Abstract

Matrine is an alkaloid extracted from a Chinese herb Sophora flavescens Ait, which has shown chemopreventive potential against various cancers. In this study, we evaluated the anticancer efficacy of a novel derivative of matrine, (6aS, 10S, 11aR, 11bR, 11cS)-10- methylamino-dodecahydro- 3a,7a-diazabenzo (de) (MASM), against human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells and their corresponding sphere cells in vitro and in vivo. Human HCC cell lines (Hep3B and Huh7) were treated with MASM. Cell proliferation was assessed using CCK8 and colony assays; cell apoptosis and cell cycle distributions were examined with flow cytometry. The expression of cell markers and signaling molecules was detected using Western blot and qRT-PCR analyses. A sphere culture technique was used to enrich cancer stem cells (CSC) in Hep3B and Huh7 cells. The in vivo antitumor efficacy of MASM was evaluated in Huh7 cell xenograft model in BALB/c nude mice, which were administered MASM (10 mg·kg−1·d−1, ig) for 3 weeks. After the treatment was completed, tumor were excised and weighed. A portion of tumor tissue was enzymatically dissociated to obtain a single cell suspension for the spheroid formation assays. MASM (2, 10, 20 μmol/L) dose-dependently inhibited the proliferation of HCC cells, and induced apoptosis, which correlated with a reduction in Bcl-2 expression and an increase in PARP cleavage. MASM also induced cell cycle arrest in G0/G1 phase, which was accompanied by increased p27 and decreased Cyclin D1 expression. Interestingly, MASM (2, 10, and 20 μmol/L) drastically reduced the EpCAM+/CD133+ cell numbers, suppressed the sphere formation, inhibited the expression of stem cell marker genes and promoted the expression of mature hepatocyte markers in the Hep3B and Huh7 spheroids. Additionally, MASM dose-dependently suppressed the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and AKT/GSK3β/β-catenin signaling pathways in Hep3B and Huh7 cells. In Huh7 xenograft bearing nude mice, MASM administration significantly inhibited Huh7 xenograft tumor growth and markedly reduced the number of surviving cancer stem-like cells in the tumors. MASM administration also reduced the expression of stem cell markers while increasing the expression of mature hepatocyte markers in the tumor tissues. The novel derivative of matrine, MASM, markedly suppresses HCC tumor growth through multiple mechanisms, and it may be a promising candidate drug for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a common primary malignancy and a leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide1. Currently, surgical resection, liver transplantation, and chemotherapy are the standard therapies for HCC. However, surgical resections are not suitable for numerous HCC patients with advanced stage tumors, and the available chemotherapeutic drugs show limited efficacies in HCC therapy2,3,4. Therefore, there is a need to explore more effective anti-HCC drugs and therapeutic approaches.

Studies have shown that cancer stem cells (CSC) exist in multiple cancer types, including HCC5,6,7,8,9. They are believed to drive tumor growth and recurrence through continuous self-renewal and differentiation. Currently available chemotherapeutic drugs primarily inhibit the growth of differentiated tumor cells with little or no impact on CSC. Thus, the development of novel drugs that target both CSCs and differentiated cancer cells may improve treatments for malignant tumors.

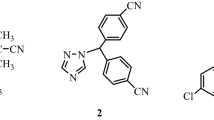

Matrine, oxymatrine, sophocarpine and other sophora alkaloids are the main extractable alkaloid components in Sophora flavescens Ait, a Chinese herb. They exhibit various biological activities that comprise anti-cancer, anti-inflammation, anti-virus, anti-fibrosis, anti-arrhythmia, and immunosuppressive effects10,11,12,13,14,15. However, the clinical potential of the sophora alkaloids remains limited because of their relatively low activities and short half-lives12,15,16. To improve their therapeutic efficacies, we have designed and synthesized multiple matrine derivatives by transforming sophocarpine into thiosophocarpine using Lawesson's reagent and subsequently introducing various amino groups to the keto beta position using the Michael addition reaction. One derivative [(6aS, 10S, 11aR,11bR, 11cS)-10-methylamino-dodecahydro-3a,7a-diazabenzo (de) anthracene-8-thione] MASM (Figure 1A) exhibits a higher anti-inflammatory activity toward macrophages compared with matrine and sophocarpine17. MASM exerts in vitro activities within a concentration range of 1–20 μmol/L, which is markedly lower than the concentration range for the sophora alkaloids (100–200 μmol/L). Our previous study indicates that MASM can inhibit lipopolysaccharides (LPS)-induced maturation of murine bone marrow-derived dendritic cells18. Additionally, we have demonstrated that MASM potently suppresses hepatic stellate cell activation and ameliorates experimental hepatic fibrosis that is associated with the inhibition of AKT signaling pathways19. However, the MASM effects on liver cancer cells remain unknown. This study aims to investigate MASM effects on human HCC cell lines (Hep3B and Huh7) and its in vivo anti-tumor activity, corresponding sphere cells and underlying mechanisms.

