Abstract

Purpose The Drusen Laser Study (DLS) of high-risk age-related maculopathy (ARM) is a randomised, controlled clinical trial designed to answer two questions: (1) Do drusen resolve after macular laser photocoagulation (2) Does macular laser photocoagulation prevent choroidal neovascularisation (CNV) in high-risk eyes? In this report, we present the results of the interim, pooled analysis of CNV prophylaxis for patients in the Unilateral Group of the DLS.

Methods The DLS is a randomised controlled clinical trial of prophylactic macular photocoagulation for high-risk ARM. Patients in the Unilateral Group had a neovascular complication in the first eye; their fellow eye (Study Eye) had visual acuity of 6/12 or better and drusen. Following informed consent, patients were randomised to the Treatment Group or the No Treatment Group. Patients randomised to treatment received 12 light spots of argon laser photocoagulation to their Study Eye: four burns were placed 750 μm from the centre of the fovea at 12, 3, 6, and 9 o'clock, and the eight remaining burns were placed 1500 μm from the centre of the fovea at 12, 1:30, 3, 4:30, 6, 7:30, 9, and 10:30 o'clock. Drusen were treated directly only if they were present at the protocol treatment locations. All patients were followed in an identical fashion at regular intervals. Best-corrected visual acuity was measured and recorded by a masked observer. Fluorescein angiography was performed at baseline and yearly review, as well as nonprotocol visits if symptoms suggested CNV. Five clinical centres utilised and conformed to a common DLS protocol. Patient care and data collection methodologies were deemed sufficiently similar to permit a pooled data analysis.

Results There were 156 patients included in the interim analysis, and timed information was available on 153. CNV occurred in 21 of 81 (26%) patients in the Treatment Group and in 13 of 75 (17%) patients in the No Treatment Group (P=0.19). Kaplan–Meier survival analysis showed earlier onset of CNV in the Treatment Group compared to patients in the No Treatment Group (statistical significance not calculated). Visual acuity loss at 2 years occurred in nine of 54 (17%) patients in the Treatment Group compared to the two of 48 (4%) patients in the No Treatment Group (P=0.056).

Conclusions We are only the second group to identify possible laser-induced CNV despite other similar studies in progress. Equipoise of the DLS investigators was lost, and recruitment was halted. We feel ethically bound to notify the ophthalmic community of this finding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

An effective treatment armamentarium for age-related maculopathy (ARM) would ideally include therapy to prevent choroidal neovascularisation (CNV) in eyes at risk for this complication. Blindness prevention would circumvent the psychological and financial burden on society from this disorder.

We have studied patients with ARM at high risk of CNV in our Drusen Laser Study (DLS) with particular interest in two clinical features: drusen disappearance and visual acuity loss consequent to the development of CNV. In accordance with our DLS Pilot Study experience, we predicted decreasing drusen size and number, or perhaps even disappearance of drusen following laser photocoagulation. More importantly, we hoped to provide long-term preservation of visual acuity by prevention of CNV. The randomised controlled design and execution of the DLS were necessary to identify any difference in treated eyes compared to eyes with similar characteristics randomised to observation.

This report presents the results of our interim, pooled analysis of patients in the Unilateral Group regarding incidence of CNV and visual acuity loss.

Materials and methods

The DLS is a randomised, controlled clinical trial of macular laser photocoagulation for high-risk ARM. The goals of the study were to assess drusen response following prophylactic macular laser photocoagulation and reduce the risk of visual acuity loss from neovascular complications. Initial clinical observations from the DLS at Moorfields have been reported previously.1

The following is a brief overview of eligibility criteria for patients in the Unilateral Group of the DLS:

Eligibility

-

1

Drusen with or without focal RPE hyperpigmentation in the Study Eye, and a neovascular lesion in the fellow eye (CNV, pigment epithelial detachment, tear of the RPE, or fibrovascular scar).

-

2

Best-corrected visual acuity of 6/12 or better in the Study Eye.

-

3

Age 50 years or older.

-

4

No other eye disease that might influence visual acuity.

-

5

Suitable for fundus photography.

-

6

Ability to provide informed consent.

-

7

Available for regular review.

Exclusion criteria

-

1

Geographic atrophy in either eye.

-

2

Allergy to fluorescein.

