Abstract

Aim:

Tramadol is an atypical opioid analgesic with low potential for tolerance and addiction. However, its opioid activity is much lower than classic opiates such as morphine. To develop novel analgesic and further explore the structure activity relationship (SAR) of tramadol skeleton.

Methods:

Based on a three-dimensional (3D) structure superimposition and molecular docking study, we found that M1 (the active metabolite of tramadol) and morphine have common pharmacophore features and similar binding modes at the μ opioid receptor in which the substituents on the nitrogen atom of both compounds faced a common hydrophobic pocket formed by Trp2936.48 and Tyr3267.43. In this study, N-phenethylnormorphine was docked to the μ opioid receptor. It was found that the N-substituted group of N-phenethylnormorphine extended into a hydrophobic pocket formed by Trp2936.48 and Tyr3267.43. This hydrophobic interaction may contribute to the improvement of its opioid activities as compared with morphine. The binding modes of M1, morphine and N-phenethylnormorphine overlapped, indicating that the substituent on the nitrogen atoms of the three compounds may adopt common orientations. A series of N-phenylalkyl derivatives from the tramadol scaffold were designed, synthesized and assayed in order to generate a new type of analgesics.

Results:

As a result, compound 5b was identified to be an active candidate from these compounds. Furthermore, the binding modes of 5b and morphine derivatives in the μ opioid receptor were comparatively studied.

Conclusion:

Unlike morphine-derived structures in which bulky N-substitution is associated with improved opioid-like activities, there seems to be a different story for tramadol, suggesting the potential difference of SAR between these compounds. A new type of interaction mechanism in tramadol analogue (5b) was discovered, which will help advance potent tramadol-based analgesic design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

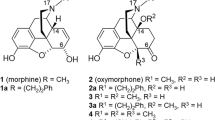

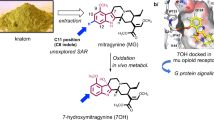

Opioids are narcotic analgesics widely prescribed to relieve moderate-to-severe pains and most of these agents exert their opioid-like effects through opioid receptors (eg, μ, δ, κ, and ORL1 receptors). However, most clinically used analgesics are restricted to μ opioid agonists, which are associated with respiratory depression, constipation, addiction, physical dependence and other notorious adverse effects. Tramadol, which was launched in 1977, is a fully synthetic opioid pain medication used to treat moderate to severe pain, both acute and chronic1. In addition, it has also been used to treat depression, postherpetic neuralgia, diabetic neuropathy premature ejaculation2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Tramadol displays some weak side effects, including nausea, dizziness, indigestion and abdominal pain in individual patients9,10. It was identified to be an atypical opioid, both structurally and pharmacologically. It acts as a weak μ opioid receptor agonist and serotonin reuptake and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor11,12. Its O-desmethyl metabolite (M1) is much more potent on the μ opioid receptor13 (Figure 1). However, few studies on structure and activity relationship of tramadol analogues and the binding mode between tramadol analogues and μ opioid receptor were performed. In this study, we designed a series of N-phenylalkyl substituted tramadol derivatives to explore their structure activity relationship for developing novel opioid analgesics and comparatively discussed the difference in binding modes of these compounds and morphine derivatives.

Structure of (±)-tramadol 1, metabolite (±)-M1, codeine, and morphine.

Materials and methods

Experimental section

All chemicals and solvents were supplied by Tansoole and were used without further purification. 1H and 3C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AMX-400 instrument. Proton-coupling patterns were described as singlet, doublet, triplet, quartet, multiplet, and broad. Mass spectra were generated with electric ionization (ESI) produced by an HP5973N analytical mass spectrometer. High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) spectra were recorded with an AB 5600+ Q TOF instrument.

