Abstract

Enhanced properties in modern functional materials can often be found at structural transition regions, such as morphotropic phase boundaries (MPB), owing to the coexistence of multiple phases with nearly equivalent energies. Strain-engineered MPBs have emerged in epitaxially grown BiFeO3 (BFO) thin films by precisely tailoring a compressive misfit strain, leading to numerous intriguing phenomena, such as a massive piezoelectric response, magnetoelectric coupling, interfacial magnetism and electronic conduction. Recently, an orthorhombic–rhombohedral (O–R) phase boundary has also been found in tensile-strained BFO. In this study, we characterise the crystal structure and electronic properties of the two competing O and R phases using X-ray diffraction, scanning probe microscope and scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM). We observe the temperature evolution of R and O domains and find that the domain boundaries are highly conductive. Temperature-dependent measurements reveal that the conductivity is thermally activated for R–O boundaries. STEM observations point to structurally wide boundaries, significantly wider than in other systems. Therefore, we reveal a strong correlation between the highly conductive domain boundaries and structural material properties. These findings provide a pathway to use phase boundaries in this system for novel nanoelectronic applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multiferroic BiFeO3 (BFO) has attracted great interest as a promising lead-free functional material owing to its key properties, including electromechanical and magnetoelectric coupling, domain wall conductance, bias-induced semiconductor–insulator transitions and photovoltaic effects.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Bismuth ferrite is a room temperature multiferroic perovskite exhibiting antiferromagnetism that is coupled with ferroelectric order.8 Below the Curie temperature, bulk BFO is considered to have a rhombohedral R3c space group structure that allows antiphase octahedral tilting and ionic displacements from the center of symmetry along the [111] pseudocubic direction.9, 10 The recent discovery of a strain-induced morphotropic phase boundary in BFO films grown on (001) LaAlO3 has attracted further interest with the compressive strain imposed by an underlying substrate stabilizing a tetragonally distorted phase.11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Mixed-phase regions exhibit the coexistence of both R- and T-like phases with the ability to selectively switch between the two phases by an external electric field and force.18, 19, 20, 21, 22 Interestingly, the strong correlation between T–R interfaces and their enhanced properties, such as the finding of a large electric-field-induced strain23 and a giant piezoelectric d33 coefficient, led to extensive studies of bismuth ferrite films under compressive strain by both experimental and theoretical approaches. Moreover, a correlation between the elasticity at the T–R interfaces and electronic conduction was also reported.24 Triggered by these studies, several theoretical predictions have also been made to report on the influence of epitaxial strain on the multiferroic BFO with strain–temperature phase diagrams composing phases with different symmetries.11, 25

An orthorhombic phase in bismuth ferrite films has been predicted by first principle calculations26, 27 based on tensile misfit strain and thermodynamic theories.28 Recent studies show a pathway to stabilize this new orthorhombic phase in BFO films via strain engineering.29, 30 Moreover, an orthorhombic-like–rhombohedral-like (O–R) phase boundary has also been investigated in rare-earth-substituted bismuth ferrite films that exhibit an enhanced piezoelectric and dielectric response.31, 32 Lee et al.33 recently investigated tensile-strained BFO thin films, revealing their magnetic properties of R and O phases and associated electrical switchability. These pioneering developments thus open a new prospect for an O–R mixed-phase boundary in bismuth ferrite thin films under tensile misfit strain; however, thorough investigations are required to explore this material and further unveil its functional properties.

Here we explore the key features of tensile-strained R–O BFO to gain a better understanding of crystal structures and electronic properties by using various advanced techniques, such as temperature-dependent X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning probe microscope (atomic force microscopy (AFM), piezoresponse force microscopy (PFM), conductive AFM (c-AFM)) and scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM). Our investigations on ferroelectric domain structures and electronic conduction show that the domain boundaries of R-BFO and O-BFO are highly conductive and that their conductivity is thermally activated. We also reveal that the rotation of the ferroelectric polarization vector between R and O occurs over an unusually wide range of approximately 15 unit cells. These findings point to potential interesting applications of this tensile-strained R–O BFO for nanoelectronic applications.

