Abstract

Inflammation and lipid disorders play crucial roles in synergistically accelerating the progression of diabetic nephropathy (DN). In this study we investigated how inflammation and lipid disorders caused tubulointerstitial injury in DN in vivo and in vitro. Diabetic db/db mice were injected with 10% casein (0.5 mL, sc) every other day for 8 weeks to cause chronic inflammation. Compared with db/db mice, casein-injected db/db mice showed exacerbated tubulointerstitial injury, evidenced by increased secretion of extracellular matrix (ECM) and cholesterol accumulation in tubulointerstitium, which was accompanied by activation of the CXC chemokine ligand 16 (CXCL16) pathway. In the in vitro study, we treated HK-2 cells with IL-1β (5 ng/mL) and high glucose (30 mmol/L). IL-1β treatment increased cholesterol accumulation in HK-2 cells, leading to greatly increased ROS production, ECM protein expression levels, which was accompanied by the upregulated expression levels of proteins in the CXCL16 pathway. In contrast, after CXCL16 in HK-2 cells was knocked down by siRNA, the IL-1β-deteriorated changes were attenuated. In conclusion, inflammation accelerates renal tubulointerstitial lesions in mouse DN via increasing the activity of CXCL16 pathway.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) remains the leading cause of end-stage renal disease worldwide. Although glomerulopathy is considered the main feature of DN, it is the extent of tubulointerstitial injury that ultimately determines the rate of depletion of renal function1. A growing body of evidence indicates that the tubulointerstitium plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of DN2. However, the pathogenetic mechanisms of tubulointerstitial injury in DN, which are fundamental to the development of a more effective preventive or therapeutic strategy, are undetermined.

Many studies have shown that inflammation is a cardinal mechanism in the pathophysiology of DN3. The increased levels of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) in the serum and urine are correlated with the progression of DN4,5. The expression level of monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) is increased in the diseased kidney, and genetic knockout of MCP-1 also alleviates albuminuria in diabetic mice6,7.

Recently, abnormal lipid metabolism and excess lipid accumulation in kidneys have been observed in diabetic rodents and have been presumed to accelerate the pathogenesis of DN8,9. However, the potential mechanisms of lipid accumulation in kidneys have not been completely elucidated.

CXC chemokine ligand 16 (CXCL16), which is also considered a scavenger receptor for phosphatidylserine and oxidized low-density lipoprotein (SR-PSOX), exists in two forms: surface-expressed and soluble. As a surface-expressed molecule, CXCL16 can act as a scavenger receptor for oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL) and promote adhesion to CXC chemokine receptor 6 (CXCR6)-expressing immune cells10,11. Soluble CXCL16 can be released from the cell surface by proteolytic cleavage via a disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing protein (ADAM)10 and ADAM1712,13. In recent years, studies have addressed the critical role of CXCL16 in kidney disease. Importantly, Gutwein et al found that the expression of CXCL16 was increased in kidney sections of diabetic mice and patients with DN14 suggesting that the activation of CXCL16 may induce excessive oxLDL uptake and aggravate the progression of DN.

Studies have shown that inflammation disrupts cholesterol homeostasis by increasing cholesterol uptake, inhibiting cholesterol efflux and impairing cholesterol synthesis15. This study aimed to evaluate whether inflammatory stress exacerbates tubulointerstitial injury by inducing lipid accumulation and to further explore the potential mechanisms of this process.

Materials and methods

Animal model

Eight-week-old male db/db mice (C57BL/KsJ genetic background, Grade III) were provided by the National Mode Animal Centre (Nanjing, China). The animals were studied according to standards and procedures approved by the Ethical Committee of Southeast University. The db/db mice were randomly assigned to receive subcutaneous injections with either 0.5 mL of distilled water or 0.5 mL of 10% casein (Sigma, St Louis, USA) every other day for 8 weeks (n=10). Casein was subcutaneously injected to induce systemic and local inflammation according to our previous studies16. Casein injection significantly increased the plasma levels of serum amyloid protein-A and TNF-α, increased the expression of MCP-1 and TNF-α and increased macrophage infiltration in the kidneys of db/db mice16. Twenty-four-hour urine samples were collected once a week from mice housed in metabolic cages. Upon termination, blood samples were collected for biochemical assays, and kidney samples were obtained for histological assessments and Western blot analysis.

Blood and urine measurements

Serum levels of triglycerides (TGs), total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) were measured by automatic analyzers (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). Albumin and creatinine in the urine were determined by ELISA (LifeSpan BioSciences, Seattle, USA) and a clinical biochemistry assay to calculate the albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR). The urine samples for albumin measurements were diluted by sample diluent with a volume ratio of 1:1. The urinary N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase (NAG) levels were detected with an ELISA kit (Jiancheng, Nanjing, China).

