers (DP and GVdE). Questionable interpretations were evaluated again until consensus was reached. As a measure for the size of CTC, the geometrical area of each individual cell was estimated based on the two longest perpendicular diameters according to the following formula: π × A/2 × B/2 (with A and B being the two longest perpendicular diameters measured on screen) (Figure 2A).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 16.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A two-sided P⩽0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Normality was tested with a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, assuming normality of data if P>0.1. In the case of normal distribution in all subgroups, equality of means was tested using Student's t-test. The Mann–Whitney U-test, Kruskal–Wallis test or Wilcoxon Signed Ranks test were used to assess differences between non-parametric distributed variables. Correlations between continuous variables were analysed with Spearman's correlation statistics. The Pearson's χ2-test was used to assess the relation between categorical variables.

Results

A total of 30 patients were recruited into this study. This group comprised of four patients with primary MBC and 26 patients with MBC progressing under treatment. The median age of the patient population was 62 (range: 40–85) years. Almost all patients had diffuse metastatic involvement and most patients with progressive metastatic disease were extensively pretreated with multiple lines and types of systemic treatments. Other clinicopathological data are summarised in Table 1.

Comparison of the number of CTC in different vascular compartments

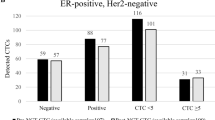

The number of CTC was measured in different vascular compartments. In all patients CTC were assessed in CVB and PVB. Figure 1 and Table 2 represent the results. In four (13%) patients no CTC were found in any of the vascular compartments. The median number of CTC was 43.5 (range: 0–4036) in CVB and 33 (range: 0–4013) in PVB (P=0.001). The CTC counts in CVB and PVB were strongly correlated (R2=0.952, P<0.001). Both CTC counts in CVB and PVB were correlated with levels of CA15.3 (R2CVB=0.498, P=0.005; R2PVB=0.509, P=0.004). Except for a higher number of CTC in CVB in the presence of bone metastasis (P=0.044), no correlations between the number of CTC in either CVB or PVB and specific sites of metastatic involvement were observed.

Using the five CTC per 7.5 ml prognostic cutoff previously described (Cristofanilli et al, 2004) to discriminate between CTC positive (⩾5 CTC per 7.5 ml) and CTC negative (<5 CTC per 7.5 ml) MBC patients, 22 out of 30 (73%) patients were CTC positive for both CVB and PVB. There was a 100% concordance between the results of the CVB and PVB (Table 2).

Comparison of CTC distribution patterns

We subsequently divided the 26 patients with detectable CTC in three distinct groups based on the difference in CTC counts between paired CVB and PVB samples, calculated as the mathematical difference of both counts divided by their mean. A threshold of 15% was applied to define a significant difference based on coefficients of variation for different sources of analytical variability of the CellSearch System reported in literature (Allard et al, 2004; Riethdorf et al, 2007; Kraan et al, 2011). Because of statistical considerations, patients with less than five CTC per 7.5 ml in both CVB and PVB were considered to have equal counts in both compartments. Using these criteria 12 out of 26 patients (46%) patients had significantly higher CTC counts in CVB than in PVB with a median percentage of difference of 59% (range: 26–108%) whereas in only two (8%) patients higher numbers were observed in PVB with a median percentage of difference of 50% (range: 18–82%). In the remaining 12 (46%) patients no difference was observed between both counts (Table 2). No correlation was found between the pattern of CTC distribution in CVB and PVB and specific sites of metastasis in general or the prevalence of clinically evident lung metastases in particular.

Comparison of CTC characteristics at different vascular compartments

We compared the size of the CTC at different vascular compartments. CTC were measured on screen in two dimensions and size was estimated based on the geometrical area of an ellipse as shown in Figure 2. Mean size of CTC in CVB and PVB of the same patient was compared only in those patients with at least five measurable CTC in both compartments. Overall, mean CTC area measured 77.59±4.68 μm2 in CVB and 62.28±5.02 μm2 in PVB, respectively (P<0.001). When analysing samples pairwise, CTC measured in CVB were significantly larger than CTC measured in PVB in 11 out of 22 patients (50%). In the other 11 patients no statistically significant difference in average CTC size between CVB and PVB was observed. Furthermore, we calculated a score to estimate the contribution of size to the numerical difference in CTC counts between CVB and PVB as demonstrated in Figure 2B and C. When applying a cutoff for CTC size in CVB at the maximal CTC size measured in PVB, on average 19% (range: 0–48%) of the numerical difference in CTC counts between CVB and PVB could be explained on the basis of size (Table 2; Figure 2C).

