Abstract

Nanosizing is the fashionable method to obtain a desirable electrode material for energy storage applications, and thus, a question arises: do smaller electrode materials exhibit better electrochemical performance? In this context, theoretical analyses on the particle size, band gap and conductivity of nano-electrode materials were performed; it was determined that a critical size exist between particle size and electrochemical performance. To verify this determination, for the first time, a scalable formation and disassociation of nickel-citrate complex approach was performed to synthesize ultra-small Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles with different average sizes (3.3, 3.7, 4.4, 6.0, 6.3, 7.9, 9.4, 10.0 and 12.2 nm). The best electrochemical performance was observed with a specific capacity of 406 C g−1, an excellent rate capability was achieved at a critical size of 7.9 nm and a rapid decrease in the specific capacity was observed when the particle size was <7.9 nm. This result is because of the quantum confinement effect, which decreased the electrical conductivity and the sluggish charge and proton transfer. The results presented here provide a new insight into the nanosize effect on the electrochemical performance to help design advanced energy storage devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently, electrochemical energy storage devices, such as batteries and supercapacitors, have attracted great attention because of their many advantages compared with other power-source technologies. However, these devices could realize further gains in energy and power densities if the electrochemical performance of electrode materials is largely improved.1, 2 Reducing the dimensions of electrode materials down to the nanoscale level is an effective strategy to promote their electrochemical performance, which primarily benefits from the nanosize effect, that is, achieving a higher surface area and a shorter ion diffusion length.3, 4 In this context, various nanosize electrode materials with greatly improved electrochemical performance have been synthesized.5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Thereupon a fundamental question arises: do smaller electrode materials exhibit better electrochemical performance?

According to the relationship between the band gap (Eg) and the size (a) of a nanoparticle (for semiconductor) defined by [Equation (1)]10, 11, 12

(where Ebulk is the bulk band gap, ΔE is related to the quantum confinement effect, me* is the effective mass of an electron, mh* is the effective mass of a hole and h is Plank’s constant), the band gap increases as the particle size reduces. It should be noted that the quantum confinement effect, a sort of nanosize effect, inevitably arises as the particle size reduces to the nanoscale, particularly when <10 nm.10, 11, 12 Furthermore, we deduced the relationships between particle size, conductivity (σ) and ΔE (Equation (2) and Equation (3))

(σo represents the conductivity of the bulk-state semiconductor, kB is the Boltzmann constant, q is a constant related to me* and mh*), which are plotted in Figure 1 (additional details regarding this deduction are shown in Supplementary Information). The widening of the band gap is closely related to the quantum confinement effect, which decreases σ (Figure 1a), and a dramatic decrease in σ occurs as the particle size reduces to an extent (shadow region in Figure 1b). Importantly, most works have proved that σ is closely related to the ion diffusional limitation and the polarization loss for electrode materials, where a decrease in σ causes an inferior electrochemical performance of electrode materials.10, 13, 14, 15, 16 Inspired by the above analyses, we hypothesize that minimizing the particle size may have a negative effect on the electrochemical performance, such that a critical size should exist for electrode materials. In addition, while many nanomaterials used in electrochemical energy storage devices have been synthesized by various methods, a precisely size-controlled synthesis and a systematic study of size-dependent electrochemical performance for the electrode materials are rarely performed due to the difficulty in controlling the size, particularly when <10 nm. These reasons have strongly motivated us to explore size-controlled electrode materials to elucidate the nanosize effect on the electrochemical properties for sub-10-nm materials for energy storage applications.

Ni(OH)2, a typical lamellar-type hydroxide, is an important electrode material with a high theoretical capacity and has recently attracted great attention for use in designing high-performance battery and supercapacitor systems.3, 9, 14, 15, 17 Herein, for the first time, a series of ultra-small Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles with tunable sizes ranging from 3.3 to 12.2 nm are prepared via a scalable formation and disassociation of a nickel-citrate complex. These size-controlled Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles overcome the previous size limitation and could be a desirable platform to reveal the nanosize effect on the electrochemical performance of sub-10-nm electrode materials.

