Abstract

Aim:

To investigate the mechanisms underlying the anti-nociceptive effect of minocycline on bone cancer pain (BCP) in rats.

Methods:

A rat model of BCP was established by inoculating Walker 256 mammary carcinoma cells into tibial medullary canal. Two weeks later, the rats were injected with minocycline (50, 100 μg, intrathecally; or 40, 80 mg/kg, ip) twice daily for 3 consecutive days. Mechanical paw withdrawal threshold (PWT) was used to assess pain behavior. After the rats were euthanized, spinal cords were harvested for immunoblotting analyses. The effects of minocycline on NF-κB activation were also examined in primary rat astrocytes stimulated with IL-1β in vitro.

Results:

BCP rats had marked bone destruction, and showed mechanical tactile allodynia on d 7 and d 14 after the operation. Intrathecal injection of minocycline (100 μg) or intraperitoneal injection of minocycline (80 mg/kg) reversed BCP-induced mechanical tactile allodynia. Furthermore, intraperitoneal injection of minocycline (80 mg/kg) reversed BCP-induced upregulation of GFAP (astrocyte marker) and PSD95 in spinal cord. Moreover, intraperitoneal injection of minocycline (80 mg/kg) reversed BCP-induced upregulation of NF-κB, p-IKKα and IκBα in spinal cord. In IL-1β-stimulated primary rat astrocytes, pretreatment with minocycline (75, 100 μmol/L) significantly inhibited the translocation of NF-κB to nucleus.

Conclusion:

Minocycline effectively alleviates BCP by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway in spinal astrocytes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bone cancer pain (BCP) is a unique type of chronic pain that derives from primary bone sarcomas or metastases from breast, lung, prostate, or other solid tumors. BCP consists of a triad of states, namely, tonic pain or ongoing pain, spontaneous pain, and movement-induced pain1,2,3, and it substantially influences the survival and quality of life of cancer patients4. To date, the existing treatment for BCP remains deficient.

Over the previous few decades, BCP models have been successfully established5, and there is increasing evidence that indicates spinal astrocytes participate in the process6,7 by releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines7,8,9. Moreover, nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), an important transcriptional factor mediating cytokine production8,10,11, is activated in spinal astrocytes during a chronic pain state8,12. Therefore, blocking NF-κB may represent a therapeutic strategy for relieving pain13,14,15.

Minocycline, a second generation tetracycline antibiotic, selectively inhibits microglia. However, accumulating evidence indicates that it prevents chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) via the inhibition of astrocytes16,17,18,19. Moreover, it has also been demonstrated that minocycline down-regulates NF-κB activity in several other cell lines20,21. Whether minocycline alleviates BCP by inhibiting NF-κB in spinal astrocytes has not been fully explored and understood. Therefore, the present study was designed to examine the mechanisms underlying the effects of minocycline on BCP.

Materials and methods

Animals

Virgin female Wistar rats (180–200 g, specific pathogen-free grade) were supplied by the Experimental Animal Research Center of Hubei Province, Wuhan, China (No 42000600006171). Animals were housed under standard conditions (individually maintained at a temperature of 22±2 °C, 12/12-h light/dark cycle, with ad libitum access to food and water). All experiments were conducted with the approval of the Animal Care and Use Committee of Huazhong University of Science and Technology and were in accordance with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (revised 2011).

The experimental protocol is as illustrated in Figure 1. Five days prior to the start of the study, an intrathecal cannula operation was performed. At d 0, rat BCP models were established with the inoculation of Walker 256 mammary carcinoma cells. To assess pain perception, a mechanical paw withdrawal threshold (PWT) test was performed prior to BCP surgery and at d 3, 7, and 14. Tissues were harvested to identify morphological changes in the tibial bone or PSD95, GFAP, NF-κB p65, p-IKKα, and IκBα changes in the spinal cord. To determine the analgesic effects of minocycline, the drug was administered from d 14 twice per day for 3 consecutive days. The mechanical PWT was tested at d 14, 15, 16, and 17. The spinal cords were collected to investigate the mechanisms of minocycline at d 17.

Schematic diagram of the experimental design. BCP, bone cancer pain; PWT, paw withdrawal threshold.

Intrathecal catheters implant

Intrathecal cannula operation was performed 5 d prior to the BCP operation, as described in our previous reports22,23. Briefly, after the animals were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (40 mg/kg, intraperitoneal injection [ip]), a polyethylene catheter (PE-10 tube), with an inner diameter of 0.3 mm and an outer diameter of 0.6 mm (PE-0503, Anilab Software & Instruments, Ningbo, China), was implanted 5 mm cephalad into the lumbar subarachnoid space through the L4–L5 intervertebral space. An intrathecal injection of 1% lidocaine (10 μL) was used to confirm the catheter position. The rat was eliminated if there were signs of nerve injury. The outside terminus was sealed after each injection.

Preparation of Walker 256 mammary carcinoma cells

Walker 256 mammary carcinoma cells were inoculated into the abdominal cavity of female Wistar rats. After 7 d, cells were extracted from the ascites, washed with D-Hank's solution, and centrifuged at 500×g for 5 min at 4 °C (5 cycles). The cells were subsequently calibrated at a concentration of 4×107/mL and maintained on ice until inoculation.

BCP modeling

Rat BCP models were established using previously described methods7,23,24,25. In brief, under anesthesia with pentobarbital sodium (40 mg/kg, ip), rats were placed in a supine position, and the right leg was shaved and disinfected with 7% iodine. A minimally invasive incision was made parallel to the tibia to expose the plateau. A 23-gauge needle was inserted into the tibial medullary canal to create a pathway for carcinoma cell injection and was subsequently replaced with a 10-μL Hamilton syringe. A volume of 10 μL that contained Walker 256 mammary carcinoma cells (approximately 4×105) was slowly injected into the intramedullary space of the right tibia in the BCP group (n=48), whereas an equivalent volume of D-Hank's solution was injected into the sham rats (n=9). The injection site was sealed with bone wax as soon as the syringe was retracted, and the skin was subsequently sutured with 4-0 silk thread (SA83G, Johnson & Johnson Medical (China) Ltd, Shanghai, China). All rats were placed on a warm pad until full recovery from anesthesia; once recovered, the rats were transferred to their individual cages.