General procedure for the syntheses of N-methyl-N-phenylalkylaminomethyl-cyclohexanones (3a–3d)

A mixture of cyclohexanone (1 g, 1.06 mmol), N-methylphenylalkyl-amine (1.06 mmol) and 1/5th of paraformaldehyde (2 mmol) in isopropanol (20 mL) was stirred and concentrated HCl was added drop-wise to adjust the solution to pH 4. The reaction mixture was then heated in an oil bath at 90–95 °C for 30 min with stirring. The other four portions of paraformaldehyde were added at 15 min intervals. The reaction mixture was further refluxed for 4 h and the solvent was distilled off. The residues were washed with hexane, adjusted to an alkaline pH with a sodium bicarbonate solution and extracted with ethyl acetate. Combined organic extracts were dried over Na2SO4 and distilled to afford the Mannich bases (3a–3d) in good yield.

General procedure of the Grignard reaction for the preparation of 4a–4d

A 100-mL, three-necked, round-bottomed flask equipped with a magnetic stirring bar, dropping funnel and reflux condenser was charged with magnesium chips (5 mmol) and iodine (5 mg) under argon. Anhydrous tetrahydrofuran (THF, 15 mL) was added into the reaction with a syringe. When the mixture was heated to 70 °C, 3-bromoanisole (5 mmol) solved in anhydrous THF was added drop-wise to the mixture. After all the magnesium chips were solved, the reaction was cooled to room temperature. Then, the Mannich base (3a–3d) (1 mmol) solved in anhydrous THF was added drop-wise to the reaction. After stirring for 3 h, the reaction was quenched with a saturated NH4Cl aqueous solution. The mixture was diluted with water and extracted with CHCl3 (3×15 mL). Combined organic extracts were dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, filtered, and evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified with column chromatography on silica gel using CH2Cl2/MeOH (20:1) to yield a yellow solid (4a–4d). The base (4a–4d) was transformed into hydrochlorides in diethylether by adding HCl in diethylether.

General procedure for the preparation of (5a–5d)

A solution of (4a–4d) (0.59 mmol) in anhydrous DCM (15 mL) was cooled to −40 °C. Boron tri-bromide in DCM (1.5 mmol) was added drop-wise into the solution. After being stirred for 1 h, the reaction mixture was allowed to adjust to room temperature. The reaction mixture was quenched by the addition of drops of ice-cold water. After dilution with water, the crude product was extracted with CHCl3 (3×15 mL). Combined organic extracts were dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, filtered, and evaporated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by column chromatography over silica using CH2Cl2/MeOH (20:1) to yield yellow oil (5a–5d). The base (5a–5d) was transformed into hydrochlorides in diethylether by adding HCl in diethylether.

2-{[Benzyl(methyl)amino]methyl}-1-(3-methoxyphenyl)cyclohexanol-HCl (4a)

White powder, 55 mg 47% 1H NMR (400 MHz, d6-DMSO) δ 10.18 (s, 1H), 7.62–7.53 (m, 1H), 7.47–7.19 (m, 5H), 7.04 (d, J=7.9 Hz, 2H), 6.86–6.72 (m, 1H), 5.06 (d, J=46.2 Hz, 1H), 4.20 (ddd, J=31.9, 13.0, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 3.93 (ddd, J=18.3, 13.0, 6.1 Hz, 1H), 3.76 (d, J=7.1 Hz, 3H), 2.84–2.61 (m, 1H), 2.47–2.27 (m, 4H), 2.25–2.02 (m, 2H), 1.89–1.07 (m, 7H) ppm. 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO) δ 159.61, 150.36, 131.85, 131.61, 130.79, 129.81, 129.53, 129.11, 128.95, 117.71, 112.04, 74.44, 60.26, 57.57, 56.78, 55.46, 42.23, 26.64, 24.89, 21.55. ESI-MS m/z 340.2 [M+H]+ HRMS m/z calculated for C22H30NO2 [M+H]+, 340.2271; observed, 340.2281.