Materials and methods

In this study, we used epitaxial BFO thin films grown on (110)pc-oriented GdScO3 (GSO) substrates with a thin SrRuO3 buffer layer via pulsed laser deposition. The GSO substrate has an orthorhombic structure with lattice constants of a=5.7454 Å, b=7.9314 Å and c=5.4805 Å. The [110]pc pseudocubic direction of the substrate corresponds to the [001]o orthorhombic direction. During the deposition, the substrate temperature and oxygen pressure were fixed at 700 °C and 100 mTorr. A KrF excimer laser (Coherent Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA, λ=248 nm) was operated with a repetition rate of 10 Hz, and the laser fluence was adjusted to ~1 J cm−2. For insight into the temperature-dependent crystal structures, θ−2θ scans and reciprocal space maps (RSMs) during an additional heating and cooling run process were carried out by an X-ray diffractometer (PANalytical X’pert MRD PRO equipped with an Anton Paar DHS 1100, PANalytical B.V., Almelo, The Netherlands) with Cu Kα1 radiation. An AIST-NT scanning probe microscope (AIST-NT Inc., Novato, CA, USA) was used for PFM and c-AFM measurements with an additional heating stage for temperature-dependent measurements. We used diamond tips (DCP20, MikroMasch, Watsonville, CA, USA) with a spring constant of ~48 N m−1; a PFM AC voltage of 0.2 V was applied at a frequency of 2089 kHz and −2 to −3 V was used for c-AFM imaging with scan rates of 2 and 3 μm s−1, respectively. An FEI Titan 60–300 microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA) equipped with aberration correctors for both probe forming and imaging was used for the STEM characterization of the thin film in a cross-sectional view. The microscope was operated at 300 kV, with convergence angles of the incident electron beam and the collection angle of 21.4 and 79–200 mrad, respectively.

Results and Discussion

In tensile-strained BFO, the R phase has a polarization orientation along the <111>pc directions with a monoclinic distortion; as a result, the [110]pc axis is slightly tilted toward [001]pc, whereas the ferroelectric polarization of the O phase lies within the (110)pc plane and hence possesses no out-of-plane ferroelectric polarization. With this in mind, three-way switching was recently demonstrated by an electric field to control out-of-plane polarization.33 To explore the temperature-dependent structures of R–O BFO, we carried out a series of temperature-dependent X-ray θ−2θ scans around the (110)pc GSO Bragg reflection for the films ranging from 300 to 680 K (Supplementary Information SI, Supplementary Figure S1a). We first note that the films show only the (110)pc R-BFO and O-BFO reflections without any other reflections from impurity phases, confirming the epitaxial growth of the films on the GSO substrate. This is consistent with the observation of no obvious protruding surface features in the AFM image (Figure 2a), showing smooth surface morphology with a root mean square roughness of 0.89 nm. Based on the series of temperature-dependent XRD scans, we also show the trend of peak areas and out-of-plane lattice constants of both R-BFO and O-BFO along with increasing temperature (Supplementary Figures S1b and c, respectively). We observe structural changes of R and O phases such that, as temperature increases, both out-of-plane lattice constants increase as a result of thermal expansion, whereas the peak area of O phase in fact decreases along with a slight increase in R-phase peak area. To directly see the thermal effect on the structure, we performed an X-ray θ−2θ scan (Figure 1a) and RSMs around BFO (110)pc with the horizontal axis of the scattering plane aligned to [001]pc and [1–10]pc at 300 and 600 K (Figures 1b and c, respectively). A comparison of the peaks and rocking curves of the O-phase (inset image of Figure 1a) reveals that the peak intensity at 600 K clearly decreases without shifting of the peak from the normal 2θ line for both in-plane directions of [001]pc and [1–10]pc. Because all scales of the displayed RSMs are the same, we can directly compare the peak shapes of R-BFO and O-BFO for the selected temperatures. We find that the peak intensities of O-BFO decrease at 600 K for both in-plane directions of [001]pc and [1–10]pc. Through repeated heating and cooling runs of XRD studies, the peak intensity of O-BFO does not recover and decreases after several runs, likely owing to residual strain relaxation induced by heating.

