Abstract

Purpose

To determine whether topical ketorolac (Acular) is more effective than artificial tears in treating the signs and symptoms of idiopathic episcleritis.

Methods

In this prospective, randomised, double-blind study, 38 eyes of 37 patients presenting with idiopathic episcleritis were allocated to receive either topical ketorolac (0.5%) or artificial tears three times a day for 3 weeks. The severity of patients’ signs (episcleral injection and the number of clock hours affected) were recorded at weekly intervals. Patients' symptoms (perceived redness and pain scores) were recorded using a daily diary.

Results

There was no significant difference in the ophthalmic signs between the two groups at each assessment, including intensity of episcleral injection and the number of clock hours affected. No significant difference was found in the time to halve the baseline redness intensity scores (4.4 vs 6.1 days, P=0.2) or pain scores (3.6 vs 4.3 days, P=0.55). Significantly more patients on ketorolac reported stinging at the first follow-up visit (P<0.001).

Conclusion

Topical ketorolac is not significantly better than artificial tears in treating the signs or symptoms of idiopathic episcleritis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Episcleritis is an inflammation of the loose, highly vascular connective tissue lying deep to Tenon's capsule and superficial to the sclera. The condition is usually idiopathic but may be associated with serious underlying ophthalmic and systemic disorders such as ocular rosacea, keratoconjunctivitis sicca, atopy, systemic vasculitis, and inflammatory bowel disease.1

Usually a self-limiting condition, episcleritis typically lasts approximately for 21 days.2 Patients may request treatment because of discomfort or redness, and a number of options have been shown to speed recovery. These include topical steroids2, 3, 4 and systemic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as flurbiprofen3, 5 and oxyphenbutazone.6 However, these therapies are associated with potentially harmful side effects.

A number of topical NSAIDs have become available in recent years, offering the potential to reduce these side effects significantly. While these drugs have been shown to be safe and effective in the treatment of postcataract surgery inflammation7, 8 and seasonal allergic conjunctivitis,9, 10 studies into their use for treating episcleritis have shown mixed results. Beneficial effects were demonstrated for topical oxyphenbutazone2 and 2-(2-hydroxy-4-methylphenyl) aminothiazole hydrochloride,11 although neither is available commercially, while topical flurbiprofen is no better than placebo.3

As a result of the conflicting data on the efficacy of topical NSAIDs, we conducted a randomised, double-blind trial of topical ketorolac (Acular) vs placebo for the treatment of episcleritis.

Methods

In this prospective study, patients presenting to one eye casualty department diagnosed with either nodular or diffuse episcleritis were recruited to take part. The study received approval from the local Research and Ethics committee and all patients gave written informed consent before participation.

A detailed history was taken with particular emphasis on previous episodes of episcleritis, history of atopy, bowel disturbance, or joint problems. Each patient received a thorough anterior and posterior segment examination and the intraocular pressure was measured before recruitment. Patients with the typical clinical profile of episcleritis were recruited; episcleral injection with or without overlying conjunctival injection and with or without nodule formation. No patient with scleral involvement was recruited. Patients were excluded if other ocular pathology or systemic disease existed or there was a contraindication to receiving NSAIDs. It was not considered necessary to perform further systemic investigations in the recruited patients.

The severity of the patients’ signs was graded by assessing both the intensity and area of episcleral injection. Intensity was graded on a scale of 0–4 using a system similar to that previously described2 (0=no injection, 1= very mild, 2=mild, 3=moderate, and 4=severe). The area of injection was measured as the number of clock hours affected. In addition, patients were given a diary sheet to record their daily pain and redness scores on a visual analogue scale for the duration of treatment (0 = no pain or redness, 10= severe pain or redness).

Each patient was randomly allocated to receive either topical ketorolac trometamol 0.5% (Acular; Allergan, High Wycombe, Bucks, UK) or Liquifilm tears (Allergan) three times a day for 3 weeks. The bottles used in the study had their original labels removed and were labelled with a unique identifying code. A nurse not involved in the study selected a sealed envelope containing a prewritten card and dispensed the appropriate bottle according to the card instructions. Both patients and observers were therefore masked to the treatment group allocated to the patient.