2-{[Methyl(phenethyl)amino]methyl}-1-(3-methoxyphenyl)-cyclohexanol-HCl (4b)

White powder 27 mg 36% 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 10.14 (d, J=32.5 Hz, 1H), 7.37–7.04 (m, 8H), 6.78 (t, J=6.4 Hz, 1H), 5.12 (s, 1H), 3.73 (d, J=18.1 Hz, 3H), 3.15–2.74 (m, 4H), 2.74–2.53 (m, 3H), 2.44 (dd, J=18.4, 8.9 Hz, 2H), 2.35–2.07 (m, 2H), 1.92–1.35 (m, 7H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO) δ 159.64, 150.44, 137.50, 137.19, 129.56, 129.14, 129.00, 127.22, 127.15, 117.80, 112.04, 74.54, 58.22, 55.45, 54.26, 42.54, 30.01, 28.58, 27.05, 25.02, 21.66. ESI-MS m/z 354.3 [M+H]+ HRMS m/ z calculated for C23H32NO2 [M+H]+, 354.2428; observed, 354.2438.

1-(3-Methoxyphenyl)-2-{[methyl(3-phenylpropyl)amino]methyl}cyclohexanol-HCl (4c)

White powder 100 mg 60% 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 10.07 (d, J=57.6 Hz, 1H), 7.36–7.01 (m, 8H), 6.85–6.66 (m, 1H), 5.10 (s, 1H), 3.74 (d, J=7.2 Hz, 3H), 2.84 (t, J=10.9 Hz, 2H), 2.68 (m, 1H), 2.54 (d, J=4.7 Hz, 2H), 2.49–2.43 (m, 2H), 2.43–2.31 (m, 2H), 2.29–2.02 (m, 2H), 1.89–1.27 (m, 9H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO) δ 159.64, 150.41, 140.94, 129.58, 128.82, 128.72, 128.49, 126.88, 126.56, 117.76, 111.72, 74.52, 57.10, 55.46, 52.56, 42.35, 32.16, 27.01, 25.56, 24.99, 23.73, 21.59. ESI-MS m/z 368.3 [M+H]+ HRMS m/z calculated for C24H34NO2 [M+H]+, 368.2584; observed, 368.2593.

1-(3-Methoxyphenyl)-2-{[methyl(4-phenylbutyl)amino]methyl}cyclohexanol-HCl (4d)

White powder 78 mg 67% 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 9.86 (d, J=74.2 Hz, 1H), 7.34–7.14 (m, 6H), 7.07 (dd, J=17.0, 9.9 Hz, 2H), 6.89–6.77 (m, 1H), 5.14 (dd, J=25.6, 7.9 Hz, 1H), 3.76 (d, J=1.9 Hz, 3H), 2.91–2.76 (m, 2H), 2.68 (dt, J=17.4, 11.8 Hz, 1H), 2.58–2.52 (m, 3H), 2.49–2.30 (m, 3H), 2.30–2.01 (m, 2H), 1.86–0.95 (m, 11H). 13C NMR (151 MHz, DMSO) δ 159.65, 150.43, 142.08, 140.32, 129.58, 128.77, 128.66, 126.88, 126.33, 117.87, 112.04, 74.43, 57.65, 57.09, 55.46, 52.73, 42.27, 34.93, 28.39, 27.12, 24.98, 23.47, 21.63. ESI-MS m/z 382.3 [M+H]+ HRMS m /z calculated for C25H36NO2 [M+H]+, 382.2741; observed, 382.2742.

3-{2-{[Benzyl(methyl)amino]methyl}-1-hydroxycyclohexyl}phenol-HCl (5a)

White powder 98 mg 49% 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 9.69 (s, 1H), 9.36 (d, J=13.1 Hz, 1H), 7.56–7.19 (m, 5H), 7.13 (dt, J=11.0, 7.9 Hz, 1H), 6.99–6.80 (m, 2H), 6.64 (ddd, J=18.3, 8.0, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 4.98 (d, J=43.5 Hz, 1H), 4.31–4.12 (m, 1H), 3.95 (ddd, J=18.5, 12.9, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 2.85–2.54 (m, 2H), 2.47–2.22 (m, 4H), 2.13–1.13 (m, 9H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 157.64, 150.10, 131.55, 129.90, 129.42, 129.19, 129.04, 115.99, 113.69, 112.80, 74.27, 60.37, 57.07, 56.60, 42.10, 29.47, 26.49, 24.95, 21.52. ESI-MS m/z 326.2 [M+H]+ HRMS m/z calculated for C21H28NO2 [M+H]+, 326.2115; observed, 326.2118.

