Abstract

Aims

To report five cases of gonococcal keratoconjunctivitis with severe corneal involvement treated with therapeutic keratoplasty.

Design

Retrospective case series.

Methods

Five consecutive cases of gonococcal keratoconjunctivitis treated with keratoplasty for corneal perforation, with a mean age of 21.2 years, were analysed by patient's history, surgical approaches, and clinical outcomes, corrected visual acuity at initial visit and last follow-up.

Results

All adult cases were originally diagnosed as epidemic keratoconjunctivitis by elsewhere, and corneal perforation occurred with a mean duration of 11 days after development of conjunctivitis. While laboratory tests revealed Neisseria gonorrhoeaein all five cases, three patients showed resistance to ofloxacin. Intensive medical treatment using penicillins and/or cephems was initiated. Two patients had peripheral corneal perforations, one had a paracentral perforation, and another, a large corneal perforation with stromal melting. One case had a central microcorneal perforation. In all cases, the anterior chamber was flat. Corneal perforations were treated with lamellar or penetrating keratoplasty using cryopreserved or fresh corneal grafts. All grafts remained clear during the mean follow-up period of 34.9 months. Final best-corrected visual acuity ranged from 20/60 to 20/16.

Conclusions

Severe gonococcal keratoconjunctivitis can benefit from intensive surgical and medical intervention resulting in satisfactory visual rehabilitation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neisseria gonorrhoeae is one of the most common causes of sexually transmitted disease. Owing to public health intervention, the incidence of gonococcal infection showed a decline from the mid-1970s onwards. Recently, however, it has shown an increase in various areas around the world, including Japan, especially among young people.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 N. gonorrhoeae can cause vision-threatening corneal involvement, resulting in scarring and possible perforation. A proper diagnosis is vital if this is to be avoided, as the clinical outcome of gonococcal keratoconjunctivitis depends on its level of severity at the commencement of the appropriate therapy.6, 7, 8

Ocular gonococcal infection is relatively rare, and during its early stage of development, the resulting keratoconjunctivitis may be attributed to other pathogens, thus delaying a proper clinical diagnosis. Furthermore, N. gonorrhoeae has recently shown increased resistance to antimicrobial agents.1, 2, 4, 9, 10, 11 Such delays in attaining a correct diagnosis, and increased resistance can result in the development of keratitis with severe corneal involvement.

In this study, we report five cases of gonococcal keratoconjunctivitis with corneal perforation, which were managed by a combination of intensive medical and surgical intervention. The objective of the study was to report the clinical findings and efficacy of this approach.

Patients and methods

Five consecutive cases of gonococcal keratoconjunctivitis with corneal perforation were treated at the Department of Ophthalmology, Tokyo Dental College, between 2001 and 2006. Patients consisted of four adult men and one female child with a mean age of 21.2 years (range: 5–29 years). Cases of gonococcal keratoconjunctivitis successfully treated by medical management alone were not included in this study. A demographic profile of the patients is shown in Table 1. All patients were diagnosed with gonococcal keratoconjunctivitis by detection of N. gonorrhoeae from ocular discharge, using either culture (four cases) or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (1 case).

In all cases, severe corneal involvement and extensive destruction of the cornea and flat anterior chamber were observed at the initial visit to our hospital after medical management. Other strategies including pressure-bandaging and adhesives could not be applicable to reform the anterior chamber because of severe destruction of corneal stroma. Therefore, surgical management was scheduled to eradicate the infection and preserve the integrity of the globe. Postsurgical follow-up was carried out for 13–61 months (mean: 34.9 months).

Results

All adult cases were originally diagnosed as epidemic keratoconjunctivitis by local doctors, and corneal perforation occurred before referral within a mean period of 11 days following development of conjunctivitis. Four cases were presumably infected through sexual contact and the only child was infected by her mother.

Resistance of N. gonorrhoeae

In all cases, N. gonorrhoeae was detected from ocular discharge by laboratory tests. Data on sensitivity to antibiotics were not available in one case. All the other cases (cases 1–4) yielded resistant isolates, with three (cases 1, 2, and 4) showing ofloxacin-resistant isolates and one (case 3) showing vancomycin-resistant isolates.