Histological examination

Paraffin sections (3 μm) of kidneys were used for periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining. Tubulointerstitium damage was quantified by Image-Pro Plus software. A total of 10 fields in each section were randomly selected to determine the integrated optical density (IOD) of lesions. Data are presented as IOD/area.

Electron microscopy

To observe ultramicrostructure changes in proximal tubular epithelial cells using transmission electron microscopy (TEM), the kidney tissues were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde. After ultrathin sectioning, the samples were observed with TEM in the VCU electron microscopy core facility.

Immunohistochemical staining

After deparaffinization and rehydration, paraffin sections (3 μm) of kidneys were submerged in 10 mmol/L sodium citrate buffer (pH=6.0) and microwaved for antigen unmasking. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 15 min at room temperature, and nonspecific antibody binding was blocked with 10% goat serum. Subsequently, sections were incubated with primary antibodies against TNF-α (1:100 dilution, Santa Cruz, Dallas, USA), MCP-1 (1:100 dilution, Santa Cruz, Dallas, USA), CD68 (1:100 dilution, Santa Cruz, Dallas, USA), fibronectin (1:100 dilution, Santa Cruz, Dallas, USA), α-smooth muscle actin (1:200 dilution, α-SMA, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), CXCL16 (1:100 dilution, R&D, Minneapolis, USA), ADAM10 (1:100 dilution, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and CXCR6 (1:200 dilution, NOVUS, Littleton, USA) overnight at 4 °C, followed by incubation with biotin-labeled secondary antibodies. Finally, slides were incubated in diaminobenzidine staining solution until a brown color was detected.

Immunofluorescence staining

After deparaffinization, the sections were placed in citrate-buffered solution and then microwaved for antigen retrieval. Subsequently, the sections were incubated with primary antibodies against CXCL16 (1:100 dilution, R&D, Minneapolis, USA) and Aquaporin-1 (AQP-1, 1:100 dilution, Santa Cruz, Dallas, USA) overnight at 4 °C, followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor-labeled secondary antibodies (1:1000 dilution, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA) at room temperature for 2 h. After washing, the samples were examined by confocal microscopy (×400).

Cell culture

Human renal proximal tubular epithelial (HK-2) cells were obtained from the China Center for Type Culture Collection (CCTCC) and cultured in DMEM/F12 containing 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin, 5 μg/mL insulin, 5 μg/mL transferrin, 0.4 μg/mL hydrocortisone, and 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, New York, USA). The cells were maintained in an incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and saturating humidity.

siRNA transfection

At 70% to 80% confluence, cells were synchronized with serum-free culture medium for 24 h and subsequently incubated with 30 mmol/L glucose (Sigma, St Louis, USA), and stimulated with 5 ng/mL recombinant human interleukin-1β (IL-1β, R&D, Minneapolis, USA), siRNA and transfection regents for another 24 h. The siRNA for CXCL16 and transfection regents were purchased from Invitrogen (StealthTM RNAi and RNAiMax reagent). The nonspecific sequence siRNA (StealthTM RNAi) was used as a negative control. HK-2 cells were transfected according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA).

Filipin staining

Lipid accumulation in HK-2 cells or in the kidneys of db/db mice was evaluated by Filipin staining. Briefly, samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and then stained with Filipin (50 ng/mL, Santa Cruz, Dallas, USA) for 30 min at room temperature. The results of Filipin staining were examined by laser microscopy (×200).

Quantitative measurements of intracellular free cholesterol/cholesterol ester

The lipids in kidney tissues or HK-2 cells were extracted by adding chloroform/methanol (2:1) to the samples. After ultrasonic treatment, the lipid phase was collected. Then, the samples were dried in a vacuum centrifuge and were then dissolved in 2-propanol containing 10% Triton X-100. Cholesterol ester hydrolase (Sigma, St Louis, USA) was used to hydrolyze cholesterol esters to free cholesterol in order to determine the amount of total cholesterol. The concentrations of total and free cholesterol per sample were determined using a standard curve and normalized against the total cell protein. The quantity of free cholesterol was subtracted from the total cholesterol to calculate the concentration of cholesterol ester.

Intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) measurement

Intracellular ROS in the HK-2 cells were detected using the cell-permeable probe dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) dissolved in anhydrous ethanol. The cells in 12-well plates were loaded with 10 μmol/L DCFH-DA and then incubated in 5% CO2 at 37 °C in the dark for 10 min. Subsequently, the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) three times and then examined by laser microscopy. The fluorescence intensity was quantified using Image J software.

