Abstract

Purpose

Current indications for orbital surgery primarily aimed at improving cosmesis are considered in the context of subspecialist orbital practice by an ophthalmologist.

Scope

Thyroid eye disease, orbital vascular anomalies, and dermolipomas are common orbital diseases in which the symptoms can be purely cosmetic. Accurate anatomical awareness, preoperative scanning, control of medical factors including smoking and thyroid status, and endoscopic techniques have all contributed to the aesthetic outcome of orbital surgery. The threshold for performing reconstructive orbital surgery has also been lowered by public demand.

Conclusions

Orbital surgeons can therefore offer the familiar techniques, such as orbital decompression, for pure cosmesis. Sensitive history taking and awareness of the psychological element are of paramount importance for the orbital surgeon who develops a cosmetic practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The concept of cosmesis is intrinsic to all oculoplastic surgery. The word derives from the Greek ‘kosmeticos’, from kosmos, which means, ‘order or adornment’ and is defined in the Oxford English Dictionary1as an adjective, (i) ‘relating to treatment intended to improve a person's appearance’ or (ii)‘improving only the appearance of something’. It is the subtle difference between these two definitions that mirrors the terms, ‘reconstructive surgery’, which could be applied to the first definition, and ‘cosmetic surgery’, which applies to the second. There is a further word that introduces another element beyond restoration or improved appearance. ‘Aesthetic’, derived from ‘ aesthethai’ (perceive) in Greek, may be defined as, ‘concerned with beauty or the appreciation of beauty’ or ‘of pleasing appearance’.1 In the field of orbital surgery, pure aesthetic practice, that is, surgery to create beauty, is not yet an issue!

In its broadest sense, cosmetic orbital surgery encompasses craniofacial reconstruction and eyelid and periocular procedures, but this article only addresses the operations that are specifically performed on the orbit in oculoplastic practice. Any oculoplastic surgery carries risks associated with anaesthesia, bleeding, and infection, but orbital surgery incurs additional sight or life-threatening risks compared with preseptal procedures:

-

1

Optic nerve damage with visual impairment.

-

2

Impaired ocular motility causing diplopia.

-

3

CSF leak, possibly leading to meningitis.

However, in skilled hands, the risk of optic nerve damage and CSF leak is very small.

Orbital surgery therefore demands a scientific approach: methodical justification for surgery, recognition, and stabilization of medical conditions such as thyroid dysfunction, hypotensive anaesthesia, precise anatomical dissection based on preoperative imaging of bone and soft tissue, and meticulous haemostasis. The surgeon's choice of approach and preoperative technique is governed by training, continuing education, and experience.

Reconstructive surgery is performed to correct congenital or acquired defects, which adversely affect ocular function and/or social interaction. Cosmetic surgery aims at improving a normal appearance. Although the orbital surgeon's work is predominantly reconstructive, the skills gained and used in reconstructive surgery are also preparation for cosmetic orbital surgery. The decision to offer the latter is based on the surgeon's confidence in his/her results and motivation to perform such surgery. The patient's psyche dominates his/her own motivation to have surgery and their response to surgical outcome.2 The surgeon needs particular skill as a historian to ensure that the patient's story is elicited and documented accurately. Once a decision to offer surgery is made, the aims, limitations, and complications need to clear and confirmed in writing.3, 4

Facial disfigurement caused by orbital surgery has become less evident over the last 20 years. Earlier recognition and treatment of orbital tumours and increased use of chemotherapy rather than radiotherapy for tumours such as retinoblastoma and lymphoma has reduced the incidence of widespread tissue loss and ischaemic sequelae.5 An inconspicuous extended upper lid skin crease incision has replaced the Stallard–Wright lateral orbitotomy incision,6 which was positioned along the lateral orbital rim and zygoma, and often remained visible for months postoperatively. In many cases, it has also replaced the coronal incision.7 Although this incision behind the hair line remains a useful approach for extended access to the orbital roof and lateral orbital wall, it can be associated with loss of hair8 and scalp hypoaesthesia. Both of these approaches may be complicated by temporalis wasting.9 This can be minimised by avoiding damage to the superficial temporal artery, dissection in facial planes, and even repositioning of the muscle by fixation just inferior to the superotemporal ridge.10 The transconjunctival approach to floor fracture repair and orbital decompression has improved direct access to the orbital floor with reduced cutaneous scarring.11