Comparison of CTC size in CVB and PVB. (A) Calculation method for the area of an individual CTC as a measure for size. (B) Frequency curves of CTC sizes in CVB and PVB for one illustrative patient. A cutoff for size in CVB was applied at the maximal size measured in PVB. (C) Formula for the calculation of the ‘contribution score’ for size to the numerical difference in CTC between CVB and PVB.

Discussion

In this study, we compared the number of CTC, as assessed by the CellSearch System, in blood samples obtained from different sites throughout the circulation in 30 patients with MBC. We observed significantly higher numbers of CTC in CVB than in PVB in 46% of the patients with detectable CTC. The opposite was true in only 8% of the patients whereas in another 46% of patients no difference was observed at all. Given the fact that all patients included in this study suffered from extensive metastatic involvement, the observation of a steep concentration gradient of CTC in the blood circulation from the central venous compartment towards the peripheral venous compartment is in accordance with the differences in CTC counts between portosystemic and peripheral systemic circulations in patients with liver metastasis from colorectal cancer reported by Jiao et al (2009).

We believe that the findings of the current study have several important clinical and biological implications. First, although it was generally reassuring that a 100% concordance between CVB and PVB was observed when CTC results where dichotomised according to the ⩾5 CTC per 7.5 ml prognostic cutoff, differing CTC counts according to the site of blood collection might be confounding when using decreases or increases in absolute CTC numbers as a surrogate endpoint for the assessment of treatment efficacy in cancer patients as proposed by several authors (Smith et al, 2000; Pachmann et al, 2008; Molife et al, 2011). From this perspective, comparison of CTC levels over the course of treatment would only render reliable information if blood samples were obtained from the same vascular site. This also implies the need of recording the site of blood sampling on every occasion. In addition, as this was only a small study it cannot be excluded that in larger patient series discordant results according to the ⩾5 CTC per 7.5 ml prognostic cutoff will be observed.

Second, the observed difference in CTC numbers between CVB and PVB might also provide direct insight into CTC biology in the human circulation. As most patients included in this study had multiple systemic metastases – draining directly to the CVB compartment – and metastases in the distal arm – draining to the antecubital vein from which the PVB was drawn – were not seen, the observation of higher CTC numbers in the CVB compared with the PVB suggests an important filtering function for the lung microvascular system in these patients. Although this might not apply for CTC shedding from lung metastases, we were not able to show any association between the CTC distribution pattern and the presence or absence of clinically evident lung metastases, probably because almost all patients with lung metastases also suffered from diffuse systemic disease. Only one patient was diagnosed with isolated lung metastases. In this patient one CTC was observed, both in CVB and PVB.

Taking into account that the average cardiac output of a resting adult is ∼5 l per min and assuming that the difference in CTC counts between CVB and PVB is constant over time, one could calculate the total number of CTC filtered by the lungs in 24 h. For instance for patient 1 in Table 2 presenting with 175 CTC per 7.5 ml in CVB and 87 CTC per 7.5 ml in PVB, this would mean that a total of 85 million CTC would be filtered out by the lungs in 1 day's time. The cumulative entrapment of CTC in the microcirculation of the lungs might potentially provide an explanation for some radiologically unexplained respiratory distress syndromes frequently observed in end-stage cancer patients (Roberts et al, 2003). The observation of intravascular tumour cells in microvascular blood samples in patients suggested to suffer from so-called ‘lymphangitic’ carcinomatosis is in keeping with this observation (Masson et al, 1989).

Third, to address the extent to which size filtration might contribute to the observed differences in more depth, we compared the size of CTC visualised by the CellSearch System in CVB and PVB of the same patient. Although in 50% of the patients CTC in CVB were significantly larger than CTC in PVB, these size differences could only explain 0–48% of the difference in CTC counts observed between both compartments.

Last, the lung is a very frequent site of metastatic growth in patients with MBC. Animal models have suggested that a primary intravascular location of breast cancer cells occurs as a mode of intravascular growth before extravasation (Wong et al, 2002). Our observation of a high degree of cancer cell retention in the lung, suggests at least a stochastic advantage for the lung to harbour efficient metastatic growth. Again, this is in keeping with the observations made by Jiao et al (2009) explaining the high propensity of colorectal cancer to seed to the liver and lungs. It must be stressed that these observations are by no means in contradiction with any superimposed selective and organ-specific homing model that, beside size filtration, might also account in part for the loss of (subpopulations) of CTC throughout the circulation (Müller et al, 2001; Glinskii et al, 2005; Nguyen et al, 2009). From this perspective, it will be of interest to compare molecular profiles of CTC harvested at different sites in the blood circulation with regard to cell adhesion pathways, epithelial-mesenchymal transition and stem cell characteristics, which is the subject of an ongoing study.