Bone histology

Right tibial bones were collected from euthanized rats for bone histological investigation. The bones were post-fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 72 h, decalcified in 10% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (pH=7.4) for 3 weeks, and decalcified in decalcifying solution for 24 h. The tibias were washed, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 5-μm thick sections, which were stained with hematoxylin and eosin to investigate carcinoma cell invasion and bone destruction.

Mechanical paw withdrawal threshold (PWT) test

The mechanical PWT test was performed on d 0, 3, 7, and 14 at 09:00 AM. To identify the effects of minocycline on PWT, measurements for drug- or vehicle-treated BCP rats were obtained 1 h prior to administration. The results from d 14 after the Walker 256 mammary carcinoma cell inoculation were set as the baseline, and measurements were obtained every day for the next 3 d. The examiner was blind to the drug treatments. The rats were placed in individual Plexiglas chambers (10 cm×10 cm×15 cm) with a wire net floor (graticule: 0.5 cm×0.5 cm) and were habituated for 30 min. Similar to our previous reports23,26, a range of von Frey filaments (1-, 1.4-, 2-, 4-, 6-, 8-, 10-, and 15-g bending force; Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL, USA), starting with 1 g and ending with 15 g in ascending order, were applied to determine the PWT. The duration of each stimulus was maintained for approximately 1 s. Each monofilament was applied five times with a 10-s interval between applications. Quick withdrawal or paw flinching was considered a positive response. The threshold for sensitivity to mechanical stimuli was recorded as the bending force of the filament for which at least 60% of the applications elicited a response.

Drug administration protocol

Thirty-nine rats in the BCP group were randomly distributed into six subgroups: vehicle (saline) intrathecal group (n=6), minocycline 50 μg intrathecal group (n=6), minocycline 100 μg intrathecal group (n=6), vehicle ip group (n=6), minocycline 40 mg/kg ip group (n=6), and minocycline 80 mg/kg ip group (n=9). Fourteen days after Walker 256 mammary carcinoma cell inoculation, the drug treatment was initiated. Minocycline hydrochloride (purity>99%, S4226, Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX, USA) was freshly dissolved in saline prior to each injection. The dose in the present experiment was selected based on previous relevant reports27,28 and our preliminary results29. The drug solution was intrathecally injected in a volume of 10 μL, followed by a volume of 5 μL of saline to flush the catheter. The ip injected animals received a dose of 1 mL/100 g twice per day for three consecutive days.

Western blotting analysis

On d 14, six BCP rats and six sham rats were deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (60 mg/kg, ip). The lumbar 2–5 (L2–5) segments of the whole spinal cord were rapidly collected, whereas the minocycline or vehicle treated rats were euthanized on d 17. The total proteins were extracted on ice using RIPA lysis buffer (50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 0.5% DOC, 1% NP40, 0.1% SDS, 1 mmol/L NaF, 1 mmol/L Na3VO4). Nuclear proteins were prepared according to the protocol for the Protein Extraction Kit (P1201, Applygen, Beijing, China). Following centrifugation (16 000×g, 4 °C, 30 min), the supernatants were collected, and the protein concentration was determined using the Bradford method and standardized. The protein samples were heated for 10 min at 95 °C with sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) buffer. Equivalent amounts of protein (20–50 μg) were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and subsequently eletrotransferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (IPVH00010, Millipore, Bellerica, MA, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin in Tris-buffered saline and Tween 20 (TBST, 0.1%) at room temperature (23±2 °C) for 2 h. The membranes were then incubated over night at 4 °C with the primary antibodies against NF-κB p65 (1:500, MAB3026, Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, 1:1500, 04-1062, Merck Millipore), postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD95, 1:1000, 04-1066, Merck Millipore), β-actin (1:3000, P0015, Promoter, Wuhan, China), phosphorylated IκB kinase α (p-IKKα) (1:500, AP0173, ABclonal, Wuhan, China), IκBα (1:500, A1187, ABclonal Biotech), and Lamin B1 (1:400, BA1761-1, Boster, Wuhan, China). After washing three times for 10 min each with TBST, the membranes were cultured for 2 h with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat-anti-mouse (1:5000, P0008, Promoter, Wuhan, China) or goat-anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:5000, P0009, Promoter, Wuhan, China). The bands of the target proteins were visualized via chemiluminescence (32209, Thermo, Rockford, IL, USA) and measured using a computerized image analysis system (BIO-RAD, ChemiDoc XRS+, CA, USA).

Immunohistochemistry

At d 14 after tumor cell inoculation, three tumor rats and three sham rats were euthanized under pentobarbital sodium anesthesia (60 mg/kg), and three BCP rats treated with 100 mg/kg minocycline were euthanized at d 17. The L2–5 sections of the spinal cord were removed following perfusion with 200 mL of saline and 500 mL of 4% PFA; the tissues were post-fixed in 4% PFA for 24 h and equilibrated with 30% sucrose in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) overnight at 4 °C. The samples were cut into 20-μm-thick sections using a cryostat (CM1900, Leica, Wiesbaden, Germany), washed in PBS for three cycles of 5 min each, penetrated with 0.1% TritonX-100 for 15 min, and blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin for 1 h at room temperature. To determine the extent of astrogliosis, sections from each group (three samples in each group) were incubated with the primary antibody against GFAP (astrocyte biomarker, 1:500, 04-1062, Merck Millipore) for 48 h at 4 °C. Then the sections were washed with PBS (three times within 5 min each) and incubated with Fluoresceinisothiocyanate (FITC)-conjuguated donkey-anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:200, 711-095-152, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) for 2 h. To further identify the cell type expressing NF-κB in BCP rats, the sections were co-cultured by the primary antibodies NF-κB p65 (1:100, MAB3026, Merck Millipore) with GFAP (1:500), Iba1 (microglia biomarker, 1:200, ab5067, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), or NeuN (neuronal biomarker, 1:200, ABN78, Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). Second antibodies used were Cyanine CyTM3-conjugated donkey-anti-mouse Ig (1:300, 715-165-150, Jackson ImmunoResearch), Fluorescein (FITC)-conjugated donkey-anti-goat Ig (1:200, 705-095-003, Jackson ImmunoResearch) and Fluorescein (FITC)-conjugated donkey-anti-rabbit Ig (1:200, 711-095-152, Jackson ImmunoResearch). After being washed three times with PBS, sections were mounted in Fluoromount-G solution (0100-01, SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL, USA). Images were captured using a Leica fluorescence microscope (DM2500, Mannheim, Germany).