Experimental procedure

Synthesis of size-controlled Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles

In a typical synthesis, 0.172 mM of Ni(NO3)2·6H2O and 1.16 mM of C6H5Na3O7·2H2O were first dissolved in 20 ml of distilled water under magnetic stirring. Then, 10 ml of a NaBH4 aqueous solution (0.1 M) was rapidly injected into this mixture with vigorous stirring, which created a black solution. The entire solution was stirred for 10 h at 35 °C to promote the complete oxidation of Ni particles and form stable nickel-citrate species, as observed by the color change of the solution from black to clear green. More details regarding the role of sodium citrate are given in our previous work.18, 19 Afterwards, 5 ml of NaOH aqueous solution (4 M) was added to the mixture immediately. The reaction mixture was continuously stirred for 5 min, then transferred into an autoclave and heated at a given reaction temperature (20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 120, 140, 160 or 180 °C) for 24 h. Finally, a green sediment was obtained, which indicates the formation of Ni(OH)2. The sediment was collected, washed with distilled water by centrifugation at 10 000 r.p.m. and re-dispersed in distilled water for further study.

Structural characterization

A transmission electron microscope (TEM, JEOL 2100 FEG, Tokyo, Japan) was employed to investigate the microstructure of the as-prepared Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles. Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku D/Max-2400, Tokyo, Japan) was performed using Cu-Kα radiation to investigate the structure and composition of the samples. The zeta potential of the Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles dispersed in distilled water was measured with a Zetasizernano 3600 instrument. The Raman spectra of Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles were recorded by using a micro-Raman spectroscope (JY-HR800, Paris, France, excitation wavelength of 532 nm). The UV-vis absorption spectra of Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles in water were recorded on a UV-vis spectrophotometer (Hitachi U-3010, Tokyo, Japan).

Electrode preparation and electrochemical measurements

The working electrodes were prepared as follows: the glassy carbon electrode (gas chromatography, 5 mm in diameter) was polished mechanically to become mirror-like by successively using 50-nm alumina powder, cleaned in an ultrasonic water bath and dried in an oven at 45 °C. Five milliliter of the Ni(OH)2 suspension (2.0 mg ml−1) was ultrasonically mixed with 2 ml of ethanol, 3 ml of distilled water and 0.5 mg of conductive carbon black (XC-72, Cabot, Shanghai, China) to form a homogeneous ink. 10 μl of this ink was deposited onto the surface of the gas chromatography electrode and then dried naturally. Afterwards, 8 μl of diluted Nafion solution (5 wt%) was deposited to fix the active material onto the electrode. For all working electrodes, the same mass loading of ~50 μg cm−2 was used to reduce the effect of the electrode thickness on the electrochemical properties.

Electrochemical measurements were first performed using an electrochemical working station (CHI660D, Shanghai, China) in a three-electrode system in a 2-M KOH aqueous electrolyte at room temperature. A platinum wire electrode and a saturated calomel electrode served as the counter electrode and reference electrode, respectively.

Cyclic voltammetry was applied to study the electrochemical properties and measure the proton diffusion coefficient according to the Randles–Sevcik equation:20

where Ip is the peak current, n is the electron number of the reaction (approximately 1 for Ni(OH)2), F is Faraday’s constant, S is the real surface area of the electrode, R is the ideal gas constant, T is the temperature, D is the diffusion coefficient, v is the scanning rate and c0 is the initial concentration of the reactant.

Results and Discussion

Morphology and structural characterization

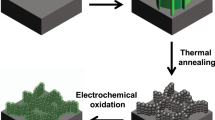

Figure 2a–c and Supplementary Figure S1 show that ultra-small, crystalline Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles were synthesized on a large scale via the formation and disassociation of a nickel-citrate complex process with high yields (exceeding 92%, more details in Supplementary Information). The lattice fringes of the Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles with an average spacing of ~0.24 nm can be indexed as the (101) plane (Figure 2b). The merit of this approach is the ability to synthesize size-controlled Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles by adjusting the reaction temperature from 20 to 180 °C, which was confirmed by TEM images (Figure 2d–l, Supplementary Figures S2 and S3). The morphology of the smaller Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles synthesized at a lower reaction temperature (less than 80 °C) is irregular (Figure 2d and Supplementary Figure S2), whereas a platelet-like morphology is obtained in the larger sized Ni(OH)2 prepared at higher reaction temperatures (>80 °C) (Figure 2h–l and Supplementary Figure S3). It should be noted that several bar-like particles exist in larger sized Ni(OH)2 synthesized at a higher reaction temperature. The difference in morphology of the Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles may be due to the placing of particles in different directions, where the platelet-like morphology is related to an upward (100) facet of Ni(OH)2 and the bar-like morphology is related to an upward (001) facet of Ni(OH)2 (more details are given in Supplementary Figure S3).