Medical management

All the adult cases were originally diagnosed as epidemic keratoconjunctivitis, and were initially treated with topical application of levofloxacin eye drops (Cravit®, Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Osaka, Japan) before referral to us, but showed no clinical improvement (Table 2). After visiting our hospital, all were put on an intensive course of antibiotics consisting of topical penicillins and/or cephems, accompanied by intravenous penicillins/cephems chosen based on the results of a sensitivity test carried out at our laboratory (Table 2).

Postoperatively, topical antibiotics were tapered depending on clinical findings. To reduce postoperative inflammation, systemic and topical steroids were administered in all cases.

Surgical management

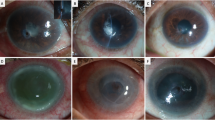

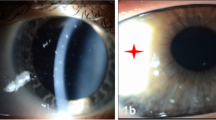

Clinical characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 2, including the size and location of perforation. Corneal perforation occurred within a mean period of 11 days following development of conjunctivitis. In four of five cases (cases 1–4), emergency therapeutic keratoplasty was performed using cryopreserved corneas owing to extensive corneal destruction with stromal melting. All these cases were subjected to lamellar keratoplasty using cryopreserved grafts: lamellar (patch) keratoplasty in cases 1 and 2 (peripheral perforation), deep lamellar keratoplasty in case 3 (paracentral perforation), and corneoscleral keratoplasty in case 4 (large perforation) (Figure 1a and b). Eight months later, the last case also had regrafting using a fresh cornea for visual rehabilitation (Figure 1c).

Case 4: (a) 22-year-old man with subtotal corneal abscess and corneal perforation; (b) therapeutic corneoscleral keratoplasty was performed, and no recurrence of infection was noted; and (c) after 8 months, optical keratoplasty was performed, and patient attained a best-corrected visual acuity of 20/16. Case 5: (d) 5-year-old girl with corneal opacity and progressive corneal thinning; (e) therapeutic and optical keratoplasty was performed, and graft remained clear.

In case 5, the iris was incarcerated in the perforation wound, and there was no obvious leakage of aqueous humour. Therefore, intensive medical treatment was initiated with hospitalization, and the infection was successfully managed. However, as severe corneal opacity and stromal thinning associated with flat anterior chamber caused progressive corneal ectasia, we decided to perform penetrating keratoplasty using a fresh graft for both therapeutic and visual rehabilitation (Figure 1d and e).

Visual outcome and complications

All cases showed clear corneas at the final examination, with a mean follow-up period of 34.9 months (range: 16–61 months). Final visual acuity ranged from 20/60 to 20/16 (mean: 20/20). In case 3, visual acuity was limited to 20/40 due to paracentral corneal scar. In case 5, visual acuity was limited to 20/60 due to the development of a complicated posterior subcapsular cataract.

The postoperative course was uneventful in five patients without recurrence of gonococcal infection. No major complications such as graft failure were noted. In two eyes, secondary glaucoma developed, but intraocular pressure remained within the normal range due to the application of antiglaucomatous eyedrops.

Histopathological examination

Histopathologic examination revealed destruction of stromal structure with fibrosis and various degrees of neutrophil infiltration.

None of the cases showed positive staining for bacteria, which was later confirmed by negative bacterial and fungal culture on excised tissues.

Discussion

Despite effective antimicrobial agents, public health intervention, and efforts to improve health education, gonococcal infection has been on the increase in Japan, especially among young men.12, 13, 14 Most cases of gonococcal keratoconjunctivitis occur in sexually active adults and are transmitted by contact with infected urine or genital secretions, and the increase in gonococcal keratoconjunctivitis seems to be associated with the increase of genital–oral sexual practice.15

