Abstract

The Ras/Raf/MEK/extracellular signal regulated kinase (ERK) (Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK)) signal transduction pathway is a crucial mediator of many fundamental biological processes, including cellular proliferation, survival, angiogenesis and migration. Aberrant signalling through the Ras/MAPK cascade is common in a wide array of malignancies, including multiple myeloma (MM), making it an appealing candidate for the development of novel targeted therapies. In this review, we explore our current understanding of the Ras/MAPK pathway and its role in MM. Additionally, we summarise the current status of small molecule inhibitors of MEK under clinical evaluation, and discuss future approaches required to optimise their use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) are a family of ubiquitously expressed serine/threonine kinases that transmit diverse cell surface signals throughout the cell. MAPK pathways consist of a three-tiered signalling module activated via a phosphorylation cascade. The most proximal kinase in these pathways, the MAPK kinase kinase (MAPKKK or MAP3k), engaged by extracellular signals, phosphorylates a dual specificity MAPK kinase (MAPKK or MAP2K), which in turn phosphorylates and actives the distil effector MAPK. Mammalian MAPK pathways are represented by the Extracellular Signal Regulated Kinase (ERK), c-Jun N-terminal kinase, p38, ERK 5, ERK 3/4 and ERK 7/8 pathways.1

The Ras/MAPK pathway is the best characterised of the mammalian MAPK signal transduction networks, consisting of the Ras proteins, a family of small G-coupled molecules, the Raf kinases (MAP3K), the MAP2K kinases (MEK1 and MEK2) and the pathway distil kinases ERK1 and ERK2. The Ras/MAPK network is frequently deregulated in malignancy and contributes to many of the hallmarks of oncogenesis, including abnormal cellular proliferation, impaired apoptosis, enhanced angiogenesis, metastasis and the development of drug resistance.2 MEK lies at a critical juncture within the Ras/MAPK pathway, having a limited number of direct upstream MAP3K activators and ERK1/2 as its only known cellular targets, thereby making it an attractive target for cancer therapy. Several MEK inhibitors have been developed and investigated in preclinical and clinical models. Results from these studies have been promising and suggest that MEK inhibitors, whether alone or in combination with other anticancer therapies, may have a significant role to play in the future management of malignancy.

Current management strategies for multiple myeloma (MM) involve conventional chemotherapeutics and novel anti-MM agents (thalidomide, lenalidomide and bortezomib), with or without subsequent autologous stem cell transplantation.3 Although these anticancer therapies are typically effective initially, MM remains a fatal and largely incurable disease. This is due to the high frequency of relapse and the eventual development of drug resistance. Accumulative genetic changes within malignant plasma cells, together with MM interplay with the bone marrow microenvironment (BMME), potentiate disease progression by promoting the deregulation of multiple signal transduction networks, one of which is the Ras/MAPK pathway.4, 5 This suggests that MM patients may benefit from the abrogation of this kinase network through the administration of a MEK inhibitor. Here, we discuss the Ras/MAPK pathway, its involvement in MM and the role of MEK inhibitors in the future management of the disease.

Overview of the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway

Members of the Ras protein subfamily (H-, K- and N-Ras) function as molecular switches in cellular signal transduction. Diverse growth factor, mitogen and cytokine engagement of cognate receptors leads to the recruitment of the GDP/GTP exchange factors, growth-factor-receptor bound protein 2 (Grp2) and Sons of Sevenless (SOS) to the plasma membrane where Ras resides. The grp2/SOS complex then promotes inactive Ras to exchange GDP with GTP and enters an activated state.6 Activated Ras then recruits Raf to the cell membrane, where it is activated by phosphorylation. This process is antagonised by GTPase-activating proteins, which promote GTP hydrolysis and the formation of inactive Ras-GDP complexes.7 Approximately 30% of malignancies contain activating mutations in a Ras proto-oncogene, with pancreatic (90%), colon (50%) and thyroid (50%) carcinomas demonstrating the highest prevalence. Mutations typically affect K-Ras and N-Ras, but rarely H-Ras, and occur in a mutually exclusive manner.8

The Raf family of serine/threonine kinases (A-, B- and c-Raf (Raf-1)) lie at the apex of the MEK/ERK pathway. All three Raf isoforms share similar structural characteristics. However, they differ in their ability to phosphorylate and activate MEK, with B-Raf demonstrating higher basal kinase activity compared with Raf-1 and A-Raf.9, 10 Activating B-Raf mutations have been described in 66% of melanomas and to a lesser degree in other solid tumours.11 The clinical relevance of this association is reinforced by the exquisite sensitivity of these B-Raf mutated tumours to MEK inhibition.12 Despite a high prevalence of activating B-Raf mutations in melanoma and solid tumours, these mutations are infrequent in MM.13 This suggests that molecules other than B-Raf or alternative kinase pathways may have a crucial role in MM tumourigenesis.

MEK is a unique dual specificity kinase that phosphorylates both serine/threonine and tyrosine residues.14 MEK consists of two isoforms, MEK1 and MEK2, which in turn phosphorylate ERK1 and ERK2.15 Activated ERK1/2 control a diverse range of cellular processes through their many substrates (>160) that are located in cellular membranes, the cytoplasm and nucleus. Many of these are transcription factors that are important in cellular proliferation, differentiation, survival, angiogenesis and migration.16

Physiological activation of the Ras/MAPK pathway is also influenced by multiple mechanisms. Inhibitory molecules, such as Sprouty proteins (SPRY) and MAPK phosphatases (MKP or DUSPs), engage the pathway at different points to negatively regulate signalling.17, 18 Activated ERK induces the expression of these inhibitory factors. For example, certain DUSPs, induced by ERK-regulated transcription factors, dephosphorylate ERK.19 Downstream signalling from B-Raf, Raf-1 and MEK1 may also be diminished following ERK-mediated phosphorylation.20, 21 These various mechanisms fine tune the activity of the Ras/MAPK cascade through the creation of a negative-feedback loop. As will be discussed later, this mode of regulation has implications for inhibitors targeting the pathway.

The Ras/MAPK pathway and MM

The genetic changes associated with MM are complex and heterogeneous. Increasing evidence suggests that the disease evolves through a multistep transformation process, involving the gain or loss of whole chromosomes, nonrandom chromosomal translocations involving the IgH locus and point mutations.4 These aberrations, which influence the clinical and pathological features of MM are manifest in variable disease progression and therapeutic outcomes.

Several of these molecular alterations lead to deregulated activation of the Ras/MAPK pathway. The t(4;14) translocation that juxtaposes the fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 gene and a strong IgH enhancer, resulting in fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 overexpression, stimulates the Ras/MAPK pathway, an outcome typically associated with abnormal cellular proliferation and apoptosis.22 Activating Ras mutations, which have a reported incidence varying between 32–50% in MM, are also thought to deregulate this pathway.23, 24, 25 K-Ras and N- Ras are the most frequently mutated, with oncogenic H-Ras being a rare phenomenon.25

While certain genetic lesions common to MM (for example, t(14;16), t(4;14) and hyperdiploidy) are also present in the asymptomatic precursor to MM, monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance,26 Ras mutations occur almost exclusively in MM. This indicates that Ras mutations are likely to contribute to the transition of the disease from a premalignant state.27 In the case of the t(4:14) lesion that can activate the Ras/MAPK pathway, this raises the interesting possibility that deregulation of the Ras/MAPK pathway in monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance precedes constitutive MAPK activation associated with Ras mutations. Patients with MM harbouring oncogenic K-Ras often have a worse clinical outcomes compared with those with N-Ras mutations or wild-type Ras 24 This link is exemplified by Ras mutations being associated with the evolution of MM from an intermedullary disease to a more advanced extramedullary phenotype.28 These observations suggest that aberrant MEK/ERK signalling has an important role in MM disease progression and prognosis.