Tailored exenteration with lid-sparing surgery,12 where possible, and the use of skin/muscle flaps,13 split skin grafts, and osseointegrated orbital implants14 have improved cosmetic outcomes, although most patients still prefer a patch!15

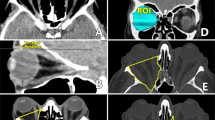

Thyroid eye disease involves an inflammatory response with deposition of GAG in the orbit causing orbital congestion and proptosis.16 The activity can be assessed using an activity score and MRI.17 Prevention of severe orbital involvement in thyroid eye disease by early disease recognition, achieving and maintaining euthyroid status,18, 19 avoiding cigarette smoke, and immunosuppression,20 when appropriate, is essential in preventing the need for surgery. There is no evidence that steroids reduce proptosis and it is possible that steroid-induced lipid deposition involves the orbit and may increase proptosis.21 Smoking adversely affects surgical outcomes as well as disease activity.22

Orbital decompression is justifiable when sight is threatened, despite the risk of complications: diplopia, infraorbital anaesthesia, upper lid retraction, sinusitis, orbital cellulitis, visual loss, globe malposition, lateral canthal deformity, blood loss, CSF leak, and meningitis. It is advisable in active disease in which dysthyroid optic neuropathy is not resolved using medical treatment.23 It is also an accepted management for inactive disease where proptosis is causing corneal exposure and photophobia owing to loss of brow shadow, chronic aching pain, or subluxation of the globe. Proptosis of more than 25 mm measured with the Hertel exophthalmometer almost invariably causes more than one of these symptoms. The position of the lower lid in relation to the inferior corneal limbus is a good guide to exposure caused by proptosis. If there is inferior scleral show, it is likely that orbital decompression will be required. Lower lid grafts only have limited success in addressing this type of exposure. Upper lid retraction is caused by proptosis, sympathetic stimulation, fibrosis of upper lid tissues, and inferior rectus fibrosis.24 In the absence of inferior rectus fibrosis and inferior scleral show, it is reasonable to treat this with upper lid recession, provided that the patient is euthyroid.

In practice, few individuals with cosmetic affects of TED are devoid of ocular symptoms. Quality of life is adversely affected by thyroid eye disease. The GO-QOL assessment25 includes eight questions referring to limitations of psychosocial function as a consequence of changed appearance. These include feeling socially isolated and experiencing adverse effects on self-confidence. Society can afford to value quality of life as well as working to lower morbidity and mortality. Cosmetic orbital surgery is justified for those who have comfortable protuberant eyes, which are sufficiently distressing to affect social interaction.26

In decompression for thyroid eye disease, endo-nasal and transconjunctival approaches avoid cutaneous scars. In addition, the ‘swinging eyelid’ approach allows decompression of the lateral wall to be performed from the internal aspect, usually utilising a drill.11 Removal of fibres of temporalis muscle is restricted to the area immediately over the osteotomy and wasting is not a problem (personal observation). Removal of the medial and lateral orbital walls and some orbital fat minimises the risk of diplopia.27 However, this symptom is always a possible complication and needs to be carefully explained to any patient undergoing decompression surgery and is particularly important in a cosmetic procedure.

Orbital decompression per se will not address the thickening of tissues elsewhere on the face, including the glabellar region, and patients need to be aware of this.

Enophthalmos may present with cosmetic symptoms following trauma28 or orbital decompression surgery.29 The risk of visual loss and diplopia must be clearly explained. Some patients are sufficiently motivated by altered body image and are prepared to undertake surgery despite discouragement and an explanation of these complications. Transplantation of fat into the orbit is an alternative to reconstruction of the orbital walls.30

Dermolipoma is a solid choristoma, which commonly presents as a lateral canthal mass,31 but can be irritable because of exposure or hairs on the surface. Once the nature of the lesion and the potential inflammatory complications of surgery are explained, most individuals will accept that intervention is unwise. If surgery is performed, one should remove the smallest amount that debulks the tumour.31, 32

Orbital vascular abnormalities may cause pain but frequently present with cosmetic symptoms.33, 34 They are notoriously difficult to remove and are best operated on in specialist centres. Effective surgery depends on all the measures already discussed to make surgery more safe, and may be assisted by embolisation.35 Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is an inherited systemic disease with eye involvement. Plexiform neurofibromas involving the orbit are not encapsulated and may be associated with facial homolateral hypertrophy.36 Cosmetic improvement can be achieved,37 although recurrence is extremely likely.

