Key Points

-

This study suggests that a relatively small proportion of care delivered can be defined as 'complex restorative treatment'.

-

There is considerable potential for delegation of care to dental hygienists and therapists.

-

The findings assume that all the care currently provided is clinically necessary and appropriate.

-

Further work is required on the economic aspects of employing dental hygienists and therapists in general dental practice.

Abstract

This study describes the proportion and volume of work undertaken in primary dental care that could be delegated to hygienists and therapists.

Methods Data on treatment provision, both NHS and private, over one course of treatment for 850 consecutively attending patients at 17 dental practices, selected to be representative of a range of socioeconomic, urban and rural environments, were extracted from case records.

Results The 850 patients attended on 2,433 occasions. Diagnostic examination accounted for 833 (34.2%) visits, while simple, intermediate and complex restorative interventions and other complex interventions accounted for 500 (20.5%), 361 (14.8%), 365 (15%) and 374 (15.4%) visits respectively. The total time required to provide the care was 42,800 minutes, of which 6,550 (15.3%) were devoted to diagnostic examinations, while 10,485 (24.5%), 7,935 (18.5%) and 11,790 (27.5%) were taken up with simple, intermediate and complex restorative care. Other complex interventions accounted for 6,040 (14.2%) minutes. Assuming that dental therapists are permitted to undertake simple and intermediate restorative interventions, they could provide 35.3% of care when number of visits is utilised as the outcome measure, but 43% of the clinical time taken to provide care. Delegation of diagnostic and treatment planning powers to dental therapists could potentially result in 69.5% of visits and 58.3% of clinical time being provided by therapists.

Conclusion These data imply that a considerable proportion of work in UK general dental practice could be delegated to dental hygienists and therapists.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A model of primary dental care, whereby a dentist diagnoses, prescribes and delegates routine clinical care to a team of support professionals, was given prominence in a report by the Nuffield Foundation1 in the early 1990s and subsequently endorsed by a General Dental Council (GDC)2 sponsored review of the use of dental auxiliaries. As a result, the concept of dental care delivered by a multi-skilled team is now well established. In more recent years, legislative, regulatory and policy changes in respect of care provided by dental care professionals (DCPs) have seen significant changes in the range of duties that can be performed by dental hygienists and therapists, in where they are allowed to work and the degree of direct supervision required.3,4,5 As an example, dental therapists, whose practice was previously restricted to the hospital and community dental services, are now free to work in general dental practice.

The most recent consultation document issued by the GDC6 proposes further reform of the role of dental therapists and hygienists. These state that 'permitted duties' as previously laid out in the Dental Auxiliaries Regulations7 will be abolished and replaced by a system of regulation through the training curriculum and ethical guidance. Hence, any expansion in curriculum will allow expansion of clinical duties, subject to GDC approval.

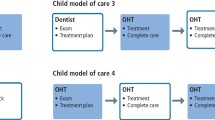

The consultation document further proposes the future expansion of the DCP curriculum to enable direct access to DCPs by patients, stating that they would 'welcome proposals to expand the DCP curricula to enable direct patient access to DCPs'. In such a scenario different options are possible. A patient might have a full mouth assessment by a dentist, or if diagnostic duties are devolved, this might be undertaken by an appropriately trained DCP. Following assessment a patient would receive a treatment plan that they could take to any registered dental professional. The dental professional would then treat the patient within the limits of their competence and make any appropriate referrals. Recall visits could be provided by therapists who would have the option of determining future recall intervals or referring for a full mouth re-assessment with a suitable practitioner.6

Such developments mirror changes in medical care in the UK where the last decade has seen significant delegation of duties previously performed by doctors to nurse practitioners. However, despite these developments, a fundamental question remains unanswered – what is the potential for delegation of clinical care to dental hygienists and therapists in general dental practice? Harris and Haycox8 have pointed out that in contrast to what has happened in primary medical care, there exists a paucity of evidence on which to base future development of the primary care team in dentistry.

Aim

The aim of this study was therefore to determine the potential for delegation of clinical care to dental hygienists and therapists in general dental practice.

Method

The study design comprised a cross-sectional study of care provision to adult patients attending general dental practitioners.

Sample selection

Selection of subjects for the study occurred in two stages.

Selection of practices

Firstly a purposive sample of general dental practices in South Wales, selected to be representative of 'high' and 'low' socio-economic areas and of urban and rural environments, were identified. High and low socioeconomic status (SES) was defined as within the upper and lower quartiles of the Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation,9 an index based on variables derived from the national census. Practices were invited to participate via an initial letter outlining the objectives of the study, followed by a telephone call two weeks later.