Immunocytofluorescence staining

HK-2 cells cultured in chamber slides were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100 for 10 min, and then incubated with 5% BSA at room temperature for 30 min to block non-specific antigens. The cells were incubated with primary antibodies against CXCL16 (1:200 dilution, R&D, Minneapolis, USA), ADAM10 (1:200 dilution, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and CXCR6 (1:200 dilution, NOVUS, Littleton, USA) overnight at 4 °C, followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor-labeled secondary antibodies (1:1000 dilution, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA) at room temperature for 2 h.

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (real-time PCR)

One milliliter of Trizol (TaKaRa, Kusatsu, Japan) was added per well to extract total RNA from HK-2 cells, which were cultured in six-well plates. The reverse transcription reaction was performed using a commercially available kit (TaKaRa, Kusatsu, Japan). After cDNA synthesis by reverse transcription, separate aliquots of cDNA were used to amplify target genes using specific primers (shown in Table 1). SYBR Green dye was used to combine with double-stranded DNA. Real-time PCR was executed on an ABI PRISM 7300 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol (TaKaRa, Kusatsu, Japan), and mRNA expression was normalized to that of β-actin.

Western blotting

The total proteins were isolated from kidneys or cells and then denatured for future use. Equivalent aliquots of protein were added to each lane of a sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel for protein separation by electrophoresis. Protein was transferred from the gel to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. After blocking with blocking buffer for 1 h at room temperature, the membrane was incubated with primary antibodies against TNF-α (1:500 dilution), MCP-1(1:500 dilution), fibronectin (1:500 dilution), α-SMA (1:2000 dilution), CXCL16 (1:1000 dilution), ADAM10 (1:2000 dilution), and CXCR6 (1:2000 dilution) overnight at 4 °C. This incubation was then followed by incubation with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for another hour at 4 °C. Finally, the images were captured using an ECL Advanced™ system (GE Healthcare, USA). Protein expression levels were normalized to that of β-actin.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 20.0 software. Comparison between the two different groups was performed using unpaired Student's t test before expressing the results as a percentage of the control value. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Inflammation exacerbated tubular interstitial damage in db/db mice

Compared with the results for the db/db mice, there was significantly increased ACR in the db/db+casein mice as diabetes progressed (Figure 1A). Additionally, the level of N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase (NAG) in the urine, which was considered a marker of proximal tubular injury, was also apparently increased in the db/db+casein mice (Figure 1B). PAS staining demonstrated that inflammation exacerbated necrocytosis and cell detachment of the tubulointerstitium (Figure 1C, 1D). Transmission electron microscopy showed that inflammation aggravated mitochondrial damage, reduced the number of mitochondria and increased the number of vacuoles in the endochylema (Figure 1E). Moreover, there was increased protein expression of TNF-α and MCP-1 in the tubulointerstitium of casein-injected db/db mice (Figure 1F). Inflammation also significantly increased the protein expression of fibronectin and α-SMA in the kidneys of db/db mice (Figure 1G–I).

Inflammation exacerbated tubular interstitial damage in db/db mice. Eight-week-old diabetic db/db mice were randomly assigned to receive subcutaneous injections with either 0.5 mL distilled water (db/db) or 0.5 mL 10% casein (db/db+casein) every other day for 8 weeks (n=10). Albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR) was determined at each week in the mice (A, n=5). The quantitative analysis of the urinary NAG in the mice was conducted each week by ELISA (B, n=5). PAS staining of kidney. The arrow indicates damaged renal tubules (C, original magnification ×200). Quantification of tubulointerstitium damage using Image-Pro Plus software, and expressed as IOD/area, *P<0.05 vs db/db group (D, n=3). The change in the tubular cells was examined by transmission electron microscopy. The arrows indicate damaged mitochondria and vacuoles in the cytoplasm (E).

The immumohistochemical staining of TNF-α and MCP-1 in the kidneys of two groups of mice (original magnification ×400) (F). The protein expression levels of fibronectin and α-SMA in the kidneys of the mice were measured by immunohistochemical staining (G, brown color, original magnification ×400) and Western blotting (H and I, n=3). The histogram represents the mean±SD of the densitometric scans of the protein bands from the mice per group, normalized by comparison with β-actin; *P<0.05 vs db/db group.

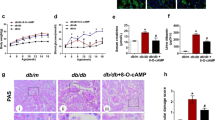

Inflammation increased lipid accumulation to accelerate tubulointerstitial injuries.