The effect of MASM on Hep3B and Huh7 cell proliferation and colony formation. (A) Chemical structure of MASM. (B, C) MASM inhibited Hep3B (B) and Huh7 (C) cell proliferation as determined by the CCK-8 assay. (D, E) MASM suppressed colony formation by human hepatoma cells. n=3. *P<0.05 vs control.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and antibodies

MASM maleate (>98% purity) was synthesized in our laboratory and dissolved in saline. CHIR99021 (CHIR) was purchased from Selleck (Houston, TX, USA). Recombinant human basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF), recombinant human epidermal growth factor (EGF), and DMEM/F-12 were purchased from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ, USA). B27 (×50), and Insulin-Transferrin-Selenium (ITS, ×100) were purchased from Gibco BRL. L-glutamine (×100) was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). The anti-CD133 (AC133)-phycoerythrin (PE) and anti-CD326 (EpCAM)-allophycocyanin (APC) antibodies and isotype-matched mouse anti-IgG1-PE and anti-IgG1-APC were purchased from MiltenyiBiotec (North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany). Antibodies against phospho-PI3K (Tyr458), AKT, phospho-AKT (Ser473), phospho-AKT (Thr308), mTOR, phospho-mTOR (Ser2448), phospho-P70S6K (Thr389), β-catenin, GSK-3β, phospho-GSK-3β (Ser9), and epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). Antibodies against Cyclin D1 and glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The IRDye680-conjugated anti-rabbit and anti-mouse secondary antibodies were purchased from Rockland (Gilbertsville, PA, USA).

Cell culture

The Hep3B and Huh7 human hepatoma cell lines and the LO2 normal hepatocyte line were provided by the Shanghai Cell Bank (Shanghai Institute for Biological Science, Chinese Academy of Science, Shanghai, China). All cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, Invitrogen), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 50 mg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator.

Cell proliferation and colony formation assay

Hep3B or Huh7 cells (2×103 cells/well) were seeded into 96-well plates and treated with MASM (0–20 μmol/L) for 24, 48, and 72 h. Cell proliferation was assessed using a Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK8, Dojindo Laboratories, Tokyo, Japan). The proliferation inhibition rates were calculated using the following equation: Inhibition (%)=[(ODcontrol−ODdrug)/ODcontrol]×100. HCC cells (1×103 cells/well) were treated with or without MASM in 6-well plates and allowed to grow for 17 to 21 days. Colonies were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue.

Apoptosis analysis

HCC cells were treated with MASM for 24 h. Apoptosis was detected using a Hoechst 33258 fluorescence staining kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, China) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Morphologic changes to the apoptotic cells were recorded with a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The MASM effect on cell apoptosis was also assessed using the Annexin-V/propidium iodide double-labeled flow cytometry kit (KeyGen, Nanjing, China). Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

Cell cycle analysis

HCC cells were treated with MASM for 24 h. The cell cycle distributions were determined by propidium iodide (PI) staining and followed by flow cytometric analysis according to the instructions provided in the cell cycle detection kit (Shanghai R&S Biotech Co, Ltd, Shanghai, China).

Tumor sphere formation assay and flow cytometric analysis

Sphere cultures were performed as previously described9 with minor modifications. Briefly, primary sphere cells were obtained by culturing HCC cells in sphere-forming conditioned Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/Ham's F12 medium (DMEM/F12, HyClone, Logan, UT) supplemented with FGF (20 ng/mL), EGF (20 ng/mL), B27 (1×), ITS (1×), and L-glutamine (1×) in 96-well ultra-low attachment plates (Corning, Lowell, MA). The primary sphere cells (1×103 cells/well) were incubated with or without MASM for 7 d. The second and third passages of the cells were grown for 7 d in the absence of MASM. The number of spheres (>30 μm in diameter) was counted, and spheres were photographed under a phase contrast microscope.

To examine MASM effects on the subpopulation of cells that expressed EpCAM and CD133, cells were incubated with anti-AC133-PE and anti-EpCAM-APC antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry. Isotype-matched mouse anti-IgG1-PE and anti-IgG1-APC were used as controls.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis was performed as previously described18. Total cellular RNA was isolated with the RNAfast200 kit (Fastagen Biotech Company). cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using the PrimeScript RT reagent Kit (Takara, Dalian, China), and the PCR amplification was performed in triplicate on a StepOnePlusTM real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, USA) using the SYBR Premix Ex TaqTM PCR Kit (Takara, Dalian, China). The primer sequences of the detected genes follow:

