Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the clinical outcomes of corneal grafting for severe dry eye complications in bone marrow transplant recipients.

Methods

Eleven eyes of nine patients with severe corneal complications of chronic graft-versus-host disease were treated from 2000 to 2005. The subjects underwent penetrating keratoplasty (n=9 eyes; seven for perforation and two for leucoma) or deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (n=2 eyes) for deep postinflammatory stromal scarring without endothelial abnormalities. Patients were observed for graft survival, visual acuity, and postoperative complications.

Results

During the follow-up period (mean=21.6 months), nine grafts (82%) remained clear or almost entirely clear and gained more than two logarithmic units of best-corrected visual acuity. Two regrafts were necessary as the primary grafts became cloudy after 9 and 11 months. Persistent epithelial defects occurred in seven eyes (64%), cataract in six (55%), ocular hypertension in five (45%), corneal calcareous degeneration in two (18%), loss of clarity in two (18%), and sterile ulceration in one (9%).

Conclusion

Corneal grafting was effective for restoring corneal clarity and improving visual function in this series of patients. Although the complication ratio was high and some patients required regrafting, there was a clinical improvement in the majority of patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is a serious complication of allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (BMT). It can be classified as acute, occurring within 100 days after BMT, or chronic, usually occurring more than 100 days after BMT. Under pharmacologically induced immunosuppression, acute GVHD occurs in 30–70% of allogeneic bone marrow recipients and in severe cases it is associated with decreased survival. Approximately 30–50% of recipients develop chronic GVHD (cGVHD) preceded by acute GVHD in 90%. Although limited cGVHD resolves spontaneously, extensive cGVHD despite prolonged immunosuppression leads to severe immune dysfunction and death in more than 50% of patients.1 Acute GVHD is believed to develop as a result of a ‘cytokine storm’, whereas cGVHD resembles an autoimmune disease because its essential feature is the overproduction of collagen. Ocular involvement is very common in patients with cGVHD and includes keratoconjunctivitis sicca, cicatrical lagophthalmos, persistent corneal epithelial defect (PED), corneal ulcers, and corneal melting that could lead to perforation and quickly developing endophthalmitis.2, 3, 4, 5, 6 The majority (60–100%) of these patients show evidence of dry eye syndrome, therefore late complications are often severe and rarely amenable to pharmacologic or surgical treatment.7

Materials and methods

Participants

From 2000 to 2005, 11 eyes of nine patients (five men and four women; mean age: 36 years; range: 18–53 years) who had undergone allogeneic BMT were qualified for penetrating or deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty owing to severe dry eye complications in the course of cGVHD. All the patients were referred to our department from Hematology and Bone Marrow Transplantation Clinics. Penetrating keratoplasty (PK) was performed in nine eyes of seven patients (four men and three women) in cases of full-thickness corneal pathology: seven for perforation and two for leucoma. Five perforations were due to sterile ulceration and the direct reason was often trivial (eg, sneeze, yawn), the other two were infectious (Escherichia coli and Acanthamoeba were identified in corneal specimens). Deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty was performed in two eyes of two patients (one man and one woman) for deep post-inflammatory stromal scarring without endothelial abnormalities. Surgery was performed at a mean interval of 14.2±4.6 months after BMT (range, 7–24 months). In two cases, PK was combined with cataract extraction and intraocular lens (IOL) implantation; one of these eyes also underwent keratolimboallograft and amniotic membrane transplantation.

In all cases, both the upper and lower lacrimal puncta were occluded with collagen punctum plugs or by cauterization (in four patients with no reflex tearing, Schirmer I score 1 to 2). Treatment was performed in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki Principle. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before surgery. Institutional review board approval was obtained for this retrospective review and analysis of patient data.

Post-transplant immunosuppression

The standard first-line treatment for cGVHD in all patients was cyclosporine daily and prednisone every other day. Cyclosporine was administered at dosages of 2–4 mg/kg/day starting from the day preceding BMT to day 50, and thereafter slowly tapered until 6 to 12 months after BMT. Prednisone (0.5 mg/kg) was given every other day starting from day 8 and slowly tapered thereafter according to the response. Failure of first-line therapy was defined as no improvement of cGVHD after 3 months of previous treatment or as a progression of cGVHD after 6 weeks. After failure of first-line therapy in three patients, cyclosporine was stopped, and tacrolimus was started at an oral dosage of 0.12 mg/kg/day. Furthermore, four patients received low-dose methotrexate administered intravenously at a dose of 15 mg/m2 on day 1, and then 10 mg/m2 on days 3, 6, and 11 after BMT.