Primary astrocyte cultures and immunocytochemistry

Primary astrocytes, prepared from the cerebral cortex of neonatal rats (12–24 h old), were cultured in medium that contained 10% fetal bovine serum in low-glucose Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium. The cells were adjusted to a density of 2.5×105 cells/cm2 and were cultured at 37 °C in 95% air/5% CO2. The culture medium was replaced every 72 h. Recombinant rat interleukin-1 beta (rrIL-1β) obtained from PeproTech (400-01B, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) was used to induce NF-κB activation. After the cells had been cultured for 10 d and reached approximately 80% confluence, the rrIL-1β was added to the medium at different concentrations (0.1, 1.0, 10.0, and 50.0 ng/mL). To examine the inhibitory effect of minocycline, the cells were pretreated with this drug (25, 50, 75, and 100 μmol/mL) 12 h prior to rrIL-1β stimulation. Four hours after rrIL-1β interference, the astrocytes were fixed with 4% PFA for 20 min. Fluorescence triple staining with NF-κB p65 (1:100), GFAP (1:500), and 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; 1:10000, D9654, Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) was performed. Cyanine CyTM3-conjugated secondary antibody (1:300) and FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (1:200) were incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The percentage of NF-κB-positive nuclei was calculated from five microscopic fields per coverslip.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 17.0 (Chicago, IL, USA). All data are presented as the mean±standard error of the mean (SEM). The differences were evaluated based on unpaired Student's t-test for the comparison of two groups or one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) for multiple comparisons followed by Bonferroni or Dunnett's T3 tests if necessary. The differences in the PWT data between the groups were analyzed via two-way ANOVA, in which “Time” was treated as the “within subjects” factor and “Treatment” was treated as the “between subjects” factor, followed by a Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc test. A value of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Transplantation of Walker 256 mammary carcinoma cells induced bone destruction and mechanical tactile allodynia

The tibial histological staining showed the bone structure and the invaded carcinoma cells (Figure 2A, B). In the sham rats, the microgram indicated a normal structure; specifically, a clear border of the trabecular bone was identified, which was filled with bone marrow cells. In contrast, a robust destruction of the tibial bone was identified on the ipsilateral side in the BCP rats, with the bone marrow cells replaced by sarcoma cells; thus, a healthy trabecular structure was not detected. Therefore, the histological results clearly demonstrated that the transplantation of carcinoma cells induced bone destruction. Furthermore, all animals were tested for mechanical allodynia before and on d 3, 7, and 14 after the operation. On d 7 and 14, the PWT of the BCP animals decreased to 5.27±1.37 g and 1.33±0.38 g, respectively (P<0.05 vs sham), which indicated that mechanical tactile allodynia had developed (Figure 2C). Collectively, the BCP rat models were successfully established after Walker 256 mammary carcinoma cell inoculation.

Transplantation of Walker 256 mammary carcinoma cells induced bone destruction. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining showed a healthy bone structure in the sham surgery group. (B) In the BCP group, normal bone marrow cells were replaced by sarcoma, and the healthy trabecular structure was degraded and disorganized. Scale bars=200 μm. (C) The paw withdrawal threshold (PWT) was not reduced in the sham group; however, it was significantly decreased in the BCP group. *P<0.05 vs sham at 7 d, #P<0.05 vs sham at 14 d.

Effects of minocycline on the expression level of spinal GFAP and PSD95 in response to BCP

Analysis of GFAP level indicated that GFAP was significantly up-regulated in the BCP rats (P<0.05 vs sham; Figure 3A, C). As shown in Figure 3I and K, the number of astrocytes (GFAP positive) calculated from lamina I to III was robustly increased in the BCP group (P<0.01 vs sham); moreover, the astrocytes exhibited profound proliferation and hypertrophy and had increased the podocytic processes. Furthermore, PSD95 plays a pivotal role in the stability, strength, and plasticity of synapses. To characterize the influence of Walker 256 mammary carcinoma cell inoculation on spinal neurons, the mean relative expression level of spinal PSD95 was also determined via Western blot analyses. PSD95 was increased in the rat models of BCP (Figure 3A, B; P<0.01). An up-regulation of GFAP and PSD95 indicated the development of astrogliosis and synaptic plasticity.

Minocycline reversed the up-regulation of GFAP and PSD95. GFAP and PSD95 were significantly increased in the rats with BCP (A, B, and C). Minocycline reversed the up-regulation of GFAP and PSD95 in the ip injection group (D, E, and F). At superficial of the spinal dorsal horn (from lamina I to III), GFAP-positive cells were increased in the BCP rats; however, these cells were significantly decreased by minocycline ip injection at a dose of 80 mg/kg. Scale bars=200 μm. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs sham; #P<0.05 vs vehicle ip; $$P<0.01 vs BCP.