EpCAM (F: 5′-GCTCTGAGCGAGTGAGAACCT-3′, R: 5′-GACCAGGATCCAGATCCAGTTG-5′), CD133 (F: 5′-ACATGAAAAGACCTGGGGG-3′, R: 5′-GATCTGGTGT CCCAGCATG-3′), Sox2 (F: 5′-GCGAACCATCTCTGTGGTCT-3′, R: 5′-GGAAAGTTGGGATCGAACAA-3′), Oct3/4 (F: 5′-CGACCATCTGCCGCTTTGAG-3′, R: 5′-CCCCCTGTCCCCCATTCCTA-3′), cytochrome P450(CYP)1A3 (F: 5′-CTGGCCTCTGCCATCTTCTG-3′, R: 5′-TTAGCCTCCTTGCTCACATGC-3′), glucose-6-phosphatase (G-6-P) (F: 5′-GGCTCCATGACTGTGGGATC-3′, R: 5′-TTCAGCTGCACAGCCCAGAA-3′), albumin (ALB) (F: 5′-AGCCT AAGGCAGCTTGACTT-3′, R: 5′-CTCGATGAACTTCGGGATGA-3′) and β-actin (F: 5′-ACCCACACTGTGCCCATCTATG-3′, R: 5′-AGAGTACTTGCGCTCAGGAGGA-3′).

Western blot

Western blot analyses were performed as previously described18. Briefly, a total protein sample of approximately 20 μg was resolved by SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis and transferred to a PVDF membrane. The proteins were probed with the indicated primary antibodies followed by an incubation with an IRDye 800CW anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibody (LI-COR Biotechnology, Nebraska). Detection was performed using an Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR Biotechnology, Nebraska). The band intensities were quantified by densitometry.

In vivo xenograft model assay

BALB/c nude mice were subcutaneously (sc) injected with 2×106 Huh7 cells to establish the HCC xenograft model. Drug treatments were initiated 24 h after the cell injections. Animals were administered saline or MASM (10 mg/kg, orally by daily gavage) for 3 weeks. The tumor sizes were measured and calculated using the following formula: 1/2×LW2, where L denotes the longest surface length (mm) and W denotes the width (mm). Each tumor tissue was excised and weighed when the experiment was completed. A portion of each tumor tissue was enzymatically dissociated to obtain a single cell suspension for the spheroid formation assays, and the remaining tumor tissue was used for the RT-PCR analysis.

The Animal Care and Use Committee of the Second Military Medical University approved all animal tests and experimental protocols, which were performed in accordance with the care and use of laboratory animals.

Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as the mean±SD. Statistical analyses were performed using the one-way analysis of variance or the two-tailed Student's t test. P<0.05 was considered as the minimum level of significance.

Results

MASM inhibits hepatoma cell proliferation and colony formation

The MASM treatment inhibited Hep3B and Huh7 cell proliferation in a concentration- and time-dependent manner (Figure 1B and 1C). MASM also markedly reduced the number of colonies in the clonogenic assays (Figure 1D and 1E). Notably, the LO2 immortalized human hepatocyte cell line and rat primary hepatocytes were not affected by MASM at the concentrations that were tested (data not shown), indicating that HCC cells are more sensitive to MASM than normal cells.

MASM induces hepatoma cell apoptosis

The Hoechst 33258 stains of the MASM-treated Hep3B and Huh7 cells revealed a condensed or fragmented chromatin staining pattern with brilliant blue fluorescent dots in the hepatoma cell nuclei compared with a uniformly blue staining pattern in the control cells (Figure 2A). The Annexin V-FITC and PI staining results showed an increase in apoptotic cells as the MASM concentration increased (Figure 2B). The analysis of the apoptosis regulators demonstrated a concentration-dependent reduction in the Bcl-2 protein levels by MASM with an accompanying increase in cleaved Poly (ADPribose) polymerase (PARP) expression (Figure 2C).

MASM induces Hep3B and Huh7 cell apoptosis. (A) Hoechst 33258 staining of Hep3B and Huh7 cells, which were treated with MASM for 24 h, was visualized by fluorescence microscopy. Arrows indicate the apoptotic cells. (B) Hepatoma cells were treated with MASM for 24 h and labeled with AnnexinV and PI, followed by flow cytometric analysis. The results represent three independent experiments. The quantitative apoptotic cell data are shown. n=3. Mean±SD. *P<0.05 vs control. (C) Western blot analysis of hepatoma cells treated with MASM for 24 h. The indicated antibodies were used. The band intensities were quantified. The results were normalized to the GAPDH loading control. n=3. Mean±SD. *P<0.05 vs control.

MASM induces cell cycle arrest in hepatoma cells

The 24-h MASM treatments (10 and 20 μmol/L) significantly increased the proportions of Hep3B and Huh7 cells in G0/G1 (Figure 3A and 3B). The analysis of the cell cycle regulatory proteins revealed that MASM noticeably decreased Cyclin D1 and CDK2 expression in Hep3B and Huh7 cells, which was accompanied by increased p27 expression (Figure 3C).