Malignant plasma cell and BMME interactions are thought to contribute to disease progression through the induction of various cytokines and growth factors, a number of which mediate their effects through the Ras/MAPK cascade.5, 29, 30 In addition to a number of these cytokines being able to activate MEK/ERK via the classical Ras/Raf link, another MAP3K, Tpl2 (Cot, MAP3K8), a known oncogene, has emerged as being important in the cytokine-induced activation of ERK in various cell types, in particular hemopoietic cells.31 The observation that the tumour necrosis factor receptor superfamily cytokines (tumour necrosis factor-α, BAFF), CD40 and RANK ligands, all of which have been implicate in MM, activate MEK/ERK via Tpl2 raises the likelihood that the MEK/ERK arm of this MAPK pathway can be activated through different MAP3K.32 With aberrant MEK/ERK signalling thought to be important in regulating the growth, survival, migration and drug resistance of MM, it will be interesting to determine if specific MAP3Ks differentially control these particular features of the disease.

Interactions between Bcl-2-like prosurvival and BH3-only pro-apoptotic family members play an integral role in controlling the balance between cell survival and death though the intrinsic apoptosis pathway. Aberrant expression of these apoptotic regulatory molecules in diverse cancers, including MM, contributes to drug resistance. Importantly, the activity of a number of these proteins is modulated by MEK/ERK signalling. For example, ERK-mediated phosphorylation of the antiapoptotic molecule, Mcl-1, decreases its degradation, thereby promoting cell survival.33 With the overexpression of Mcl-1, a common feature of MM associated with greater relapse and shorter survival,34 constitutive MEK/ERK activity almost certainly contributes to elevated Mcl-1 expression in those MM with lesions in the Ras/ERK pathway. In contrast, Bim, a proapoptotic Bcl-2 family member that can bind to and neutralize Mcl-1, is targeted by ERK phosphorylation for proteasome-dependent degradation.35 Hence, constitutive ERK signalling is likely to contribute significantly to MM survival by stabilising Mcl-1 and diminishing Bim expression. The activity of other prosurvival (Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL) and proapoptotic (Bad) Bcl-2-like proteins, that are also known to be regulated by ERK signalling, represent additional candidates that may contribute to the enhanced survival of MM cells.

MEK inhibitors

MEK1 and MEK2 are homologous dual specificity kinases that share ERK as their only known catalytic substrate,15 making MEK an appealing target for cancer drug development. Although many kinase inhibitors target the ATP-binding region of an enzyme, MEK contains a hydrophobic allosteric pocket adjacent to the ATP-binding site that is not shared with other kinases.36 This offers the opportunity to design highly selective inhibitors of MEK that do not simply target the conserved ATP region of the kinase. In the remainder of the review, we describe some of the various MEK inhibitors currently being investigated and their future role in cancer therapy.

Prototypic MEK inhibitors

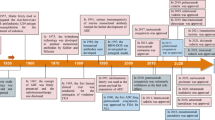

Despite demonstrating in vitro activity, major in vivo limitations were identified for the early first generation MEK inhibitors, PD09805937 and U0126.38 Although both compounds were deemed unsuitable for clinical consideration they have proven to be invaluable tools for investigating the Ras/MAPK pathway. CI-1040 (PD184352) was the first MEK inhibitor to demonstrate tumour inhibitory activity in vivo.39 Encouraging phase I results in advanced cancer patients, where one patient with pancreatic cancer achieved a partial response (PR) lasting 12 months, prompted a phase II study of CI-1040 in patients with advanced solid tumours.40 However, in contrast to the phase I trial, no PR was observed.41 As a result of its weak antitumour activity, development of CI-1040 was terminated in favour of the more potent PD0325901.

Compared with CI-1040, PD0325901 demonstrates significantly improved potency in cell-based assays (100-fold), oral bioavailability and metabolic stability.42 Phase I investigation of PD0325901 was conducted in 66 advanced cancer patients. Three of 48 evaluable patients with melanoma achieved PR, while 10 had stable disease (s.d.) for ⩾4 months. A subset of these patients developed retinal vein occlusion.43 A phase II study of PD0325901 was assessed in 34 advanced non-small cell lung carcinoma patients, but was eventually terminated owing to lack of objective responses and increasing concerns about ocular function and neurotoxicity at therapeutic doses.44 Investigation of these treatment-related toxicities was conducted in animal models, where PD0325901 was found to cause retinal vein occlusion in rabbits. This adverse effect was attributed to the abrogation of phosphorylated-ERK (p-ERK) within the brain.45 In light of these observations, development of PD0325901 has been suspended.

MEK inhibitors in development

AZD6244/ARRY-142886 (selumetinib) is a potent MEK inhibitor that has demonstrated significant tumour suppressive activity in a number of preclinical solid tumour models.46, 47, 48 In cell-based enzymatic assays, AZD6244 inhibited purified MEK at an IC50 of 14.1±0.79 nM, with no inhibition observed at 10 μM against 40 other kinases. Cell lines harbouring oncogenic B-Raf and N-Ras mutations displayed enhanced sensitivity to AZD6244, whereas K-Ras mutated tumours showed variable responsiveness.47 In 2004, a total of 57 patients with advanced cancer were treated in a phase I evaluation of AZD6244. The best clinical response achieved was s.d. ⩾ for 5 months in 9 patients, with 2 patients maintaining s.d. for 19 and 22 months. Similar to PD0325901, blurred vision was reported in 7 patients; however, neurotoxicity was not observed.49 Several phase II trials have since examined the effectiveness of AZD6244 in a diverse range of solid tumours.50, 51, 52 In each of these studies, the efficacy and tolerability of AZD6244 was compared with a conventional chemotherapeutic agent. However, even though some objective responses were observed, AZD6244 failed to demonstrate superior clinical responses over established treatment modalities. As a result of these studies there has not been an advocacy for AZD6244 as a monotherapy.