To investigate the underlying mechanisms of how inflammation intensifies tubulointerstitial injuries in db/db mice, we evaluated the effect of inflammation on lipid deposition in the tubulointerstitium. There was no significant difference in the serum levels of TC, TG, LDL and HDL between the two groups (Figure 2A). However, Filipin staining and a quantitative cholesterol assay both showed that more cholesterol accumulated in the tubulointerstitium in db/db+casein mice than in db/db mice (Figure 2B, 2C). An in vitro study confirmed that IL-1β treatment increased cholesterol accumulation in HK-2 cells (Figure 2D, 2E). These findings suggested that inflammation may exacerbate hyperglycemia-mediated tubulointerstitial damage by inducing intracellular cholesterol accumulation.

Inflammation increased lipid accumulation to accelerate tubulointerstitial injuries. Eight-week-old diabetic db/db mice were randomly assigned and received subcutaneous injections with either 0.5 mL distilled water (db/db, n=10) or 0.5 mL 10% casein (db/db+casein, n=10) every other day for 8 weeks. HK-2 cells were made quiescent using serum-free medium for 24 h, and treated with 30 mmol/L glucose (HG) or 30 mmol/L glucose plus 5 ng/mL IL-1β. TG, triglyceride; TC, total cholesterol; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein (A). Filipin staining was used to examine lipid accumulation both in vivo and in vitro (B and D, original magnification ×200). The concentration of cholesterol ester was measured both in vivo (C, n=5) and in vitro (E). The results represent the mean±SD. *P<0.05 vs db/db or HG group.

Inflammation-induced lipid accumulation increased ROS production and extracellular matrix (ECM) excretion in HK-2 cells

To evaluate the effects of lipid accumulation on tubular epithelium injuries, we examined ROS production and ECM expression in HK-2 cells. DCFH-DA showed that ROS production was significantly increased in the presence of IL-1β (Figure 3A, 3B). Moreover, the mRNA and protein expression levels of fibronectin and α-SMA were significantly increased in IL-1β-stimulated HK-2 cells (Figure 3C–3E). These data suggested that inflammation accelerates tubular epithelium injuries through lipid accumulation, which may be correlated with the increased ROS production and ECM excretion of tubular epithelial cells.

Inflammation-induced lipid accumulation increased ROS production and extracellular matrix (ECM) excretion in HK-2 cells. HK-2 cells were made quiescent using serum-free medium for 24 h and treated with 30 mmol/L glucose (HG) or 30 mmol/L glucose plus 5 ng/mL IL-1β. ROS staining was performed using DCFH-DA (A, original magnification ×200). The fluorescence intensity of ROS was calculated using Image J software (B). Real-time PCR (C) and Western blot were used to evaluate the expressions of fibronectin and α-SMA (D and E). The histogram represents the mean±SD of the densitometric scans of the protein bands per group, normalized by comparison with β-actin. *P<0.05 vs HG group.

Inflammation activated the CXCL16 pathway to induce lipid-mediated tubular interstitial damage in vivo and in vitro

Immunohistochemical staining and Western blotting showed that casein-injected db/db mice exhibited an increase in the protein expression levels of CXCL16, ADAM10 and CXCR6 (Figure 4A–4C). To clarify the location of CXCL16 expression in tubules, immunofluorescent staining of CXCL16 and AQP-1 (a specific biomarker of proximal tubules) was performed. The results showed that CXCL16 co-localized well with AQP-1. This suggests that CXCL16 is expressed in the proximal tubules (Figure 4D). Moreover, the mRNA and protein expression levels of CXCL16 pathway were increased in HK-2 cells under the stimulation of IL-1β (Figure 4E–4H). These results indicated that the inflammation-induced activation of the CXCL16 pathway may contribute to cellular lipid deposition and subsequent tubular interstitial damage.

Inflammation-activated CXCL16 pathway induced lipid-mediated tubular interstitial damage in vivo and in vitro. Eight-week-old diabetic db/db mice were randomly assigned and received subcutaneous injections with either 0.5 mL distilled water (db/db, n=10) or 0.5 mL 10% casein (db/db+casein, n=10) every other day for 8 weeks. HK-2 cells were made quiescent using serum-free medium for 24 h and treated with 30 mmol/L glucose (HG) or 30 mmol/L glucose plus 5 ng/mL of IL-1β. The protein expression levels of CXCL16, ADAM10 and CXCR6 were measured by immunohistochemical staining in vivo (A, brown color, original magnification ×400) and Western blot (B and C, n=3). Immunofluorescence staining of CXCL16 with AQP-1 (D, original magnification ×400) or CXCL16 pathway-related proteins (E, original magnification ×400), Real-time PCR (F) and Western blot (G and H) were used to evaluate the expression levels of CXCL16, ADAM10, and CXCR6, and the location of CXCL16 expression in tubules in vivo and in vitro. The histogram represents the mean±SD of the densitometric scans of the protein bands per group, normalized by comparison with β-actin. *P<0.05 vs db/db or HG group.