Selection of patients

Dentists agreeing to participate in the study were asked to recruit 50 consecutively attending adult patients and seek their consent to participation in the study. The study was restricted to those aged 19 years and above. Patients declining to participate were substituted with subsequent attendees until 50 patients at each practice were recruited. In multiple handed practices, only patients under the care of one dentist were invited to participate in the study.

Data collection

Data on treatment provision was recorded from patient case records by one of the authors (CE). Individual practices were visited and anonymised data on treatment provision for each patient were collected using a specifically designed data collection form. For the most recently completed course of treatment,* details of all clinical procedures were recorded. Individual items of treatment undertaken were categorised according to complexity as per the criteria outlined in Table 1. Treatment items were classified according to the Statement of Dental Remuneration published by the Dental Practice Board (DPB). The DPB were (at the time of the start of the study) responsible for the payment of work undertaken by the dentist, based on a fee per item payment. All treatment was recorded irrespective of whether it was provided via the National Health Service (NHS) or independently. The total number of visits required to complete the treatment was also recorded, as was the clinical time taken for each procedure and demographic data on age, sex and residential postcode of the patient. The time taken for each procedure was determined from the day book in individual practices.

In addition, practice-specific data including postcode and proportion of work undertaken on behalf of the NHS were recorded.

Data analysis

Data forms were coded and the data entered on SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences v11) (SPSS, Illn). Frequencies were used to describe sample demographics and differences between samples were analysed by t-tests. Data were modelled to identify the potential for delegation of clinical care under current and proposed future regulations for the practice of dental therapists and hygienists.

Ethics

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the South East Wales research ethics committee.

Results

Participating practices

In total 17 practices were recruited to the study, nine from high SES areas and eight from low SES areas. Eight practices were in rural areas while nine were urban. Of the recruited practices, four were single-handed, seven were two operator practices and the maximum number of dentists in one practice was five. Commitment to the NHS varied between practices; almost one in four of the dentists were seeing 25% or less of their patients under NHS regulations. A significant difference (p = 0.001) of 8.2% points was observed between the percentage of NHS patients at practices in high and low SES areas. The number of patients registered varied between the different practices and was related to the number of dentists employed. Patient registrations ranged from 1,000 to 5,500 per practice, with a mean of 1,351 patients per dentist.

Participating patients

In total 850 patients were recruited to the study. The mean age of study participants was 49.3 years (range 19-90 years), the modal age cohort being 41-50 years. Females compromised 57.9% of the study sample. NHS care was received by 721 (84.8%) of the study sample – of whom 172 were exempt from patient charges. Of the 15.2% who received care through a private contract, 45 did so through insurance schemes with 84 paying directly.

Clinical treatment profile

Patient visits

To complete their course of treatment, the 850 study participants made 2,433 separate visits to the practices. The frequency of visits ranged from 1 to 14, the mean number of visits per course of treatment being 2.86. The number of visits per treatment category (defined in Table 1), are reported in Table 2. Just over one third of visits were categorised as for examination, and a further fifth were for low technology treatments – mainly scale and polish. Such treatments were received by 490 patients, either at the same visit as their initial examination, or during a further visit (Table 3). While 80 (16.3%) patients receiving low technology treatment did so at their initial visit, the majority of patients attended the practice on a further occasion for this treatment, 339 (69.2%) receiving low technology treatment incurring one additional visit.

A similar analysis of medium technology treatments (simple fillings) shows that of the 313 patients receiving these treatments, 9.3% did so at the same visit as their initial consultation.

Clinical time

The treatment took in total, 42,800 minutes (Table 2). The mean time spent per course of treatment was 50.4 minutes, with 74.7% of patients completing their course of treatment in 60 minutes or less. In 140 cases, the course of treatment lasted just 20 minutes.

Overall, 15.3% of the total time taken was devoted to examinations. While complex restorative treatment accounted for just 15% of visits, it accounted for 27.5% of clinical time.

Potential for delegation of clinical care

The potential for delegation of care to DCPs is shown in Figure 1. Under current legislation, 35.3% of patient visits and 43% of clinical time is devoted to duties that may be undertaken by dental hygienists and therapists. If diagnostic powers were to be granted to dental therapists, then these data suggest that up to 69.5% of visits and 58.4% of clinical time could be delegated.