AS703026/MSC1935369 demonstrates IC50 values in the subnanomolar range and potently inhibits tumour growth in vivo.53 Eighty-five advanced cancer patients were recruited for the phase I trial of AS703026. Visual disturbances were reported in a subset of patients, including some cases of serous macular detachment. Tumour shrinkage was witnessed in four melanoma patients, three of whom (all bearing B-Raf mutations) demonstrated PR.54

XL-518/GDC-0973 is a potent, orally bioavailable inhibitor that blocks MEK1 function with an IC50<1 nM in enzymatic assays measuring ERK phosphorylation. Pharmacodynamic studies have demonstrated that a single dose of GDC-0973 inhibits p-ERK in xenograft tumours for up to 48 h. In contrast to PD0325901, p-ERK levels in mouse brain tissue were not significantly suppressed following the administration of GDC-0973, suggesting reduced potential for adverse CNS events.55 A phase I study of GDC-0972 in patients with solid tumour was initiated in 2007. Confirmed PR were witnessed in three melanoma patients, two of which harboured B-Raf V600E mutations. Six patients with prolonged s.d. (⩾5 months) have been observed to date.56

The MEK inhibitor, BAY869766/RDEA119, specifically inhibits MEK1 (IC50=19 nM) and MEK2 (IC50=47 nM) when compared with 205 other kinases. The antitumour effect of BAY8697655 has been established in mouse xenograft models, with potent growth inhibition observed during drug treatment.57 Early data from the BAY8679655 phase I trial demonstrates good drug tolerability, with rash being the most prevalent treatment-related adverse effect. Among the 69 advanced cancer patients enroled in the trial, 10 achieved s.d. with a mean duration of 10 months. Phase II development of BAY867966 is currently being pursued in light of these findings.58

GSK1120212 is a structurally novel allosteric MEK inhibitor with an in vitro IC50 of 0.4±00.1 nM for MEK1 activation by B-Raf and 10±2 nM for p-MEK1 activity. In cell lines harbouring activating Ras or B-Raf mutations, GSK1120212 inhibited cell proliferation at IC50 values <50 nM, but demonstrated decreased activity against those cells with wild-type Ras or wild-type-B-Raf.59 These results are consistent with other MEK inhibitors, where cells with constitutively active Ras/MAPK signalling demonstrate a reliance on these oncogenic pathways, thereby making them hypersensitive to MEK inhibition. In melanoma xenografted mouse models, GSK1120212 administered orally once daily demonstrated an effective t1/2 of 36 h with sustained suppression of p-ERK for >24 h.60 Notably, inhibition of p-ERK was not observed within brain samples. Phase I results of this compound have recently been presented by Gordon et al.61 For 22 patients with B-Raf mutant melanoma, 1 CR and 9 PR were observed. For 22 patients with pancreatic cancer, 1 PR and 9 s.d. were reported. Early data from a phase I/II trial examining GSK1120212 in patients with relapsed/refractory myeloid malignancies harbouring Ras mutations has also recently been reported. Patients were prospectively screened for K- and N-Ras mutations before receiving daily treatment with GSK1120212. Encouraging signs of clinical activity with manageable adverse effects have been observed.62

Enhancing effectiveness with combination therapies

Despite improvements in clinical potency and pharmacokinetics, MEK inhibitors have generally shown limited effectiveness as monotherapeutic agents. Several reasons may account for this observation.

Abrogation of Ras/MAPK signalling appears to be mainly cytostatic, and suggests that an additional therapeutic modality is required to maximise the antitumour effectiveness of MEK inhibitors. In hepatocellular carcinoma xenograft models, AZD6244 in conjunction with doxorubicin demonstrated enhanced growth suppression (76%±7), compared with AZD6244 (52±15%) and doxorubicin (12±9%) alone. This synergy was associated with increased apoptosis.63 Similar effects have been observed with AZD6244 and docetaxel in malignant melanoma,64 and AZD6244 and cytarabine in acute myelogenous leukaemia.65 The mechanism by which these agents cooperate is not entirely clear, but the available evidence suggests that many of these drugs can activate the Ras/MAPK pathway through diverse processes, thereby increasing the effectiveness of MEK inhibitors.66 However, the inhibitory effects of MEK on cell cycle progression may potentially reduce the effectiveness of many standard chemotherapeutic agents in combination therapy, due to the reliance of these agents on killing malignant cells that are rapidly dividing. Therefore, drug scheduling may have a critical role in the optimal utilisation of MEK inhibitors when combined with traditional chemotherapeutic drugs. In this regard, Yu et al.67 have demonstrated that incubating leukaemic cells with paclitaxel before PD98059 exposure significantly increased cell death. In contrast, pretreatment with the MEK inhibitor reduced the susceptibility of cells to paclitaxel-induced apoptosis.

Activating mutations within the Ras/MAPK network also contribute to the mechanisms of resistance to MEK inhibitors. A number of studies have demonstrated that oncogenic amplification of K-Ras and B-Raf confers decreased susceptibility to AZD6244.68, 69 Point mutations within MEK1 may also significantly attenuate the ability of MEK inhibitors to block ERK signalling in B-Raf V600E mutated tumours.70 These oncogenic events result in constitutive ERK pathway activation. In the absence of oncogenic Ras and Raf mutations, other oncogenic events that engage the Ras/MAPK pathway are also likely to stimulate normal feedback mechanisms that may increase the activity of various intermediaries in the Ras/MAPK signalling module, thereby promoting the ongoing activation of ERK kinase signalling.71 For either scenario, the activity of ERK and its target substrates may be maintained at levels that are sufficient to drive key cellular functions even in the presence of a MEK inhibitor. These observations suggest that targeting multiple nodes within the Ras/MAPK network may be a more efficacious clinical strategy than single target therapy.

The contribution of multiple signalling networks to tumorigenesis also accounts for the limited responses seen with MEK inhibitors alone. For example, the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K/Akt/mTOR) and MAPK pathways share Ras as a common upstream effector.72 Consequently, activation of Ras, despite the downregulation of ERK activity by MKPs and SPRYs, could lead to compensatory signalling through this parallel network. Alternatively, oncogenic mutations within the PI3K/Akt axis may enhance MEK/ERK signal transduction. Indeed, dysregulation of the PI3K/Akt pathway has been shown to correlate with the decreased sensitivity to MEK inhibition.73 Predictably targeting both pathways simultaneously has proven effective in several studies. In AZD6244-resistant gastric cancer cell lines, activation of Akt through the EGFR/PI3K/Akt pathway was still observed following MEK inhibition. Blockade of this pathway using the EGFR inhibitor, gefitinib, synergistically enhanced tumour apoptosis in vitro and in vivo.74 Treatment of mutant murine lung cancers with the dual PI3K/mTOR inhibitor, NVP-BEZ235 and AZD6244 produced similar results.75 Recently, preliminary results from a phase I trial evaluating the combined activity of GDC-0973/XL-518 and the Akt inhibitor, GDC-0941, found that in a cohort of 27 advanced solid tumour patients, three patients achieved prolonged s.d. ⩾6 months when treated with both agents.76 Promising clinical activity has also been observed in the phase I trial of GSK1120212 in conjunction with the Akt inhibitor, GSK2141795.77 The number of preclinical and clinical studies investigating dual Ras/MAPK and PI3K/Akt inhibition indicates a growing trend to using these combinations to maximise antitumour response.

