Key Points

-

Provides information relating to the workload of dental therapists/hygienist-therapists employed in primary care settings.

-

Shows how the employment setting influences the spectrum of work undertaken.

-

Highlights the need to consider new models of care which make best use of DCPs.

Abstract

Aim To determine whether dental therapists/hygienist-therapists employed in UK primary care settings are currently fulfilling a mainly preventive or therapeutic role, and whether the pattern of work they undertake depends upon the specific setting in which they are employed.

Design Self-administered postal questionnaire including a day-book proforma.

Results Useable day-book proformas were received from 209 dental therapists/hygienist-therapists. Their analysis indicated that those working in the GDS (when compared with those working in the CDS) are predominantly treating adults and being delegated a preventive role which could equally be fulfilled by singly-qualified dental hygienists.

Conclusion This study suggests that primary care dentists working with dental therapists/hygienist-therapists are currently utilising only a small range of these professionals' skills. Consideration should be given as to whether to (a) meet the wishes of dentists by training singly-qualified hygienists, or (b) develop a system which encourages dentists to use dental therapists/hygienist-therapists differently.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

General dental service (GDS) workload statistics have repeatedly shown that only a small proportion of treatment provision can be considered 'complex'. In 1991/1992, 25.6 million items of service were completed in the GDS; 44% were a combination of a check-up, diagnosis including a radiograph, and scale and polish while a further 36% were 'routine' fillings and extractions. Only 6% involved complex restorative work such as crowns, inlays, porcelain veneers or bridges. By 1997/98, the proportion of complex treatment provision had fallen while that of simple treatments had increased. Writing in 2001, Harris and Haycox1 concluded that up to 36% of the work undertaken by dentists could be carried out by dental therapists. It is likely that, with the introduction of additional duties in 2002 and the recent introduction of competency-based training, this percentage will by now have increased.

Disappointingly, recent publications have highlighted both ignorance among dentists with regard to the clinical remit and cost-effectiveness of dually-qualified hygienist-therapists1,2 and a degree of negativity towards their employment in general dental practice. In a survey of 616 NHS-registered dentists in South East Scotland,2 while the majority (64%) of respondents stated that they would consider employing a hygienist-therapist, dentists were shown to have a restricted and inaccurate view of the clinical remit of this professional group. In a similar survey of 550 practices in Wales,3 43% of responding principals considered that they were likely to employ a hygienist-therapist in the future. Once more, however, it was observed that respondents demonstrated a clear lack of knowledge in relation to the cost effectiveness of hygienist-therapists, with 39% of principals admitting that this individual would be expected to spend more than half their working time on hygiene treatment.

Given the clinical remit of dually-qualified hygienist-therapists, appropriate use of this professional group is an obvious means of resolving the increasing problem of access to NHS dental care. In recognition of this, 150 additional training places for hygienist-therapists have been funded in England and opportunities for hygienist training reduced. To date, however, there have been no data to show what treatment is actually being delivered by those working as dental therapists/hygienist-therapists in primary dental care settings. This study was designed to determine whether these individuals are currently fulfilling a mainly preventive or therapeutic role, and whether the pattern of work they undertake depends upon the specific setting in which they are employed.

Materials and methods

A self-administered questionnaire was designed for data collection. This instrument was divided into two sections. The first covered demographic characteristics of respondents and included multiple-choice questions about place of employment and nature of registration (ie hygienist and therapist or therapist alone) and the number of sessions worked per week. The second section focused on current working practice: a day-book proforma was designed to collect information on the number and type of patients seen and dental procedures undertaken on four clinical sessions in one week. Data were recorded for all booked appointments; information regarding failed appointments was, therefore, included.

The questionnaire was pilot tested on a sample of dental therapists/hygienist-therapists, following which minor modifications were made to improve wording and clarity. The definition of the term 'session' (ie a full morning or afternoon) was included in the covering letter.

Six hundred and eighty-seven dental therapists/hygienist-therapists were identified as registered with the General Dental Council for 2006.4 Nine individuals with addresses outside the United Kingdom were excluded from the study, leaving a potential study group of 678. Each of these registrants was sent a copy of the questionnaire, accompanied by a covering letter and a postage-paid envelope for its return. In order to allow the identification of non-respondents, each questionnaire was coded, a code-break being kept by a third party not directly involved in the study. Non-respondents were sent a reminder questionnaire two months after the initial mailing.