Gonococcal keratoconjunctivitis is a potentially devastating infection because of the ability of N. gonorrhoeae to cause severe, ulcerative keratitis, which may rapidly progress to corneal perforation.6, 7, 8 Therefore, it is necessary to obtain an accurate diagnosis and commence parenteral antibiotic treatment as early as possible. However, accurate clinical diagnosis may be delayed due to the relative low incidence of this disease. Indeed, all four adult cases in our series were originally misdiagnosed as epidemic keratoconjunctivitis. Urethral symptoms may precede the ocular symptoms by a period of one to several weeks,10 and retrieval of relevant patient history may help in establishing a correct diagnosis. In our experience, sexually active subjects with hyperacute purulent conjunctivitis or bacterial conjunctivitis refractory to primary antibiotic eyedrops should receive prompt confirmatory cultures for gonococcal organisms and for initiation of early specific antibiotic treatment. In Japan, the new quinolone eyedrops have been used widely. They occupy an approximately 90% market share in antibiotic eyedrops, and are considered to be the first choice for acute conjuncitivitis.12, 16, 17 However, in the last few years, a high prevalence of fluoroquinolone-resistant N. gonorrhoeae isolates has been reported in Japan.1, 2, 4, 9 In addition, N. gonorrhoeae isolates have evolved in acquiring multidrug-resistance not only to fluoroquinolone, but also to penicillin and tetracycline.9, 11 With this rising incidence of -resistant N. gonorrhoeae strains in mind, antibiotics should be chosen carefully and confirmatory sensitivity tests ought to be performed. Among the five cases in this study, four of the isolates were fluoroquinolone-resistant, and initial use of fluoroquinolones may have been responsible for the ensuing rapid corneal involvement.

Corneal perforation constitutes an emergency situation that requires prompt attention in terms of both medical and surgical management if permanent blindness is to be prevented. When corneal perforation does not respond to appropriate medical treatment, other therapeutic approaches including conjunctival flap, amniotic membrane transplantation, and/or tissue adhesive may be considered.18, 19, 20 However, such preservative therapies do not remove infectious pathogens, and cannot be applied to severe keratitis with stromal melting, as noted in our cases. Therefore, we believe that therapeutic keratoplasty is the most effective treatment in such cases.21, 22, 23

We believe that it is better to perform optical keratoplasty after achieving control of infection and inflammation, as severe ocular inflammation at the time of surgery has a negative impact on graft survival. However, most of the cases in this study needed surgical management as soon as possible to avoid secondary endophthalmitis or phthisis, and to control refractory infection and re-establish the structural integrity of the globe.

Faced with such an emergency, lamellar keratoplasty was our first choice to reduce the risk of immunological rejection, endophthalmitis, and secondary glaucoma (cases 1–3).24, 25 With recent improvements in the surgical techniques of keratoplasty, therapeutic keratoplasty has been increasingly successful in managing corneal perforation and refractory corneal inflammation.21, 23, 26 In addition, fresh corneal grafts are not readily available in Japan. Thus, lamellar keratoplasty offers advantages over penetrating keratoplasty for optical purposes. It should be noted that clear grafts cannot be achieved following initial therapeutic keratoplasty in such severe stromal involvement. Secondary regrafting with intensive postoperative management, including immunosuppression, can result in favourable visual rehabilitation, as in case 4.

In summary, we reported five cases of severe corneal perforation secondary to gonococcal keratoconjunctivitis treated by intensive medical and surgical management. Proper diagnosis and intensive antibiotic treatment at an early stage are vital in avoiding irreversible corneal involvement. Therapeutic keratoplasty, especially lamellar keratoplasty when available, appears to be effective in cases with corneal perforation and stromal melting.

References

Tanaka M, Matsumoto T, Sakumoto M, Takahashi K, Saika T, Kabayashi I et al. Reduced clinical efficacy of pazufloxacin against gonorrhea due to high prevalence of quinolone-resistant isolates with the GyrA mutation. The Pazufloxacin STD Group. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1998; 42: 579–582.

Tanaka M, Nakayama H, Haraoka M, Saika T . Antimicrobial resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and high prevalence of ciprofloxacin-resistant isolates in Japan, 1993 to 1998. J Clin Microbiol 2000; 38: 521–525.

Lee JS, Choi HY, Lee JE, Lee SH, Oum BS . Gonococcal keratoconjunctivitis in adults. Eye 2002; 16: 646–649.

Tanaka M, Nakayama H, Notomi T, Irie S, Tsunoda Y, Okadome A et al. Antimicrobial resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Japan, 1993–2002: continuous increasing of ciprofloxacin-resistant isolates. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2004; 24 (Suppl 1): S15–S22.

Little JW . Gonorrhea: update. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2006; 101: 137–143.

Ullman S, Roussel TJ, Culbertson WW, Forster RK, Alfonso E, Mendelsohn AD et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology 1987; 94: 525–531.

Ullman S, Roussel TJ, Forster RK . Gonococcal keratoconjunctivitis. Surv Ophthalmol 1987; 32: 199–208.