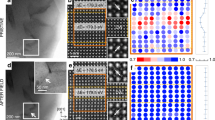

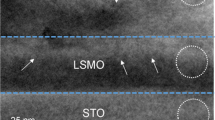

To further investigate the ferroelectric domain structures and functionality of the R–O mixed BFO, we performed scanning probe microscopic studies via AFM, PFM and c-AFM. The topography scan image (Figure 2a) of a 2 × 2 μm2 reference area shows a smooth surface with a root mean square roughness of 0.89 nm, and the lateral amplitude and phase PFM images are shown in Figures 2b and c, respectively. The ferroelectric domains of the O–R mixed phases are differentiated by contrast of bright and dark regions. Small, bright, needle-shaped areas represent O domains, whereas dark regions are R domains owing to the different magnitudes of in-plane ferroelectric polarization. For electronic conduction, a c-AFM scan image (Figure 2d) was taken with a bias of −2 V on the same reference area. Domain boundaries clearly show a largely enhanced local conductivity at least two orders of magnitude greater than that inside the domains themselves.

Temperature-dependent c-AFM measurements were performed to evaluate the thermal activation of conductivity in tensile-strained BFO. We took a series of c-AFM scans of 10 × 10 μm2 areas at temperatures ranging from 300 to 406 K (Supplementary Information SII). As can be seen, the conductivity is thermally activated for domains and phase boundaries of tensile-strained BFO. By plotting histograms of the current profile with Gaussian fitting (Supplementary Information SIII), we find two peaks of current for the domains and phase boundaries at each temperature (Figure 3a and Supplementary Figure S3). Using this method, the current values in logarithmic scale are plotted against the inverse of the temperature (1/T) (Figure 3b). Moreover, this relation was used together with the non-ideal diode equation to calculate the activation energy (Supplementary Information SIV). Absolute values for the activation energies lie in the range of 0.2–0.4 eV. The difference in activation energy between the two is rather small in the ~0.2 eV range. In fact, similar activation energies have been found for 109° ferroelectric domain walls in La-doped BFO34 and phase boundaries of Ca-doped BFO.35

(a) Histogram plot of the c-AFM scan data wherein x axis represents current and y axis represents the frequency of data points on a log scale. Multiple peak fit is performed to find two Gaussian peaks corresponding to average background and phase boundary current values. Inset shows the c-AFM scan at room temperature on a 10 × 10 μm2 area of the BFO/GSO (110)pc with application of −3 V. (b) Relationship between current in logarithmic scale and inverse of temperature (1/T). Slopes of current in natural logarithmic scale versus inverse of temperature are used to calculate activation energy of R and O domain and phase boundary based on Arrhenius behavior.

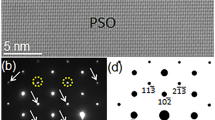

To acquire deeper insight into the conductivity observed in c-AFM, we performed STEM studies of the structural phases and the boundaries between them (Figure 4). The structural R and O phases can be identified from the high-angle annular dark field (HAADF) image (Figure 4a). The local ferroelectric polarization vector of R- and O-phases (Figures 4b and c, respectively) can be assigned by the relative iron displacement vectors, which are determined by a fit of the image intensities to two-dimensional Gaussians, and they have a linear relationship with the projected polarization.36 The change in longitudinal polarization from R-BFO to O-BFO is also clearly shown (Figure 4d). We note a slight inclination of the phase boundary position (Supplementary Information SV, Supplementary Figure S4). Interestingly, the ferroelectric transition occurs within a length of ~15 unit cells, which is surprisingly wide compared with other systems—for example, R to T structural phase transitions34, 35 and ferroelectric domain transitions across charged domain walls37 in BFO. Previous studies of the undoped material on LaAlO3 substrate revealed that the transition from structural variant R to T was occurring within a length of 10 unit cells.23 The presence of the O phase therefore seems to lead to much wider phase boundaries. It has been estimated that such polarization rotation leads to enhanced electromechanical properties via theoretical modeling and calculations.28, 32 In addition to the relation between piezoresponse and ferroelectric rotation, we suggest that ferroelectric motion between R and O domains through a wide length (>15 unit cells) is a significant factor for domain wall conduction with more than two orders of magnitude compared with the insides of the domains.

(a) STEM HAADF image of O–R phase boundary. (b, c) Polarization vector mapping results of R- and O-phase, respectively, showing their polarization directions. (d) Quantitative analysis of atomic displacements along the blue line in HAADF image during ferroelectric polarization rotation between R-BFO and O-BFO.