The complete protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics and Research Committees of the Moorfields Eye Hospital before patient recruitment was begun. Procedures for the use of human subjects in DLS research conformed to the doctrine of the Declaration of Helsinki.

All patients provided informed consent prior to baseline assessment. The baseline assessment included best-corrected visual acuity, slit-lamp biomicroscopy, fundus examination, and fundus fluorescein angiography. All eligible patients were randomised. The Study Eye was randomised to treatment or no treatment.

Study Eyes randomised to treatment received photocoagulation using an argon green or yellow dye laser with 200 μm spot size and 0.2 s duration. The lowest energy setting that produced a very faint burn was used (average settings 65–120 mW). In all, 12 total burns were given: four burns 750 μm from the centre of the fovea at 12, 3, 6, and 9 o'clock, and eight burns 1500 μm from the centre of the fovea at 12, 1 : 30, 3, 4 : 30, 6, 7 : 30, 9, and 10 : 30 o'clock. Drusen were treated directly only if they were coincident with protocol treatment locations. Immediate post-treatment colour photography was not performed as the laser burns were not visible at completion of treatment.

Routine review was performed at 3 months, 6 months, 1 year, 18 months, 2, and 3 years after randomisation. All patients were refracted, and best-corrected visual acuity was measured and recorded by a masked optometrist using the ETDRS chart. (Visual acuity data from the 3-month visit were not included in this analysis, as a protocol refraction was not performed.) Colour fundus photography was performed at each visit. Fundus fluorescein angiography was performed at annual review and additionally as clinically indicated. Interim patient evaluations were performed as dictated by symptoms.

An interim data analysis was performed to evaluate two outcomes comparing the Treatment Group to the No Treatment Group: the proportion of patients in each group who developed CNV during follow-up and visual acuity at 2 years. The proportion of patients in each group who developed CNV was compared using the χ2 test with a level of statistical significance of P≤0.001. A Kaplan–Meier survival plot was computed to evaluate the temporal relationship of the incidence of CNV. Visual acuity loss was defined as a worsening on the ETDRS chart of greater than or equal to 15 letters. Fisher's exact test was used to evaluate visual acuity with a level of statistical significance of P≤0.001.

Results

At the time of the interim analysis, there were 161 patients in the Unilateral Group of the DLS. Five of 161 patients were excluded from the analysis for the following reasons: two inappropriate randomisations, one incorrect diagnosis, and two lost to follow-up. (One sought treatment elsewhere; another was unable to return because of immobility.) Of the remaining 156, timed information was available on 153.

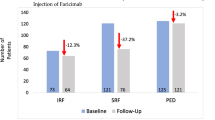

Table 1 shows the incidence of CNV in the Treatment Group compared to the No Treatment Group. CNV occurred in 21 of 81 (26%) patients in the Treatment Group and 13 of 75 (17%) patients in the No Treatment Group. The difference was not statistically significant (P=0.19). The age and sex of those who developed CNV did not differ significantly from those who did not develop CNV (data not shown). There was no evidence to suggest that the incidence of CNV differed between study centres (data not shown).

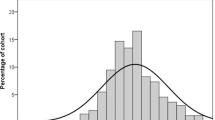

Figure 1 is a Kaplan–Meier survival plot that shows earlier onset of CNV in the Treatment Group compared to patients in the No Treatment Group (statistical significance was not calculated).

Kaplan–Meier survival plot. The horizontal axis represents time in months. The vertical axis represents the proportion of the original complete cohort without CNV. Each decrement from 1.00 represents one patient who developed CNV during review. Note an apparent earlier incidence of CNV in the Treatment Group compared to the No Treatment Group. Also note the apparent crossover at 38 months. There were insufficient timed data available for a reliable statistical analysis of any difference between these groups.

Table 2 shows the comparison of visual acuity loss in the Treatment Group to the No Treatment Group at 2 years. At 2 years, there were 102 observations available for analysis, or 63% of the entire cohort. Visual acuity loss occurred in 9 of 54 (17%) patients in the Treatment Group compared to the two of 48 (4%) patients in the No Treatment Group. This difference was not statistically significant.