(a) Schematic diagram of the synthetic route of Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles via the facile formation and disassociation of nickel-citrate complex. (b) A typical transmission electron microscopy image of Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles synthesized at 20 °C; inset: transmission electron microscopy image showing an individual Ni(OH)2 nanocrystalline. (c) Optical photograph showing that large-scale Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles (~10 g) can be prepared in a 3-l beaker at 20 °C. Transmission electron microscopy images of as-synthesized Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles prepared at different temperatures: (d) 20 °C, (e) 40 °C, (f) 60 °C, (g) 80 °C, (h) 100 °C, (i) 120 °C, (j) 140 °C, (k) 160 °C and (l) 180 °C.

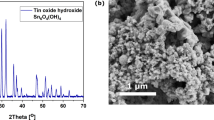

Figure 3a shows the XRD patterns of the Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles of different sizes. All XRD diffraction peaks can be indexed as a hexagonal phase β-Ni(OH)2 (space group P-3m1(164), a=b=0.313 nm, c=0.463 nm, JCPDS 14-0117) without showing any impurity phase. Such hexagonal β-Ni(OH)2 can be depicted as a lamellar structure, where NiO6 octahedra are separated by hydrogen atoms (Figure 3b).17 Moreover, the broadening of the XRD peaks, particularly for the samples prepared at low reaction temperatures (<80 °C), indicates the presence of ultra-small crystalline sizes for Ni(OH)2, which is also supported by the clear presence of lattice fringe observed in the TEM images (Figure 2b inset, and Supplementary Figures S2 and S3). The particle sizes of the β-Ni(OH)2 samples were estimated by the Scherrer equation to be ~3.3, ~3.7, ~4.4, ~6.0, ~6.3, ~7.9, ~9.4, ~10.0 and ~12.2 nm, respectively. An almost linear relation between the particle size of Ni(OH)2 and the reaction temperature is observed (Figure 3c), which indicates that the particle size of Ni(OH)2 could be well controlled by the reaction temperature. Note that there is a difference in particle size values estimated from XRD and TEM, as shown in Supplementary Table S1, which can be ascribed to the hexagonal lamellar structures of Ni(OH)2 (more details given in Supplementary Figure S3).

(a) X-ray diffraction patterns of Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles with different particle sizes. (b) Lamellar structure of Ni(OH)2. (c) A linear relationship between the particle size of Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles and the synthesis temperature. The solid red line is the fitting line. (d) Selected Raman spectra of Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles with different sizes. (e) Full-width at the half-maximum value at the peak of 3580 cm−1 is as a function of the reciprocal particle size (1/a). (f) Optical photographs showing the transparent green Ni(OH)2 gels. Inset shows that the green gels can be picked up easily by chopsticks. (g) A colloidal Ni(OH)2 in aqueous solution indicated by the Tyndall scattering effect via a red laser beam. (h) UV spectra of Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles with different sizes. Inset shows the band gap calculated from the UV spectra results.