To examine the effects of minocycline on spinal astrocytes and neurons, the BCP rats were treated with either minocycline or vehicle according to our experimental protocol. The results indicated that the level of GFAP was significantly decreased in the high dose minocycline-treated BCP rats (80 mg/kg ip, P<0.05 vs vehicle; Figure 3D, F). Moreover, the immunohistochemistry results demonstrated that the GFAP expression was significantly decreased (Figure 3J, K, P<0.05 vs BCP). Furthermore, minocycline diminished the expression level of PSD95 compared with the vehicle-treated rats (80 mg/kg ip, P<0.05 vs vehicle; Figure 3D, E), which indicated that minocycline has the ability to reverse astrogliosis and synaptic plasticity.

Effects of minocycline on mechanical allodynia induced by the BCP

Astrogliosis is involved in the maintenance of pain; thus, inhibiting astrocytes may ameliorate BCP-related pain behavior. Therefore, the PWT was assessed to evaluate the effects of minocycline on pain relief. As shown in Figure 4, the PWT value in the minocycline-treated rats was increased compared with the PWT value in the vehicle-treated control rats. On d 3, minocycline significantly increased the PWT both in the intrathecal injection and ip injection groups (100 μg intrathecal, P<0.05 vs vehicle; 80 mg/kg ip, P<0.05 vs vehicle). This finding suggests that minocycline ameliorates BCP-related pain behavior.

Minocycline reversed mechanical tactile allodynia. Minocycline (100 μg intrathecal injection group, 40 mg/kg and 80 mg/kg ip injection group) dramatically reversed tactile allodynia after three days of consecutive injections. *P<0.05 vs vehicle intrathecal, #P<0.05 vs vehicle ip. PWT, paw withdrawal threshold.

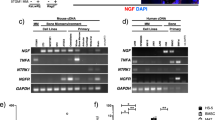

Effects of minocycline on the expression of spinal NF-κB in response to BCP and its translocation in cultured primary astrocytes induced by rrIL-1β stimulation

NF-κB is known to be an important transcriptional factor involved in the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Inactive NF-κB is present in the cytosol; however, it translocates to the nucleus when activated. Therefore, quantitative analyses of both the total and nucleus levels of NF-κB p65 subunits were performed using Western blots. The results demonstrated that NF-κB was robustly increased in the BCP group compared with the sham animals (Figure 5A, B; P<0.05). Furthermore, the co-expression of NF-κB with GFAP, NeuN, and Iba1 in the spinal dorsal horn was examined via immunofluorescence staining (Figure 5C, D, and E). The results indicated that NF-κB was co-localized with astrocyte markers, but not with microglial or neuronal markers. To determine whether minocycline suppresses the activation of NF-κB, the drug was administered on d 14 after tumor cell inoculation. After three consecutive days of treatment, both the total and nucleus levels of NF-κB p65 were down-regulated, especially when systemically treated with a high dose of minocycline (80 mg/kg ip, P<0.05 vs vehicle; Figure 5F, G).

Minocycline inhibited NF-κB activation. In the rat models of BCP, both the total and nucleus levels of NF-κB were increased (A, B). Immunohistochemistry staining indicated that NF-κB was co-localized with GFAP, but not with NeuN or Iba1 (C, D, and E). Scale bars=50 μm. Following the repeated administration of minocycline, both the total and nuclear expressions of NF-κB were inhibited (F, G). Cultured primary astrocytes were stimulated with rrIL-1β at concentrations of 0.1, 1.0, 10, and 50.0 ng/mL for 4 h. NF-κB was significantly activated as measured by the percentage of NF-κB-positive nuclei (H); however, the translocation was dose-dependently inhibited by minocycline (I). Scale bars=200 μm. *P<0.05 vs sham, #P<0.05 vs vehicle ip, $P<0.05 vs control.

To determine whether minocycline suppresses the translocation of NF-κB in vitro, primary astrocytes were cultured and stimulated by rrIL-1β at concentrations of 0.1, 1.0, 10, and 50.0 ng/mL. Immunofluorescence analyses indicated that the p65 subunit of NF-κB significantly translocated to the nucleus following the administration of 10.0 and 50.0 ng/mL of rrIL-1β compared with the control (41.8%±7.1% and 41.1%±3.5% vs 18.9%±2.6%, P<0.05; Figure 5H). Furthermore, primary astrocytes pretreated with minocycline 12 h prior to stimulation with 10 ng/mL rrIL-1β markedly inhibited the translocation of NF-κB at the concentrations of 75 and 100 μmol/L compared with the control group (23.8%±3.1% and 21.1%±6.1% vs 40.6%±5.4%, P<0.05; Figure 5I). These findings indicate that minocycline inhibits the NF-κB signaling pathway in vitro.

Effects of minocycline on the expression of spinal p-IKKα and IκBα in response to BCP

To further investigate the effect of minocycline on the NF-κB signaling pathway, p-IKKα and IκBα were subsequently examined. The expression level of p-IKKα was remarkably increased in the rat models of BCP (Figure 6A, C; P<0.05); however, it was distinctively inhibited by minocycline, with the exception of the 50 μg intrathecal injection group (100 μg intrathecal, P<0.05 vs vehicle intrathecal; 40 mg/kg and 80 mg/kg ip, P<0.05 vs vehicle ip; Figure 6D, F). Interestingly, IκBα was not down-regulated canonically in the BCP group (Figure 6A, B). Nevertheless, IκBα was significantly decreased in the 80 mg/kg ip minocycline-treated group (80 mg/kg ip, P<0.05 vs vehicle; Figure 6D, E).

Minocycline inhibited IκBα and p-IKKα. BCP had no influence on IκBα; however, it increased p-IKKα (A, B, and C). Repeated administration of minocycline inhibited IκBα and p-IKKα (D, E, and F). *P<0.05 vs sham, #P<0.05 vs vehicle ip, $P<0.05 vs vehicle intrathecal.

Discussion

This study provides pharmacological evidence that the anti-nociceptive effects of minocycline in the spinal cords of BCP rats are attributed to the suppression of astrogliosis and neural plasticity. Further investigation using in vivo and in vitro experiments indicates that inhibition of the NF-κB signaling pathway may represent one mechanism by which minocycline alleviates mechanical allodynia underlying BCP conditions.