Aberrant signalling through additional kinase pathways may also contribute to MEK inhibitor resistance. For example, although non-small cell lung carcinomas carry both K-Ras and PTEN mutations, resistance of these cell lines to AZD6244 coincides with activation of the Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription pathway (JAK/STAT) following MEK inhibition.78 AZD6244 combined with STAT3 inhibition synergistically induced apoptosis in these cells. This effect can be explained by STAT3 suppressing the proapoptotic protein Bim through upregulation of miRNA-17, which antagonises the Bim expression induced by AZD6244.79 Collectively, these results provide a rationale for combining inhibitors of the JAK/STAT pathway and MEK inhibitors to reduce the potential impact of drug resistance. Information about the use of MEK inhibitors and other kinase pathway inhibitors is unknown.

The role of MEK inhibitors in MM

The advent of novel anti-MM agents has improved the management and prognosis of MM. With the immunomodulatory drugs, thalidomide and lenalidomide, and the proteasome inhibitor, bortezomib, able to abrogate the survival advantage created by the BMME, current research has focussed on combining these novel therapies to improve patient outcomes.80 To date, promising results have been obtained in several clinical trials.81, 82 However, despite the clinical success of thalidomide, lenalidomide and bortezomib, a subset of patients do not initially respond to or ultimately become refractory to these agents.83 This emphasises the need for innovative anti-MM therapies.

The impact of AZD6244 has been investigated in MM cells within the BMME.84 This compound specifically abrogated constitutive and cytokine-stimulated ERK phosphorylation and induced cytotoxicity in a panel of human myeloma cell lines (HMCL). Responses to AZD6244 were also witnessed in tumour cells derived from MM patients with advanced disease. These results suggest that AZD6244 is effective at advanced stages of disease, where MM cells are less reliant on the growth factors produced by the BMME. Furthermore, culturing of HMCL and patient-derived samples in the presence of exogenous interleukin-6 or bone marrow stromal cells did not protect against AZD6244-induced apoptosis. Synergistically enhanced cell death was noted in combinations of AZD6244 with conventional (dexamethasone) and novel (bortezomib, lenalidomide, perifisone) anti-MM agents. AZD6244 as a single agent was also examined in an in vivo human plasmocytoma xenograft model and demonstrated prolonged survival when compared with control animals. Breitkreutz et al.85 have also investigated the consequences of AZD6244 administration on osteoclast differentiation, function and cytokine secretion in MM. AZD6244 blocked osteoclast differentiation and bone reabsorption in a dose-dependent manner. Furthermore, critical MM growth factors produced by the BMME, including interleukin-6, BAFF, APRIL and MIP-1α were all significantly reduced following AZD6244 treatment. Taken together, these results indicate that AZD6244 is able to abrogate paracrine signal dependent MM cell survival within the bone marrow niche. Both these studies provide a preclinical rationale for the further evaluation of AZD6244. A phase II trial examining the compound in MM is presently ongoing.

Treatment with AS703026 has also been explored in MM.86 AS703026 inhibits HMCL and cytokine-induced osteoclast differentiation more potently (9- to 10-fold) than AZD6244, with an IC50 ranging from 0.005–2 μM. No discernable relationship between Ras or Raf mutational status and the sensitivity of HMCL to AS703026 was observed. This compound also induced apoptosis in HMCL cultured in the presence of bone marrow stromal cells. Further evaluation of AS703026 in conjunction with conventional (dexamethasone, melphalan) and novel (lenalidomide, bortezomib, perifisone, rapamycin) anti-MM therapies revealed synergistic cytotoxicity against HMCL and patient samples. Lastly, for tumour cells isolated from patients with relapsed/refractory MM treated with AS703026 at concentrations below 200 nM, dose-dependent cytotoxicity was observed for 15 of 18 patient MM samples. In this cohort of MM patient samples, while six and two of the patient samples harboured K-Ras/N-Ras and B-Raf mutations, respectively, the presence or absence of Ras or B-Raf mutations did not correlate with the sensitivity to MEK inhibition by AS703026.

Despite these encouraging findings, outcomes from solid tumour models suggest that combination regimes are required to maximise the effectiveness of MEK inhibitors in MM. AZD6244 and AS703026 have demonstrated improved potency when used in combination with other anti-MM agents.84, 85, 86 The contribution of additional signalling pathways to MM tumorigenesis also offers the opportunity to target MEK in conjunction with the inhibition of these biochemical networks. Chatterjee et al.30 have determined that the combined disruption of the Ras/MAPK and JAK/STAT pathway is required to induce MM apoptosis in the presence of bone marrow stromal cells. Similarly, the contribution PI3K/Akt and nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NFκB) pathway deregulation exerts on MM and drug resistance also makes these pathways attractive targets for co-inhibition with MEK specific agents.5, 29

Several other small molecule inhibitors have also recently emerged as promising therapies in MM. Histone deacetylases (HDAC) represent a family of enzymes that control transcription by modifying histones. Overexpression of HDAC in MM prevents the transcription of various tumour-suppressor genes, which in turn enhances cellular proliferation and represses cell death.87 Inhibition of HDAC activity reverses these outcomes, culminating in the accumulation of acetylated histones that promote the apoptosis of malignant cells.88 Clinical evaluation of the HDAC inhibitors as single agents in relapsed/refractory MM patients has yielded modest response rates.89, 90 Nevertheless, several studies have reported a significant increase in the anti-MM effect of these agents, when used in conjunction with conventional anti-MM chemotherapeutics,91 lenalidomide and bortezomib.92 Combinations of MEK and HDAC inhibitors have been limited to preclinical studies involving chronic myelogenous leukaemia and non-small cell lung carcinoma cell lines, but preliminary results have been promising.93, 94 Heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) is a molecular chaperone that regulates many of the proteins involved in Ras/MAPK, PI3K/Akt, JAK/STAT and NFκB signalling, as well other biochemical pathways that control apoptosis and cell cycle progression.95 Consistent with these properties, inhibition of HSP90 has been shown to disrupt multiple pathways crucial to MM survival.96, 97 While co-treatment of MM cells with a MEK and HSP90 inhibitors might serve as a means of attenuating the feedback mechanisms that promote resistance to MEK inhibitors, the clinical efficacy of these approaches is dependent upon how selective and active these combination regimes are in vivo. In particular, the potential interrupting multiple kinase networks has for increasing the likelihood of adverse effects and drug toxicity is likely to be an important factor in determining the optimal use of these agents.

Predicting patient responses to MEK inhibitors: identification of relevant biomarkers

As all MEK inhibitors tested to date demonstrate potent and selective activity against MEK1/2, toxicity profiles and drug exposure are likely to be the key criteria that refine these drugs for therapeutic use. Furthermore, it has become clear that certain genetic sub-types in solid tumours are associated with increased susceptibility or resistance to MEK inhibitors. This observation highlights the need for a reliable marker of responsiveness to MEK inhibitors, allowing tailoring of individualised therapies and reducing the occurrence of adverse events.

Currently it remains difficult to determine which patients will benefit most from MEK inhibitor treatment. Whilst activating B-Raf mutations are associated with exquisite sensitivity against these agents, other biochemical markers demonstrate less predictability. For example, the poor correlation between MEK inhibitor susceptibility Ras genotypes and p-ERK expression is well documented.12, 41, 46, 47, 48, 60 In one study, analysis of transcriptional pathway signatures in various solid tumours, identified a panel of 18 genes, the expression of which correlated with responsiveness to AZD6244.98 This signature contained transcriptional targets of ERK involved in negative-feedback regulation (DUSP4/6 and SPRY2), members of the Ets family of transcription factors (ETV4, ETV5 and ELF1) and other genes associated with MAPK signalling, cell cycle progression and tumour prognosis. A 13-gene signature was also identified that was predictive of resistance to AZD6244. This diverse set of genes shared common links with transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), tumour necrosis factor-α and NFκB signalling. The role of these genes in MM and their potential predictive value for MEK inhibitor responsiveness has not been appraised.