MASM induces cell cycle arrest in Hep3B and Huh7 cells. (A) Cells were treated with MASM for 24 h, stained with propidium iodide and subjected to flow cytometric analysis. The results represent three independent experiments. (B) Quantitative data for the cell cycle distributions. n=3. Mean±SD. *P<0.05 vs control. (C) The cell cycle-associated protein levels in hepatoma cells treated with MASM for 24 h. A representative Western blot of three independent experiments is shown. The band intensities were quantified. The results were normalized to the GAPDH loading control. n=3. Mean±SD. *P<0.05 vs control.

MASM inhibits hepatic cancer stem-like cells

To investigate whether MASM suppressed HCC CSCs, we enriched the hepatic CSC populations in the Hep3B and Huh7 cell lines using the sphere culture technique. The flow cytometric analysis demonstrated that the EpCAM+/CD133+ cells accounted for 97.0% and 94.1% of the Hep3B and Huh7 sphere cells, respectively. MASM (10 and 20 μmol/L) potently reduced the fraction of EpCAM+/CD133+ cells (Figure 4A). The MASM treatment clearly reduced the numbers and sizes of the primary Hep3B and Huh7 spheres (Figure 4B and 4C). Moreover, the number of spherical colonies significantly decreased when MASM-treated primary spheres were cultured for the subsequent two passages in the absence of drug (Figure 4D). The real-time PCR results showed that the MASM treatment drastically suppressed the expression of stem cell marker genes, including CD133, EpCAM, Sox2 and Oct3/4, and concomitantly up-regulated the expression of mature hepatocyte markers (ALB, CYP1A3 and G-6-P) (Figure 4E).

The effect of MASM on hepatic cancer stem-like cells. (A) MASM reduced the proportion of EpCAM+/CD133+ cells in the spheres treated with MASM for 72 h. (B) MASM suppressed primary Hep3B and Huh7 sphere formation. n=3. Mean±SD. *P<0.05 versus control. (C) MASM reduced the sizes of Hep3B and Huh7 primary spheres (magnification, ×400). (D) MASM-treated primary spheres exhibited reduced self-renewal capacities. In the absence of MASM, MASM-treated primary spheres formed fewer spheres in the subsequent two passages compared with the control-treated primary spheres. n=3. Mean±SD. *P<0.05 vs control. (E) MASM decreased the expression of stem cell markers (CD133, EpCAM, Sox2, and Oct3/4) and increased the expression of mature hepatocyte markers (ALB, CYP1A3, and G-6-P) in two sphere types as determined by quantitative PCR. The mRNA levels were normalized to β-actin and are relative to the control. n=3. Mean±SD. *P<0.05 vs control.

MASM suppresses the PI3K/AKT and GSK3β/β-catenin pathways in hepatoma cells

MASM markedly reduced phosphorylation of PI3K P110а (the catalytic subunit of PI3K) at Tyr458 in Hep3B and Huh7 cells. The degrees of AKT phosphorylation at Ser473 and Thr308 were concomitantly decreased while no significant change was observed in the total AKT levels. Moreover, MASM reduced phosphorylation of an AKT downstream signaling molecule, mTOR(Ser2448) as well as the mTOR substrate, P70S6K(Thr389) (Figure 5).

MASM inhibits the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in hepatoma cells. Hep3B and Huh7 cells were treated with the indicated MASM concentrations for 24 h. Western blotting was performed to determine the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling-related protein levels. The band intensities were quantified. The results were normalized to the GAPDH loading control. n=3. Mean±SD. *P<0.05 vs control.

MASM markedly reduced the β-catenin and Cyclin D1 protein levels in Hep3B and Huh7 cells (Figure 6A and 6C). Because β-catenin is phosphorylated at Ser33/Ser37/Thr41 by GSK3β for its degradation20, we also examined whether MASM affected phosphorylation of GSK3β (Ser9) and β-catenin (Ser33/Ser37/Thr41). As shown in Figure 6A, MASM markedly reduced GSK3β (Ser9) phosphorylation with no evident impact on total GSK3β expression. Accordingly, MASM treatment increased phosphorylation of β-catenin (Ser33/Ser37/Thr41) and decreased β-catenin protein levels, while phosphorylation of β-catenin (Ser675) remained unchanged (Figure 6B). Conversely, CHIR21 (a GSK3β inhibitor) increased phosphorylation of GSK3β (Ser9) and suppressed phosphorylation of β-catenin (Ser33/Ser37/Thr41) but not of β-catenin (Ser675); β-catenin protein levels increased. When co-treated with CHIR, the effects of MASM on GSK3β phosphorylation, β-catenin phosphorylation (Ser33/Ser37/Thr41), and β-catenin accumulation were attenuated (Figure 6B and 6D). Because GSK3β phosphorylation at Ser9 results in its inhibition and subsequently stabilizes β-catenin, these results suggest that MASM-induced β-catenin degradation is mediated through activation of GSK3β22,23.