Figure 3d and Supplementary Figure S4 show selected regions of the Raman spectra for nanocrystalline Ni(OH)2 with different sizes, ranging from 3.3 to 12.2 nm. Three identified Raman peaks at ~310, ~450 and ~3580 cm−1 are observed, which can be assigned to the E-type vibration of the Ni-OH lattice, Ni-O stretching (vNi-O) and symmetric stretching of the hydroxyl groups (vOH), respectively.21 The full-width at the half-maximum values of these peaks, particularly at 3580 cm−1, increase as the particle size decreases (Figure 3e). This phenomenon is also observed in other works on Ni(OH)2,22 LiCoO223 and MoS224 with different particle sizes. Moreover, no clear peak appears at ~3680 cm−1, which is generally assigned to free -OH groups on the surface, impurities, crystal defects and OH stretching for a new crystal phase, which indicates the good crystallized structure of the as-prepared Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles.21 This result is consistent with the aforementioned TEM results. Interestingly, high concentrations of the Ni(OH)2 dispersion (reaction temperature at 20 °C) turned into a transparent green gel (Figure 3f) after 12 h of standing. The green gel can be laid flat and inverted into a beaker and can be picked up easily by chopsticks (Supplementary Figure S5 and Figure 3f inset). Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles can also be homogeneously dispersed in water to form a transparent green colloid at low concentrations (Figure 3g). The colloidal state of Ni(OH)2 in the aqueous solution was confirmed by observing the Tyndall scattering effect when passing a red laser beam through the solution (Supplementary Figure S6). The Ni(OH)2 colloids (reaction temperature <100 °C) can be stable for over half a year because of their negative zeta potential (Supplementary Figure S7) or ultra-small particle sizes. Figure 3h shows the UV-visible spectra of Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles dispersed in water. The steep absorption in the UV spectra below 350 nm is attributed to the band gap absorption of the Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles. As seen in inset of Figure 3h, smaller Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles have larger band gap values. Such a size-dependent blue shift in the band gap energy of the Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles can be attributed to the quantum confinement effect,10, 11, 12 which also has been observed in various semiconductor quantum dots or nanofilms, which include ZnO,11 CdS,25 CdSe26 and InAs.27

Electrochemical characterization

The electrochemical response of these different sized Ni(OH)2 was characterized using cyclic voltammetry and galvanostatic discharge/charge in 2 M KOH. For all of the Ni(OH)2 electrodes, one pair of redox peaks is located on their cyclic voltammetry curves, as shown in Figure 4a, which indicates that the capacity response is primarily due to the Faradaic redox reaction of Ni2+ to Ni3+. A larger potential difference between the oxygen-evolution-reaction potential (Eo) and anodic peak (Ea) and a smaller potential difference between Ea and the cathodic peak (Ec) can be observed in the smaller Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles (Supplementary Table S2), which indicate better reversibility and a higher charge efficiency.28 Figure 4b shows the discharge curves for Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles at 1 A g−1. Each discharge profile is composed of two sloping potential regions (greater than 0.22 V and less than 0.15 V) and a battery-type potential plateau between 0.15 and 0.22 V. The sloping regions can be ascribed to the pseudocapacitive contribution from surface or near-surface layer charge storage.23 The battery-type potential plateau in all discharge curves is greatly related to the redox action between the Ni(OH)2 and NiOOH phase. Notably, the proportion of the sloping region increased as the size of the Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles decreased, which became clearer at the high discharge current density of 20 A g−1 (Figure 4c and Supplementary Figure S8). To a certain extent, the proportion of the sloping region increases with a decrease in size, which indicates the increased pseudocapacitive behavior due to the nanosize effect on the surface reaction.23, 29 Such a nanosize effect on the electrochemical property of Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles is also indicated by the lower redox voltage of Ni2+ to Ni3+ (Figure 4a and Supplementary Table S2) and steeper charge curves for smaller Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles (Supplementary Figure S9).

(a) Cyclic voltammetry curves of Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles of different sizes at a scan rate of 20 mV s−1. (b) Galvanostatic discharge curves of these Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles at a current density of 1 A g−1. (c) Slope region proportion for different sized Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles in the total discharging region at current densities of 1 and 20 A g−1, respectively. (d) Specific capacity of Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles of different sizes as a function of the discharge current density.

Figure 4d shows the specific capacity of these different sized Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles as a function of discharge current density. The traditional concept of how particle size affects the specific capacity of electrode materials is that smaller particles exhibit better electrochemical performance. Therefore, it is expected that 3.3-nm Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles will exhibit the highest electrochemical performance. Indeed, decreasing the average size from 12.2 to 7.9 nm causes a gradual increase in the capacity value (from 243 to 406 C g−1 at 1 A g−1), as expected. However, the opposite trend is observed in the specific capacity as the particle size continues to decrease. With a decrease in the particle size from 7.9 to 3.3 nm, the specific capacity decreases rapidly from 406 to 224 C g−1 at 1 A g−1. When the discharge current density further increases to 20 A g−1, the same trend is observed. Accordingly, the optimal electrochemical performance is obtained at a critical size of 7.9 nm, not at 3.3 nm, which cannot be explained by the traditional understanding.