A limitation of the current study is the variety of lines and types of treatment the included patients previously had received. Rather than representing one cell population, CTC are considered to form a heterogeneous cell population and different treatments might have discrete effects on specific CTC subpopulations (Meng et al, 2004b; Aktas et al, 2009; Van Der Auwera et al, 2010). Also, the fact of most patients suffering from diffuse metastatic disease makes it very difficult to draw firm conclusions on how CTC circulate or rather shed in the blood stream in relation to specific sites of disease involvement. To address these questions properly, larger studies including more uniform, less extensively pretreated patient populations and patients with metastatic disease confined to either the lungs or the systemic circulation, must be carried out.

In conclusion, we observed statistically different numbers of CTC in CVB and PVB in 14 of 26 (54%) patients with MBC. As quantitative assessment of CTC is proposed for the evaluation of treatment efficacy in patients with MBC, registration of the site of blood collection is warranted in clinical practice and studies evaluating the role of CTC assessment to be able to draw correct conclusions.

Change history

29 March 2012

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Aktas B, Tewes M, Fehm T, Hauch S, Kimmig R, Kasimir-Bauer S (2009) Stem cell and epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers are frequently overexpressed in circulating tumor cells of metastatic breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res 11: R46

Allard WJ, Matera J, Miller MC, Repollet M, Connelly MC, Rao C, Tibbe AGJ, Uhr JW, Terstappen LWMM (2004) Tumor cells circulate in the peripheral blood of all major carcinomas but not in healthy subjects or patients with nonmalignant diseases. Clin Cancer Res 10: 6897–6904

Attard G, Swennenhuis JF, Olmos D, Reid AHM, Vickers E, A’hern R, Levink R, Coumans F, Moreira J, Riisnaes R, Oommen NB, Hawche G, Jameson C, Thompson E, Sipkema R, Carden CP, Parker C, Dearnaley D, Kaye SB, Cooper CS, Molina A, Cox ME, Terstappen LWMM, De Bono JS (2009) Characterization of ERG, AR and PTEN gene status in circulating tumor cells from patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Res 69: 2912–2918

Biggers B, Knox S, Grant M, Kuhn J, Nemunatitis J, Fisher T, Lamont J (2009) Circulating tumor cells in patients undergoing surgery for primary breast cancer: preliminary results of a pilot study. Ann Surg Oncol 16: 969–971

Boulpaep EL (2003) The microcirculation. In Medical Physiology. A Cellular and Molecular Approach Boulpaep EL, Boron WF (eds). pp 463–482. Saunders: Philadelphia

Cohen SJ, Punt CJA, Iannotti N, Saidman BH, Sabbath KD, Gabrail NY, Picus J, Morse M, Mitchell E, Miller MC, Doyle GV, Tissing H, Terstappen LWMM, Meropol NJ (2008) Relationship of circulating tumor cells to tumor response, progression-free survival, and overall survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 26: 3213–3221

Cristofanilli M, Budd GT, Ellis MJ, Stopeck A, Matera J, Miller MC, Reuben JM, Doyle GV, Allard WJ, Terstappen LWMM, Hayes DF (2004) Circulating tumor cells, disease progression, and survival in metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med 351: 781–791

de Bono JS, Attard G, Adjei A, Pollak MN, Fong PC, Haluska P, Roberts L, Melvin C, Repollet M, Chianese D, Connely M, Terstappen LWMM, Gualberto A (2007) Potential applications for circulating tumor cells expressing the insulin-like growth factor-I receptor. Clin Cancer Res 13: 3611–3616

De Bono JS, Scher HI, Montgomery RB, Parker C, Miller MC, Tissing H, Doyle GV, Terstappen LWWM, Pienta KJ, Raghavan D (2008) Circulating tumor cells predict survival benefit from treatment in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res 14: 6302–6309

Glinskii OV, Huxley VH, Glinsky GV, Pienta KJ, Raz A, Glinsky VV (2005) Mechanical entrapment is insufficient and intercellular adhesion is essential for metastatic cell arrest in distant organs. Neoplasia 7: 522–527