CXCL16 siRNA reduced lipid accumulation and consequently decreased ROS production and ECM excretion in HK-2 cells

Specific RNA interference was applied to knock down CXCL16 expression. As shown in Figure 5A–5D, CXCL16 siRNA significantly inhibited the mRNA and protein expression levels of the CXCL16 pathway-related molecules in HK-2 cells. Interestingly, lipid accumulation in HK-2 cells induced by IL-1β-stimulation was effectively reduced by CXCL16 siRNA (Figure 5E, 5F). Moreover, HK-2 cells cultivated with IL-1β exhibited a reduction in ROS production (Figure 5G-5H) and expression levels of fibronectin and α-SMA in the presence of CXCL16 siRNA (Figure 5I-5K). These data demonstrated that the inflammation-induced activation of CXCL16 pathway might be involved in the lipid accumulation and tubular epithelium injuries.

CXCL16 siRNA reduced lipid accumulation in HK-2 cells, which consequently decreased ROS production and ECM excretion. HK-2 cells were made quiescent using serum-free medium for 24 h and treated with 30 mmol/L glucose (HG) or 30 mmol/L glucose plus 5 ng/mL IL-1β. Immunofluorescence staining (A, original magnification ×400), real-time PCR (B) and Western blot (C and D) were used to evaluate the expression levels of CXCL16, ADAM10, and CXCR6. Filipin staining was used to examine lipid accumulation in each group (E).

The concentration of cholesterol ester in each group was measured (F). ROS staining was performed using DCFH-DA (G, original magnification ×200). The fluorescent intensity of ROS was calculated using Image J software (H). Real-time PCR (I) and Western blot (J and K) were used to evaluate the expression levels of fibronectin and α-SMA. The histogram represents the mean±SD of the densitometric scans of the protein bands per group, normalized by comparison with β-actin. *P<0.05 vs HG+IL-1β group.

Discussion

Inflammation and lipid disorders are critical pathogenic factors in DN. However, the precise mechanism of how inflammation and lipid disorders contribute to renal interstitial injury remains uncertain. In this study, using an inflamed diabetic mouse model induced by casein injection, we for the first time demonstrated that inflammation accelerated lipid accumulation in the tubulointerstitium and contributed to tubulointerstitial injury in db/db mice. Further study revealed that inflammation mediated lipid accumulation and tubular damage through upregulating CXCL16 pathway.

Although glomerulosclerosis has been regarded as the primary feature of DN, tubulointerstitial injury is also correlated with renal function and plays a critical role in the pathogenesis and progression of DN17. Inflammation is emerging as an important modulator of tubulointerstitial injury in DN. Monocytes, macrophages, T cells and mast cells mainly infiltrate the tubulointerstitium of DN. Inflammatory cytokines secreted from the tubulointerstitium significantly accelerated renal failure18. Proteinuria induced an increase in the expression levels of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines and adhesion molecules, which consequently increased the infiltration of inflammatory cells and contributed to local inflammation and tubulointerstitial damage3. Diabetic substrates, such as high glucose, proteinuria and advanced glycation end-products induced tubular interstitial damage by activating multiple inflammatory pathways, including nuclear factor kappa B, p38 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/22. Increasing evidence suggests that cellular receptors, including peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors, kinin receptors, protease-activated receptors and toll-like receptors, mediate interstitial inflammation in diabetic kidney disease19. Our previous study showed that casein injection induced systemic inflammation and local inflammation in the kidneys of db/db mice16. Of note, the secretion of urinary albumin and NAG were increased in inflamed db/db mice, suggesting that inflammation induced by casein might have a damaging effect on both the glomerulus and tubulointerstitium. Interestingly, there was a loss of body weight in db/db mice. The possible reason could be correlated with insulin resistance induced by inflammation20,21 or reduced food consumption.