These results are particularly interesting; however, it is still unclear what causes this reverse trend and how it affects the electrochemical performance. To make this clear, we first investigate the relationship between the conductivity, band gap and particle size of the Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles. UV spectroscopy (Figure 3h inset) shows that smaller Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles have a larger blue shift of the band gap (ΔE) due to the quantum confinement effect. According to the relationship in Figure 1a, with a decrease in the particle size from 12.2 to 7.9 nm, the band gap increases ~0.08 eV, which leads to the conductivity decreasing by ~4.75 times. As the particle size decreases from 7.9 to 3.3 nm, the band gap shifts ~0.27 eV, resulting in a decrease in conductivity by ~166 times. Weidner et al. suggested that the rapid decrease in conductivity causes a significant polarization loss via the theoretical simulation of the discharge character of Ni(OH)2.30, 31, 32 In our study, at a particle size that is less than the critical value (7.9 nm), there is a decrease in capacity as the particle size decreases, which corresponds to a rapid decrease in conductivity; this result demonstrates the role of conductivity in the electrochemical performance. Moreover, many works have proven that the conductivity of electrode materials is closely related to the diffusion of protons through the nanoparticle and the redox reaction rate on the surface.10, 13, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35 This result leads us to hypothesize that the charge transfer resistance (Rct) and proton diffusion coefficient (D) in the electrodes and electrolytes could change and differ from the traditional understanding because the particle size of Ni(OH)2 is less than the critical size.

To prove this, the Rct and D of these size-tunable Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles were tested. As shown in Figure 5a, the diameter of the semi-circle in the high-frequency region of the electrical impedance spectra is ascribed to Rct. An equivalent circuit was used to simulate the electrical impedance spectra curves, and the corresponding parameters are summarized in Supplementary Figure S10 and Supplementary Table S3. There is a trend of decreasing Rct values when the particle size decreases from 12.2 to 7.9 nm (Figure 5b). However, at a particle size of less than a critical value (7.9 nm), the trend reverses, and there is a rapid increase in Rct, which indicates the slow kinetics of the redox reaction of Ni(OH)2. In addition, the redox reaction for Ni(OH)2 is widely recognized as a typical proton (H) controlled diffusion; thus, the proton diffusion coefficient (D) can be calculated from the Randles-Sevcik equation (Supplementary Figure S11).36, 37 Figure 5c shows that the trend of D manifests the inverse behavior with Rct. There is an increase in D as the particle size decreases from 12.2 to 7.9 nm; however, a sharp decrease in D is observed when the particle size is less than 4.4 nm. The decrease of D in small electrode materials for a Li-ion battery, such as Li4Ti5O12 and TiO2, was also reported recently.38, 39 As we know, the enlarged proton diffusion limitation and increased charge transfer resistance will lead to a great degree-of-discharge at the surface, and a larger overpotential is required to maintain a constant-current discharge.23 Therefore, a small D and a large Rct value will decrease the use of active materials, resulting in an inferior electrochemical performance. In our study, decreasing the particle size from 12.2 to 7.9 nm caused a slight increase in D and a decrease in Rct, which is identical to the traditional nanosize concept, where nanosizing is used to increase the active surface area and reduce the diffusion path of protons and electrolyte ions. As expected, an increase in capacity is observed. In contrast, a reverse trend in Rct and D is observed as the size of the Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles further decreases below 7.9 nm, and a decrease in the capacity occurs. It should be noted that this reverse trend in Rct and D is synchronized with the rapidly decreasing trend in σ caused by the quantum confinement effect, which is consistent with other reports10, 13, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35 and confirms the underlying relationship between σ, Rct and D. As a result, 3.3-nm Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles have a minimum capacity value because of their low conductivity, large charge transfer resistance and small proton diffusion coefficient.

(a) Electrical impedance spectra spectra of Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles with different sizes. (b) Charge transfer resistance (Rct) for Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles. (c) Diffusion coefficient values of Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles with different sizes. (d) Model depicting the relationship between the impact factors and particle size in the discharging process of Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles.