BCP induced by Walker 256 mammary carcinoma cell inoculation

Over the previous few years, BCP models have been developed with various cell lines, animals, and injection sites, and these models have been systematically reviewed by Currie et al5. Based on previous literature5,9,23,25,30,31, Walker 256 mammary carcinoma cell inoculation has been demonstrated to be a successful model to investigate BCP because it effectively mimics the chronic pain symptoms of patients who suffer from osteocarcinoma. Here, the tumor-bearing rats manifested mechanical tactile allodynia 14 d after tumor cell inoculation. Moreover, paraffin histological micrograms indicated evidence of tumor growth and bone destruction. Therefore, our BCP model was consistent with the common signs and symptoms present in patients with BCP.

Astrogliosis and up-regulation of synaptic plasticity in the spinal cord in a rat model of BCP

Astrocytes have an intimate relationship with neurons in the central nervous system (CNS). Specifically, astrocytes have contact with neuronal somata, dendrites, and enwrap synapses32, provide metabolic substrates for neurons, stabilize the extracellular ionic environment and pH, and are involved in the uptake of neurotransmitters and the maintenance of the blood-brain barrier33. Under BCP conditions, astrocytes become reactive, and this alters their morphology and increases GFAP expression. Activated astrocytes release a range of pro-inflammatory cytokines (eg, IL-1β) and chemokines (eg, CXCL1), which thus induces neuronal sensitization7,34,35,36,37. Nevertheless, astrocytes also express receptors for these cytokines, and a positive feedback loop is consequently established. The interaction between activated astrocytes and sensitized neurons contributes to central sensitization38,39,40. The concept of “functional islands of synapses” highlights the vital roles astrocytes play in the modulation of neuronal function by synchronizing neuronal firing and coordinating synaptic networks41. A study using mice demonstrated that the activation of astrocytes, but not microglia, was a prerequisite in two types of cancer-induced pain models42. Therefore, reactive astrocytes play a crucial role in BCP. As a core event of BCP, synaptic plasticity is dependent on glutamatergic receptors and the scaffolding protein PSD95. The current findings demonstrated that both spinal GFAP and PSD95 were dramatically increased in rats with BCP compared with sham rats, which indicates that astrogliosis and synaptic plasticity had developed. Interestingly, a recent study reported that both microglia and astrocytes were unnecessary for BCP43. We speculate that this discrepancy may be a result of differences in the inoculated carcinoma cell lines and experimental animal species; however, further study is required to clarify this intriguing issue.

Minocycline attenuates BCP by inhibiting astrogliosis and neural plasticity

Minocycline is often considered an inhibitor of microglia27. A preclinical study of BCP indicated that the drug only attenuated pain behavior at an early stage (from d 4 to d 6) by inhibiting microglia44; however, an increasing number of therapeutic effects of the agent have been identified. In studies of CIPN, minocycline prevented CIPN-related symptoms and the activation of astrocytes despite the lack of microglial activation indicators16,17,18,19. Nevertheless, minocycline also possesses neuroprotective roles20,28,45,46. One notable characteristic of minocycline is that it has a direct effect on sodium channels in primary afferent neurons47, which suggests it has a role of peripheral analgesia. Based on these previous findings, we designed the present study to identify the effects of minocycline on spinal astrocytes at a later stage (from d 14 to d 16) of BCP. Following the administration of minocycline (twice per day for 3 d), both GFAP and PSD95 were down-regulated, and tactile allodynia was alleviated. Therefore, the ability of minocycline to alleviate BCP may be ascribed, at least in part, to a reduction in both astrogliosis and synaptic plasticity. Interestingly, the suppressive effects of minocycline were more profound in conditions with a high dose of minocycline administered via intraperitoneal injection. Consistent with the known pathogenesis of BCP, peripheral sensitization, induced by releasing algogenic substances from cancer/stromal cells, is one important contributor48. We speculate that the relatively powerful effects of systemic minocycline should be attributed to its peripheral actions, such as anti-inflammation49, and not only its role as a glial attenuator in the CNS.

NF-κB is activated in spinal astrocytes of BCP rats and facilitates pain perception

Under basal conditions, NF-κB is a dimer of proteins that binds to the inhibitory protein IκB and is present in the cytosol in a latent form. The major subunits of NF-κB in astrocytes are p65 and p5050. When stimulated by appropriate signals, trimeric IKK is activated and phosphorylates IκB, which leads to its ubiquitination and degradation51. The liberated reactive NF-κB translocates to the nucleus and targets specific genes that are involved in chronic pain10,14,52,53. The algogenic effect of NF-κB has also been identified in BCP animals. We demonstrated that NF-κB was specifically co-localized with astrocytes in the spinal cord of BCP rats, which is consistent with previous literature. For example, Xu et al8 reported that NF-κB contributed to BCP via the mediation of CXCL1 production in spinal astrocytes; these authors also highlighted that an intrathecally injected inhibitor of NF-κB significantly attenuated nociceptive behavior. Similarly, other studies based on neuropathic pain have demonstrated that targeted blockades of NF-κB in the spinal cord alleviated pain perception13,15. Furthermore, it has also been identified that NF-κB mediated inflammatory pain in mice via chemokine production in spinal astrocytes14. In the present study, we extended the role of NF-κB in BCP rat models induced by inoculating Walker 256 mammary carcinoma cells and demonstrated that it was robustly increased in spinal astrocytes. To further understand the underlying mechanisms of NF-κB activation, we examined the upstream proteins, the catalytic subunits IKKα and the inhibitory protein IκBα. Consistent with our assumption, IKKα was phosphorylated in rats with BCP. In contrast, IκBα was not down-regulated in BCP animals, which led us to postulate that a self-recovery mechanism may be involved. Taken together, these findings suggest that NF-κB signaling is activated under BCP conditions, and its potential role is facilitating pain perception.