Patients were reviewed at weekly intervals for 3 weeks and their visual acuity, intensity of redness, number of clock hours affected, intraocular pressure, and the state of the corneal epithelium recorded. At each visit, the signs were graded as detailed above by an observer masked to the patient's treatment group. Enquiry was made into treatment-related side effects. Treatment was continued for the full 3 weeks unless the patient requested otherwise or their condition deteriorated significantly requiring a change in treatment, or it had resolved. Those patients whose episcleritis resolved were subsequently graded ‘zero’ for signs and symptoms for the purpose of statistical evaluation.

The Mann–Whitney test was used to compare the two treatment groups’ data with respect to the grading scores for signs (eg redness intensity, clock hours). An unpaired Student's t-test was used to compare the time to half baseline diary scores for redness and discomfort for the two groups. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. A 2-day reduction in the time to half baseline symptom scores was considered a clinically relevant result. Using these criteria and data from previous studies regarding the natural history of episcleritis,2, 11 a power calculation revealed that 15 subjects per group would give an 80% chance of detecting a significant difference.

Results

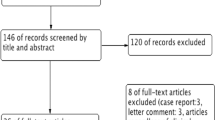

In all, 38 eyes of 37 patients were recruited into the study. This sample included one patient who represented with episcleritis in the fellow eye some months after the first and was recruited a second time for the study. One patient failed to attend any further follow-up and was therefore excluded from the analysis. Thus, 19 eyes received ketorolac and 18 Liquifilm tears. The mean age of the patients was 48.4 years (range 27–73) in the ketorolac group and 45.9 (21–69) in the controls (P=0.62, t-test). There were nine males in the ketorolac group and 12 in the control group. There was no statistical difference between the two groups for visual acuity (P=0.41) or intraocular pressure (P=0.34).

Regarding patient signs, Table 1 shows the redness intensity gradings at each visit. At no time was there a statistical difference between the two groups. Table 2 shows a similar result for the number of clock hours affected at each visit. The change from baseline scores for both redness intensity and clock hours were also calculated for each visit. Again, there was no statistical difference between the treatment groups at any time.

Patient symptoms recorded as daily redness and pain scores in the diaries are illustrated in Figures 1 and 2 respectively. At no time was there a statistical difference between the two groups. The mean number of days to halve baseline redness score was 4.4 for ketorolac and 6.1 for artificial tears (P=0.2). Power calculation on this data confirmed the study had a power of 80% to detect a difference of 1.8 days. The mean number of days to halve the baseline pain scores were 3.6 and 4.3, respectively (P=0.55), the study having an 80% power to detect a difference of 1.9 days.

There was no significant difference between the two groups for mean intraocular pressure measurement at any time. Two patients from each group developed a few areas of punctate keratopathy, not deemed to be clinically significant. Of the patients receiving ketorolac, 63% reported stinging, compared to 5% of patients using artificial tears (P<0.001, Fisher's-exact). Two patients receiving artificial tears had to withdraw early (at days 7 and 11) due to worsening of symptoms. Both were treated with topical steroids and recovered. Their data were included in the statistical analysis up to the point of withdrawal from the study.

Discussion

Episcleritis is usually a benign, self-limiting condition associated with episcleral injection and discomfort. Most cases do not need treatment, although some patients may request or require medication, particularly if the disease is severe or becomes recurrent.

A number of studies have shown that topical steroids are effective in the treatment of episcleritis.2, 3, 4 Unfortunately, they are associated with potentially serious side effects, such as raised intraocular pressure, cataracts, and the possible reactivation of ocular herpetic disease. Oral NSAIDs are an alternative therapy.3, 5, 6 These are also effective, but again have a number of potentially serious side effects such as gastrointestinal irritation, peptic ulceration, and exacerbation of asthma. An ideal treatment for episcleritis would utilise the clinical effectiveness of oral NSAIDs, thereby avoiding steroids usage, but which could be locally applied to the site of disease to reduce systemic side effects. Topical NSAIDs may fit these criteria.