Data entry and analysis was accomplished using Microsoft Excel software.

Results

Following the first mailing, nine questionnaires were returned unopened and with an indication that the addressee had moved, thus reducing the potential study group to 669 subjects. As a result of the two mailings, a total of 286 completed or partially completed questionnaires were received from these 669 subjects, a response rate of 42.8%. However, a further 87 potential subjects were subsequently excluded from the study; 19 of these (6.6%) were currently employed solely as hygienists, 12 (4.2%) were working in oral health promotion, 12 (4.2%) were employed in dental hospitals, 8 (2.8%) were on maternity/sick leave, 14 (4.9%) were unemployed or not practising, 15 (5.3%) had retired and 7 (2.5%) declined to take part in the study. The following results are, therefore, based on a final sample of 209.

Section 1 – demographic characteristics of respondents

Of the 209 respondents, 175 (83.7%) worked in England, 24 (11.5%) in Wales, 7 (3.4%) in Scotland and 3 (1.4%) in Northern Ireland.

One hundred and forty-eight (70.8%) had been qualified for more than ten years, 29 (13.9%) had been qualified for between five and ten years and 30 (14.4%) had been qualified for less than five years. Two respondents (1.0%) did not answer this question.

One hundred and thirty (62.2%) were registered only as a dental therapist while 77 (36.8%) were registered as both hygienist and therapist. Two (1.0%) respondents did not answer this question.

The dental therapists/hygienist-therapists in this sample worked a mean of 6.9 sessions per week (SD 2.69). One hundred and thirty-three (63.6%) indicated that they were employees while 57 (27.3%) were self employed; 17 (8.1%) were both employees and self employed (ie they had different contracts of employment at different places of work). Two respondents (1.0%) did not answer this question.

The majority of dental therapists/hygienist-therapists (66, 31.6%) stated that they earned between £20,000 and £30,000 per year; 37 (17.7%) earned more than £36,000 per year, 58 (27.8%) earned between £31,000 and £35,000 per year and 42 (20.1%) earned less than £20,000 per year. Six respondents (2.9%) did not answer this question.

Section 2 – current working practices of respondents

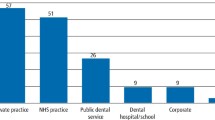

Eighty-two respondents stated that they worked in the community dental service (CDS), 50 worked in personal dental service (PDS) and 109 in the general dental service (GDS). These figures are not mutually unique as some respondents worked in more than one setting.

Activity data were provided for 758 clinical sessions (260 CDS, 153 PDS and 345 GDS). In the CDS, dental therapists/hygienist-therapists saw a mean of 7.45 (SD 2.48) patients per session; in PDS and GDS settings, they saw 8.78 (SD 3.07) and 10.08 (SD 3.39) respectively. Table 1 shows a breakdown (in percentage terms) of (1) attendance by age and (2) failed appointments.

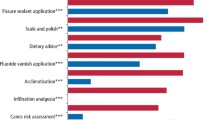

Table 2 shows the contribution (in percentage terms) of specific items of treatment to the total clinical activity in each setting. These items of treatment can be divided into three categories:

-

Preventive – scale and polish, sub-gingival root debridement, topical fluoride application, fissure sealant application and oral hygiene instruction

-

Therapeutic – restorations, extraction of deciduous teeth, deciduous pulp therapy, placement of stainless steel crowns on deciduous teeth and re-cementing of crowns on permanent teeth

-

Other – intra-oral assessment, radiography, provision of infiltration/block anaesthesia, impression taking.

Table 3 illustrates (in percentage terms) the relative contribution of these three categories of intervention to the workload in all three settings.

Discussion

The data for this study were collected by means of a self-administered postal questionnaire. An acknowledged disadvantage of this technique is the level of non-response. The overall response rate experienced here, although disappointing, was therefore to be expected and may reflect the time-consuming nature of the questionnaire.