Generally speaking, three steps are involved in the redox reaction of Ni(OH)2 in an alkaline solution: the diffusion of the electrolyte to the electrode surface, the intercalation/deintercalation of protons and the electron transfer in/out of the Ni(OH)2 electrode.35, 36, 37 Accordingly, a simple model that considers the relationship between the above stated parameters (σ, Rct and D) and electrochemical performance is proposed to explain the nanosize effect on these Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles with tunable sizes, as shown in Figure 5d. Extreme reductions in the particle size to less than 7.9 nm decreases the electrochemical performance of Ni(OH)2, which can be ascribed to the quantum confinement effect for the decreased electrical conductivity and the sluggish charge and proton transfer. When the particle size is greater than 7.9 nm, the decreased electrochemical performance of Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles is observed due to the increasing charge and proton transfer resistance. A critical size (7.9 nm), which is where the best electrochemical performance is obtained, exists for Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles, which would largely account for the synergistic effect from the low charge and proton resistance as well as the acceptable electrical conductivity.

Conclusions

In summary, size-controlled Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles overcome the previous limitation in synthesizing size-controlled electrode materials less than 10 nm in size and are a desirable platform to study the nanosize effect on electrochemical performance. The maximum capacity value can be obtained at the critical size of ~7.9 nm, and a rapid decrease in the specific capacity is observed when the extremely reduced size is less than the critical size. Clearly, the nanosize effect on Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles presented here is different from the popular concept, that is, that below the critical size, smaller Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles have a lower capacity due to the quantum confinement effect from the decreased conductivity and sluggish charge and proton transfer. Thus, this work helps in understanding the nanosize effect on electrochemical behaviors and provides valuable information for selecting appropriately sized electrode materials to design high-performance energy storage devices.

References

Simon, P. & Gogotsi, Y. Materials for electrochemical capacitors. Nat. Mater. 7, 845–854 (2008).

Dunn, B., Kamath, H. & Tarascon, J.-M. Electrical energy storage for the grid: a battery of choices. Science 334, 928–935 (2011).

Augustyn, V., Simon, P. & Dunn, B. Pseudocapacitive oxide materials for high-rate electrochemical energy storage. Energy Environ. Sci 7, 1597–1614 (2014).

Balaya, P. Size effects and nanostructured materials for energy applications. Energy Environ. Sci. 1, 645–654 (2008).

Kim, H., Seo, M., Park, M. H. & Cho, J. A critical size of silicon nano-anodes for lithium rechargeable batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 49, 2146–2149 (2010).

Yu, M., Wang, W., Li, C., Zhai, T., Lu, X. & Tong, Y. Scalable self-growth of Ni@NiO core-shell electrode with ultrahigh capacitance and super-long cyclic stability for supercapacitors. NPG Asia Mater. 6, e129 (2014).

Wang, B., Chen, J. S., Wang, Z., Madhavi, S. & Lou, X. W. Green synthesis of NiO nanobelts with exceptional pseudo-capacitive properties. Adv. Energy Mater 2, 1188–1192 (2012).

Lu, X., Yu, M., Wang, G., Zhai, T., Xie, S., Ling, Y., Tong, Y. & Li, Y. H-TiO2@MnO2//H-TiO2@C core–shell nanowires for high performance and flexible asymmetric supercapacitors. Adv. Mater. 25, 267–272 (2013).

Li, H. B., Yu, M. H., Wang, F. X., Liu, P., Liang, Y., Xiao, J., Wang, C. X., Tong, Y. X. & Yang, G. W. Amorphous nickel hydroxide nanospheres with ultrahigh capacitance and energy density as electrochemical pseudocapacitor materials. Nat. Commun. 4, 1894 (2012).

Son, Y., Park, M., Son, Y., Lee, J. S., Jang, J. H., Kim, Y. & Cho, J. Quantum confinement and its related effects on the critical size of GeO2 nanoparticles anodes for lithium batteries. Nano Lett. 14, 1005–1010 (2014).

Lin, K. F., Cheng, H. M., Hsu, H. C., Lin, L. J. & Hsieh, W. F. Band gap variation of size-controlled ZnO quantum dots synthesized by sol–gel method. Chem. Phys. Lett. 409, 208–211 (2005).