During the follow-up period (mean=21.6 months), one of three patients receiving second-line therapy had discontinued tacrolimus and was in complete remission, another one was considered clinically stable, but not able to discontinue tacrolimus. The other patient died 15 months after BMT.

Surgical technique

The surgery was performed under general anaesthesia. The surgical technique was similar within each of the two groups and all procedures were performed by one surgeon (EW).

Penetrating keratoplasty

In the recipient eye, the cornea including the entire pathologically changed area was trephined using a 7.5–8.0 mm diameter Hessburg–Barron vacuum trephine. In cases of perforation, anterior and/or posterior synechiolysis was performed. The donor button was trephined with a 0.5-mm oversized manual trephine and sutured with 10/0 nylon interrupted sutures (nine eyes), combined running and interrupted sutures (one eye), or double running sutures (one eye). Running sutures were used in two eyes with relatively good visual prognosis, to avoid high-grade astigmatisms. In two eyes, PK was combined with cataract extraction and IOL implantation. In one of these eyes, after the keratoplasty procedure was finished, keratolimboallograft with amniotic membrane transplantation was performed due to limbal stem cell deficiency.

Deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty

In the recipient eye, the cornea was trephined to a depth of 70% with a 7.5-mm diameter Hessburg–Barron vacuum trephine. The stroma was divided into four quadrants using a knife 15° according to Tsubota et al,8 and dissected layer by layer with a crescent knife in the central area of approximately 5 mm in diameter, including the area of the pupil, to the level of Descemet's membrane. The tunnel was then bored out using a spatula. Dissection of the deepest stromal lamellae was performed by injecting a viscoelastic substance through the tunnel into the stromal fibres.

The donor cornea was sutured to the trephination block, and Descemet's membrane together with the endothelium was removed using forceps. The button was then trephined with a 0.5-mm oversized manual trephine, placed onto the recipient bed, and sutured in with a 10/0 nylon single antitorque suture.9

Postoperative proceedings

Patients were reviewed in the clinic at 1 week, 2 weeks, 1 month, and thereafter at 2-month intervals. All received topical fluorochinolone eyedrops (five times a day for a week, and the frequency was then decreased) and topical prednisolone acetate (0.5%) eyedrops four times a day for up to a year, with gradually tapering doses. All the patients needed frequent lubrication with preservative-free artificial tears and/or autologous serum drops administered every 15–30 min.10, 11 In all cases, punctal occlusion with collagen plugs or cauterization was performed at the time of surgery. Collagen plug insertion was repeated at 3- to 4-month intervals, based on the patient's clinical status. Patients who remained symptomatic subsequently underwent cauterization in the both lacrimal puncta of each eye.

Postsurgery systemic therapy for cGVHD was continued according to the haematologist's recommendation and included immunosupressants: prednisone (5–30 mg daily) in all patients and cyclosporine maintained at a serum level of 100–250 ng/ml, or tacrolimus 0.3–0.6 mg/kg/day in patients unresponsive to cyclosporine therapy. Two patients were maintained on prednisone, tacrolimus, and mofetil mycophenolate, and one patient on prednisone, tacrolimus, and methotrexate. The doses were slowly tapered over the following 4–12 months. Systemic antibiotics in the early postoperative period were administered to all patients for control of infections that are highly likely due to the severe immune dysfunction.

Routine blood counts, urine examinations, and kidney and liver function tests were performed monthly. All decisions concerning medication were made in close cooperation with the haematologist.

Data collection

Preoperative data, clinical outcomes, and complications were assessed by one author (DT). Visual acuity, refraction, Schirmer I and II scores, and intraocular pressure were charted. The main outcome measures were graft survival, visual acuity, and development of postoperative complications. A corneal sensitivity test was performed at baseline by touching the patient's central corneal zone with the tip of a cotton swab.12 Corneal sensitivity was considered to be normal if there was a blink reflex when the cornea was touched. If the patient felt contact but had no blink reflex, corneal hypoaesthesia was diagnosed and, if no response was present, corneal anaesthesia was diagnosed. Tear function is presented as Schirmer I and II scores (Table 1). A clear cornea indicated a successful procedure. Corneal surface restoration was defined as epithelialization of the cornea with phenotypic corneal epithelium. Irreversible graft failure was defined as the loss of graft transparency in the central 3 mm due to oedema or surface disorders with or without vascularization.