Recent data published by Annuziata et al.99 has reported the use of the musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma (MAF) oncogene as a potential biomarker for MEK inhibitor responses in MM. In approximately 10% of cases, aberrant MAF expression is due to a (14;16) translocation. High levels of MAF were also observed in patient samples with t(4;14) translocations. Both t(4:16) and t(4;14) translocations correlate with disease progression and worse overall survival. The MEK/ERK pathway was found to regulate transcription of the MAF proto-oncogene through ERK activation of FOS, a finding consistent with MAF protein and mRNA levels being downregulated following MEK inhibition. To examine the dependence of MM cells on MEK/ERK signalling, U0126 was administered to 16 HMCL that represented the heterogeneous onco-genetics of the disease. Of the 10 HMCL killed by this MEK inhibitor in a dose-dependent manner, 9 cell lines exhibited a t(4;16) or t(4;14) translocation and over expressed MAF. Moreover, the cytotoxic effect of U0126 was not neutralised by the presence of bone marrow stromal cells and remarkably, the impact of MEK inhibition on MM viability could be rescued by exogenous MAF expression. Importantly, this study provides a mechanistic rationale for using MEK inhibitor therapy in MM patients that overexpress c-MAF. These findings emphasise the potential benefit of genetic profiling to identify patients with MAF-expressing MM who may benefit from this class of agents. As part of the phase II trial of AZD6244 in relapsed/refractory MM, extensive molecular profiling of a subset of patients was conducted to correlate the genetic characteristics of MM with clinical outcomes. To date, detailed clinical data from eight patients has been analysed, four of whom overexpress c-MAF or MAF-B. One patient (fibroblast growth factor receptor 3) had a very good PR lasting 8 months. Another patient (MAF-B) had a PR of 6 months. Finally, two patients (one MAF-B, one pending results) demonstrated s.d. of >5 and 13 months, respectively.100 Additional studies with larger sample sizes are required to support or refute MAF expression as a reliable biomarker for MEK inhibition.

Conclusion

The Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway has an established role in the various neoplastic phenotypes observed in many malignancies. Deregulation of this pathway is also a common feature of MM, and contributes to the relapsing and refractory nature of the disease. These observations make this pathway an attractive target for pharmaceutical investigation, with a number of MEK inhibitors having been developed and evaluated clinically. Although preclinical studies of MEK inhibitors in MM have demonstrated a capacity to induce MM apoptosis by overcoming the prosurvival effects of the BMME, solid tumour studies indicate that the therapeutic benefit of MEK inhibitors alone are likely to be of limited benefit. Therefore, future clinical approaches require a shift towards using MEK inhibitors in combination with current anti-MM compounds and other novel small molecule inhibitors. The identification of relevant biomarkers of MEK inhibitor responses remains a high priority that can be used to predict patient sensitivity and to tailor individualised therapies.

References

Dhillon AS, Hagan S, Rath O, Kolch W . MAP kinase signalling pathways in cancer. Oncogene 2007; 26: 3279–3290.

McCubrey JA, Steelman LS, Chappell WH, Abrams SL, Wong EWT, Chang F et al. Roles of the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway in cell growth, malignant transformation and drug resistance. Biochim Biophys Acta 2007; 1773: 1263–1284.

Morabito F, Gentile M, Mazzone C, Bringhen S, Vigna E, Lucia E et al. Therapeutic approaches for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients in the era of novel drugs. Eur J Haematol 2010; 85: 181–191.

Zhan F, Huang Y, Colla S, Stewart JP, Hanamura I, Gupta S et al. The molecular classification of multiple myeloma. Blood 2006; 108: 2020–2028.

Hideshima T, Mitsiades C, Tonon G, Richardson PG, Anderson KC . Understanding multiple myeloma pathogenesis in the bone marrow to identify new therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Cancer 2007; 7: 585–598.

Malumbres M, Barbacid M . RAS oncogenes: The first 30 years. Nat Rev Cancer 2003; 3: 459–465.

Boguski MS, McCormick F . Proteins regulating Ras and its relatives. Nature 1993; 366: 643–654.

Hoshino R, Chatani Y, Yamori T, Tsuruo T, Oka H, Yoshida O et al. Constitutive activation of the 41-/43-kDa mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway in human tumors. Oncogene 1999; 18: 813–822.

Pritchard CA, Samuels ML, Bosch E, McMahon M . Conditionally oncogenic forms of the A-Raf and B-Raf protein kinases display different biological and biochemical properties in NIH 3T3 cells. Mol Cell Biol 1995; 15: 6430–6442.

Marais R, Light Y, Paterson HF, Mason CS, Marshall CJ . Differential regulation of Raf-1, A-Raf, and B-Raf by oncogenic Ras and tyrosine kinases. J Biol Chem 1997; 272: 4378–4383.

Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, Stephens P, Edkins S, Clegg S et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature 2002; 417: 949–954.

Solit DB, Garraway LA, Pratilas CA, Sawai A, Getz G, Basso A et al. BRAF mutation predicts sensitivity to MEK inhibition. Nature 2006; 439: 358–362.

Bonello L, Voena C, Ladetto M, Boccadoro M, Palestro G, Inghirami G et al. BRAF gene is not mutated in plasma cell leukemia and multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2003; 17: 2238–2240.

Alessi DR, Saito Y, Campbell DG, Cohen P, Sithanandam G, Rapp U et al. Identification of the sites in MAP kinase kinase-1 phosphorylated by p74(raf-1). EMBO J 1994; 13: 1610–1619.

Boulton TG, Nye SH, Robbins DJ, Ip NY, Radziejewska E, Morgenbesser SD et al. ERKs: a family of protein-serine/threonine kinases that are activated and tyrosine phosphorylated in response to insulin and NGF. Cell 1991; 65: 663–675.

Yoon S, Seger R . The extracellular signal-regulated kinase: multiple substrates regulate diverse cellular functions. Growth Factors 2006; 24: 21–44.

Kim HJ, Bar-Sagi D . Modulation of signalling by sprouty: a developing story. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2004; 5: 441–450.

Keyse SM . Dual-specificity MAP kinase phosphatases (MKPs) and cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2008; 27: 253–261.

Camps M, Nichols A, Arkinstall S . Dual specificity phosphatases: a gene family for control of MAP kinase function. FASEB J 2000; 14: 6–16.

Udell CM, Rajakulendran T, Sicheri F, Therrien M . Mechanistic principles of RAF kinase signaling. Cell Mol Life Sci 2011; 68: 553–565.

Catalanotti F, Reyes G, Jesenberger V, Galabova-Kovacs G, De Matos Simoes R, Carugo O et al. A Mek1-Mek2 heterodimer determines the strength and duration of the Erk signal. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2009; 16: 294–303.