Diabetes mellitus usually exhibits abnormal serum lipid metabolism, which is characterized by high triglycerides and LDL cholesterol levels, with predominantly small-dense LDL, and low HDL levels. Diabetic dyslipidemia has been shown to be associated with the development of cardiovascular disease and kidney dysfunction22. Studies have revealed that dyslipidemia might contribute to the progression of DN via Toll-like receptor 4 signaling, the renin-angiotensin system, transforming growth factor-β signaling, and oxidative stress23,24,25,26. Ruan et al proposed that inflammatory stress plays an important role in contributing to ectopic lipid accumulation15. Inflammation promoted the transportation of cholesterol from plasma to peripheral tissues. In peripheral tissues, inflammation induced an increase in cholesterol uptake, a decrease in cholesterol efflux and an increase in endogenic cholesterol synthesis. Our previous studies also showed that inflammatory stress exacerbated lipid accumulation in hepatic cells and vascular smooth muscle cells as well as multiple organs of db/db mice27,28,29. We also have revealed that inflammation-induced lipid deposition accelerated podocyte injury of db/db mice, which was mediated by dysregulation of LDLr30,31. It was found for the first time in this study that inflammation significantly increased lipid accumulation in the tubulointerstitium of db/db mice; however, we did not observe a difference in the plasma lipid profiles between the control and inflammation group, which might be explained by the lipid redistribution induced by inflammation. Ruan et al15 and our group27,28,29,30,32,33,34,35 demonstrated that inflammation induced lipid redistribution. In response to inflammation, lipid redistribution and accumulation in tissues might occur at several levels and sites: from circulation to tissue, from tissue to tissue, and from organelle to organelle15.

It is widely accepted that scavenger receptors on macrophages play a critical role in foam cell formation. Surface-expressed CXCL16 can work as a scavenger receptor for oxLDL, which was shown to facilitate cholesterol loading and lead to cell injury via generation of intracellular ROS36,37. Wuttge et al demonstrated that aortic CXCL16 levels were increased when ApoE-deficient mice were fed a high cholesterol diet, resulting in foam cell formation38. In our study, we found that inflammation significantly increased the expression levels of CXCL16 pathway-related proteins, and this was accompanied by the increased production of ECM and ROS in vivo and in vitro. Interestingly, with the application of CXCL16 siRNA, the lipid accumulation and production of ECM and ROS excretion in HK-2 cells were decreased, and cellular damage was alleviated accordingly.

Notably, an increase in the levels of soluble CXCL16 was shown to be pro-inflammatory and was associated with the plaque formation in patients with metabolic syndrome39. The expression of proximal tubular cell CXCL16 was upregulated in a tubulointerstitial inflammation model, and CXCL16 promoted an inflammatory response by stimulating the expression of cytokines in the tubulointerstitium40. Wang et al suggested that knockout of CXCL16 attenuated acetaminophen-induced liver injury by reducing chemokine formation and neutrophil accumulation41. These studies, in accordance with our findings, suggest that the inhibition of the CXCL16 pathway alleviates renal tubular interstitial injury by suppressing inflammatory response.

Moreover, we found that compared with controls, there were higher blood glucose levels in casein-injected db/db mice, which might result from insulin resistance induced by inflammation20,21. Thus, inflammation might indirectly accelerate kidney damage through increasing blood glucose level. Our previous study confirmed that high glucose accelerated DN by inducing lipid accumulation and cellular damage in podocytes31. Thus, in addition to inflammation, higher blood glucose levels might be partly responsible for the increase in tubulointerstitial damage. To confirm the sole effect of inflammation on tubulointerstitial damage, by in vitro study, we demonstrated that inflammatory stress induced lipid deposition, ROS production, and extracellular matrix accumulation in HK-2 cells through upregulating CXCL16 pathway.

In summary, in this study, we demonstrate that inflammation-induced activation of the CXCL16 pathway contributes to lipid accumulation in the tubulointerstitium, which results in tubulointerstitial injury and progression of DN. These data suggest that inhibition of the CXCL16 pathway might be a promising new strategy for the treatment of DN.

Author contribution

Ze-bo HU performed the research, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; Kun-ling MA designed and proofread the manuscript; Yang ZHANG, Gui-hua WANG, Liang LIU, Jian LU, Pei-pei CHEN, and Chen-chen LU assisted in the research; Bi-cheng LIU contributed reagents and statistical analyses.

References

Kitada M, Ogura Y, Monno I, Koya D . Regulating autophagy as a therapeutic target for diabetic nephropathy. Curr Diab Rep 2017; 17: 53.

Mauer M, Caramori ML, Fioretto P, Najafian B . Glomerular structural-functional relationship models of diabetic nephropathy are robust in type 1 diabetic patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015; 30: 918–23.

Cao Z, Cooper ME . Pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. J Diabetes Investig 2011; 2: 243–7.

Yacoub R, Campbell KN . Inhibition of RAS in diabetic nephropathy. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis 2015; 8: 29–40.

Ferrao F M, Lara L S, Lowe J . Renin-angiotensin system in the kidney: What is new? World J Nephrol 2014; 3: 64–76.