Results

Preoperative tear function and corneal sensitivity

Eyes with leucoma and corneal opacities (four eyes, 36%) had strongly reduced Schirmer I and II scores as a result of GVHD involving the lacrimal gland.13 In eyes with corneal perforation, Schirmer tests could be unreliable but the scores were always reduced in the concomitant eye. In one patient with large bilateral perforation (Figure 1), the Schirmer test was bilaterally unfeasible. All patients had established subnormal preoperative corneal sensitivity (hypoaesthesia).

Surgical results

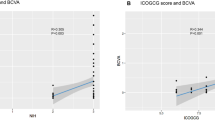

During the follow-up (mean: 21.6 months range, 8–58 months), nine primary grafts (82%) remained clear or partially clear (with a clear central zone) (Figure 2), and these patients gained more than two logarithmic units of best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) (Figure 3). Ambulatory visual acuity, defined according to Solomon et al14 as BCVA ⩾20/200, was achieved in nine eyes. Eight eyes also gained useful near vision (0.5/0.5–3.0/0.5 on Snellen's chart for near vision).

Keratoplasty failed in two eyes (18%) after 9 and 11 months (Cases 3 and 6). One of the failed grafts (Case 3) remained clear for nine months; afterwards, the graft and lens rapidly became cloudy probably as a result of drug toxicity (in the course of pulmonary abscess treatment). Regraft performed in this eye combined with cataract extraction and IOL implantation has remained transparent over the 8-month follow-up. A triple procedure (PK with cataract extraction and IOL implantation) performed for calcareous degeneration in the fellow eye of the same patient was effective (Case 9; Figure 4a and b). In 12 months of follow-up, the graft remained clear with a BCVA of 0.4 (20/50), although this eye developed a paracentral recurrent epithelial defect, which has not yet resolved.

The second regraft was performed for a graft failure caused by sterile ulceration that occurred 11 months after surgery (Case 6), and was followed by full-thickness corneal calcareous degeneration. This second regraft has remained clear in the 6-month follow-up. Regrafted corneas were not included in the data analysis.

In one patient with strongly disturbed limbal efficiency (Case 5), a PK procedure combined with keratolimboallograft with amniotic membrane transplantation was successful and cornea remained clear at the 18-month follow-up.

Complications

The most common postoperative complications were: PED in seven eyes (64%), cataract in six (55%), ocular hypertension in five (45%), corneal calcareous degeneration in one (9%), and sterile ulceration in one (9%).

PED was confirmed when epithelial healing exceeded 4 weeks. It occurred in seven eyes (63%) and healed completely with the exception of one eye that developed ulceration. The maximal epithelial healing period in group was 11 weeks. All seven patients with PED were treated with frequent use of autologous serum drops and artificial tears without preservatives and a moisture chamber; five of the patients with larger defects were also supplied with a bandage contact lens. The smear examination showed no organisms. Patients were followed weekly until the PED was completely healed, and thereafter every month. This treatment was successful in four eyes. In three eyes, the PED exceeded 5–6 weeks, hence these eyes underwent amniotic membrane grafting as the next step in the treatment. Upon completion of the surgery, the eye was covered by a soft bandage contact lens. Despite these efforts, the corneal epithelial defect healed in one and persisted in two eyes for 9 weeks. The central corneal stroma was clear, but infiltrates in the periphery and ciliary injections were observed in both eyes. In these patients, we performed tarsorrhaphy in order to decrease dramatically the desquamation of the corneal epithelium by preventing the mechanical stress of blinking to accelerate wound healing. The epithelial defect began to heal within 1 week in both eyes and in 2 weeks (11 weeks after the keratoplasty) one eye eventually epithelialized and the epithelial defect did not recur for 8 months. In the remaining eye, after the initial improvement, the epithelial wound recurred in 5 weeks, and in the 12-month follow-up, it was observed several times with underlying anterior stromal haze.