Local strain changes, determined from geometric phase analysis of BFO/GSO (110)pc using R phase as a reference, are also shown (Figure 5 and Supplementary Figure S5). With respect to the structure and dimension of the STEM image (Figure 5a), the strain mapping image along the outside of the plane direction shows a drastic change in strain across the phase boundary between R and O phases (Figure 5b). This can also be clearly seen in the cross-sectional profile of strain (Figure 5d) along the yellow arrow in the image. Moreover, the unit cell rotation angle (Figure 5c) with respect to R-BFO has been mapped across the image, indicating that the O-phase has a shear strain owing to its different space group. For this, strain tensor calculations are used (Supplementary Information SVI). Cross-section analysis (Figure 5e) of the rotation angle confirms the strain rotation angle at the phase boundary with respect to the same yellow arrow in the image. Recent microscopic work38, 39 has shown interplay between strains at the interface and octahedral tilt in BFO. Therefore, our results show large strain gradients (atomic distance changes) at the boundaries, which result in altered octahedral tilts and bonding angles at the phase boundaries. In the present case, changes in the oxygen octahedral tilt and changes in the Fe–O–Fe bond angle lead to changed orbital mixing angles. The Fe–O–Fe angle is important because it controls both the magnetic exchange and orbital overlap between Fe 3d and O 2p orbitals, and as such it determines the magnetic ordering temperature and the conductivity of the material. In fact, the close relation between phase boundary conductivity and oxygen octahedral tilt has been discussed.40 The observed difference in conductivity at the phase boundaries (Figure 2d) can then be attributed to local changes in the Fe–O–Fe angle.

(a) STEM HAADF image of BFO/GSO (110)pc. Geometric phase analysis for (b) strain mapping image of the structure with lattice strain along out of plane direction and (c) strain rotation angle image within the structure. All these strain images are with respect to dimension of the STEM image and R-BFO as a reference for strain analysis. Cross-section profile of (d) strain and (e) strain rotation angle versus distance for the yellow arrow in b, c, respectively.

In summary, we have shown that there is a strong correlation between the local strain state and electronic properties at the O–R phase boundaries in mixed-phase BFO thin films. We clearly identify a thermally activated conduction mechanism. This rather unusual electrical feature might find applications in nanotechnology. Furthermore, the recent discovery of enhanced ferromagnetism in highly strained BFO thin films with the magnetic moment lying along the phase boundaries suggests the high potential of this system for magnetoresistive and nanoelectronic technologies.5, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46

References

Ko, K. T., Jung, M. H., He, Q., Lee, J. H., Woo, C. S., Chu, K., Seidel, J., Jeon, B. G., Oh, Y. S., Kim, K. H., Liang, W. I., Chen, H. J., Chu, Y. H., Jeong, Y. H., Ramesh, R., Park, J. H. & Yang, C. H. Concurrent transition of ferroelectric and magnetic ordering near room temperature. Nat. Commun. 2, 567 (2011).

Rovillain, P., de Sousa, R., Gallais, Y., Sacuto, A., Measson, M. A., Colson, D., Forget, A., Bibes, M., Barthelemy, A. & Cazayous, M. Electric-field control of spin waves at room temperature in multiferroic BiFeO3 . Nat. Mater. 9, 975–979 (2010).

Yang, C. H., Seidel, J., Kim, S. Y., Rossen, P. B., Yu, P., Gajek, M., Chu, Y. H., Martin, L. W., Holcomb, M. B., He, Q., Maksymovych, P., Balke, N., Kalinin, S. V., Baddorf, A. P., Basu, S. R., Scullin, M. L. & Ramesh, R. Electric modulation of conduction in multiferroic Ca-doped BiFeO3 films. Nat. Mater. 8, 485–493 (2009).

Choi, T., Lee, S., Choi, Y. J., Kiryukhin, V. & Cheong, S.-W. Switchable ferroelectric diode and photovoltaic effect in BiFeO3 . Science 324, 63–66 (2009).

Zhao, T., Scholl, A., Zavaliche, F., Lee, K., Barry, M., Doran, A., Cruz, M. P., Chu, Y. H., Ederer, C., Spaldin, N. A., Das, R. R., Kim, D. M., Baek, S. H., Eom, C. B. & Ramesh, R. Electrical control of antiferromagnetic domains in multiferroic BiFeO3 films at room temperature. Nat. Mater. 5, 823–829 (2006).

Seidel, J. Domain walls as nanoscale functional elements. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 3, 2905–2909 (2012).

Seidel, J., Fu, D., Yang, S.-Y., Alarcón-Lladó, E., Wu, J., Ramesh, R. & Ager, J. W. III. Efficient photovoltaic current generation at ferroelectric domain walls. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 126805 (2011).