Goodale D, Phay C, Postenka CO, Keeney M, Allan AL (2009) Characterization of tumor cell dissemination patterns in preclinical models of cancer metastasis using flow cytometry and laser scanning cytometry. Cytometry A 75A: 344–355

Hayes DF, Cristofanilli M, Budd GT, Ellis MJ, Stopeck A, Miller MC, Matera J, Allard WJ, Doyle GV, Terstappen LWWM (2006) Circulating tumor cells at each follow-up time point during therapy of metastatic breast cancer patients predict progression-free and overall survival. Clin Cancer Res 12: 4218–4224

Ignatiadis M, Kallergi G, Ntoulia M, Perraki M, Apostolaki S, Kafousi M, Chlouverakis G, Stathopoulos E, Lianidou E, Georgoulias V, Mavroudis D (2008) prognostic value of the molecular detection of circulating tumor cells using a multimarker reverse transcription-PCR assay for Cytokeratin 19, Mammaglobin A, and HER2 in early breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 14: 2593–2600

Jiao LR, Apostolopoulos C, Jacob J, Szydlo R, Johnson N, Tsim N, Habib NA, Coombes RC, Stebbing J (2009) Unique localization of circulating tumor cells in patients with hepatic metastases. J Clin Oncol 27: 6160–6165

Kraan J, Sleijfer S, Strijbos MH, Ignatiadis M, Peeters D, Pierga J-Y, Farace F, Riethdorf S, Fehm T, Zorzino L, Tibbe AGJ, Maestro M, Gisbert-Criado R, Denton G, de Bono JS, Dive C, Foekens JA, Gratama JW (2011) External quality assurance of circulating tumor cell enumeration using the CellSearch® system: a feasibility study. Cytometry B Clin Cytom 80: 112–118

Krag DN, Ashikaga T, Moss TJ, Kusminsky RE, Feldman S, Carp NZ, Moffat FL, Beitsch PD, Frazier TG, Gaskin TA, Shook JW, Harlow SP, Weaver DL (1999) Breast cancer cells in the blood: a pilot study. Breast J 5: 354–358

Masson RG, Krikorian J, Lukl P, Evans GL, McGrath J (1989) Pulmonary microvascular cytology in the diagnosis of lymphangitic carcinomatosis. N Engl J Med 321: 71–76

Meng S, Tripathy D, Frenkel EP, Shete S, Naftalis EZ, Huth JF, Beitsch PD, Leitch M, Hoover S, Euhus D, Haley B, Morrison L, Fleming TP, Herlyn D, Terstappen LWMM, Fehm T, Tucker TF, Lane N, Wang J, Uhr JW (2004a) Circulating tumor cells in patients with breast cancer dormancy. Clin Cancer Res 10: 8152–8162

Meng S, Tripathy D, Shete S, Ashfaq R, Haley B, Perkins S, Beitsch P, Khan A, Euhus D, Osborne C, Frenkel E, Hoover S, Leitch M, Clifford E, Vitetta E, Morrison L, Herlyn D, Terstappen LWMM, Fleming T, Fehm T, Tucker T, Lane N, Wang J, Uhr J (2004b) HER-2 gene amplification can be acquired as breast cancer progresses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 9393–9398

Molife LR, Fong PC, Paccagnella L, Reid AHM, Shaw HM, Vidal L, Arkenau H-T, Karavasilis V, Yap TA, Olmos D, Spicer J, Postel-Vinay S, Yin D, Lipton A, Demers L, Leitzel K, Gualberto A, de Bono JS (2011) The insulin-like growth factor-I receptor inhibitor figitumumab (CP-751,871) in combination with docetaxel in patients with advanced solid tumours: results of a phase Ib dose-escalation, open-label study. Br J Cancer 103: 332–339

Mostert B, Sleijfer S, Foekens JA, Gratama JW (2009) Circulating tumor cells (CTCs): detection methods and their clinical relevance in breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 35: 463–474

Müller A, Homey B, Soto H, Ge N, Catron D, Buchanan ME, McClanahan T, Murphy E, Yuan W, Wagner SN, Barrera JL, Mohar A, Verástegui E, Zlotnik A (2001) Involvement of chemokine receptors in breast cancer metastasis. Nature 410: 50–56

Nguyen DX, Bos PD, Massagué J (2009) Metastasis: from dissemination to organ-specific colonization. Nat Rev Cancer 9: 274–284