MASM suppresses the GSK3β/β-catenin pathway in hepatoma cells. Hep3B and Huh7 cells were treated with MASM and/or GSK3β inhibitor CHIR for 4 d. (A, C) Concentration-dependent reduction of GSK3β (Ser9) phosphorylation and decrease in β-catenin and Cyclin D1 protein levels by MASM. n=3. Mean±SD. *P<0.05 vs control. (B, D) CHIR partially reversed the effects of MASM on phosphorylated GSK3β (Ser9), phosphorylated β-catenin (Ser33/37/Thr41), and β-catenin in Hep3B and Huh7 cells. n=3. Mean±SD. *P<0.05 vs control. #P<0.05 vs MASM.

MASM inhibits HCC xenograft tumor growth and reduces CSCs in vivo

MASM significantly inhibited the growth and weights of the Huh7 xenografts in nude mice (Figure 7A and 7B). No remarkable weight loss was observed in the MASM-treated mice (Figure 7C). Moreover, MASM markedly reduced the number of tumor sphere-forming cells in the xenograft tumors as determined by in vitro tumor sphere formation assays (Figure 7D). Accordingly, the EpCAM, CD133, Sox2, and Oct3/4 mRNA levels were significantly decreased in the MASM-treated tumors, which exhibited accompanying increases in ALB, CYP1A3, and G-6-P expression (Figure 7E).

MASM inhibits Huh-7 xenograft tumor growth in nude mice. (A) Time course of tumor volumes. (B) Images and tumor weights of excised tumors. (C) Body weights of mice. (D) Spheroid colony formation of cancer cells isolated from dissociated Huh7 tumors. (E) mRNA levels of stemness and liver-specific genes in tumor tissues. n=5. Mean±SD. *P<0.05 vs control.

Discussion

Matrine has been shown to exert potential activities against various cancers, including hepatocellular carcinoma, gastric cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, leukemia, colon carcinoma and gallbladder carcinoma, by inhibiting cancer cell proliferation, accelerating apoptosis, inducing cell cycle arrest and suppressing metastasis24,25,26,27,28,29,30. However, these in vitro activities require concentrations as high as 100–200 μmol/L. This prompted us to modify matrine to achieve a new matrine derivative (MASM) with a markedly improved pharmacological activity. Our in vitro experiments have shown that MASM significantly inhibits LPS-induced murine macrophage activation, dendritic cell maturation, and rat hepatic stellate cell activation within the 1–20 μmol/L concentration range, which is approximately 10 times lower than that for matrine17,18,19. Moreover, the in vivo anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects of MASM at 1–10 mg/kg were comparable to those of matrine at 30–100 mg/kg when the drugs were orally administered by gavage to mice, and there were no apparent side effects or toxicities (Our unpublished data). In this study, we evaluated MASM effects on the Hep3B and Huh7 human HCC cell lines and their corresponding sphere cells in vitro as well as on a Huh7 cell xenograft model in BALB/c nude mice in vivo.

Our in vitro data showed that MASM significantly inhibited Hep3B and Huh7 cellular proliferation and colony formation. Importantly, immortalized human hepatocytes were not affected by any of the MASM concentrations tested here, which is consistent with our previous reports that show an absence of MASM effects on rat primary hepatocyte proliferation or rat primary hepatic stellate cell apoptosis19. These data suggest a specificity of MASM for hepatoma cells.

Chemotherapeutic agents utilize two important mechanisms for reducing cancer cell numbers—apoptosis induction and cell cycle arrest. In this study, MASM significantly induced hepatoma cell apoptosis as assessed by Hoechst 33258 staining and FACS analysis. This apoptotic effect correlated with a decreased expression of the Bcl-2 anti-apoptotic protein and an increased expression of cleaved PARP, which contributes to the onset of apoptosis31,32. MASM also induced growth arrest of hepatoma cells at G0/G1, with the following expression changes to key cell-cycle regulatory proteins associated with G0/G1 arrest: an increase in p27 and a decrease in Cyclin D1. Cyclin D1 expression correlates with cancer cell proliferation, whereas increases to p27 are associated with inhibited proliferation33. Thus, the antiproliferative effect of MASM on hepatoma cells is associated with cell apoptosis and cell cycle arrest.