Chesi M, Brents LA, Ely SA, Bais C, Robbiani DF, Mesri EA et al. Activated fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 is an oncogene that contributes to tumor progression in multiple myeloma. Blood 2001; 97: 729–736.

Neri A, Murphy JP, Cro L, Ferrero D, Tarella C, Baldini L et al. Ras oncogene mutation in multiple myeloma. J Exp Med 1989; 170: 1715–1725.

Liu P, Leong T, Quam L, Billadeau D, Kay NE, Greipp P et al. Activating mutations of N- and K-ras in multiple myeloma show different clinical associations: analysis of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group phase III trial. Blood 1996; 88: 2699–2706.

Bezieau S, Devilder MC, Avet-Loiseau H, Mellerin MP, Puthier D, Pennarun E et al. High incidence of N and K-Ras activating mutations in multiple myeloma and primary plasma cell leukemia at diagnosis. Hum Mutat 2001; 18: 212–224.

Bommert K, Bargou RC, Stuhmer T . Signalling and survival pathways in multiple myeloma. Eur J Cancer 2006; 42: 1574–1580.

Chng WJ, Gonzalez-Paz N, Price-Troska T, Jacobus S, Rajkumar SV, Oken MM et al. Clinical and biological significance of RAS mutations in multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2008; 22: 2280–2284.

Rasmussen T, Kuehl M, Lodahl M, Johnsen HE, Dahl IMS . Possible roles for activating RAS mutations in the MGUS to MM transition and in the intramedullary to extramedullary transition in some plasma cell tumors. Blood 2005; 105: 317–323.

Lentzsch S, Chatterjee M, Gries M, Bommert K, Gollasch H, Dörken B et al. P13-K/AKT/FKHR and MAPK signaling cascades are redundantly stimulated by a variety of cytokines and contribute independently to proliferation and survival of multiple myeloma cells. Leukemia 2004; 18: 1883–1890.

Chatterjee M, Stühmer T, Herrmann P, Bommert K, Dörken B, Bargou RC . Combined disruption of both the MEK/ERK and the IL-6R/STAT3 pathways is required to induce apoptosis of multiple myeloma cells in the presence of bone marrow stromal cells. Blood 2004; 104: 3712–3721.

Patriotis C, Makris A, Bear SE, Tsichlis PN . Tumor progression locus 2 (Tpl-2) encodes a protein kinase involved in the progression of rodent T-cell lymphomas and in T-cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993; 90: 2251–2255.

Gantke T, Sriskantharajah S, Sadowski M, Ley SC . IκB kinase regulation of the TPL-2/ERK MAPK pathway. Immunol Rev 2012; 246: 168–182.

Domina AM, Vrana JA, Gregory MA, Hann SR, Craig RW . MCL1 is phosphorylated in the PEST region and stabilized upon ERK activation in viable cells, and at additional sites with cytotoxic okadaic acid or taxol. Oncogene 2004; 23: 5301–5315.

Wuillème-Toumi S, Robillard N, Gomez P, Moreau P, Le Gouill S, Avet-Loiseau H et al. Mcl-1 is overexpressed in multiple myeloma and associated with relapse and shorter survival. Leukemia 2005; 19: 1248–1252.

Ley R, Balmanno K, Hadfield K, Weston C, Cook SJ . Activation of the ERK1/2 signaling pathway promotes phosphorylation and proteasome-dependent degradation of the BH3-only protein, Bim. J Biol Chem 2003; 278: 18811–18816.

Ohren JF, Chen H, Pavlovsky A, Whitehead C, Zhang E, Kuffa P et al. Structures of human MAP kinase kinase 1 (MEK1) and MEK2 describe novel noncompetitive kinase inhibition. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2004; 11: 1192–1197.

Dudley DT, Pang L, Decker SJ, Bridges AJ, Saltiel AR . A synthetic inhibitor of the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995; 92: 7686–7689.

Favata MF, Horiuchi KY, Manos EJ, Daulerio AJ, Stradley DA, Feeser WS et al. Identification of a novel inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase. J Biol Chem 1998; 273: 18623–18632.

Sebolt-Leopold JS, Dudley DT, Herrera R, Van Becelaere K, Wiland A, Gowan RC et al. Blockade of the MAP kinase pathway suppresses growth of colon tumors in vivo. Nat Med 1999; 5: 810–816.

LoRusso PM, Adjei AA, Varterasian M, Gadgeel S, Reid J, Mitchell DY et al. Phase I and pharmacodynamic study of the oral MEK inhibitor CI-1040 in patients with advanced malignancies. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 5281–5293.

Rinehart J, Adjei AA, LoRusso PM, Waterhouse D, Hecht JR, Natale RB et al. Multicenter phase II study of the oral MEK inhibitor, CI-1040, in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung, breast, colon, and pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 4456–4462.

Brown AP, Carlson TCG, Loi CM, Graziano MJ . Pharmacodynamic and toxicokinetic evaluation of the novel MEK inhibitor, PD0325901, in the rat following oral and intravenous administration. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2007; 59: 671–679.

LoRusso PM, Krishnamurthi SS, Rinehart JJ, Nabell LM, Malburg L, Chapman PB et al. Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the oral MAPK/ERK kinase inhibitor PD-0325901 in patients with advanced cancers. Clin Cancer Res 2010; 16: 1924–1937.

Haura EB, Ricart AD, Larson TG, Stella PJ, Bazhenova L, Miller VA et al. A phase II study of PD-0325901, an oral MEK inhibitor, in previously treated patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2010; 16: 2450–2457.

Huang W, Yang AH, Matsumoto D, Collette W, Marroquin L, Ko M et al. PD0325901, a mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase inhibitor, produces ocular toxicity in a rabbit animal model of retinal vein occlusion. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 2009; 25: 519–530.

Davies BR, Logie A, McKay JS, Martin P, Steele S, Jenkins R et al. AZD6244 (ARRY-142886), a potent inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase 1/2 kinases: mechanism of action in vivo, pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationship, and potential for combination in preclinical models. Mol Cancer Ther 2007; 6: 2209–2219.

Yeh TC, Marsh V, Bernat BA, Ballard J, Colwell H, Evans RJ et al. Biological characterization of ARRY-142886 (AZD6244), a potent, highly selective mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1/2 inhibitor. Clin Cancer Res 2007; 13: 1576–1583.

Huynh H, Soo KC, Chow PKH, Tran E . Targeted inhibition of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase pathway with AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther 2007; 6: 138–146.

Adjei AA, Cohen RB, Franklin W, Morris C, Wilson D, Molina JR et al. Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the oral, small-molecule mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1/2 inhibitor AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) in patients with advanced cancers. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 2139–2146.

Hainsworth JD, Cebotaru CL, Kanarev V, Ciuleanu TE, Damyanov D, Stella P et al. A phase II, open-label, randomized study to assess the efficacy and safety of AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) versus pemetrexed in patients with non-small cell lung cancer who have failed one or two prior chemotherapeutic regimens. JThorac Oncol 2010; 5: 1630–1636.