Catalan, G. & Scott, J. F. Physics and applications of bismuth ferrite. Adv. Mater. 21, 2463–2485 (2009).

Moreau, J. M., Michel, C., Gerson, R. & James, W. J. Ferroelectric BiFeO3 X-ray and neutron diffraction study. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 32, 1315–1320 (1971).

Kubel, F. & Schmid, H. Structure of a ferroelectric and ferroelastic monodomain crystal of the perovskite BiFeO3 . Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B 46, 698–702 (1990).

Zeches, R. J., Rossell, M. D., Zhang, J. X., Hatt, A. J., He, Q., Yang, C.-H., Kumar, A., Wang, C. H., Melville, A., Adamo, C., Sheng, G., Chu, Y.-H., Ihlefeld, J. F., Erni, R., Ederer, C., Gopalan, V., Chen, L. Q., Schlom, D. G., Spaldin, N. A., Martin, L. W. & Ramesh, R. A strain-driven morphotropic phase boundary in BiFeO3 . Science 326, 977–980 (2009).

Béa, H., Dupé, B., Fusil, S., Mattana, R., Jacquet, E., Warot-Fonrose, B., Wilhelm, F., Rogalev, A., Petit, S., Cros, V., Anane, A., Petroff, F., Bouzehouane, K., Geneste, G., Dkhil, B., Lisenkov, S., Ponomareva, I., Bellaiche, L., Bibes, M. & Barthélémy, A. Evidence for room-temperature multiferroicity in a compound with a giant axial ratio. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 217603 (2009).

MacDougall, G. J., Christen, H. M., Siemons, W., Biegalski, M. D., Zarestky, J. L., Liang, S., Dagotto, E. & Nagler, S. E. Antiferromagnetic transitions in tetragonal-like BiFeO3 . Phys. Rev. B 85, 100406 (2012).

Chen, Z., Luo, Z., Huang, C., Qi, Y., Yang, P., You, L., Hu, C., Wu, T., Wang, J., Gao, C., Sritharan, T. & Chen, L. Low-symmetry monoclinic phases and polarization rotation path mediated by epitaxial strain in multiferroic BiFeO3 thin films. Adv. Funct. Mater. 21, 133–138 (2011).

Kreisel, J., Jadhav, P., Chaix-Pluchery, O., Varela, M., Dix, N., Sanchez, F. & Fontcuberta, J. A phase transition close to room temperature in BiFeO3 thin films. J. Phys. Condes. Matter 23, 342202 (2011).

Choi, K. Y., Do, S. H., Lemmens, P., Wulferding, D., Woo, C. S., Lee, J. H., Chu, K. & Yang, C. H. Anomalous low-energy phonons in nearly tetragonal BiFeO3 thin films. Phys. Rev B 84, 132408 (2011).

Siemons, W., Biegalski, M. D., Nam, J. H. & Christen, H. M. Temperature-driven structural phase transition in tetragonal-like BiFeO3 . Appl. Phys. Express 4, 095801 (2011).

Zhou, J., Trassin, M., He, Q., Tamura, N., Kunz, M., Cheng, C., Zhang, J., Liang, W.-I., Seidel, J., Hsin, C.-L. & Wu, J. Directed assembly of nano-scale phase variants in highly strained BiFeO3 thin films. J. Appl. Phys. 112, 064102 (2012).

Chen, Y. C., He, Q., Chu, F. N., Huang, Y. C., Chen, J. W., Liang, W. I., Vasudevan, R. K., Nagarajan, V., Arenholz, E., Kalinin, S. V. & Chu, Y. H. Electrical control of multiferroic orderings in mixed-phase BiFeO3 films. Adv. Mater. 24, 3070–3075 (2012).

You, L., Chen, Z. H., Zou, X., Ding, H., Chen, W. G., Chen, L., Yuan, G. L. & Wang, J. L. Characterization and manipulation of mixed phase nanodomains in highly strained BiFeO3 thin films. ACS Nano 6, 5388–5394 (2012).

Zhu, Q. X., Wang, W., Zhao, X. Q., Li, X. M., Wang, Y., Luo, H. S., Chan, H. L. W. & Zheng, R. K. Tunable strain effect and ferroelectric field effect on the electronic transport properties of La0.5Sr0.5CoO3 thin films. J. Appl. Phys. 111, 103702 (2012).