Six eyes with perforation developed a cataract that was surgically removed in a later postoperative period in four eyes. Ocular hypertension was observed in five eyes, and was successfully treated by medication in four eyes. One eye that required trabeculectomy to lower intraocular pressure had a stable transparent cornea for 58 months of follow-up with a resultant visual acuity of 0.3 (20/60) (Figure 5).

(Case 1) In right eye at 11 months after PK, we noted increase of IOP that was resistant to medication. Trabeculectomy was effective, but after following 6 months cataract extraction with IOL implantation was necessary for visual rehabilitation. In 58-month follow-up, cornea remained stable and transparent with resultant best-corrected visual acuity of 0.3 (20/60).

Discussion

We reported the efficacy of keratoplasty for the treatment of corneal complications occurring in the course of cGVHD after BMT. To our knowledge, this is the first study assessing the clinical outcomes of keratoplasty performed in such patients.

Ocular symptoms can occur in any stage of GVHD, often causing blindness. Such impaired vision can substantially impact patient activity and makes it difficult to control the basic disease, as patients require frequent follow-up visits at the transplantology clinic in the first year after BMT. The most serious problem in patients with ocular manifestations of cGVHD is severe dry eye. Dry eye after BMT occurs only in allograft recipients and is not evident in autograft recipients. The severe form of dry eye tends to develop rapidly.15 The more severe ocular complications are associated with severe systemic cGVHD and poorer survival.2, 3 All patients enroled in this study had systemic signs of cGVHD at the time of admission. Two male patients, aged 18 and 51 years, died after 8 and 46 months of follow-up (due to heart attack and arterial embolism, respectively).

Some minor subclinical conjunctival changes are more likely to be due to the primary disease or the transplant conditioning regimen,16 whereas the more expressed abnormalities are considered to be a combined result of drug toxicity and GVHD.4 The histopathologic features of the lacrimal gland in dry eye as part of cGVHD include fibrosis of interstitium, increased number of CD34(+) stromal fibroblasts attached to various inflammatory cells, and excessive production of extracellular matrix components.17

All allogeneic BMT recipients, especially when treated for severe cGVHD, require close ophthalmic monitoring to keep early-stage complications such as keratoconjunctivitis sicca under control, as late complications are often severe and refractory to medical management. Although the efficacy of punctal occlusion in therapy of dry eye is well established,18 its use is not widespread. In this study, punctal occlusion was not performed in any patient before admission to the ophthalmology department, despite frequent lubrication. In all cases, we occluded the lacrimal puncta only during surgery.

The most common postoperative complication was PED. Many studies have established that corneal sensation is important for supplying neuropeptides, such as substance P, which functions as a growth factor to the corneal epithelium. Because all patients had severe dry eye with established subnormal preoperative corneal sensitivity, we assumed that their PED was mainly neurotrophic; and in one patient, the PED might also have been due to corneal epithelial stem cell deficiency. Tsubota et al19, 20 reported the efficacy of autologous serum application for the treatment of PED, where the probable mechanism is the acceleration of corneal epithelial cell migration and upregulation of mucin expression in the corneal epithelium. The essential tear components such as epidermal growth factor, transforming growth factor β, vitamin A, and substance P are necessary for corneal wound healing, therefore frequent application of autologous serum drops for such patients is important. Recently reported outcomes of umbilical cord serum application in dry-eye treatment also appear to be very promising for improving postsurgical corneal epithelial healing.21 Because of the high risk of primary disease recurrence in melting corneas, interrupted sutures seem to work better than running sutures. In two cases in our study in which running sutures were used during PK, suture loosening that occurred in the early postoperative period required partial suture removal to prevent wound dehiscence.

Lavid et al22 reported two cases of rare pathology, calcareous corneal degeneration (calcium deposits involving the full corneal thickness) in severe dry eye: one case secondary to GVHD and the other secondary to rheumatoid arthritis. Schlotzer-Schrehardt et al23 reported a similar case of calcareous degeneration of the corneal stroma after topical steroid-phosphate therapy for chronic keratoconjunctivitis after Stevens–Johnson syndrome. In our series, histologic examination of the removed tissue confirmed the preoperative diagnosis of calcareous degeneration in two corneas. Also, one transplanted cornea showed evidence of such a degeneration 2 months after PK. In this case of preoperative and postoperative calcareous degeneration in the same eye, Schirmer I and II scores were extremely low (2 and 0).