3-{1-Hydroxy-2-{[methyl(phenethyl)amino]methyl}cyclohexyl}phenol-HCl (5b)

White powder 118 mg 57% 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 9.32 (s, 1H), 8.80 (d, J=58.1 Hz, 1H), 7.40–7.07 (m, 6H), 6.94 (d, J=12.7 Hz, 2H), 6.62 (d, J=7.2 Hz, 1H), 5.06 (s, 1H), 3.23–2.53 (m, 8H), 2.16 (s, 1H), 1.94–1.32 (m, 9H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 157.30, 151.79, 140.91, 129.05, 128.97, 128.60, 126.16, 116.02, 112.93, 112.69, 74.84, 59.90, 58.52, 43.81, 43.26, 41.50, 33.09, 26.88, 26.16, 22.23. ESI-MS m/z 340.3 HRMS m/z calculated for C22H30NO2 [M+H]+, 340.2271; observed, 340.2282.

3-{1-Hydroxy-2-{[methyl(3-phenylpropyl)amino]methyl}cyclohexyl}phenol-HCl (5c)

White powder 120 mg 66% 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 9.59 (d, 1H), 9.38 (d, 1H), 7.36–7.26 (m, 2H), 7.15 (ddt, J=15.8, 10.2, 7.6 Hz, 4H), 6.99–6.79 (m, 2H), 6.63 (d, J=7.9 Hz, 1H), 5.01 (s, 1H), 2.85 (dd, J=13.8, 8.8 Hz, 2H), 2.77–2.60 (m, 1H), 2.57 (d, J=4.6 Hz, 2H), 2.48 (d, J=6.9 Hz, 2H), 2.41 (d, J=4.7 Hz, 2H), 2.17–1.29 (m, 11H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 157.67, 150.12, 140.97, 129.43, 128.84, 128.69, 126.56, 116.02, 113.74, 112.84, 74.19, 57.61, 57.11, 52.55, 42.32, 32.39, 27.02, 25.65, 25.07, 23.83, 21.58. ESI-MS m/z 354.3 [M+H]+ HRMS m/z calculated for C23H32NO2 [M+H]+, 354.2427; observed, 354.2435.

3-{1-hydroxy-2-{[methyl(4-phenylbutyl)amino]methyl}cyclohexyl}phenol-HCl (5d)

White powder 80 mg 68% 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 9.15 (s, 1H), 7.32–7.23 (m, 2H), 7.16 (d, J=10.0, 4.0 Hz, 3H), 7.06 (t, J=7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.90 (s, 1H), 6.82 (d, J=7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.55 (dd, J=7.9, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 4.83 (s, 1H), 2.54 (d, J=7.7 Hz, 2H), 2.26– 2.04 (m, 2H), 2.02–1.84 (m, 4H), 1.83–1.18 (m, 14H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 156.79, 151.29, 142.27, 128.44, 128.19, 125.56, 115.50, 112.41, 112.19, 74.38, 58.44, 57.44, 43.26, 42.65, 41.03, 34.96, 28.67, 26.46, 26.15, 25.70, 21.75. ESI-MS m/z368.3 [M+H]+ HRMS m/z calculated for C24H34NO2 [M+H]+, 368.2584; observed, 368.2588.

Radioligand binding assay

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells stably transfected with the human κ-opioid receptor and the δ-opioid receptor were obtained from SRI International (Palo Alto, CA, USA), and those transfected with the μ-opioid receptor were obtained from George Uh1 (NIDA Intramural Program, Bethesda, MD, USA). The cells were grown in 100-mm dishes in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's media (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin-streptomycin (10 000 U/mL) at 37 °C under 5% CO2 atmosphere. The affinity and selectivity of the compounds for multiple opioid receptors were determined by incubating the membranes with radiolabeled ligands and 12 different concentrations of the compounds at 25 °C in a final volume of 1 mL of 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.5. Incubation times of 60 min were used for the μ-selective peptide [3H]DAMGO, the κ-selective ligand [3H]U69593 and the δ-selective antagonist [3H]DPDPE.