Heo, Y., Jang, B.-K., Kim, S. J., Yang, C.-H. & Seidel, J. Nanoscale mechanical softening of morphotropic BiFeO3 . Adv. Mater. 26, 7568–7572 (2014).

Zhang, J. X., XiangB, HeQ, SeidelJ, Zeches, R. J., YuP, Yang, S. Y., Wang, C. H., Chu, Y. H., Martin, L. W., Minor, A. M. & Ramesh, R. Large field-induced strains in a lead-free piezoelectric material. Nat. Nano 6, 98–102 (2011).

Sharma, P., Heo, Y., Jang, B.-K., Liu, Y. Y., Valanoor, N., Li, J., Yang, C.-H. & Seidel., J. Morphotropic phase elasticity of strained BiFeO3 . Adv. Mater. Interf. 3, 1600033 (2016).

Infante, I. C., Lisenkov, S., Dupé, B., Bibes, M., Fusil, S., Jacquet, E., Geneste, G., Petit, S., Courtial, A., Juraszek, J., Bellaiche, L., Barthélémy, A. & Dkhil, B. Bridging multiferroic phase transitions by epitaxial strain in BiFeO3 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 057601 (2010).

Yang, Y., Ren, W., Stengel, M., Yan, X. H. & Bellaiche, L. Revisiting properties of ferroelectric and multiferroic thin films under tensile strain from first principles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 057602 (2012).

Lee, J.-H., Oak, M.-A., Choi, H. J., Son, J. Y. & Jang, H. M. Rhombohedral-orthorhombic morphotropic phase boundary in BiFeO3-based multiferroics: first-principles prediction. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 1667–1672 (2012).

Liu, Y. Y., Yang, L. & Li, J. Y. Strain-engineered orthorhombic-rhombohedral phase boundary in epitaxial bismuth ferrite films. J. Appl. Phys. 113, 183524 (2013).

Zhang, J. X., Li, Y. L., Choudhury, S., Chen, L. Q., Chu, Y. H., Zavaliche, F., Cruz, M. P., Ramesh, R. & Jia, Q. X. Computer simulation of ferroelectric domain structures in epitaxial BiFeO3 thin films. J. Appl. Phys. 103, 094111 (2008).

Yang, J. C., He, Q., Suresha, S. J., Kuo, C. Y., Peng, C. Y., Haislmaier, R. C., Motyka, M. A., Sheng, G., Adamo, C., Lin, H. J., Hu, Z., Chang, L., Tjeng, L. H., Arenholz, E., Podraza, N. J., Bernhagen, M., Uecker, R., Schlom, D. G., Gopalan, V., Chen, L. Q., Chen, C. T., Ramesh, R. & Chu, Y. H. Orthorhombic BiFeO3 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 109 (2012).

Fujino, S., Murakami, M., Anbusathaiah, V., Lim, S. H., Nagarajan, V., Fennie, C. J., Wuttig, M., Salamanca-Riba, L. & Takeuchi, I. Combinatorial discovery of a lead-free morphotropic phase boundary in a thin-film piezoelectric perovskite. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 202904–202903 (2008).

Cheng, C.-J., Kan, D., Anbusathaiah, V., Takeuchi, I. & Nagarajan, V. Microstructure-electromechanical property correlations in rare-earth-substituted BiFeO3 epitaxial thin films at morphotropic phase boundaries. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 212905 (2010).

Lee, J. H., Chu, K., Ünal, A. A., Valencia, S., Kronast, F., Kowarik, S., Seidel, J. & Yang, C.-H. Phase separation and electrical switching between two isosymmetric multiferroic phases in tensile strained BiFeO3 thin films. Phys. Rev. B 89, 140101 (2014).

Seidel, J., Maksymovych, P., Batra, Y., Katan, A., Yang, S. Y., He, Q., Baddorf, A. P., Kalinin, S. V., Yang, C. H., Yang, J. C., Chu, Y. H., Salje, E. K. H., Wormeester, H., Salmeron, M. & Ramesh, R. Domain wall conductivity in La-doped BiFeO3 . Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 197603 (2010).

Seidel, J., Trassin, M., Zhang, Y., Maksymovych, P., Uhlig, T., Milde, P., Köhler, D., Baddorf, A. P., Kalinin, S. V., Eng, L. M., Pan, X. & Ramesh, R. Electronic properties of isosymmetric phase boundaries in highly strained Ca-doped BiFeO3 . Adv. Mater. 26, 4376–4380 (2014).