Recent reports describe the use of the sphere culture technique and flow cytometry to successfully enrich and characterize hepatic CSCs in HCC cell lines and tissues7,8,9. In this study, we enriched populations of hepatic cancer stem-like cells by using a sphere culture technique. Consistent with previous studies9, Hep3B and Huh7 cells easily formed spheroid colonies after being cultured with serum-free media, and Hep3B and Huh7 sphere cells exhibited self-renewal capacities and expressed CSC membrane biomarkers (EpCAM and CD133). Using the two sphere cell types as models, we found that the MASM treatment noticeably decreased the positive EpCAM/CD133 cell fraction as assessed by FACS analysis, which appeared to be associated with a suppressed self-renewal capability of these cancer stem-like cells and with the promotion of cancer stem-like cell differentiation into hepatocytes. We found that both the numbers and sizes of the spheres were markedly reduced after the MASM treatment. Furthermore, the number of sphere-forming cells in the subsequent two passages, which were cultured without MASM, was also clearly reduced. Additionally, the expression of stem cell markers was reduced while the expression of mature hepatocyte markers was increased in the MASM-treated Hep3B and Huh7 spheroids. Importantly, the MASM in vitro activity on hepatic cancer stem-like cells was substantiated by our in vivo experiments. MASM (10 mg/kg) administration for 21 d significantly inhibited Huh7 xenograft tumor growth and markedly reduced the number of surviving cancer stem-like cells in the tumors as determined by sphere culture. Moreover, a reduced expression of stem cell markers that was accompanied by an increased expression of mature hepatocyte markers was observed in tumor tissues from the MASM-treated animals. Notably, we did not use the side populations of the cells or the sorted cancer stem cells when we investigated the MASM effects on the hepatic CSCs or when we assessed the ability of MASM-treated residual cancer stem cells to initiate tumors upon secondary implantation in NOD/SCID mice34. Although these results are preliminary, this study suggests that the MASM inhibitory effect on hepatic CSCs may contribute to its antitumor activity.

The PI3K/AKT pathway has a critical regulatory role in the signal transduction activity associated with cell proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation and survival35,36. PI3K/AKT signaling deregulation is implicated in the initiation and progression of multiple human malignancies37. Recently, an AKT inhibitor has been demonstrated to potently reduce the number of brain cancer stem cells. The decline was associated with a preferential induction of apoptosis and a suppression of neurosphere formation38. We have previously found that MASM targets the AKT signaling pathway and inhibits hepatic stellate cell activation and dendritic cell maturation18,19. In agreement with these studies, we showed that MASM suppressed the PI3K/AKT pathway in HCC cells, which was evidenced by reduced phosphorylation of AKT, its upstream factor (PI3K p110) as well as two downstream signaling molecules, mTOR and p70S6K. Therefore, the downregulation of the PI3K/AKT pathway might have contributed to the inhibitory effect of MASM on HCC cells and hepatic CSCs. We also found that MASM inhibited the Wnt/β-catenin self-renewal pathway, which plays an important role in stem cells and cancer39,40. MASM reduced phosphorylation of GSK3β(Ser9), which resulted in increasing phosphorylation of β-catenin (Ser33/Ser37/Thr41) and ultimately decreasing β-catenin as well as its target gene, Cyclin D1. Moreover, a specific GSK3β inhibitor (CHIR) reversed MASM-induced β-catenin phosphorylation (Ser33/Ser37/Thr41) and degradation. These results suggest that MASM suppresses the PI3K/AKT pathway and subsequent GSK3β activation, β-catenin phosphorylation and degradation to ultimately inhibit hepatic CSC self-renewal. Further studies are needed to clarify the exact role of such downregulation in the inhibition of HCC CSCs by MASM.

In conclusion, we have shown that MASM is an effective inhibitor of HCC tumor growth with low toxicity. Furthermore, this study demonstrates that MASM suppresses hepatoma cell proliferation, induces cell apoptosis and growth arrest, inhibits hepatic CSCs and suppresses the AKT/mTOR/p70S6K and AKT/GSK3β/β-catenin signaling pathways, offering possible mechanisms for its antitumor activity. Our study provides a foundation for further preclinical and clinical evaluations of MASM as a hepatocellular carcinoma therapeutic.

Author contribution

Zhi-gao HE and Jun-ping ZHANG designed the experiments; Ying LIU, Yang QI, and Zhi-hui BAI performed the experiments; Chen-xu NI, Qi-hui REN, Wei-heng XU, and Jing XU wrote the manuscript and analyzed the data; Hong-gang HU, Lei QIU, and Jian-zhong LI revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

References

Ferrin G, Aguilar-Melero P, Rodriguez-Peralvarez M, Montero-Alvarez JL, de la Mata M . Biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma: diagnostic and therapeutic utility. Hepatic Med 2015; 7: 1–10.