Ponomarenko, L. A., Schedin, F., Katsnelson, M. I., Yang, R., Hill, E. W., Novoselov, K. S. & Geim, A. K. Chaotic dirac billiard in graphene quantum dots. Science 320, 356–358 (2008).

Tang, Y., Zhang, Y., Deng, J., Qi, D., Leow, W. R., Wei, J., Yin, S., Dong, Z., Yazami, R., Chen, Z. & Chen, X. Unravelling the correlation between the aspect ratio of nanotubular structures and their electrochemical performance to achieve high-rate and long-life lithium-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 53, 13488–13492 (2014).

Ji, J., Zhang, L. L., Ji, H., Li, Y., Zhao, X., Bai, X., Fan, X., Zhang, F. & Ruoff, R. S. Nanoporous Ni(OH)2 thin film on 3D ultrathin-graphite foam for asymmetric supercapacitor. ACS Nano 7, 6237–6243 (2013).

Zhou, D., Su, X., Boese, M., Wang, R. & Zhang, H. Ni(OH)2@Co(OH)2 bi-hexagonal nanonuts: controllable synthesis, facet-selected competitive growth and capacitance property. Nano Energy 5, 52–59 (2014).

Zhu, H. & Lian, T. Wave function engineering in quantum confined semiconductor nanoheterostructures for efficient charge separation and solar energy conversion. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 9406–9418 (2012).

Hermet, P., Gourrier, L., Bantignies, J. L., Ravot, D., Michel, T., Deabate, S., Boulet, P. & Henn, F. Dielectric, magnetic, and phonon properties of nickel hydroxide. Phys. Rev. B 84, 235211 (2011).

Wang, R. T., Kong, L. B., Lang, J. W., Wang, X. W., Fan, S. Q., Luo, Y. C. & Kang, L. Mesoporous Co3O4 materials obtained from cobalt–citrate complex and their high capacitance behavior. J. Power Sources 217, 358–363 (2012).

Wang, R. & Yan, X. Superior asymmetric supercapacitor based on Ni-Co oxide nanosheets and carbon nanorods. Sci. Rep. 4, 3712 (2014).

Wang, X. Y., Yan, J., Zhang, Y. S., Yuan, H. T. & Song, D. Y. Cyclic voltammetric studies of pasted nickel hydroxide electrode microencapsulated by cobalt. J. Appl. Electrochem. 28, 1377–1387 (1998).

Hall, D. S., Lockwood, D. J., Poirier, S., Bock, C. & MacDougall, B. R. Raman and infrared spectroscopy of α and β phases of thin nickel hydroxide films electrochemically formed on nickel. J. Phys. Chem. A 116, 6771–6784 (2012).

Audemer, A., Delahaye, A., Farhi, R., Sac-Epée, N. & Tarascon, J. M. Electrochemical and raman studies of beta-type nickel hydroxides Ni1 − xCox(OH)2 electrode materials. J. Electrochem. Soc. 144, 2614–2620 (1997).

Okubo, M., Hosono, E., Kim, J., Enomoto, M., Kojima, N., Kudo, T., Zhou, H. & Honma, I. Nanosize effect on high-rate li-Ion intercalation in LiCoO2 electrode. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 7444–7452 (2007).

Gopalakrishnan, D., Damien, D. & Shaijumon, M. M. MoS2 quantum dot-interspersed exfoliated MoS2 nanosheets. ACS Nano 8, 5297–5303 (2014).

Baskoutas, S. & Terzis, A. F. Size-dependent band gap of colloidal quantum dots. J. Appl. Phys. 99, 013708 (2006).

Norris, D. J. & Bawendi, M. G. Measurement and assignment of the size-dependent optical spectrum in CdSe quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 53, 16338 (1996).

Tian, Y., Sakr, M. R., Kinder, J. M., Liang, D., MacDonald, M. J., Qiu, R. L. J., Gao, H. J. & Gao, X. P. A. One-dimensional quantum confinement effect modulated thermoelectric properties in InAs nanowires. Nano Lett. 12, 6492–6497 (2012).

Li, W., Zhang, S. & Chen, J. Synthesis, characterization, and electrochemical application of Ca(OH)2-, Co(OH)2-, and Y(OH)3-coated Ni(OH)2 tubes. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 14025–14032 (2005).