The number of patients who received low or medium technology treatment, in conjunction with their initial examination visit or over x additional visits, is shown in Table 3. From this it is apparent that of those patients who received low technology treatments (essentially scale and polishes), just 80/490 (16.3%) did so at a single visit. In those patients requiring medium technology treatments (simple fillings), only 29/313 (9.3%) did so at their initial visit. This means that when patients required treatment in addition to a simple examination, in the great majority of cases this entailed at least one further visit to the surgery. Also apparent from the data in Table 3 is the fact that of the patients receiving periodontal therapy, just 0.6% did so over a series of visits that entailed four or more visits, the majority (69.2%) having a scale and polish on one occasion, but separate from the visits on which an examination occurred.

Influence of socio-economic status and practice location

The mean number of visits per course of treatment was slightly higher in rural practices (2.96) than urban practices (2.75). Similarly those located in areas of lower socioeconomic circumstances showed a small increase (2.96) compared to those in deprived areas (2.78) but the differences were not statistically significant in either case.

Discussion

This study was made necessary by the lack of good evidence on the potential for delegation of clinical care in general dental practice. By including a representative sample of dental practices from a diverse range of backgrounds and by including regularly attending patients who were treated both within the NHS and independently, this study provides a unique overview of the care being provided to regularly attending adults in 2005. Details of the time taken by the dentists in each practice to complete each treatment item were derived from day books in each practice. While the timings will not be completely accurate, they do provide a realistic estimate of the time taken, as each practitioner decides the time requirement based upon their own experiences. This approach allowed individual variations to be reflected without the need for practitioners to make individual time recordings for 50 consecutive patients.

The question arises however, as to how representative the patients in this study were of attending adults as a whole. That a greater number of patients were female is in accord with the 1998 adult dental health survey,10 which showed that women attend more regularly than men. In this study 84.8% of patients received their care via the NHS. A June 2006 omnibus survey of a representative sample of adults in South East Wales suggested that 21% of adults received their care independent of the NHS.11 This suggests that the patient sample was reasonably representative of care being provided in South Wales. Data collection occurred prior to the introduction of the New Contract* and none of the practices were operating under personal dental service.** Therefore the practices can be considered to have been providing care under the traditional model that operated in the UK until early 2006.

The study suggests that irrespective of use of number of visits or the time taken to provide clinical care, much of the care being provided in general dental practice to routinely attending patients is either examinations or the provision of scale and polishing or simple restorations. At face value, the potential for delegation in this cohort of patients is high, about one third of visits under current regulations and even greater if dental therapists were permitted to undertake recall examinations and set recall intervals. Any expansion of the roles of DCP duties must be matched by expansion of the DCP curricula, and a considerable addition to existing curricula would be required to allow diagnosis and treatment planning in adult patients.

There are, however, a number of factors that merit further consideration. Firstly the question arises as to the nature of the care that is being provided. The high number of scale and polishes routinely undertaken in general dental practice has previously received adverse comment by the Audit Commission.12 This activity accounted for one fifth of clinical activity, measured either as number of visits or proportion of clinical time. It is, however, apparent that very few patients, less than 1%, underwent an extended course of periodontal therapy. This is in accordance with a previous study of periodontal care in general practice which showed that the number of patients receiving a protracted course of hygiene phase therapy was low, and less than what might be expected given that 10-15% of the UK population are in an at-risk group for significant attachment loss.13,14

It is also apparent that a significant proportion of visits were taken up with clinical examinations. No data were gathered on the time since the patients' last dental visit or on their 'risk status' and so it is not possible to determine if patient attendance patterns would comply with NICE guidelines on recalled attendance.15 If some patients were attending more frequently than was clinically necessary then there would be potential to reduce this element of the care profile.

Turning to the provision of more complex care, this study suggests that at present, just 57% of clinical time is used to provide care that is outwith the remit of a dental hygienist or therapist. The Nuffield report1 envisaged a future whereby a team approach would free dentist time to concentrate on more complex aspects of care. However, in this cohort of patients, just 27.5% of clinical time was devoted to complex restorative care.

A potential disadvantage of increased delegation of clinical care to a dental hygienist or therapist from a patient's perspective is of course the need for an additional visit, with the attendant issues of cost and inconvenience involved. The data presented in Table 3 suggest that in this cohort of patients, of those requiring low and medium technology treatments, just 16.3% and 9.3% had the treatment at the same visit as their initial examination.

Whether using DCPs to provide a greater proportion of care is cost-effective from the perspective of running a dental practice is of course a different matter, and not possible to answer from this study. Harris and Burnside,16 in a study involving the deployment of dental therapists in a personal dental service pilot, concluded that the gross fees and patient charges raised by a dental hygienist failed to cover the cost of the salary of the therapist, dental nurse and practice overheads. Holt,17 however, subsequently pointed out that their research showed that the fee scale did not reflect the true costs or values of treating some patient groups, rather than that therapists were not cost-effective. Galloway et al.18 in a systematic view concluded that there was evidence to show that DCPs were able to diagnose and treat a wide range of oral conditions as well as dentists, but recommended further research to determine their cost-effectiveness and in particular the most effective DCP to dentist ratio.