Bennouna J, Lang I, Valladares-Ayerbes M, Boer K, Adenis A, Escudero P et al. A Phase II, open-label, randomised study to assess the efficacy and safety of the MEK1/2 inhibitor AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) versus capecitabine monotherapy in patients with colorectal cancer who have failed one or two prior chemotherapeutic regimens. Invest New Drugs 2011; 25: 1021–1028.

O'Neil BH, Goff LW, Kauh JSW, Strosberg JR, Bekaii-Saab TS, Lee RM et al. Phase II study of the mitogen-activated protein kinase 1/2 inhibitor selumetinib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 2350–2356.

Goutopoulos A, Askew B, Bankston D, Clark A, Dhanabal M, Dong R et alAS703026: a novel allosteric MEK inhibitor. In: 100th Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research 2009; (Abstract [4776]).

Awada A, Houede N, Delord JP, Dubuisson M, Italiano A, Berge Y et alClinical, pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) results of first-in-man phase I trial of the orally available MEK-inhibitor MSC1936369 (AS703026) in patients (pts) with advanced solid tumors. In: 22nd AACR-NCI-EORTC Symposium on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics 2010; (Abstract [374]).

Johnston S XL518, a potent selective orally bioavailable MEK1 inhibitor, downregulates the RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK pathway in vivo, resulting in tumor growth inhibition and regression in pre-clinical models. In: 20th AACR-NCI-EORTC Symposium on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics 2007; (Abstract [C209]).

Rosen L, LoRusso P, Wee W, Goldman J, Weise A, Colevas AD et alA first-in-human phase 1 study to evaluate the MEK1/2 inhibitor GDC-0973 administered daily in patients with advanced solid tumors. In: 102nd Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research 2011; (Abstract [3611]).

Iverson C, Larson G, Lai C, Yeh LT, Dadson C, Weingarten P et al. RDEA119/BAY 869766: A potent, selective, allosteric inhibitor of MEK1/2 for the treatment of cancer. Cancer Res 2009; 69: 6839–6847.

Weekes C, Von Hoff DD, Adjei AA, Yeh LT, Leffingwell D, Sheedy B et alA multi-center Phase 1, dose-escalation trial to determine the safety and pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics of BAY 86-9766 (RDEA119), a MEK inhibitor, in advanced cancer patients. In: 22nd AACR-NCI-EORTC Symposium on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics 2010; (Abstract [109]).

Gilmartin AG, Kusnlerx AM, Sutton D, Moss KG, Thompson CS, Weber BL et alGSK1120212 is a novel Mek inhibitor demonstrating sustained inhibition of ERK phosphorylation and selective inhibition of B-Raf and RAS mutant cells in preclinical models. In: 20th AACR-NCI-EORTC Symposium on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics 2008; (Abstract [567]).

Gilmartin AG, Bleam MR, Groy A, Moss KG, Minthorn EA, Kulkarni SG et al. GSK1120212 (JTP-74057) is an inhibitor of MEK activity and activation with favorable pharmacokinetic properties for sustained in vivo pathway inhibition. Clin Cancer Res 2011; 17: 989–1000.

Gordon MS, Infante JR, Messersmith LA, Vogelzang NJ, Cox D, DeMarini DJ et alThe oral MEK1/MEK2 inhibitor, GSK1120212, effectively inhibits the MAPK pathway: pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and clinical response relationship. In: 22nd AACR-NCI-EORTC Symposium on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics 2010; (Abstract [373]).

Borthakur G, Popplewell L, Kirschbaum MH, Foran JM, Kadia TM, Jabbour E et al. Phase I/II trial of the MEK1/2 inhibitor GSK1120212 (GSK212) in patients (pts) with relapsed/refractory myeloid malignancies: evidence of activity in pts with RAS mutation [abstract]. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29 (suppl): abstr 6506.

Huynh H, Chow PKH, Soo KC . AZD6244 and doxorubicin induce growth suppression and apoptosis in mouse models of hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther 2007; 6: 2468–2476.

Haass NK, Sproesser K, Nguyen TK, Contractor R, Medina CA, Nathanson KL et al. The mitogen-activated protein/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase inhibitor AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) induces growth arrest in melanoma cells and tumor regression when combined with docetaxel. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14: 230–239.

Nishioka C, Ikezoe T, Yang J, Yokoyama A . Inhibition of MEK signaling enhances the ability of cytarabine to induce growth arrest and apoptosis of acute myelogenous leukemia cells. Apoptosis 2009; 14: 1108–1120.

McCubrey JA, Abrams SL, Ligresti G, Misaghian N, Wong EWT, Steelman LS et al. Involvement of p53 and Raf/MEK/ERK pathways in hematopoietic drug resistance. Leukemia 2008; 22: 2080–2090.

Yu C, Wang S, Dent P, Grant S . Sequence-dependent potentiation of paclitaxel-mediated apoptosis in human leukemia cells by inhibitors of the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Mol Pharmacol 2001; 60: 143–154.

Little AS, Balmanno K, Sale MJ, Newman S, Dry JR, Hampson M et al. Amplification of the driving oncogene, KRAS or BRAF, underpins acquired resistance to MEK1/2 inhibitors in colorectal cancer cells. Science Signaling 2011; 4: 166.

Corcoran RB, Dias-Santagata D, Bergethon K, Iafrate AJ, Settleman J, Engelman JA . BRAF gene amplification can promote acquired resistance to MEK inhibitors in cancer cells harboring the BRAF V600E mutation. Science Signaling 2010; 3: 149.

Wang H, Daouti S, Li WH, Wen Y, Rizzo C, Higgins B et al. Identification of the MEK1(F129L) activating mutation as a potential mechanism of acquired resistance to MEK inhibition in human cancers carrying the B-Raf V600E mutation. Cancer Res 2011; 71: 5535–5545.

Pratilas CA, Solit DB . Targeting the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway: physiological feedback and drug response. Clin Cancer Res 2010; 16: 3329–3334.

Steelman LS, Chappell WH, Abrams SL, Kempf RC, Long J, Laidler P et al. Roles of the Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR pathways in controlling growth and sensitivity to therapy-implications for cancer and aging. Aging (Milano) 2011; 3: 192–222.

Balmanno K, Chell SD, Gillings AS, Hayat S, Cook SJ . Intrinsic resistance to the MEK1/2 inhibitor AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) is associated with weak ERK1/2 signalling and/or strong PI3K signalling in colorectal cancer cell lines. Int J Cancer 2009; 125: 2332–2341.

Yoon YK, Kim HP, Han SW, Hur HS, Do YO, Im SA et al. Combination of EGFR and MEK1/2 inhibitor shows synergistic effects by suppressing EGFR/HER3-dependent AKT activation in human gastric cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther 2009; 8: 2526–2536.

Engelman JA, Chen L, Tan X, Crosby K, Guimaraes AR, Upadhyay R et al. Effective use of PI3K and MEK inhibitors to treat mutant Kras G12D and PIK3CA H1047R murine lung cancers. Nat Med 2008; 14: 1351–1356.