The geographic distribution of respondents closely correlates to the population levels in the UK.5 The proportion of responding dental therapists/hygienist-therapists (52.1%) currently working in the GDS, however, suggests that there has been a dramatic change since July 2002 when they were first allowed to work in all sectors of the dental profession. Indeed, only seven years ago, Gibbons and co-workers6 found that 93% of dental therapists were employed in the CDS.

The workload undertaken by dental therapists/hygienist-therapists varied according to the specific primary care setting in which they worked: those working in the GDS saw the highest number of patients per session and those in the CDS, the lowest. This may reflect the role of the latter service in providing treatment for children, adults with 'special needs' and other individuals who require additional time to be devoted to their care.

Dental therapists/hygienist-therapists appear to have been assigned different roles within the three primary care settings, being more likely to treat adults in the GDS and children in the CDS. Indeed, on the sessions for which data were provided, 62.4% of patients attending appointments in the CDS were children. In contrast, 88.3% of patients attending appointment in the GDS were adults. The variation in the preventive vs therapeutic balance in the three settings, with dental therapists/hygienist-therapists working in general dental service adopting a predominantly preventive role should, therefore, not be surprising.

While dentists have been reported to have a favourable attitude to an expansion in the employment and training of dental care professionals, hygienists appear to be viewed the most favourably.7 Despite this, the majority of training establishments in the UK have moved from offering single qualifications in dental hygiene and dental therapy, to dual training in hygiene and therapy. If the substantial restorative skills of these individuals are not put to good use in the GDS, not only will the contribution they could potentially make to patient care be seriously affected, the workforce will become de-skilled in this area. This is not a problem restricted to dental care professionals as dentists may equally become de-skilled. This is, however, a potential area of concern in relation to clinical governance.

Conclusion

Because of the small sample size it is not suggested that the results presented here are conclusive. The authors hope, however, that they will stimulate debate on the future role of this category of dental care professional and inform effective workforce planning. Consideration should be given as to whether to a) satisfy the wishes of dentists by training singly-qualified hygienists or b) develop a system which encourages dentists to use dental therapists/hygienist-therapists differently.

References

Harris R V, Haycox A. The role of team dentistry in improving access to dental care in the UK. Br Dent J 2001; 190: 353–356.

Ross M K, Ibbetson R J, Turner S. The acceptability of dually-qualified dental hygienist-therapists to general dental practitioners in South-East Scotland. Br Dent J 2007; 202: E8. doi: 10.1038/bdj.2007.45

Jones G, Devalia R, Hunter L. Attitudes of general dental practitioners in Wales towards employing dental hygienist-therapists. Br Dent J 2007; 203: E19. doi: 10.1038/bdj.2007.890

General Dental Council. Annual Report 2005. London: GDC, 2005. http://www.gdc-uk.org/NR/rdonlyres/CC041FA3-1FA9-405B-A48B-A8C0D9BB21BE/45615/GDCAnnualReport.pdf

National Statistics Online. http://www.statistics.gov.uk

Gibbons D E, Corrigan M, Newton J T. The working practices and job satisfaction of dental therapists: findings of a national survey. Br Dent J 2000; 189: 435–438.

Sprod A, Boyles J. The workforce of professionals complementary to dentistry in the general dental practices in the South West. Br Dent J 2003; 194: 389–397.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jones, G., Evans, C. & Hunter, L. A survey of the workload of dental therapists/hygienist-therapists employed in primary care settings. Br Dent J 204, E5 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/bdj.2007.1205

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bdj.2007.1205

This article is cited by

-

Time to complete contemporary dental procedures – estimates from a cross-sectional survey of the dental team

BMC Oral Health (2023)

-

General dental practices with and without a dental therapist: a survey of appointment activities and patient satisfaction with their care

British Dental Journal (2018)

-

Supporting newly qualified dental therapists into practice: a longitudinal evaluation of a foundation training scheme for dental therapists (TFT)

British Dental Journal (2013)

-

Job satisfaction among dually qualified dental hygienist-therapists in UK primary care: a structural model

British Dental Journal (2011)

-

The policy context for skill mix in the National Health Service in the United Kingdom

British Dental Journal (2011)