Nelson, C. T., Winchester, B., Zhang, Y., Kim, S.-J., Melville, A., Adamo, C., Folkman, C. M., Baek, S.-H., Eom, C.-B., Schlom, D. G., Chen, L.-Q. & Pan, X. Spontaneous vortex nanodomain arrays at ferroelectric heterointerfaces. Nano Lett. 11, 828–834 (2011).

Borisevich, A., Ovchinnikov, O. S., Chang, H. J., Oxley, M. P., Yu, P., Seidel, J., Eliseev, E. A., Morozovska, A. N., Ramesh, R., Pennycook, S. J. & Kalinin, S. V. Mapping octahedral tilts and polarization across a domain wall in BiFeO3 from Z-contrast scanning transmission electron microscopy image atomic column shape analysis. ACS Nano 4, 6071–6079 (2010).

Kim, Y.-M., Kumar, A., Hatt, A., Morozovska, A. N., Tselev, A., Biegalski, M. D., Ivanov, I., Eliseev, E. A., Pennycook, S. J., Rondinelli, J. M., Kalinin, S. V. & Borisevich, A. Y. Interplay of octahedral tilts and polar order in BiFeO3 films. Adv. Mater. 25, 2497–2504 (2013).

Kim, Y.-M., Morozovska, A., Eliseev, E., Oxley, M. P., Mishra, R., Selbach, S. M., Grande, T., Pantelides, S. T., Kalinin, S. V. & Borisevich, A. Y. Direct observation of ferroelectric field effect and vacancy-controlled screening at the BiFeO3/LaxSr1−xMnO3 interface. Nat. Mater. 13, 1019–1025 (2014).

Catalan, G. On the link beween octahedral rotations and conductivity in the domain walls of BiFeO3 . Ferroelectrics 433, 65–73 (2012).

Chu, Y.-H., Martin, L. W., Holcomb, M. B., Gajek, M., Han, S.-J., He, Q., Balke, N., Yang, C.-H., Lee, D., Hu, W., Zhan, Q., Yang, P.-L., Fraile-Rodriguez, A., Scholl, A., Wang, S. X. & Ramesh, R. Electric-field control of local ferromagnetism using a magnetoelectric multiferroic. Nat. Mater. 7, 478–482 (2008).

Heron, J. T., Trassin, M., Ashraf, K., Gajek, M., He, Q., Yang, S. Y., Nikonov, D. E., Chu, Y. H., Salahuddin, S. & Ramesh, R. Electric-field-induced magnetization reversal in a ferromagnet-multiferroic heterostructure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 217202 (2011).

Trassin, M., Clarkson, J. D., Bowden, S. R., Liu, J., Heron, J. T., Paull, R. J., Arenholz, E., Pierce, D. T. & Unguris, J. Interfacial coupling in multiferroic/ferromagnet heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 87, 134426 (2013).

Catalan, G., Seidel, J., Ramesh, R. & Scott, J. F. Domain wall nanoelectronics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 84, 119–156 (2012).

Skumryev, V., Laukhin, V., Fina, I., Martí, X., Sánchez, F., Gospodinov, M. & Fontcuberta, J. Magnetization reversal by electric-field decoupling of magnetic and ferroelectric domain walls in multiferroic-based heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 057206 (2011).

Parkin, S. S. P., Hayashi, M. & Thomas, L. Magnetic domain-wall racetrack memory. Science 320, 190–194 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We thnk support by the Australian Research Council under grant numbers FT110100523, DP140100463 and DP140102849 and by the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (Contract Nos. 2011-0016133 and NRF-2013S1A2A2035418). The TEM work was supported by the Department of Energy (DOE) under grant number DE-SC0014430, the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Project No. 51302132 and the National Basic Research Program of China under grant number 2015CB654900.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the NPG Asia Materials website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Heo, Y., Hong Lee, J., Xie, L. et al. Enhanced conductivity at orthorhombic–rhombohedral phase boundaries in BiFeO3 thin films. NPG Asia Mater 8, e297 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/am.2016.120

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/am.2016.120

This article is cited by

-

Twisted oxide lateral homostructures with conjunction tunability

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Tailoring the multiferroic properties of BiFeO3 by low energy ions implantation

Journal of Electroceramics (2021)

-

Electromechanical-mnemonic effects in BiFeO3 for electric field history-dependent crystallographic phase patterning

Journal of Materials Science (2018)