The concept of facial disfigurement in thyroid eye disease does not appear to be in the eye of the beholder.38 The surgeon should therefore be able to judge whether the patient's request is genuine, taking psychosocial factors into account. Assessment of these factors can be formalised using scales such as the GO-QOL25 and the Derriford Appearance Scale.39 Three-dimensional imaging and analysis offers new potential for analysing change after surgery.40 Orbital anomalies usually affect function as well as cosmesis and dysfunction is usually the prime indication for surgery. In a few cases where the appearance is the only issue, there is potential for the experienced orbital surgeon to apply his skills to cosmetic orbital surgery. In these cases, market forces will steer the future.41

References

Soanes C, Hawker S . Compact Oxford English Dictionary of Current English, 3rd ed. Oxford University Press: Corby, 2005.

Meningaud JP, Benadiba L, Servant JM, Herve C, Bertrand JC, Pelicier YJ . Depression, anxiety and quality of life: outcome 9 months after facial cosmetic surgery. Craniomaxillofac Surg 2003; 31 (1): 46–50.

Powell D, Hobgood T . Detection and management of the unstable patient. Facial Plast Surg N Am 2005; 13 (1): 169–180.

Makdessian AS, Ellis DA, Irish JC . Informed consent in facial plastic surgery: effectiveness of a simple educational intervention. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2004; 6 (1): 26–30.

Messmer EP, Fritz H, Mohr C, Heinrich T, Sauerwein W, Havers W et al. Long-term treatment effects in patients with bilateral retinoblastoma: ocular and mid-facial findings. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 1991; 229 (4): 309–314.

Wright JE . Surgery on the orbit. In: Symon L (ed). Neurosurgery, 3rd ed. Butterworth: London, 1979, pp 430–437.

Stewart WB, Levin PS, Toth BA . Orbital surgery: the technique of coronal scalp flap approach to lateral orbitotomy. Arch Ophthalmol 1988; 106: 1724–1726.

Fox AJ, Tatum SA . The coronal incision: sinusoidal, sawtooth and postauricular techniques. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2003; 5 (3): 259–262.

Kadri PA, Al-Mefty O . The anatomical basis for surgical preservation of temporal muscle. J Neurosurg 2004; 100 (3): 517–522.

Webster K, Dover MS, Bently RP . Anchoring the detached temporalis muscle in craniofacial surgery. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 1999; 27 (4): 211–213.

Paridaens DA, Verhoeff K, Bouwens D, van den Bosch WA . Transconjunctival orbital decompression in Graves’ ophthalmopathy: lateral approach ab interno. Br J Ophthalmol 2000; 84 (7): 775–781.

Shields JA, Shields CL, Demirici H, Honavar SG, Singh AD . Experience with eyelid-sparing orbital exenteration: the 2000 Tullos O Coston Lecture. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2001; 17 (5): 335–361.

Chepedha DB, Wang SJ, Marentette LJ, Bradford CR, Boyd CM, Prince ME et al. Restoration of the orbital aesthetic subunit in complex midface defects. Larngoscope 2004; 114 (10): 1706–1713.

Nerad JA, Carter KD, La Velle WE, Fyler A, Branemark PI . The osseointegration technique for the rehabilitation of the exenterated orbit. Arch Ophthalmol 1991; 109 (7): 1032–1038.

Ben Simon GJ, Schwarcz RM, Douglas R, Fiaschetti D, McCann JD, Goldberg RA . Orbital exenteration: one size does not fit all. Am J Ophthalmol 2005; 139 (1): 152–153.

Boulos PR, Hardy I . Thyroid-associated orbitopathy: a clinicopathalogic and therapeutic review. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2004; 15: 389–400.

Mayer EJ, Fox DL, Herdman G, Hsuan J, Kabala J, Goddard P et al. Signal intensity, clinical activity and cross-sectional area on MRI scans in thyroid eye disease. Eur J Radiol (E-pub ahead of print).

Tallstedt L, Lundell G, Blomgren H, Blom J . Does early administration of thyroxine reduce the development of Graves’ ophthalmopathy after radioiodine treatment?. Eur J Endocrinol 130 (5): 494–497.