Minocycline attenuates BCP via NF-κB inhibition

Our work also demonstrated that the administration of minocycline inhibited NF-κB signaling under the BCP condition. NF-κB facilitates pain perception; thus, the suppression of its activation may represent a potential therapeutic strategy for BCP. Emerging evidence indicates that minocycline down-regulates NF-κB activity21,54,55; thus, we speculate that minocycline alleviates BCP by inhibiting NF-κB signaling. Consistent with our hypothesis, the drug significantly decreased both the total and nuclear expression levels of NF-κB in the spinal cord of BCP rats, as well as p-IKKα. Notably, IκBα was not changed by minocycline administration with the exception of the high-dose ip injection group. These unexpected results may be a result of the complicated modulation in vivo, and we suggest that the decrease in IκBα may be related, in part, to the down-regulation of total NF-κB. This intriguing finding will be investigated in the future. Furthermore, an effect of minocycline on NF-κB translocation was identified in primary astrocytes. The pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β is a major inducer of astrogliosis via the NF-κB signaling pathway30,56,57; thus, cultured cells were stimulated by rrIL-1β for 4 h. The NF-κB p65 subunit translocated to the nucleus; however, the translocation was dose-dependently inhibited when pretreated with minocycline. Our in vitro study also confirmed that minocycline inhibits the NF-κB signaling pathway. The mechanisms for these inhibitory effects are as follows: 1) minocycline inhibited NF-κB activation potentially through a reduction in IL-1β signaling54, which serves as a stimulus for NF-κB58,59; 2) minocycline down-regulated NF-κB activity, in part, via the inhibition of transforming growth factor beta 121; and 3) minocycline down-regulated acetylated H3K18 that was bound to the promoters of tumor necrosis factor alpha, which contains an NF-κB binding site55. Collectively, the current and previous results suggest that minocycline inhibits NF-κB activation.

Perspectives

As demonstrated in other studies, Walker 256 mammary carcinoma cell inoculation induces robust spinal neuroinflammation7 and activates astrocytes that release pro-inflammatory cytokines in the spinal cord to enhance and prolong a persistent pain state36,60,61. It is reasonable to argue that a complex neuroinflammatory mechanism is involved in BCP. Similar to other tetracyclines, minocycline acts as an antibiotic; however, it has unusual anti-inflammatory properties and easily permeates the blood-brain barrier. It is also important to note that the systemic treatment of minocycline was more effective than the intrathecal injection. We speculate that minocycline may act through a global anti-inflammatory mechanism, which may not be restricted to the spinal cord; however, this finding should be investigated in the future. Taken together, our findings suggest that minocycline may be a valid and viable therapeutic drug for BCP.

Conclusion

In summary, our study demonstrated that the inoculation of Walker 256 mammary carcinoma cells contributed to a persistent BCP state. This pernicious effect was attenuated by minocycline administration, which suppressed spinal astrogliosis and neuronal plasticity. Additional experiments identified that minocycline inhibits the NF-κB signaling pathway in astrocytes. Based on the current findings, minocycline may represent a potential therapeutic drug for BCP.

Author contribution

Zhen-peng SONG designed the experiment and performed the animal surgery and behavioral testing; Anne MANYANDE wrote the paper; Bing-rui XIONG and Ya-qun ZHOU carried out the cell culture, immunohistochemistry, and Western blotting analyses; Xue-hai GUAN and Fei CAO analyzed the data; Hua ZHENG participated in the animal surgery and behavior testing; Yu-ke TIAN conceived the project, coordinated and supervised the experiments, and revised the manuscript.

References

Yanagisawa Y, Furue H, Kawamata T, Uta D, Yamamoto J, Furuse S, et al. Bone cancer induces a unique central sensitization through synaptic changes in a wide area of the spinal cord. Mol Pain 2010; 6: 38.

Portenoy RK, Payne D, Jacobsen P . Breakthrough pain: characteristics and impact in patients with cancer pain. Pain 1999; 81: 129–34.

Mantyh PW . A mechanism based understanding of cancer pain. Pain 2002; 96: 1–2.

Mantyh PW . Cancer pain and its impact on diagnosis, survival and quality of life. Nat Rev Neurosci 2006; 7: 797–809.

Currie GL, Delaney A, Bennett MI, Dickenson AH, Egan KJ, Vesterinen HM, et al. Animal models of bone cancer pain: systematic review and meta-analyses. Pain 2013; 154: 917–26.

Ren BX, Gu XP, Zheng YG, Liu CL, Wang D, Sun YE, et al. Intrathecal injection of metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 3 and 5 agonist/antagonist attenuates bone cancer pain by inhibition of spinal astrocyte activation in a mouse model. Anesthesiology 2012; 116: 122–32.

Mao-Ying QL, Wang XW, Yang CJ, Li X, Mi WL, Wu GC, et al. Robust spinal neuroinflammation mediates mechanical allodynia in Walker 256 induced bone cancer rats. Mol Brain 2012; 5: 16.

Xu J, Zhu MD, Zhang X, Tian H, Zhang JH, Wu XB, et al. NFkappaB-mediated CXCL1 production in spinal cord astrocytes contributes to the maintenance of bone cancer pain in mice. J Neuroinflammation 2014; 11: 38.

Bu H, Shu B, Gao F, Liu C, Guan X, Ke C, et al. Spinal IFN-gamma-induced protein-10 (CXCL10) mediates metastatic breast cancer-induced bone pain by activation of microglia in rat models. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2014; 143: 255–63.

Dai ZK, Lin TC, Liou JC, Cheng KI, Chen JY, Chu LW, et al. Xanthine derivative KMUP-1 reduces inflammation and hyperalgesia in a bilateral chronic constriction injury model by suppressing MAPK and NFkappaB activation. Mol Pharm 2014; 11: 1621–31.

Liu ZN, Zhao M, Zheng Q, Zhao HY, Hou WJ, Bai SL . Inhibitory effects of rosiglitazone on paraquat-induced acute lung injury in rats. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2013; 34: 1317–24.