The potential for delegation suggested in this study has been considered purely from the perspective of the nature of care provided, the time taken to provide the care and the number of visits involved. It has not considered whether or not surgery space is available for DCPs to actually undertake this care. Whether such delegation would be cost-effective or efficient cannot be determined from a study such as this. In addition, the impact of the new NHS dental contract may make the employment of DCPs in general practice less attractive. A future prospective study which examines factors such as the time taken to provide care, accounting for the true costs of four-handed dentistry, and the quality of care provided by DCPs in a general practice setting requires investigation.

Finally, the perceptions of patients of being treated by DCPs, both within the NHS and independently, is at this time a further imponderable in the equation, as to an extent is the view of practitioners on the greater use of DCPs. A 2002 study by Gallagher and Wright19 suggested that dentists had mixed views on the greater use of dental therapists in general dental practice.

Conclusions

This study suggests that there is considerable scope for delegation of care currently being provided in general dental practice to dental therapists and hygienists. Further work is required to determine the feasibility of such delegation from economic and other perspectives and to further develop the true potential of team-based dental care.

References

Nuffield Foundation. Education and training of personnel auxiliary to dentistry. London: Nuffield Foundation, 1993.

General Dental Council. Dental auxiliaries review group. Report on the future of professionals complementary to dentistry. London: General Dental Council, 1998.

Department of Health. Modernising NHS dentistry: implementing the NHS plan. London: Department of Health, 2000.

Department of Health. NHS dentistry: options for change. London: Department of Health, 2002.

The United Kingdom Parliament. The Dental Auxiliaries (Amendment) Regulations 2002. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 2002.

General Dental Council. DCP registration draft rules consultation. London: General Dental Council, 2006. Available at http://www.gdc-uk.org

The United Kingdom Parliament. The Dental Auxiliaries Regulations 1986. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1986.

Harris R V, Haycox A . The role of team dentistry in improving access to dental care in the UK. Br Dent J 2001; 190: 353–356.

Welsh Assembly Government Statistical Directorate. Welsh index of multiple deprivation 2005. Cardiff: Welsh Assembly Government, 2005. Available at http://www.lgdu-wales.gov.uk/eng/WimdProject.asp?id=1758

Office for National Statistics. Adult dental health survey: oral health in the United Kingdom 1998. London: Office for National Statistics, 2000.

Beaufort Research. Wales omnibus survey, June 2006. Cardiff: Beaufort Research, 2006.

Audit Commission. Primary dental care services in England and Wales. London: Audit Commission, 2002.

Chestnutt I G, Kinane D F . Factors influencing the diagnosis and management of periodontal disease by general dental practitioners. Br Dent J 1997; 183: 319–324.

Jenkins W M M, Kinane D F . The “high risk” group in periodontitis. Br Dent J 1989; 167: 168–171.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Dental recall: recall interval between routine dental examinations. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2004.

Harris R, Burnside G . The role of dental therapists working in four personal dental service pilots: type of patients seen, work undertaken and cost-effectiveness within the context of the dental practice. Br Dent J 2004; 197: 491–496.

Holt R D . Cost-effectiveness study of therapists in general practice (comment on Harris and Burnside). Br Dent J 2004; 197: 477.

Galloway J, Gorham J, Lambert M et al. The professionals complementary to dentistry: systematic review and synthesis. Oxford: Centre for Evidence Based Dentistry, 2002.

Gallagher J L, Wright D A . General dental practitioners' knowledge of and attitudes towards the employment of dental therapists in general practice. Br Dent J 2003; 194: 37–41.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Evans, C., Chestnutt, I. & Chadwick, B. The potential for delegation of clinical care in general dental practice. Br Dent J 203, 695–699 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/bdj.2007.1111

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bdj.2007.1111

This article is cited by

-

Advancing Dental Care - Utilising the dental therapist workforce to optimise patient outcomes

BDJ Team (2022)

-

The perceptions and attitudes of qualified dental therapists towards a diagnostic role in the provision of paediatric dental care

British Dental Journal (2022)

-

Needs-led human resource planning for Sierra Leone in support of oral health

Human Resources for Health (2021)

-

The dental therapist's role in a 'shared care' approach to optimise clinical outcomes

BDJ Team (2021)

-

The dental therapist's role in a 'shared care' approach to optimise clinical outcomes

British Dental Journal (2021)