[35S]GTP-γ-S functional assay

In a final volume of 0.5 mL, various concentrations of each tested compound were incubated with 7.5 mg of CHO cell membranes that stably expressed the human μ opioid receptor. The assay buffer consisted of 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 3 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.2 mmol/L EGTA, 3 mmol/L GDP, and 100 mmol/L NaCl. The final concentration of [35S]GTP-γ-S was 0.08 nmol/L. Nonspecific binding was measured by the inclusion of 10 mmol/L GTP-γ-S. Binding was initiated by the addition of the membranes. After an incubation of 60 min at 30 °C, reactions were terminated by rapid filtration and radio activity was determined by liquid scintillation counting.

Molecular simulation

The 3D structure of tramadol, M1, morphine, and codeine were built using the SYBYL6.9 program and optimized by a Gaussian program with the same method used in a previous study14. The 3D structures of the compounds were also superimposed using the software packages in SYBYL6.9.

Molecular docking was conducted using GOLD 5.0.115. The binding site was defined to include all residues within a 15.0 Å radius of the conserved D3.32Cγ carbon atom. A hydrogen-bond constraint was set between the protonated nitrogen atom (N1) of ligand and D3.32 side chain. Ten conformations were produced for each ligand and Gold-Score was used as the scoring function. Other parameters were set as standard default. High-scoring complexes were inspected visually to select the most reasonable solution.

Results

Design rationality

In previous studies over the past several years, tramadol is usually considered to be structurally related with codeine16,17,18. In our initial study, the three dimensional structures of tramadol and codeine were superimposed (Figure 2). It was found that the nitrogen atoms and 3-methoxylphenyl groups in both compounds were located in the same position, which showed that tramadol and codeine contained common pharmacophore features. As tramadol displays μ opioid activity primarily through its O-desmethyl metabolite (M1), morphine is also a more potent O-desmethyl metabolite of codeine. The 3D structure of M1 and morphine were also superimposed (Figure 2), which indicated that the two compounds contain the same pharmacophore features. Then, M1 and morphine were docked to a crystal structure of the μ opioid receptor (PDB code 4DKL) using the program GOLD 5.0.1. It was found that protonated nitrogen atoms in both compounds formed a salt bridge with Asp1473.32, while the phenol groups of the two compounds formed hydrogen binding interactions with water molecules (Figure 3A, 3B). These binding modes were consisted with morphinans' binding modes in the crystal structure of opioid receptors19,20,21. M1 maintained the classic interactions of morphinans with the μ opioid receptor. The superimposition and the docking studies showed that M1 and morphine have the same pharmacophore features and similar binding mode at the μ opioid receptor.

Superimposed 3D structure of tramadol and codeine; M1 and morphine.

Ligand binding modes at the μ opioid receptor. (A) The binding mode of M1 at μ opioid receptor is shown in green; (B) The binding mode of morphine at μ opioid receptor is shown in yellow; (C) The binding mode of N-phenethylnormorphine at μ opioid receptor is shown in blue; (D) The superimposition of the binding modes of M1 (green), morphine (yellow) and N-phenethylnormorphine (blue); (E) The superimposition of the binding modes of M1 (green), morphine (yellow) and N-phenethylnormorphine (blue), in which the μ opioid receptor is presented by its potential surface.