Wan WL, Farkas GC, May WN, Robin JB . The clinical characteristics and course of adult gonococcal conjunctivitis. Am J Ophthalmol 1986; 102: 575–583.

The WHO Western Pacific Gonococcal Antimicrobial Surveillance Programme. Surveillance of antibiotic resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the WHO Western Pacific Region, 2004. Commun Dis Intell 2006; 30: 129–132.

Kestelyn P, Bogaerts J, Stevens AM, Piot P, Meheus A . Treatment of adult gonococcal keratoconjunctivitis with oral norfloxacin. Am J Ophthalmol 1989; 108: 516–523.

Matsumoto T, Muratani T, Takahashi K, Ikuyama T, Yokoo D, Ando Y et al. Multiple doses of cefodizime are necessary for the treatment of Neisseria gonorrhoeae pharyngeal infection. J Infect Chemother 2006; 12: 145–147.

Inoue Y . [Treatment of viral conjunctivitis]. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi 2003; 107: 24–26.

Takahashi S, Takeyama K, Kunishima Y, Shimizu T, Nshiyama N, Hotta H et al. Incidence of sexually transmitted diseases in Hokkaido, Japan, 1998 to 2001. J Infect Chemother 2004; 10: 163–167.

Ito M, Yasuda M, Yokoi S, Ito S, Takahashi Y, Ishihara S et al. Remarkable increase in central Japan in 2001–2002 of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates with decreased susceptibility to penicillin, tetracycline, oral cephalosporins, and fluoroquinolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2004; 48: 3185–3187.

Berglund T, Asikainen T, Grutzmeier S, Ruden AK, Wretlind B, Sandstrom E . The epidemiology of gonorrhea among men who have sex with men in Stockholm, Sweden, 1990–2004. Sex Transm Dis 2007; 34: 174–179.

Oishi MH, Hatano H, Abe T, Sasagawa T, Abe H . A nation-wide survey regarding control of infection and use of antimicrobial drugs in eye surgery. Rinsho Ganka 2003; 57: 499–502.

Okamoto S . Bacterial conjunctivitis. Ganka 2003; 45: 843–849.

Weiss JL, Williams P, Lindstrom RL, Doughman DJ . The use of tissue adhesive in corneal perforations. Ophthalmology 1983; 90: 610–615.

Cavanaugh TB, Gottsch JD . Infectious keratitis and cyanoacrylate adhesive. Am J Ophthalmol 1991; 111: 466–472.

Rodriguez-Ares MT, Tourino R, Lopez-Valladares MJ, Gude F . Multilayer amniotic membrane transplantation in the treatment of corneal perforations. Cornea 2004; 23: 577–583.

Hill JC . Use of penetrating keratoplasty in acute bacterial keratitis. Br J Ophthalmol 1986; 70: 502–506.

Claerhout I, Beele H, Van den Abeele K, Kestelyn P . Therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty: clinical outcome and evolution of endothelial cell density. Cornea 2002; 21: 637–642.

Nurozler AB, Salvarli S, Budak K, Onat M, Duman S . Results of therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2004; 48: 368–371.

Shimmura S, Shimazaki J, Tsubota K . Therapeutic deep lamellar keratoplasty for cornea perforation. Am J Ophthalmol 2003; 135: 896–897.

Tong L, Tan DT, Abano JM, Lim L . Deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty in a patient with descemetocele following gonococcal keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol 2004; 138: 506–507.

Sukhija J, Jain AK . Outcome of therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty in infectious keratitis. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging 2005; 36: 303–309.

Acknowledgements

We have received no financial or material support for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Conflict of interest

None.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kawashima, M., Kawakita, T., Den, S. et al. Surgical management of corneal perforation secondary to gonococcal keratoconjunctivitis. Eye 23, 339–344 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6703051

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6703051

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Five-year review of ocular Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections presenting to ophthalmology departments in Greater Glasgow & Clyde, Scotland

Eye (2022)

-

Applying a novel approach to scoping review incorporating artificial intelligence: mapping the natural history of gonorrhoea

BMC Medical Research Methodology (2021)

-

Management of inflammatory corneal melt leading to central perforation in children: a retrospective study and review of literature

Eye (2016)

-

Prevalence of gonococcal conjunctivitis in adults and neonates

Eye (2015)

-

Challenges in the management of Neisseria gonorrhoeae keratitis

International Ophthalmology (2015)