El-Serag HB, Siegel AB, Davila JA, Shaib YH, Cayton-Woody M, McBride R, et al. Treatment and outcomes of treating of hepatocellular carcinoma among Medicare recipients in the United States: a population-based study. J Hepatol 2006; 44: 158–66.

Davila JA, Duan Z, McGlynn KA, El-Serag HB . Utilization and outcomes of palliative therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: a population-based study in the United States. J Clin Gastroenterol 2012; 46: 71–7.

Thomas MB, O'Beirne JP, Furuse J, Chan AT, Abou-Alfa G, Johnson P . Systemic therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: cytotoxic chemotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol 2008; 15: 1008–14.

Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL . Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature 2001; 414: 105–11.

Ma S, Chan KW, Hu L, Lee TK, Wo JY, Ng IO, et al. Identification and characterization of tumorigenic liver cancer stem/progenitor cells. Gastroenterology 2007; 132: 2542–56.

Yamashita T, Honda M, Nakamoto Y, Baba M, Nio K, Hara Y, et al. Discrete nature of EpCAM+ and CD90+ cancer stem cells in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2013; 57: 1484–97.

Yamashita T, Ji J, Budhu A, Forgues M, Yang W, Wang HY, et al. EpCAM-positive hepatocellular carcinoma cells are tumor-initiating cells with stem/progenitor cell features. Gastroenterology 2009; 136: 1012–24.

Xu X, Liu RF, Zhang X, Huang LY, Chen F, Fei QL, et al. DLK1 as a potential target against cancer stem/progenitor cells of hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther 2012; 11: 629–38.

Huang WC, Chan CC, Wu SJ, Chen LC, Shen JJ, Kuo ML, et al. Matrine attenuates allergic airway inflammation and eosinophil infiltration by suppressing eotaxin and Th2 cytokine production in asthmatic mice. J Ethnopharmacol 2014; 151: 470–7.

Long Y, Lin XT, Zeng KL, Zhang L . Efficacy of intramuscular matrine in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatobil Pancreatic Dis Int 2004; 3: 69–72.

Zhang JP, Zhang M, Zhou JP, Liu FT, Zhou B, Xie WF, et al. Antifibrotic effects of matrine on in vitro and in vivo models of liver fibrosis in rats. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2001; 22: 183–6.

Li X, Chu W, Liu J, Xue X, Lu Y, Shan H, et al. Antiarrhythmic properties of long-term treatment with matrine in arrhythmic rat induced by coronary ligation. Biol Pharm Bull 2009; 32: 1521–6.

Li T, Wong VK, Yi XQ, Wong YF, Zhou H, Liu L . Matrine induces cell energy in human Jurkat T cells through modulation of mitogen-activated protein kinases and nuclear factor of activated T-cells signaling with concomitant up-regulation of anergy-associated genes expression. Biol Pharm Bull 2010; 33: 40–6.

Yong J, Wu X, Lu C . Anticancer advances of matrine and its derivatives. Curr Pharm Des 2015; 21: 3673–80.

Zhang L, Liu W, Zhang R, Wang Z, Shen Z, Chen X, et al. Pharmacokinetic study of matrine, oxymatrine and oxysophocarpine in rat plasma after oral administration of Sophora flavescens Ait. extract by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2008; 47: 892–8.

Hu H, Wang S, Zhang C, Wang L, Ding L, Zhang J, et al. Synthesis and in vitro inhibitory activity of matrine derivatives towards pro-inflammatory cytokines. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2010; 20: 7537–9.

Xu J, Qi Y, Xu WH, Liu Y, Qiu L, Wang KQ, et al. Matrine derivate MASM suppresses LPS-induced phenotypic and functional maturation of murine bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. Int Immunopharmacol 2016; 36: 59–66.

Xu WH, Hu HG, Tian Y, Wang SZ, Li J, Li JZ, et al. Bioactive compound reveals a novel function for ribosomal protein S5 in hepatic stellate cell activation and hepatic fibrosis. Hepatology 2014; 60: 648–60.

Liu C, Li Y, Semenov M, Han C, Baeg GH, Tan Y, et al. Control of beta-catenin phosphorylation/degradation by a dual-kinase mechanism. Cell 2002; 108: 837–47.

Bock AS, Leigh ND, Bryda EC . Effect of Gsk3 inhibitor CHIR99021 on aneuploidy levels in rat embryonic stem cells. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 2014; 50: 572–9.

Cohen P, Frame S . The renaissance of GSK3. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2001; 2: 769–76.

Cross DA, Alessi DR, Cohen P, Andjelkovich M, Hemmings BA . Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin mediated by protein kinase B. Nature 1995; 378: 785–9.

Zhang Z, Wang X, Wu W, Wang J, Wang Y, Wu X, et al. Effects of matrine on proliferation and apoptosis in gallbladder carcinoma cells (GBC-SD). Phytother Res 2012; 26: 932–7.