Wiersinga W, Bartelena L . Epidemiology and prevention of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Thyroid 2002; 12 (10): 855–860.

Marcocci C . Current medical management of thyroid orbitopathy in orbital disease: present status and future challenges. In: J Rootman (ed). Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton FL, 2005.

Patel NG, Holder JC, Smith SA, Kumar S, Eggo MC . Differential regulation of lipogenesis and leptin production by independent signalling pathways and rosglitazone during human adipocyte differentiation. Diabetes 2003; 52 (1): 43–50.

Krueger JK, Rohrich RJ . Clearing the smoke: the scientific rationale for tobacco abstention with plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001; 108 (4): 1063–1073.

Wakelkamp IM, Baldeschi L, Saeed P, Mourits MP, Prummel MF, Wiersinga WM . Surgical or medical decompression as a first-line treatment of optic neuropathy in Graves’ ophthalmopathy? A randomized controlled trial. Clin Endocrinol (Oxford) 2005; 63 (3): 323–328.

Thaller VT, Kaden K, Lane CM, Collin JR . Thyroid lid surgery. Eye 1987; 1 (5): 609–614.

Wiersinga WM, Prummel MF, Terwee CB . Effects of Graves’ ophthalmopathy on quality of life. J Endocrinol Invest 2004; 27 (3): 259–264.

Lyons CJ, Rootman J . Orbital decompression for disfiguring exophthalmos in thyroid orbitopathy. Ophthalmology 1994; 101 (2): 223–230.

Graham SM, Brown CL, Carter KD, Song A, Nerad JA . Medial and lateral orbital wall surgery for balanced decompression in thyroid eye disease. Laryngoscope 2003; 113 (7): 1206–1209.

Grant MP, Iliff NT, Manson PN . Strategies for the treatment of enophthalmos. Clin Plast Surg 1997; 24 (3): 539–550.

Rose GE, Lund VJ . Clinical features and treatment of late enophthalmos after orbital decompression: a condition suggesting cause for idiopathic ‘imploding antrum’ (silent sinus) syndrome. Ophthalmology 2003; 110 (4): 819–826.

Rose GE, Collin R . Dermofat grafts to the extraconal orbital space. Br J Ophthalmol 1992; 76 (7): 408–411.

McNab AA, Wright JE, Caswell AG . Clinical features and surgical management of dermolipomas. Aust NZ J Ophthalmol 1990; 18 (2): 159–162.

Beard C . Dermolipoma surgery, or, ‘an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure’. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 1990; 6 (3): 153–157.

McNab A . Orbital vascular anatomy and vascular lesions. Orbit 2003; 22 (2): 7–9.

Rootman J . Vascular malformations of the orbit: hemodynamic concepts. Orbit 2003; 22 (2): 103–120.

Lacey B, Rootman J, Marotta TR . Distensible venous malformations of the orbit: clinical and hemodynamic features and a new technique of management. Ophthalmology 1999; 106 (6): 1197–1209.

Polito E, Leccisotti A, Frezzotti R . Cosmetic possibilities and problems in eyelid neurofibromas. Ophthalmic Paediatr Genet 1993; 14 (1): 43–50.

Lee V, Ragge NK, Collin JR . Orbitotemporal neurofibromatosis: clinical features and surgical management. Ophthalmology 2004; 111 (2): 382–388.

Terwee CB, Dekker FW, Bonsel GJ, Heisterkamp SH, Prummel MF, Baldeshi L et al. Facial disfigurement: is it in the eye of the beholder? A study in patients with Grave's ophthalmopathy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxford) 2003; 58 (2): 192–198.

Harris DL, Carr AT . The Derriford appearance scale (DAS59): a new psychometric scale for the evaluation of patients with disfigurements and aesthetic problems of appearance. Br J Plast Surg 2001; 54 (3): 216–222.

Honrado CP, Larrabee Jr WF . Update in three-dimensional imaging in facial plastic surgery. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004; 12 (4): 327–331.

Alsarraf R, Alsarraf NW, Larrabee Jr WF, Johnson Jr CM . Cosmetic surgery procedures as luxury goods: measuring price and demand in facial plastic surgery. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2002; 4 (2): 105–110.