Wang, J., Polleux, J., Lim, J. & Dunn, B. Pseudocapacitive contributions to electrochemical energy storage in TiO2 (anatase) nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C 111, 14925–14931 (2007).

Weidner, J. W. & Timmerman, P. Effect of proton diffusion, electron conductivity, and charge-transfer resistance on nickel hydroxide discharge curves. J. Electrochem. Soc. 141, 342–346 (1994).

Barnard, R., Randell, C. F. & Tye, F. L. Studies concerning charged nickel hydroxide electrodes I. Measurement of reversible potentials. J. Appl. Electrochem. 10, 109–125 (1980).

Motupally, S., Streinz, C. C. & Weidner, J. W. Proton diffusion in nickel hydroxide: prediction of active material utilization. J. Electrochem. Soc 145, 29–34 (1998).

Zhou, W., Cao, X., Zeng, Z., Shi, W., Zhu, Y., Yan, Q., Liu, H., Wang, J. & Zhang, H. One-step synthesis of Ni3S2 nanorod@Ni(OH)2 nanosheet core–shell nanostructures on a three-dimensional graphene network for high-performance supercapacitors. Energy Environ. Sci. 6, 2216–2221 (2013).

Xie, J., Sun, X., Zhang, N., Xu, K., Zhou, M. & Xie, Y. Layer-by-layer β-Ni(OH)2-graphene nanohybrids for ultraflexible all-solid-state thin-film supercapacitors with high electrochemical performance. Nano Energy 2, 65–74 (2013).

Zhao, J., Chen, J., Xu, S., Shao, M., Zhang, Q., Wei, F., Ma, J., Wei, M., Evans, D. G. & Duan, X. Hierarchical NiMn layered double hydroxide/carbon nanotubes architecture with superb energy density for flexible supercapacitors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 2938–2946 (2014).

Okubo, M., Mizuno, Y., Yamada, H., Kim, J., Hosono, E., Zhou, H., Kudo, T. & Honma, I. Fast Li-Ion insertion into nanosized LiMn2O4 without domain boundaries. ACS Nano 4, 741–752 (2010).

Duan, X., Kiani, M. A., Mousavi, M. F. & Ghasem, S. Size effect investigation on battery performance: comparison between micro and nano-particles of β-Ni(OH)2 as nickel battery cathode material. J. Power Sources 195, 5794–5800 (2010).

Kavan, L., Procházka, J., Spitler, T. M., Kalbáč, M., Zukalová, M., Drezen, T. & Grätzel, M. Li insertion into Li4Ti5O12 (spinel): charge capability vs. particle size in thin-film electrodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 150, A1000–A1007 (2003).

Shen, K., Chen, H., Klaver, F., Mulder, F. M. & Wagemaker, M. Impact of particle size on the non-equilibrium phase transition of lithium-inserted anatase TiO2 . Chem. Mater. 26, 1608–1615 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Defense Basic Research Program of China and the National Nature Science Foundations of China (21203223).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the NPG Asia Materials website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, R., Lang, J., Liu, Y. et al. Ultra-small, size-controlled Ni(OH)2 nanoparticles: elucidating the relationship between particle size and electrochemical performance for advanced energy storage devices. NPG Asia Mater 7, e183 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/am.2015.42

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/am.2015.42

This article is cited by

-

Structural, optical and humidity sensing studies of nickel oxide (NiO) nanoparticles: effect of calcination temperature

Chemical Papers (2024)

-

Preparation of electrochromic nickel hydroxide (II) thin film by drying sol obtained by dialysis of solution with precipitate formed from nickel nitrate aqueous solution with ammonia and sorbitol

Journal of Sol-Gel Science and Technology (2023)

-

Activation of nitrogen species mixed with Ar and H2S plasma for directly N-doped TMD films synthesis

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Tuning the antimicrobial efficacy of nano-Ca(OH)2 against E. coli using molarity

Journal of Materials Science (2022)

-

Fabrication of Ni Nanoparticle-Embedded Porous Carbon Nanofibers Through Selective Etching of Selectively Oxidized MgO

Electronic Materials Letters (2022)