Pachmann K, Camara O, Kavallaris A, Krauspe S, Malarski N, Gajda M, Kroll T, Jörke C, Hammer U, Altendorf-Hofmann A, Rabenstein C, Pachmann U, Runnebaum I, Höffken K (2008) Monitoring the response of circulating epithelial tumor cells to adjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer allows detection of patients at risk of early relapse. J Clin Oncol 26: 1208–1215

Pierga J-Y, Bidard F-C, Mathiot C, Brain E, Delaloge S, Giachetti S, De Cremoux P, Salmon R, Vincent-Salomon A, Marty M (2008) Circulating tumor cell detection predicts early metastatic relapse after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in large operable and locally advanced breast cancer in a phase II randomized trial. Clin Cancer Res 14: 7004–7010

Rack BK, Schindlbeck C, Andergassen U, Schneeweiss A, Zwingers T, Lichtenegger W, Beckmann M, Sommer HL, Pantel K, Janni W, SUCCESS Study Group (2010) Use of circulating tumor cells (CTC) in peripheral blood of breast cancer patients before and after adjuvant chemotherapy to predict risk for relapse: the SUCCESS trial. J Clin Oncol (Meeting Abstr) 28: 1003

Riethdorf S, Fritsche H, Muller V, Rau T, Schindlbeck C, Rack B, Janni W, Coith C, Beck K, Janicke F, Jackson S, Gornet T, Cristofanilli M, Pantel K (2007) Detection of circulating tumor cells in peripheral blood of patients with metastatic breast cancer: a validation study of the cellsearch system. Clin Cancer Res 13: 920–928

Roberts KE, Hamele-Bena D, Saqi A, Stein CA, Cole RP (2003) Pulmonary tumor embolism: a review of the literature. Am J Med 115: 228–232

Sandri MT, Zorzino L, Cassatella MC, Bassi F, Luini A, Casadio C, Botteri E, Rotmensz N, Adamoli L, Nolè F (2010) Changes in circulating tumor cell detection in patients with localized breast cancer before and after surgery. Ann Surg Oncol 17: 1539–1545

Smith BM, Slade MJ, English J, Graham H, Lüchtenborg M, Sinnett HD, Cross NC, Coombes RC (2000) Response of circulating tumor cells to systemic therapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer: comparison of quantitative polymerase chain reaction and immunocytochemical techniques. J Clin Oncol 18: 1432–1439

Tibbe AGJ, Miller MC, Terstappen LWMM (2007) Statistical considerations for enumeration of circulating tumor cells. Cytometry A 71A: 154–162

Van Der Auwera I, Peeters D, Benoy IH, Elst HJ, Van Laere SJ, Prové A, Maes H, Huget P, Van Dam P, Vermeulen PB, Dirix LY (2010) Circulating tumour cell detection: a direct comparison between the CellSearch System, the AdnaTest and CK-19/mammaglobin RT–PCR in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Br J Cancer 102: 276–284

Weiss L (1992) Comments on hematogenous metastatic patterns in humans as revealed by autopsy. Clin Exp Metastasis 10: 191–199

Wong CW, Song C, Grimes MM, Fu W, Dewhirst MW, Muschel RJ, Al-Mehdi A-B (2002) Intravascular location of breast cancer cells after spontaneous metastasis to the lung. Am J Pathol 161: 749–753

Acknowledgements

Dieter Peeters is a research assistant of the Fund for Scientific Research Flanders. We sincerely thank all patients who gave blood samples for research intentions. We acknowledge Christel Verbruggen, Dominique Schroyens and the Clinical Trial Organisation from GZA Hospitals Sint-Augustinus, Antwerp, Belgium for their assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Peeters, D., Van den Eynden, G., van Dam, PJ. et al. Circulating tumour cells in the central and the peripheral venous compartment in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Br J Cancer 104, 1472–1477 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2011.122

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2011.122

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Effects of robot-assisted versus hand-assisted nephroureterectomy on circulating tumor cells for upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Detection of circulating tumor cells and circulating tumor DNA before and after mammographic breast compression in a cohort of breast cancer patients scheduled for neoadjuvant treatment

Breast Cancer Research and Treatment (2019)

-

Phenotype of circulating tumor cell: face-off between epithelial and mesenchymal masks

Tumor Biology (2016)

-

Bone marrow as a reservoir for disseminated tumor cells: a special source for liquid biopsy in cancer patients

BoneKEy Reports (2014)

-

Comparison of circulating tumor cells (CTC) in peripheral blood and disseminated tumor cells in the bone marrow (DTC-BM) of breast cancer patients

Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology (2013)