Vickers C, Hales P, Kaushik V, Dick L, Gavin J, Tang J, et al. Hydrolysis of biological peptides by human angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase. J Biol Chem 2002; 277: 14838–43.

Koka V, Huang XR, Chung AC, Wang W, Truong LD, Lan HY . Angiotensin II up-regulates angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ACE), but down-regulates ACE2 via the AT1-ERK/p38 MAP kinase pathway. Am J Pathol 2008; 172: 1174–83.

Xue H, Zhou L, Yuan P, Wang Z, Ni J, Yao T, et al. Counteraction between angiotensin II and angiotensin-(1-7) via activating angiotensin type I and Mas receptor on rat renal mesangial cells. Regul Pept 2012; 177: 12–20.

Lopez-Hernandez FJ, Lopez-Novoa JM . Role of TGF-beta in chronic kidney disease: an integration of tubular, glomerular and vascular effects. Cell Tissue Res 2012; 347: 141–54.

Lan HY . Diverse roles of TGF-beta/Smads in renal fibrosis and inflammation. Int J Biol Sci 2011; 7: 1056–67.

Meng XM, Tang P M, Li J, Lan HY . TGF-beta/Smad signaling in renal fibrosis. Front Physiol 2015; 6: 82.

Chen HY, Huang XR, Wang W, Li JH, Heuchel RL, Chung AC, et al. The protective role of Smad7 in diabetic kidney disease: mechanism and therapeutic potential. Diabetes 2011; 60: 590–601.

Mauer M, Zinman B, Gardiner R, Drummond KN, Suissa S, Donnelly SM, et al. ACE-I and ARBs in early diabetic nephropathy. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst 2002; 3: 262–9.

Jacobsen P, Andersen S, Jensen BR, Parving HH . Additive effect of ACE inhibition and angiotensin II receptor blockade in type I diabetic patients with diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 2003; 14: 992–9.

Mohamed RH, Abdel-Aziz HR, Abd E MD, Abd ET . Effect of RAS inhibition on TGF-beta, renal function and structure in experimentally induced diabetic hypertensive nephropathy rats. Biomed Pharmacother 2013; 67: 209–14.

Wang C, Min C, Rong X, Fu T, Huang X, Wang C . Irbesartan can improve blood lipid and the kidney function of diabetic nephropathy. Discov Med 2015; 20: 67–77.

Tong X, Drapkin R, Yalamanchili R, Mosialos G, Kieff E . The Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein 2 acidic domain forms a complex with a novel cellular coactivator that can interact with TFIIE. Mol Cell Biol 1995; 15: 4735–44.

Palacios L, Ochoa B, Gomez-Lechon MJ, Castell JV, Fresnedo O . Overexpression of SND p102, a rat homologue of p100 coactivator, promotes the secretion of lipoprotein phospholipids in primary hepatocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta 2006; 1761: 698–708.

Callebaut I, Mornon JP . The human EBNA-2 coactivator p100: multidomain organization and relationship to the staphylococcal nuclease fold and to the tudor protein involved in Drosophila melanogaster development. Biochem J 1997; 321: 125–32.

Caudy AA, Ketting RF, Hammond SM, Denli AM, Bathoorn AM, Tops BB, et al. A micrococcal nuclease homologue in RNAi effector complexes. Nature 2003; 425: 411–4.

Jariwala N, Rajasekaran D, Srivastava J, Gredler R, Akiel MA, Robertson CL, et al. Role of the staphylococcal nuclease and tudor domain containing 1 in oncogenesis. Int J Oncol 2015; 46: 465–73.

Rajasekaran D, Jariwala N, Mendoza RG, Robertson CL, Akiel M A, Dozmorov M, et al. Staphylococcal nuclease and tudor domain containing 1 (SND1 Protein) promotes hepatocarcinogenesis by inhibiting monoglyceride lipase (MGLL). J Biol Chem 2016; 291: 10736–46.

Wang Z, Ni J, Shao D, Liu J, Shen Y, Zhou L, et al. Elevated transcriptional co-activator p102 mediates angiotensin II type 1 receptor up-regulation and extracellular matrix overproduction in the high glucose-treated rat glomerular mesangial cells and isolated glomeruli. Eur J Pharmacol 2013; 702: 208–17.

Yang F, Chung AC, Huang XR, Lan HY . Angiotensin II induces connective tissue growth factor and collagen I expression via transforming growth factor-beta-dependent and -independent Smad pathways: the role of Smad3. Hypertension 2009; 54: 877–84.

Kong YL, Shen Y, Ni J, Shao DC, Miao NJ, Xu JL, et al. Insulin deficiency induces rat renal mesangial cell dysfunction via activation of IGF-1/IGF-1R pathway. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2016; 37: 217–27.