Topical NSAIDS have been widely used in the treatment of a number of anterior segment disorders. They are as effective as steroids in controlling mild-to-moderate inflammation after phacoemulcification cataract surgery7, 8 and are also useful in the maintenance of intraoperative mydriasis,12 treatment of corneal abrasions,13 pain relief after refractive surgery14 and the treatment of seasonal allergic conjunctivitis.9, 10

Previous studies into the use of topical NSAIDs for the treatment of episcleritis have produced conflicting results. A randomised study comparing topical flurbiprofen (0.03%) with placebo and topical steroids found no significant benefit for the NSAID compared to topical normal saline (0.5%), while confirming the benefit of steroid3. A double-blind study comparing topical oxyphenbutazone (10%) with topical steroid showed a similar level of effectiveness, both being significantly better than placebo.2 Our study failed to demonstrate a significant difference between topical ketorolac and placebo, despite being of sufficient power to detect a difference between the two groups of under two days for the halving of redness and pain scores.

Our placebo agent was Liquifilm tears, a proprietary ocular lubricant. Previous authors have not always specified the nature of their placebo2, 4 while others have used ‘normal saline’3 or ‘drug vehicle’.11 Although this agent itself might conceivably be effective in treating episcleritis, we know of no studies to support this and we therefore considered it a suitable choice of placebo. Apart from the active nonsteroidal ingredient, the two preparations have similar constituents including benzalkonium chloride preservative.

Ketorolac acts by inhibiting cyclo-oxygenase, essential for the biosynthesis of prostaglandins.15 As mentioned previously, it is effective in the treatment of a number of different inflammatory anterior segment conditions. It is therefore surprising that the topical preparation has no demonstrable effect on the signs or symptoms of episcleritis. While the underlying disease process of episcleritis is unknown, it is conceivable that it is not a prostaglandin-dependent process, hence the lack of effectiveness of topical ketorolac. However, oral NSAIDs are effective in treating episcleritis,5, 6 conflicting with this theory.

Ketorolac is known to penetrate the cornea well, with the epithelium acting as a reservoir to maintain aqueous levels with a half-life of 3.77 h in rabbits.16 Animal studies also show that topically instilled ketorolac leads to distribution of the drug throughout ocular tissues, including the conjunctiva and sclera.15 Therefore, nonpenetration of the conjunctiva and episclera by the drug would seem not to explain the lack of effect seen in our study.

It is generally accepted that topical application allows higher concentrations of the drug to be achieved locally. However, the minimum local concentration of ketorolac necessary to control episcleritis is unknown. It is feasible that a dose regimen of three times a day is insufficient. Several studies conducted outside the UK have used ketorolac at a frequency of four times a day for the treatment of postoperative inflammation7, 8 and cystoid macular oedema17 without significant side effects. Potential undesirable effects of more frequent dosing with topical NSAIDs may include corneal thinning and melting, particularly in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or dry eyes.

In conclusion, topical ketorolac given three times a day is not significantly better than artificial tears at treating the signs and symptoms of episcleritis. Further studies are needed to determine whether ketorolac is safe enough to allow dosage escalation in a manner similar to topical steroids for the treatment of episcleritis in patients without ocular comorbidity.

References

Akpek EK, Uy HS, Christen W, Gurdal C, Foster CS . Severity of episcleritis and systemic disease. Ophthalmology 1999; 106: 729–731.

Watson PG, McKay DAR, Clemett RS, Wilkinson P . Treatment of episcleritis. A double-blind trial comparing betamethasone 0.1 percent, oxyphenbutazone 10 per cent, and placebo eye ointments. Br J Ophthalmol 1973; 57: 866–870.

Lyons CJ, Hakin KN, Watson PG . Topical flurbiprofen: an effective treatment for episcleritis? Eye 1990; 4: 521–525.

Lloyd-Jones D, Tokarewicz, Watson PG . Clinical evaluation of clobetasone butyrate eye drops in episcleritis. Br J Ophthalmol 1981; 65: 641–643.