BMT recipients with GVHD are a very special group of patients owing to the minimal risk of corneal graft rejection as all of them receive systemic immunosuppressive therapy. On the other hand, when compared to non-immunosuppressed patients, BMT patients with GVHD had a much greater risk of infection (including eye infections) resulting from severe immune dysfunction. The addition of systemic antibiotics in the early postoperative period effectively prevented the more highly probable postsurgical eye infections.

Ambulatory visual acuity, according to Solomon et al14 was achieved in nine patients. Although the best postoperative visual acuity did not exceed 20/50, most of the patients gained useful near vision. The respectively poorer far vision often was due to coexisting cataract and astigmatism resulting from the difficulty of donor bed trephination in urgent keratoplasty (perforation). The irregularity and asymmetry of the corneal surface in patients with dry eye resulting from abnormalities in tear film thickness and smoothness despite aggressive lubrication with tear substitutes is another factor that disturbs the optical system, and therefore reduces postoperative visual acuity.24

The transparent or almost entirely transparent corneas in 82% of the eyes was better score than the reported outcomes of urgent keratoplasty or keratoplasty performed in dry eye.25, 26 Deterioration is expected to occur over time, however, because in severe dry eye, despite maximal management with tears, the prognosis for graft survival is not good. The poor prognosis also results from a lack of nutritional and growth factors contained in normal tears that are essential for proper limbal stem cell function. The likelihood of maintaining a transparent cornea with healthy epithelium over a long period is not good, but for these patients even several months of useful vision (in a few of them it has been 2–5 years) is invaluable for psychologic reasons.

One patient, an 18-year-old male who had undergone bilateral keratoplasty with a 1-week interval for large bilateral corneal perforations occurring rapidly 6 months after BMT, died due to arterial embolism 9 months after surgery. A month earlier, after the 8-month follow-up examination, his graft was bilaterally transparent and visual acuity improved equally in both eyes from 0.002 to 0.1. This case was very severe and the rapidly developing corneal perforations confirmed previous observations that more severe ocular complications are associated with poorer patient survival.2, 3, 27

Conclusions

Corneal grafting was an effective treatment for restoring corneal clarity and improving visual function in this series of patients. Multiple factors such as predilection for systemic and ocular infection, systemic drug toxicity, but primarily tear film deficiency, contribute to a decreased success ratio. Although the complication ratio was high and some patients might require regrafting, further treatment resulted in clinical improvement in the majority of patients.

References

Wingard JR, Piantadosi S, Vogelsang GB, Farmer ER, Jabs DA, Levin LS et al. Predictors of death from chronic graft-versus-host disease after bone marrow transplantation. Blood 1989; 74(4): 1428–1435.

Kiang E, Tesavibul N, Yee R, Kellaway J, Przepiorka D . The use of topical cyclosporin A in ocular graft-versus-host-disease. Bone Marrow Transplant 1998; 22(2): 147–151.

Claes K, Kestelyn P . Ocular manifestations of graft versus host disease following bone marrow transplantation. Bull Soc Belge Ophtalmol 2000; 277: 21–26.

Mencucci R, Rossi Ferrini C, Bosi A, Volpe R, Guidi S, Salvi G . Ophthalmological aspects in allogeneic bone marrow transplantation: Sjogren-like syndrome in graft-versus-host disease. Eur J Ophthalmol 1997; 7(1): 13–18.

Calissendorff B, el Azazi M, Lonnqvist B . Dry eye syndrome in long-term follow-up of bone marrow transplanted patients. Bone Marrow Transplant 1989; 4(6): 675–678.

Bray LC, Carey PJ, Proctor SJ, Evans RG, Hamilton PJ . Ocular complications of bone marrow transplantation. Br J Ophthalmol 1991; 75(10): 611–614.

Arocker-Mettinger E, Skorpik F, Grabner G, Hinterberger W, Gadner H . Manifestations of graft-versus-host disease following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Eur J Ophthalmol 1991; 1(1): 28–32.

Tsubota K, Kaido M, Moden YU, Satake Y, Bissen-Mijajima H, Schimazaki JH . A new surgical technique for deep lamellar keratoplasty with single running suture adjustment. Am J Ophthalmol 1998; 126(1): 1–8.