He M, Zhang L, Shao Y, Xue H, Zhou L, Wang XF, et al. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor mediated angiotensin II and high glucose induced decrease in renal prorenin/renin receptor expression. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2010; 315: 188–94.

Dalla VM, Saller A, Mauer M, Fioretto P . Role of mesangial expansion in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. J Nephrol 2001; 14 Suppl 4: S51–7.

Ponchiardi C, Mauer M, Najafian B . Temporal profile of diabetic nephropathy pathologic changes. Curr Diab Rep 2013; 13: 592–9.

Ellis EN, Warady BA, Wood EG, Hassanein R, Richardson WP, Lane PH, et al. Renal structural-functional relationships in early diabetes mellitus. Pediatr Nephrol 1997; 11: 584–91.

Burns KD . Angiotensin II and its receptors in the diabetic kidney. Am J Kidney Dis 2000; 36: 449–67.

Kennefick TM, Anderson S . Role of angiotensin II in diabetic nephropathy. Semin Nephrol 1997; 17: 441–7.

Leverson JD, Koskinen PJ, Orrico FC, Rainio EM, Jalkanen KJ, Dash AB, et al. Pim-1 kinase and p100 cooperate to enhance c-Myb activity. Mol Cell 1998; 2: 417–25.

Valineva T, Yang J, Palovuori R, Silvennoinen O . The transcriptional co-activator protein p100 recruits histone acetyltransferase activity to STAT6 and mediates interaction between the CREB-binding protein and STAT6. J Biol Chem 2005; 280: 14989–96.

Paukku K, Yang J, Silvennoinen O . Tudor and nuclease-like domains containing protein p100 function as coactivators for signal transducer and activator of transcription 5. Mol Endocrinol 2003; 17: 1805–14.

Paukku K, Kalkkinen N, Silvennoinen O, Kontula KK, Lehtonen JY . p100 increases AT1R expression through interaction with AT1R 3'-UTR. Nucleic Acids Res 2008; 36: 4474–87.

Izquierdo MC, Martin-Cleary C, Fernandez-Fernandez B, Elewa U, Sanchez-Niño MD, Carrero JJ, et al. CXCL16 in kidney and cardiovascular injury. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2014; 25: 317–25.

Nosadini R, Tonolo G . Role of oxidized low density lipoproteins and free fatty acids in the pathogenesis of glomerulopathy and tubulointerstitial lesions in type 2 diabetes. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2011; 21: 79–85.

Wuttge DM, Zhou X, Sheikine Y, Wågsäter D, Stemme V, Hedin U, et al. CXCL16/SR-PSOX is an interferon-gamma-regulated chemokine and scavenger receptor expressed in atherosclerotic lesions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2004; 24: 750–5.

Lv Y, Hou X, Ti Y, Bu P . Associations of CXCL16/CXCR6 with carotid atherosclerosis in patients with metabolic syndrome. Clin Nutr 2013; 32: 849–54.

Izquierdo MC, Sanz AB, Mezzano S, Blanco J, Carrasco S, Sanchez-Niño MD, et al. TWEAK (tumor necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis) activates CXCL16 expression during renal tubulointerstitial inflammation. Kidney Int 2012; 81: 1098–107.

Wang H, Shao Y, Zhang S, Xie A, Ye Y, Shi L, et al. CXCL16 deficiency attenuates acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity through decreasing hepatic oxidative stress and inflammation in mice. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2017; 49: 541–9.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No 81470957), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (No BK20141343), the Jiangsu Province Six Talent Peaks Project (No 2015-WSN-002), the project for Jiangsu Provincial Medical Talent (No ZDRCA2016077), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No KYZZ15-0061), the Jiangsu Province Ordinary University Graduate Research Innovation Project (No SJZZ16-004), and the Clinical Medical Science Technology Special Project of Jiangsu Province (No BL2014080).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, Zb., Ma, Kl., Zhang, Y. et al. Inflammation-activated CXCL16 pathway contributes to tubulointerstitial injury in mouse diabetic nephropathy. Acta Pharmacol Sin 39, 1022–1033 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/aps.2017.177

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/aps.2017.177

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Baicalin attenuates adriamycin-induced nephrotic syndrome by regulating fibrosis procession and inflammatory reaction

Genes & Genomics (2021)

-

Parthenolide ameliorates tweak-induced podocytes injury

Molecular Biology Reports (2020)

-

Caspase-11 promotes renal fibrosis by stimulating IL-1β maturation via activating caspase-1

Acta Pharmacologica Sinica (2019)