Lee MK, Han SR, Park MK, Kim MJ, Bae YC, Kim SK, et al. Behavioral evidence for the differential regulation of p-p38 MAPK and p-NF-kappaB in rats with trigeminal neuropathic pain. Mol Pain 2011; 7: 57.

Zhou C, Shi X, Huang H, Zhu Y, Wu Y . Montelukast attenuates neuropathic pain through inhibiting p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and nuclear factor-kappa B in a rat model of chronic constriction injury. Anesth Analg 2014; 118: 1090–6.

Zhao LX, Jiang BC, Wu XB, Cao DL, Gao YJ . Ligustilide attenuates inflammatory pain via inhibition of NFkappaB-mediated chemokines production in spinal astrocytes. Eur J Neurosci 2014; 39: 1391–402.

Meunier A, Latremoliere A, Dominguez E, Mauborgne A, Philippe S, Hamon M, et al. Lentiviral-mediated targeted NF-kappaB blockade in dorsal spinal cord glia attenuates sciatic nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain in the rat. Mol Ther 2007; 15: 687–97.

Cata JP, Weng HR, Dougherty PM . The effects of thalidomide and minocycline on taxol-induced hyperalgesia in rats. Brain Res 2008; 1229: 100–10.

Boyette-Davis J, Xin W, Zhang H, Dougherty PM . Intraepidermal nerve fiber loss corresponds to the development of taxol-induced hyperalgesia and can be prevented by treatment with minocycline. Pain 2011; 152: 308–13.

Boyette-Davis J, Dougherty PM . Protection against oxaliplatin-induced mechanical hyperalgesia and intraepidermal nerve fiber loss by minocycline. Exp Neurol 2011; 229: 353–7.

Robinson CR, Zhang H, Dougherty PM . Astrocytes, but not microglia, are activated in oxaliplatin and bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy in the rat. Neuroscience 2014; 274: 308–17.

Jin WJ, Feng SW, Feng Z, Lu SM, Qi T, Qian YN . Minocycline improves postoperative cognitive impairment in aged mice by inhibiting astrocytic activation. Neuroreport 2014; 25: 1–6.

Ataie-Kachoie P, Badar S, Morris DL, Pourgholami MH . Minocycline targets the NF-kappaB Nexus through suppression of TGF-beta1-TAK1-IkappaB signaling in ovarian cancer. Mol Cancer Res 2013; 11: 1279–91.

Ke C, Li C, Huang X, Cao F, Shi D, He W, et al. Protocadherin20 promotes excitatory synaptogenesis in dorsal horn and contributes to bone cancer pain. Neuropharmacology 2013; 75: 181–90.

Guan XH, Fu QC, Shi D, Bu HL, Song ZP, Xiong BR, et al. Activation of spinal chemokine receptor CXCR3 mediates bone cancer pain through an Akt-ERK crosstalk pathway in rats. Exp Neurol 2015; 263: 39–49.

Liu X, Bu H, Liu C, Gao F, Yang H, Tian X, et al. Inhibition of glial activation in rostral ventromedial medulla attenuates mechanical allodynia in a rat model of cancer-induced bone pain. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci 2012; 32: 291–8.

Ke CB, He WS, Li CJ, Shi D, Gao F, Tian YK . Enhanced SCN7A/Nax expression contributes to bone cancer pain by increasing excitability of neurons in dorsal root ganglion. Neuroscience 2012; 227: 80–9.

Guan X, Fu Q, Xiong B, Song Z, Shu B, Bu H, et al. Activation of PI3Kgamma/Akt pathway mediates bone cancer pain in rats. J Neurochem 2015; 134: 590–600.

Padi SS, Kulkarni SK . Minocycline prevents the development of neuropathic pain, but not acute pain: possible anti-inflammatory and antioxidant mechanisms. Eur J Pharmacol 2008; 601: 79–87.

Adembri C, Selmi V, Vitali L, Tani A, Margheri M, Loriga B, et al. Minocycline but not tigecycline is neuroprotective and reduces the neuroinflammatory response induced by the superimposition of sepsis upon traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Med 2014; 42: e570–82.

Wang LN, Yang JP, Zhan Y, Ji FH, Wang XY, Zuo JL, et al. Minocycline-induced reduction of brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression in relation to cancer-induced bone pain in rats. J Neurosci Res 2012; 90: 672–81.

Wang LX, Wang ZJ . Animal and cellular models of chronic pain. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2003; 55: 949–65.

Brigatte P, Sampaio SC, Gutierrez VP, Guerra JL, Sinhorini IL, Curi R, et al. Walker 256 tumor-bearing rats as a model to study cancer pain. J Pain 2007; 8: 412–21.

Hansen RR, Malcangio M . Astrocytes--multitaskers in chronic pain. Eur J Pharmacol 2013; 716: 120–8.

Sticozzi C, Belmonte G, Meini A, Carbotti P, Grasso G, Palmi M . IL-1beta induces GFAP expression in vitro and in vivo and protects neurons from traumatic injury-associated apoptosis in rat brain striatum via NFkappaB/Ca(2)(+)-calmodulin/ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. Neuroscience 2013; 252: 367–83.

Kawasaki Y, Zhang L, Cheng JK, Ji RR . Cytokine mechanisms of central sensitization: distinct and overlapping role of interleukin-1beta, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in regulating synaptic and neuronal activity in the superficial spinal cord. J Neurosci 2008; 28: 5189–94.

Zhou YQ, Gao HY, Guan XH, Yuan X, Fang GG, Chen Y, et al. Chemokines and their receptors: potential therapeutic targets for bone cancer pain. Curr Pharm Des 2015; 21: 5029–33.

Ye D, Bu H, Guo G, Shu B, Wang W, Guan X, et al. Activation of CXCL10/CXCR3 signaling attenuates morphine analgesia: involvement of Gi protein. J Mol Neurosci 2014; 53: 571–9.