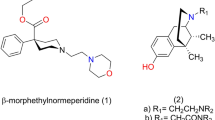

In carefully examining the binding modes of M1 and morphine, it was worth noting that the substituent on the nitrogen atom of both compounds faced a common hydrophobic pocket formed by Trp2936.48 and Tyr3267.43. It is well known that the introduction of N-arylalkyl substitutents, such as an N-phenylethyl group, is associated with significant improvement of opioid-like activities for classic morphinans. Introduction of an N-phenylethyl substituent on morphine significantly enhances the activity of morphine at the μ opioid receptor. The binding mode of N-phenethylnormorphine was also examined by molecular docking (Figure 3C). The N-phenethylnormorphine maintained the common binding interactions of M1 and morphine, while the N-phenylethyl portion extended into the hydrophobic pocket formed by Trp2936.48 and Tyr3267.43. This additional interaction may contribute to the improvement of N-phenethylnormorphine opioid activity compared with morphine. When the binding modes of M1, morphine and N-phenethylnormorphine were superimposed, we found that protonated nitrogen atoms in the three compounds formed salt bridges with Asp1473.32, while their phenol groups formed hydrogen binding interactions with water molecules and His2976.52 (Figure 3D). The N-substitution of the three compounds also faced the same hydrophobic pocket (Figure 3D, 3E). Because N-phenylethyl substitution can improve the opioid activity of morphine, we proposed that the introduction of a phenylalkyl group, such as phenylethyl, to the nitrogen atom of M1 may enhance the binding affinity at the μ opioid site as it does to morphine. Thus, we designed a series of N-phenylalkyl derivatives of tramadol (Figure 4) and M1 to investigate if this modification could improve the activity of the μ opioid receptor with the aim of developing a novel class of opioid ligands.

Designed N-arylalkylaminomethylenecyclohexanes analogues.

Synthesis

The synthesis of 4a–5d was described in Scheme 1. Cyclohexanone was condensed with paraformaldehyde and N-methylalkylphenylamine to afford aminomethylhexanones 3a–3d, which were further reacted with the Grignard reagent prepared from 3-bromoanisole to yield 4a–4d. Specifically, addition of the Grignard reagent to ketones 3a–3d provided crude 4a–4d as mixtures of diastereomers (76% cis for 4a–4d)16. The abundance of the cis-isomer could be improved to 95% by flash chromatography (DCM/MeOH, 20:1). O-desmethyl derivatives were prepared by removal of the O-methyl group of 5a–5d.

Reagents and conditions: (a) paraformaldehyde, HCl, isopropanol, 90 °C; (b) 3-bromoanisole, Mg, anhydrous THF, room temperature (RT); (c) BBr3, anhydrous DCM, −40 °C.

Binding affinity and functional activity

Similar to tramadol, all methoxyl derivatives, 4a–4d, did not display binding affinities for opioid receptors, while the phenolic hydroxyl derivatives, 5a–5d, exhibited higher affinities and selectivity against the μ opioid receptor. The binding affinities of 5a–5d ranged from 99.7 nmol/L to 1297 nmol/L (Table 1). We found that the μ opioid binding affinities of 5a–5d were associated with the length of the linker (number of carbon atoms between the nitrogen atom and the introduced phenyl group). When the length of the linker equaled 2, the corresponding target compound 5b displayed the highest binding affinity at the μ opioid receptor (Ki=99 nmol/L) among all the aminomethylenecyclohexane analogues. The binding affinity of 5b was slightly weaker than that of M1 (Ki=13 nmol/L), but maintained agonistic activity (EC50=258 nmol/L) (Figure 5) equal to M1 (EC50=244.7 nmol/L), as demonstrated in the [35S] GTP-γ-S binding assays (Table 2). When the length of the linker increased to 3 and 4, the agonistic activities were decreased 1-fold as compared with that of 5b.

The plot of GTPγS binding assay of 5b at the μ opioid receptor.

Discussion

In this study, the target compounds displayed similar structure and activity relationships with tramadol and that phenolic hydroxyl-substituted compounds were much more potent that methoxyl substituted compounds. For N-substitution, the length of the linker between the nitrogen atom and the introduced phenyl group had a substantial impact on opioid activity. The phenylethyl-substituted derivative 5b was the most potent compound and displayed agonist activity equal to M1.

