Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

Our primary objective was to examine the relationship between umbilical arterial gas analysis and decision-to-delivery interval for emergency cesareans performed for nonreassuring fetal status to determine if this would validate the 30-minute rule.

STUDY DESIGN:

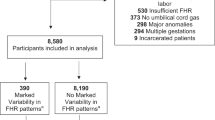

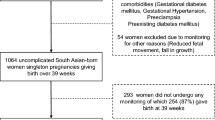

For this retrospective cohort study, all cesarean deliveries performed for nonreassuring fetal status from September 2001 to January 2003 were reviewed. A synopsis of clinical information that would have been available to the clinician at the time of delivery and the last hour of the electronic fetal heart rate tracing prior to delivery were reviewed by three different maternal–fetal medicine specialists masked to outcome, who classified each delivery as either emergent (delivery as soon as possible) or urgent (willing to wait up to 30 minutes for delivery) since immediacy of the fetal condition is the key factor affecting the type of anesthesia used.

RESULTS:

Of 145 cesareans performed for nonreassuring fetal status during this period, 117 patients met criteria for entry, of which 34 were classified as emergent and 83 as urgent. Kappa correlation was 0.35, showing only fair/moderate agreement between reviewers. In the emergent group, general anesthesia was more common (35.3%, 10.8%, p=0.003), and the decision-to-delivery interval was 14 minutes shorter (23.0±15.3, 36.7±14.9 minutes, p<0.001). Linear regression showed a statistically significant relationship between increasing decision-to-delivery interval and umbilical arterial pH (r=0.22, p=0.02) and base excess (r=0.33, p<0.001) showing that delivery proceeded sooner for most of those with the worst cord gases, with a gradual improvement over time. For the 13 (11%) neonates with cord gases placing them at increased risk for long-term neurologic sequelae, the decision-to-delivery interval was 24.7±14.6 minutes (range 6 to 50 minutes), and 3/13 (23%) were classified as urgent rather than emergent.

CONCLUSION:

Electronic fetal monitoring shows considerable variation in interpretation among maternal–fetal medicine specialists and is not a sensitive predictor of the fetus developing metabolic acidosis. There is no deterioration in cord gas results after 30 minutes, and most neonates delivered emergently or urgently for nonreassuring fetal status even when born after 30 minutes have normal cord gases. The 30-minute rule is a compromise that reflects the time it takes the fetus to develop severe metabolic acidosis, our imprecision in its identification, and its rarity in the presence of nonreassuring fetal monitoring.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Intrapartum and Postpartum care of Women. Guidelines for Perinatal Care. Elk Grove Village, IL: AAP; Washington, DC: ACOG; 2002. p. 125–161.

Halsey H, Douglas R . Fetal distress and fetal death in labor. Surg Clin North Am 1957;37:421–434.

Choate J, Lund C . Emergency cesarean section. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1968;100:703–715.

Shiono PH, Fielden JG, McNellis D, Rhoads GG, Pearse WH . Recent trends in cesarean birth and trial of labor rates in the United States. JAMA 1987;257:494–497.

Goldaber KG, Gilstrap III LC, Leveno KJ, Dax JS, McIntire DD . Pathologic fetal acidemia. Obstet Gynecol 1991;78:1103–1107.

Low JA, Lindsay BG, Derrick EJ . Threshold of metabolic acidosis associated with newborn complications. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1997;177:1391–1394.

Ross MG, Gala R . Use of umbilical artery base excess: algorithm for the timing of hypoxic injury. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;187:1–9.

Riley RJ, Johnson JWC . Collecting and analyzing cord blood gases. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1993;36:13–23.

Sibanda J, Beard RW . Influence on clinical practice of routine intra-partum fetal monitoring. Br Med J 1975;3:341–343.

Amato JC . Fetal heart rate monitoring. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1983;147:967–969.

Thacker SB, Stroup DF, Peterson HB . Efficacy and safety of intrapartum electronic fetal monitoring: an update. Obstet Gynecol 1995;86:613–620.

Shy KK, Luthy DA, Bennett FC, et al. Effects of electronic fetal-heart-rate monitoring, as compared with periodic auscultation, on the neurologic development of premature infants. N Engl J Med 1990;322:588–593.

Nelson KB, Dambrosia JM, Ting TY, Grether JK . Uncertain value of electronic fetal monitoring in predicting cerebral palsy. N Engl J Med 1996;334:613–618.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion. Inappropriate Use of the Terms Fetal Distress and Birth Asphyxia. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists: Washington, DC; 1998, p. 122–123.

Chauhan SP, Magann EF, Scott JR, Scardo JA, Hendrix NW, Martin JN . Emergency cesarean delivery for nonreassuring fetal heart rate tracings. J Reprod Med 2003;48:975–981.

Roberts SW, Leveno KJ, Sidawi JE, Lucas MJ, Kelly MA . Fetal acidemia associated with regional anesthesia for elective cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 1995;85:79–83.

Mueller MD, Bruhwiler H, Schupfer GK, Luscher KP . Higher rate of fetal acidemia after regional anesthesia for elective cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 1997;90:131–134.

Dyer RA, Els I, Farbas J, Torr GJ, Schoeman LK, James MF . Prospective, randomized trial comparing general with spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery in preeclamptic patients with a nonreassuring fetal heart trace. Anesthesiology 2003;99:561–569.

Leung AS, Leung EK, Paul RH . Uterine rupture after previous cesarean delivery: maternal and fetal consequences. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1993;169:945–950.

Hawkins JL, Koonin LM, Palmer SK, Gibbs CP . Anesthesia-related deaths during obstetric delivery in the United States, 1979–1990. Anesthesiology 1997;86:277–284.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Statistical Consultant: Elizabeth A. Johnson, MS, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Biostatistics Department, Johns Hopkins University, USA.

Presented at the annual meeting of the Society of Obstetrical Anesthesia and Perinatology, Phoenix, AZ, USA, May 14–17, 2003.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Holcroft, C., Graham, E., Aina-Mumuney, A. et al. Cord Gas Analysis, Decision-to-Delivery Interval, and the 30-Minute Rule for Emergency Cesareans. J Perinatol 25, 229–235 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jp.7211245

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jp.7211245

This article is cited by

-

Cord Blood Gas Analysis

Journal of Perinatology (2005)

-

Cord Gas Analysis, Decision-to-Delivery Interval and the 30-Minute Rule for Emergency Cesareans

Journal of Perinatology (2005)