Bendell J, LoRusso P, Kwak E, Pandya S, Musib L, Jones C et alClinical combination of the MEK inhibitor GDC-0973 and the PI3K inhibitor GDC-0941: A first-in-human phase Ib study in patients with advanced solid tumors. In: 102nd Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research 2011; (Abstract [LB-89]).

Kurzrock R, Patnaik A, Rosenstein L, Fu S, Papadopoulos KP, Smith DA et al. Phase I dose-escalation of the oral MEK1/2 inhibitor GSK1120212 (GSK212) dosed in combination with the oral AKT inhibitor GSK2141795 (GSK795). J Clin Oncol 2011; 29 (suppl): abstr 3085.

Yoon YK, Kim HP, Han SW, Oh DY, Im SA, Bang YJ et al. KRAS mutant lung cancer cells are differentially responsive to MEK inhibitor due to AKT or STAT3 activation: implication for combinatorial approach. Mol Carcinog 2010; 49: 353–362.

Dai B, Meng J, Peyton M, Girard L, Bornmann WG, Ji L et al. STAT3 mediates resistance to MEK inhibitor through microRNA miR-17. Cancer Res 2011; 71: 3658–3668.

Laubach JP, Mahindra A, Mitsiades CS, Schlossman RL, Munshi NC, Ghobrial IM et al. The use of novel agents in the treatment of relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Leukemia: official journal of the Leukemia Society of America, Leukemia Research Fund, UK 2009; 23: 2222–2232.

Richardson PG, Weller E, Lonial S, Jakubowiak AJ, Jagannath S, Raje NS et al. Lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone combination therapy in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood 2010; 116: 679–686.

Cavo M, Tacchetti P, Patriarca F, Petrucci MT, Pantani L, Galli M et al. Bortezomib with thalidomide plus dexamethasone compared with thalidomide plus dexamethasone as induction therapy before, and consolidation therapy after, double autologous stem-cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a randomised phase 3 study. The Lancet 2010; 376: 2075–2085.

Podar K, Chauhan D, Anderson KC . Bone marrow microenvironment and the identification of new targets for myeloma therapy. Leukemia 2009; 23: 10–24.

Tai YT, Fulciniti M, Hideshima T, Song W, Leiba M, Li XF et al. Targeting MEK induces myeloma-cell cytotoxicity and inhibits osteoclastogenesis. Blood 2007; 110: 1656–1663.

Breitkreutz I, Raab MS, Vallet S, Hideshima T, Raje N, Chauhan D et al. Targeting MEK1/2 blocks osteoclast differentiation, function and cytokine secretion in multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol 2007; 139: 55–63.

Kim K, Kong SY, Fulciniti M, Li X, Song W, Nahar S et al. Blockade of the MEK/ERK signalling cascade by AS703026, a novel selective MEK1/2 inhibitor, induces pleiotropic anti-myeloma activity in vitro and in vivo. Br J Haematol 2010; 149: 537–549.

Mitsiades N, Mitsiades CS, Richardson PG, McMullan C, Poulaki V, Fanourakis G et al. Molecular sequelae of histone deacetylase inhibition in human malignant B cells. Blood 2003; 101: 4055–4062.

Bolden JE, Peart MJ, Johnstone RW . Anticancer activities of histone deacetylase inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2006; 5: 769–784.

Wolf JL, Siegel D, Jeffrey M, Lonial S, Goldschmidt H, Schmitt S et alA Phase II Study of Oral Panobinostat (LBH589) in Adult Patients with Advanced Refractory Multiple Myeloma. In: 50th ASH Annual Meeting and Exposition 2008; (Abstract [2774]).

Niesvizky R, Ely S, Mark T, Aggarwal S, Gabrilove JL, Wright JJ et al. Phase 2 trial of the histone deacetylase inhibitor romidepsin for the treatment of refractory multiple myeloma. Cancer 2011; 117: 336–342.

Sanchez E, Shen J, Steinberg J, Li M, Wang C, Bonavida B et al. The histone deacetylase inhibitor LBH589 enhances the anti-myeloma effects of chemotherapy in vitro and in vivo. Leuk Res 2011; 35: 373–379.

Ocio EM, Vilanova D, Atadja P, Maiso P, Crusoe E, Fernández-Lázaro D et al. In vitro and in vivo rationale for the triple combination of panobinostat (LBH589) and dexamethasone with either bortezomib or lenalidomide in multiple myeloma. Haematologica 2010; 95: 794–803.

Yu C, Dasmahapatra G, Dent P, Grant S . Synergistic interactions between MEK1/2 and histone deacetylase inhibitors in BCR/ABL+ human leukemia cells. Leukemia 2005; 19: 1579–1589.

Ozaki Ki, Kosugi M, Baba N, Fujio K, Sakamoto T, Kimura S et al. Blockade of the ERK or PI3K-Akt signaling pathway enhances the cytotoxicity of histone deacetylase inhibitors in tumor cells resistant to gefitinib or imatinib. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2010; 391: 1610–1615.

Drysdale MJ, Brough PA, Massey A, Jensen MR, Schoepfer J . Targeting Hsp90 for the treatment of cancer. Current Opinion in Drug Discovery and Development 2006; 9: 483–495.

Mitsiades CS, Mitsiades NS, McMullan CJ, Poulaki V, Kung AL, Davies FE et al. Antimyeloma activity of heat shock protein-90 inhibition. Blood 2006; 107: 1092–1100.

Khong T, Spencer A . Targeting HSP 90 induces apoptosis and inhibits critical survival and proliferation pathways in multiple myeloma. Mol Cancer Ther 2011; 10: 1909–1917.

Dry JR, Pavey S, Pratilas CA, Harbron C, Runswick S, Hodgson D et al. Transcriptional pathway signatures predict MEK addiction and response to selumetinib (AZD6244). Cancer Res 2010; 70: 2264–2273.

Annunziata CM, Hernandez L, Davis RE, Zingone A, Lamy L, Lam LT et al. Amechanistic rationale for MEK inhibitor therapy in myeloma based on blockade of MAF oncogene expression. Blood 2011; 117: 2396–2404.

Zingone A, Korde N, Chen J, Xi L, Raffled M, Holkova B et alMolecular Characterization and Clinical Correlations of MEK1/2 Inhibition (AZD6244) in Relapse or Refractory Multiple Myeloma: Analysis From a Phase II Study. In: 53rd ASH Annual Meeting and Exposition 2011; (Abstract [306]).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Chang-Yew Leow, C., Gerondakis, S. & Spencer, A. MEK inhibitors as a chemotherapeutic intervention in multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer Journal 3, e105 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/bcj.2013.1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bcj.2013.1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Combination therapy targeting Erk1/2 and CDK4/6i in relapsed refractory multiple myeloma

Leukemia (2022)

-

Bayesian graphical models for modern biological applications

Statistical Methods & Applications (2022)

-

Anti-tumor activity of the pan-RAF inhibitor TAK-580 in combination with KPT-330 (selinexor) in multiple myeloma

International Journal of Hematology (2022)

-

Selective Oral MEK1/2 Inhibitor Pimasertib: A Phase I Trial in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors

Targeted Oncology (2021)

-

NSD2 overexpression drives clustered chromatin and transcriptional changes in a subset of insulated domains

Nature Communications (2019)