Morphine and tramadol have the same pharmocophore model and binding mode (Figure 6A); however, the question remains as to whether their derivatives maintain similar properties? To answer this question, the binding modes of N-phenylethyl-substituted compound 5b and N-phenylethylmorphine were compared (Figure 6B and 6C). In terms of the binding modes of morphine and its analogues, N-phenylethylmorphine maintained the binding mode of morphine (Figure 6B). However, N-phenylethyl tramadol 5b changed the binding orientation of tramadol (Figure 6C). The cationic amines of 5b still formed a salt bridge with the carboxyl group of Asp1473.32, but the relative position of cationic amines were shifted to the downside of the carboxyl group in Asp1473.32. The N-phenylethyl group in 5b did not extend into the hydrophobic binding pocket formed by Trp2936.48and Tyr3267.43, as was observed for the phenyl group of N-phenethylnormorphine. Instead, it was extended into a new pocket formed by the residues Ile1443.29, Val1433.28, and Leu219 in the second extracellular loop (ECL2). This new interaction resulted in the downside movement of the ligand and the phenol group in 5b failed to form the hydrogen binding network composed of two water molecules and His2976.52 (Figure 6C and 6D). The results showed that the introduction of an N-phenylethyl group changed the original binding orientation of tramadol and morphine; the activity of N-phenylethyl tramadol 5b decreased 8-fold, but maintained similar agonistic activity (EC50=258 nmol/L and 244 nmol/L for 5b and M1, respectively). Due to the downside movement of 5b in the active site, the key water-mediated interaction between the phenol group in M1 and His2976.52 of the μ opioid receptor disappeared and a space was created. The introduction of a new hydrogen bond donor in the phenol group of 5b may restore the hydrogen binding network composed of two water molecules and His2976.52 and increase its activity with the μ receptor.

Ligand binding modes at the μ opioid receptor. (A) Superimposed binding modes of M1 (green) and morphine (yellow) at the μ opioid receptor; (B) Superimposed binding modes of morphine (yellow) and N-phenethylnormorphine (blue) at the μ opioid receptor; (C) Superimposed binding modes of M1 (green) and 5b (pink) at μ the opioid receptor. (D) The binding mode of 5b is shown in pink.

In this study, we found that tramadol active metabolite M1 and morphine had common pharmacophore features and similar binding modes at the μ opioid receptor using 3D structure superimposition and a molecular docking technique. The attachment of N-phenylethyl to morphine introduced hydrophobic interactions with Trp2936.48 and Tyr3267.43 and improved its opioid activity. Then, a series of N-phenylalkyl substituted derivatives of tramadol were designed, synthesized and evaluated for opioid activity. The N-phenylethyl substituted compound 5b displayed equivalent activity in functional assays in comparison to M1. Further, a molecular docking study with 5b identified that 5b adopted a novel binding orientation, unlike N-phenylethyl morphine, where the N-phenylethyl group of 5b extended into another hydrophobic pocket formed by the residues Ile1443.29, Val1433.28, and Leu219 in ECL2. Our study indicated that the introduction of a new hydrogen bond donor in the phenol group of 5b may restore the original water bridge hydrogen binding network and increase its activity with the μ receptor.

Author contribution

Wei FU, Wei LI, and Qing SHEN designed the research; Qing SHEN and Yuan-yuan QIAN synthesized the compounds; Xue-jun XU and Jing-gen LIU performed the pharmacological assay; and Qing SHEN and Wei FU wrote the paper.

References

Grond S, Sablotzki A . Clinical pharmacology of tramadol. Clin Pharmacokinet 2004; 43: 879–923.

Harati Y, Gooch C, Swenson M, Edelman S, Greene D, Raskin P, et al. Double-blind randomized trial of tramadol for the treatment of the pain of diabetic neuropathy. Neurology 1998; 50: 1842–6.

Harati Y, Gooch C, Swenson M, Edelman SV, Greene D, Raskin P, et al. Maintenance of the long-term effectiveness of tramadol in treatment of the pain of diabetic neuropathy. J Diabetes Complications 2000; 14: 65–70.