Chang C, Liu SP, Fang CH, He RS, Wang Z, Zhu YQ, et al. Effects of matrine on the proliferation of HT29 human colon cancer cells and its antitumor mechanism. Oncol lett 2013; 6: 699–704.

Zhang J, Li Y, Chen X, Liu T, Chen Y, He W, et al. Autophagy is involved in anticancer effects of matrine on SGC-7901 human gastric cancer cells. Oncol Rep 2011; 26: 115–24.

Zhang Y, Zhang H, Yu P, Liu Q, Liu K, Duan H, et al. Effects of matrine against the growth of human lung cancer and hepatoma cells as well as lung cancer cell migration. Cytotechnology 2009; 59: 191–200.

Zhang S, Zhang Y, Zhuang Y, Wang J, Ye J, Zhang S, et al. Matrine induces apoptosis in human acute myeloid leukemia cells via the mitochondrial pathway and Akt inactivation. PLoS One 2012; 7: e46853.

Zhang JQ, Li YM, Liu T, He WT, Chen YT, Chen XH, et al. Antitumor effect of matrine in human hepatoma G2 cells by inducing apoptosis and autophagy. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16: 4281–90.

Li LQ, Li XL, Wang L, Du WJ, Guo R, Liang HH, et al. Matrine inhibits breast cancer growth via miR-21/PTEN/Akt pathway in MCF-7 cells. Cell Physiol Biochem 2012; 30: 631–41.

de Murcia G, Menissier de Murcia J . Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase: a molecular nick-sensor. Trends Biochem Sci 1994; 19: 172–6.

Liu LF . DNA topoisomerase poisons as antitumor drugs. Annu Rev Biochem 1989; 58: 351–75.

Matsuda Y, Wakai T, Kubota M, Takamura M, Yamagiwa S, Aoyagi Y, et al. Clinical significance of cell cycle inhibitors in hepatocellular carcinoma. Med Mol Morphol 2013; 46: 185–92.

Li Y, Zhang T, Korkaya H, Liu S, Lee HF, Newman B, et al. Sulforaphane, a dietary component of broccoli/broccoli sprouts, inhibits breast cancer stem cells. Clin Cancer Res 2010; 16: 2580–90.

Song HK, Kim J, Lee JS, Nho KJ, Jeong HC, Kim J, et al. Pik3ip1 modulates cardiac hypertrophy by inhibiting PI3K pathway. PloS One 2015; 10: e0122251.

Pene F, Claessens YE, Muller O, Viguie F, Mayeux P, Dreyfus F, et al. Role of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt and mTOR/P70S6-kinase pathways in the proliferation and apoptosis in multiple myeloma. Oncogene 2002; 21: 6587–97.

Li GY, Jung KH, Lee H, Son MK, Seo J, Hong SW, et al. A novel imidazopyridine derivative, HS-106, induces apoptosis of breast cancer cells and represses angiogenesis by targeting the PI3K/mTOR pathway. Cancer Lett 2013; 329: 59–67.

Eyler CE, Foo WC, LaFiura KM, McLendon RE, Hjelmeland AB, Rich JN . Brain cancer stem cells display preferential sensitivity to Akt inhibition. Stem Cells 2008; 26: 3027–36.

Yang W, Yan HX, Chen L, Liu Q, He YQ, Yu LX, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling contributes to activation of normal and tumorigenic liver progenitor cells. Cancer Res 2008; 68: 4287–95.

Reya T, Clevers H . Wnt signalling in stem cells and cancer. Nature 2005; 434: 843–50.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No 81270508) and the National Major Special Science and Technology Project (No 2012ZX09103101-043). The funding agency had no role in the actual experimental design, analysis, or writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Qi, Y., Bai, Zh. et al. A novel matrine derivate inhibits differentiated human hepatoma cells and hepatic cancer stem-like cells by suppressing PI3K/AKT signaling pathways. Acta Pharmacol Sin 38, 120–132 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/aps.2016.104

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/aps.2016.104

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A novel nitidine chloride nanoparticle overcomes the stemness of CD133+EPCAM+ Huh7 hepatocellular carcinoma cells for liver cancer therapy

BMC Pharmacology and Toxicology (2022)

-

Tumor microenvironment: a prospective target of natural alkaloids for cancer treatment

Cancer Cell International (2021)

-

Matrine attenuates pathological cardiac fibrosis via RPS5/p38 in mice

Acta Pharmacologica Sinica (2021)

-

Bacterial cytochrome P450-catalyzed regio- and stereoselective steroid hydroxylation enabled by directed evolution and rational design

Bioresources and Bioprocessing (2020)

-

Crystal structure-based comparison of two NAMPT inhibitors

Acta Pharmacologica Sinica (2018)