Watson PG . Diseases of the sclera and episclera. In: Duane TD (ed). Clinical Ophthalmology, Vol 4. Chapter 23, Harper and Row: Philadelphia, 1987.

Watson PG, Lobascher DJ, Sabiston DW, Lewis-Faning E, Fowler PD, Jones BR . Double-blind trial of the treatment of episcleritis—scleritis with oxyphenbutazone or prednisolone. Br J Ophthalmol 1966; 50: 463–481.

Heier J, Cheetham JK, Degryse R, Dirks MS, Caldwell DR, Silverstone DE et al. Ketorolac tromethamine 0.5% ophthalmic solution in the treatment of moderate to severe ocular inflammation after cataract surgery: a randomized, vehicl-controlled clinical trial. Am J Ophthalmol 1999; 127: 253–259.

El-Harazi SM, Ruiz RS, Feldman RM, Villanueva G, Chuang AZ . A randomized double-masked trial comparing ketorolac tromethamine 0.5%, diclofenac sodium 0.1%, and prednisolone acetate 1% in reducing post-phacoemulsification flare and cells. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers 1998; 29: 539–544.

Tinkleman DG, Rupp G, Kaufman H, Pugley J, Schultz N . Double-masked, paired-comparison clinical study of ketorolac tromethamine 0.5% ophthalmic solution compared with placebo eyedrops in the treatment of seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. Surv Ophthalmol 1993; 38 (Supp): 133–140.

Ballas Z, Blumenthal M, Tinkleman DG, Kriz R, Rupp G . Clinical evaluation of ketorolac tromethamine 0.5% ophthalmic solution for the treatment of seasonal allergic conjunctivitis. Surv Ophthalmol 1993; 38 (Supp): 141–148.

Liu CSC, Ramirez-Florez S, Watson PG . A randomised double blind trial comparing the treatment of episcleritis with topical 2-(2-hydroxy-4-methylphenyl) aminothiazole hydrochloride 0.1% (CBS 113A) and placebo. Eye 1991; 5: 678–685.

Solomon KD, Turkalj JW, Whiteside SB, Stewart JA, Apple DJ . Topical 0.5% ketorolac vs 0.03% flurbiprofen for inhibition of miosis during cataract surgery. Arch Ophthalmol 1997; 115: 1119–1122.

Kaiser PK, Pineda R . A study of topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drops and no pressure patching in the treatment of corneal abrasions. Ophthalmology 1997; 104: 1353–1359.

McDonald MB, Brint SF, Caplan DI, Bourque LB, Shoaf K . Comparison of ketorolac tromethamine, diclofenac sodium, and moist drops for ocular pain after radial keratotomy. J Cataract Refract Surg 1999; 25: 1097–1108.

Flach AJ . Cyclo-oxygenase inhibitors in ophthalmology. Surv Ophthalmol 1992; 36 (4): 259–284.

Summary of product characteristics. Allergan 2001.

Heier JS, Topping TM, Baumann W, Dirks MS, Chern S . Ketorolac versus prednisolone versus combination therapy in the treatment of acute pseudophakic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2000; 107 (11): 2034–2038.

Acknowledgements

We thank Allergan for supplying the treatment drops used in this study. In addition, we thank Alan Rotchford, Specialist Ophthalmic Registrar at Queens Medical Centre, Nottingham, for his helpful guidance on the statistical analysis of the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This study was presented as a poster at the Royal College of Ophthalmologists' Annual Congress in Birmingham, May 2003.

The authors have no proprietary interests in any of the treatments mentioned in this paper. Allergan kindly supplied the drops used in this study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Williams, C., Browning, A., Sleep, T. et al. A randomised, double-blind trial of topical ketorolac vs artificial tears for the treatment of episcleritis. Eye 19, 739–742 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6701632

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6701632

This article is cited by

-

Extraintestinal Manifestations of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Epidemiology, Etiopathogenesis, and Management

Current Gastroenterology Reports (2019)