Guo G, Gao F . CXCR3: latest evidence for the involvement of chemokine signaling in bone cancer pain. Exp Neurol 2015; 265: 176–9.

Old EA, Malcangio M . Chemokine mediated neuron-glia communication and aberrant signalling in neuropathic pain states. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2012; 12: 67–73.

Gao YJ, Ji RR . Targeting astrocyte signaling for chronic pain. Neurotherapeutics 2010; 7: 482–93.

Fellin T . Communication between neurons and astrocytes: relevance to the modulation of synaptic and network activity. J Neurochem 2009; 108: 533–44.

Halassa MM, Fellin T, Takano H, Dong JH, Haydon PG . Synaptic islands defined by the territory of a single astrocyte. J Neurosci 2007; 27: 6473–7.

Hald A, Nedergaard S, Hansen RR, Ding M, Heegaard AM . Differential activation of spinal cord glial cells in murine models of neuropathic and cancer pain. Eur J Pain 2009; 13: 138–45.

Ducourneau VR, Dolique T, Hachem-Delaunay S, Miraucourt LS, Amadio A, Blaszczyk L, et al. Cancer pain is not necessarily correlated with spinal overexpression of reactive glia markers. Pain 2014; 155: 275–91.

Ding JJ, Zhang YJ, Jiao Z, Wang Y . The effect of poor compliance on the pharmacokinetics of carbamazepine and its epoxide metabolite using Monte Carlo simulation. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2012; 33: 1431–40.

Kong F, Chen S, Cheng Y, Ma L, Lu H, Zhang H, et al. Minocycline attenuates cognitive impairment induced by isoflurane anesthesia in aged rats. PLoS One 2013; 8: e61385.

Choi Y, Kim HS, Shin KY, Kim EM, Kim M, Kim HS, et al. Minocycline attenuates neuronal cell death and improves cognitive impairment in Alzheimer's disease models. Neuropsychopharmacology 2007; 32: 2393–404.

Kim TH, Kim HI, Kim J, Park M, Song JH . Effects of minocycline on Na+ currents in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Brain Res 2011; 1370: 34–42.

Mantyh P . Bone cancer pain: causes, consequences, and therapeutic opportunities. Pain 2013; 154 (Suppl 1): S54–62.

Ledeboer A, Sloane EM, Milligan ED, Frank MG, Mahony JH, Maier SF, et al. Minocycline attenuates mechanical allodynia and proinflammatory cytokine expression in rat models of pain facilitation. Pain 2005; 115: 71–83.

Rosenberger J, Petrovics G, Buzas B . Oxidative stress induces proorphanin FQ and proenkephalin gene expression in astrocytes through p38- and ERK-MAP kinases and NF-kappaB. J Neurochem 2001; 79: 35–44.

Vallabhapurapu S, Karin M . Regulation and function of NF-kappaB transcription factors in the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol 2009; 27: 693–733.

Jin XG, He SQ, Yan XT, Zhang G, Wan L, Wang J, et al. Variants of neural nitric oxide synthase in the spinal cord of neuropathic rats and their effects on nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-kappaB) activity in PC12 cells. J Pain 2009; 10: 80–9.

de Mos M, Laferriere A, Millecamps M, Pilkington M, Sturkenboom MC, Huygen FJ, et al. Role of NFkappaB in an animal model of complex regional pain syndrome-type I (CRPS-I). J Pain 2009; 10: 1161–9.

Orio L, Llopis N, Torres E, Izco M, O'Shea E, Colado MI . A study on the mechanisms by which minocycline protects against MDMA ('ecstasy')-induced neurotoxicity of 5-HT cortical neurons. Neurotox Res 2010; 18: 187–99.

Wang LL, Chen H, Huang K, Zheng L . Elevated histone acetylations in Muller cells contribute to inflammation: a novel inhibitory effect of minocycline. Glia 2012; 60: 1896–905.

Aktan F . iNOS-mediated nitric oxide production and its regulation. Life Sci 2004; 75: 639–53.

John GR, Lee SC, Brosnan CF . Cytokines: powerful regulators of glial cell activation. Neuroscientist 2003; 9: 10–22.

Mattson MP, Camandola S . NF-kappaB in neuronal plasticity and neurodegenerative disorders. J Clin Invest 2001; 107: 247–54.

Bowie A, O'Neill LA . Oxidative stress and nuclear factor-kappaB activation: a reassessment of the evidence in the light of recent discoveries. Biochem Pharmacol 2000; 59: 13–23.

Gosselin RD, Suter MR, Ji RR, Decosterd I . Glial cells and chronic pain. Neuroscientist 2010; 16: 519–31.

Cao F, Chen SS, Yan XF, Xiao XP, Liu XJ, Yang SB, et al. Evaluation of side effects through selective ablation of the mu opioid receptor expressing descending nociceptive facilitatory neurons in the rostral ventromedial medulla with dermorphin-saporin. Neurotoxicology 2009; 30: 1096–106.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No 81371250, 81400917 and 81571053) and the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (Grant No 2014CFB293).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Song, Zp., Xiong, Br., Guan, Xh. et al. Minocycline attenuates bone cancer pain in rats by inhibiting NF-κB in spinal astrocytes. Acta Pharmacol Sin 37, 753–762 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/aps.2016.1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/aps.2016.1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Astrocytes in Chronic Pain: Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms

Neuroscience Bulletin (2023)

-

Chemogenetic and Optogenetic Manipulations of Microglia in Chronic Pain

Neuroscience Bulletin (2023)

-

TRAF6 Contributes to CFA-Induced Spinal Microglial Activation and Chronic Inflammatory Pain in Mice

Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology (2022)

-

Sodium aescinate alleviates bone cancer pain in rats by suppressing microglial activation via p38 MAPK/c-Fos signaling

Molecular & Cellular Toxicology (2022)

-

Microglia induce the transformation of A1/A2 reactive astrocytes via the CXCR7/PI3K/Akt pathway in chronic post-surgical pain

Journal of Neuroinflammation (2020)