Wylegala E, Tarnawska D, Dobrowolski D . Deep lamellar keratoplasty for various corneal lesions. Eur J Ophthalmol 2004; 14: 467–472.

Ogawa Y, Okamoto S, Mori T, Yamada M, Mashima Y, Watanabe R et al. Autologous serum eye drops for the treatment of severe dry eye in patients with chronic graft-versus-host disease. Bone Marrow Transplant 2003; 31(7): 579–583.

Rocha EM, Pelegrino FS, de Paiva CS, Vigorito AC, de Souza CA . GVHD dry eyes treated with autologous serum tears. Bone Marrow Transplant 2000; 25(10): 1101–1103.

Faulkner WJ, Varley GA . Corneal diagnostic techniques. In: Krachmer JH, Mannis MJ, Holland EJ (eds). Cornea. Fundamentals of Cornea and External Disease, Vol. 1. Mosby:Philadelphia, 1996 pp 275–281.

Balaram M, Dana MR . Phacoemulsification in patients after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Ophthalmology 2001; 108(9): 1682–1687.

Solomon A, Ellies P, Anderson DF, Touhami A, Grueterich M, Espana EM et al. Long-term outcome of keratolimbal allograft with or without penetrating keratoplasty for total limbal stem cell deficiency. Ophthalmology 2002; 109(6): 1159–1166.

Ogawa Y, Okamoto S, Wakui M, Watanabe R, Yamada M, Yoshino M et al. Dry eye after haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Br J Ophthalmol 1999; 83(10): 1125–1130.

West RH, Szer J, Pedersen JS . Ocular surface and lacrimal disturbances in chronic graft-versus-host disease: the role of conjunctival biopsy. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol 1991; 19(3): 187–191.

Ogawa Y, Yamazaki K, Kuwana M, Mashima Y, Nakamura Y, Ishida S et al. A significant role of stromal fibroblasts in rapidly progressive dry eye in patients with chronic GVHD. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2001; 42(1): 111–119.

Kaido M, Goto E, Dogru M, Tsubota K . Punctal occlusion in the management of chronic Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Ophthalmology 2004; 111(5): 895–900.

Tsubota K, Goto E, Shimmura S, Shimazaki J . Treatment of persistent corneal epithelial defect by autologous serum application. Ophthalmology 1999; 106(10): 1984–1989.

Tsubota K . Tear dynamics and dry eye. Prog Retin Eye Res 1998; 17(4): 565–596.

Vajpayee RB, Mukerji N, Tandon R, Sharma N, Pandey RM, Biswas NR et al. Evaluation of umbilical cord serum therapy for persistent corneal epithelial defects. Br J Ophthalmol 2003; 87(11): 1312–1316.

Lavid FJ, Herreras JM, Calonge M, Saornil MA, Aguirre C . Calcareous corneal degeneration: report of two cases. Cornea 1995; 14(1): 97–102.

Schlotzer-Schrehardt U, Zagorski Z, Holbach LM, Hofmann-Rummelt C, Naumann GO . Corneal stromal calcification after topical steroid-phosphate therapy. Arch Ophthalmol 1999; 117(10): 1414–1418.

Dursun D, Monroy D, Knighton R, Tervo T, Vesaluoma M, Carraway K et al. The effects of experimental tear film removal on corneal surface regularity and barrier function. Ophthalmology 2000; 107(9): 1754–1760.

Claerhout I, Beele H, Van den Abeele K, Kestelyn P . Therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty: clinical outcome and evolution of endothelial cell density. Cornea 2002; 21(7): 637–642.

Pleyer U, Bertelmann E, Rieck P, Hartmann C . Outcome of penetrating keratoplasty in rheumatoid arthritis. Ophthalmologica 2002; 216(4): 249–255.

Jabs DA, Wingard J, Green WR, Farmer ER, Vogelsang G, Saral R . The eye in bone marrow transplantation. III. Conjunctival graft-vs-host disease. Arch Ophthalmol 1989; 107(9): 1343–1348.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tarnawska, D., Wylęgała, E. Corneal grafting and aggressive medication for corneal defects in graft-versus-host disease following bone marrow transplantation. Eye 21, 1493–1500 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702589

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702589

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Okuläre Graft-versus-Host-Disease

Der Ophthalmologe (2015)