Barber J . Examining the use of tramadol hydrochloride as an antidepressant. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2011; 19: 123–30.

Gobel H, Stadler T . Treatment of post-herpes zoster pain with tramadol. Results of an open pilot study versus clomipramine with or without levomepromazine. Drugs 1997; 53: 34–9.

Boureau F, Legallicier P, Kabir-Ahmadi M . Tramadol in post-herpetic neuralgia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pain 2003; 104: 323–31.

Wu T, Yue X, Duan X, Luo DY, Cheng Y, Tian Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of tramadol for premature ejaculation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Urology 2012; 80: 618–24.

Wong BLK, Malde S . The use of tramadol “on-demand” for premature ejaculation: a systematic review. Urology 2013; 81: 98–103.

Langley PC, Patkar AD, Boswell KA, Benson CJ, Schein JR . Adverse event profile of tramadol in recent clinical studies of chronic osteoarthritis pain. Curr Med Res Opin 2010; 26: 239–51.

Keating GM . Tramadol sustained-release capsules. Drugs 2006; 66: 223–30.

Gobbi M, Moia M, Pirona L, Ceglia I, Reyes-Parada M, Scorza C, et al. p-Methylthioamphetamine and 1-(m-chlorophenyl)piperazine, two non-neurotoxic 5-HT releasers in vivo, differ from neurotoxic amphetamine derivatives in their mode of action at 5-HT nerve endings in vitro. J Neurochem 2002; 82: 1435–43.

Reimann W, Schneider F . Induction of 5-hydroxytryptamine release by tramadol, fenfluramine and reserpine. Eur J Pharmacol 1998; 349: 199–203.

Gillen C, Haurand M, Kobelt DJ, Wnendt S . Affinity, potency and efficacy of tramadol and its metabolites at the cloned human mu-opioid receptor. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2000; 362: 116–21.

Yu Z, Ma YC, Ai J, Chen DQ, Zhao DM, Wang X, et al. Energetic factors determining the binding of type I inhibitors to c-Met kinase: experimental studies and quantum mechanical calculations. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2013; 34: 1475–83.

Jones G, Willett P, Glen RC, Leach AR, Taylor R . Development and validation of a genetic algorithm for flexible docking. J Mol Biol 1997; 267: 727–48.

Shao L, Abolin C, Hewitt MC, Koch P, Varney M . Derivatives of tramadol for increased duration of effect. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2006; 16: 691–4.

Shao L, Wang F, Hewitt MC, Barberich TJ . mu-Opioid/5-HT4 dual pharmacologically active agents-efforts towards an effective opioid analgesic with less GI and respiratory side effects (Part I). Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2009; 19: 5679–83.

Buschmann H, Christoph T, Maul C, Sundermann B, editors. Analgesics: from chemistry and pharmacology to clinical application. Germany: Heppenheim; 2002.

Granier S, Manglik A, Kruse AC, Kobilka TS, Thian FS, Weis WI, et al. Structure of the delta-opioid receptor bound to naltrindole. Nature 2012; 485: 400–4.

Manglik A, Kruse AC, Kobilka TS, Thian FS, Mathiesen JM, Sunahara RK, et al. Crystal structure of the micro-opioid receptor bound to a morphinan antagonist. Nature 2012; 485: 321–6.

Wu H, Wacker D, Mileni M, Katritch V, Han GW, Vardy E, et al. Structure of the human kappa-opioid receptor in complex with JDTic. Nature 2012; 485: 327–32.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (No 14431990500) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No 81473136 and 30901857).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shen, Q., Qian, Yy., Xu, Xj. et al. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of N-phenylalkyl-substituted tramadol derivatives as novel μ opioid receptor ligands. Acta Pharmacol Sin 36, 887–894 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/aps.2014.171

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/aps.2014.171

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Modulation of social and depression behaviors in cholestatic and drug-dependent mice: possible role of opioid receptors

Journal of Diabetes & Metabolic Disorders (2022)

-

Chemistry and synthesis of major opium alkaloids: a comprehensive review

Journal of the Iranian Chemical Society (2021)