Discussion

Our clinical and data acquisition methods were deemed to be sufficiently similar at each centre to allow pooling of data. The timing of the interim analysis coincided with the principal investigators' loss of equipoise. They became increasingly concerned about laser-induced CNV and were reluctant to continue new patient recruitment. The clinicians felt that their duty to patients was to stop the trial. Despite their concern, the results from this interim analysis did not provide sufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis.

A true difference between the Treatment and No Treatment groups may exist, but was not identified by this interim analysis. This may have been consequent to incomplete patient recruitment and the truncated review period. These weaknesses are inherent in pilot studies and the interim analysis process.2

Our procedural and ethical dilemmas were not dissimilar to those reported by the CNV Prevention Trial.3 Our Kaplan–Meier survival analysis suggested earlier onset of CNV in treated eyes compared to untreated eyes, although there was a suggestion of a crossover in survival curves with time. Calculation of statistical significance of the Kaplan–Meier survival plot was not appropriate for this interim analysis because of possible crossover and paucity of longer-term review data.

The principal investigators unanimously agreed to suspend new patient recruitment and to announce these results, even though ‘stop’ criteria were not reached. Despite several other similar studies in progress, we are only the second group to express concern regarding laser-induced CNV.4,5,6,7,8,9,10

A further report from the CNV Prevention Trial described a relation between higher-intensity laser treatment on earlier onset of CNV when compared to the low-intensity group.11 We were unable to perform a similar analysis for two reasons. Firstly, our pilot study experience showed that minimal laser intensity was sufficient to promote drusen resorption. Since gentle treatment produced no visible burns at the completion of treatment, post-treatment fundus photography was not required. We acknowledge that masked grading of immediate post-treatment photographs would substantiate our assertion that no laser burns were evident immediately post-treatment; however, we are unable to obtain these photographs in retrospect.

Evidence contained in this report supports the conclusion that prophylactic laser treatment of high-risk ‘unilateral ARM’ may only be justified within a randomised controlled clinical trial. We are aware that patients receive laser treatment outside controlled clinical trials, despite the lack of evidence of safety and efficacy. This report may prevent those patients from losing visual acuity as a consequence.

We do not believe that the information in this report can be extrapolated to patients with bilateral high-risk drusen. Prophylactic photocoagulation in patients with bilateral high-risk drusen may prove beneficial, before the unfavourable natural history of neovascular ARM has declared itself.

References

Owens SL, Guymer RH, Gross-Jendroska M, Bird AC . Fluorescein angiographic abnormalities after prophylactic macular photocoagulation for high-risk age-related maculopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 1999; 127: 681–687.

Ferris FL, Murphy RP . The peril of the pilot study. Arch Ophthalmol 1996; 114: 1506–1507.

The Choroidal Neovascularization Prevention Trial Research Group . Laser treatment in eyes with large drusen: short-term effects seen in a pilot randomized clinical trial. Ophthalmology 1998; 105: 11–23.

Wetzig PC . Photocoagulation of drusen-related macular degeneration: a long-term outcome. Tr Am Ophthal Soc 1994; 92: 299–306.

Sarks SH, Arnold JJ, Sarks JP, Gillies MC, Walter CJ . Prophylactic perifoveal laser treatment of soft drusen. Aus NZ J Ophthalmol 1996; 24: 15–26.

Olivestedt G, Algvere PV . Laser photocoagulation of soft drusen in ARM: a pilot study. Invest Ophthal Vis Sci 1996; S224.

Figueroa MS, Regueras A, Bertrand J, Aparicio MJ, Manrique MG . Laser photocoagulation for macular soft drusen updated results. Retina 1997; 17: 378–384.

Little HL, Showman JM, Brown BW . A pilot randomized controlled study on the effect of laser photocoagulation of confluent soft macular drusen. Ophthalmology 1997; 104: 623–631.

Frennesson C, Nilsson SEG . Prophylactic laser treatment in early age related maculopathy reduced the incidence of exudative complications. Br J Ophthalmol 1998; 82: 1169–1174.

Olk RJ, Friberg TR, Stickney KL, Akduman L, Wong KL, Chen MC et al. Therapeutic benefits of infrared (810-nm) diode laser macular grid photocoagulation in prophylactic treatment of nonexudative age-related macular degeneration: two year results of a randomized pilot study. Ophthalmology 1999; 106: 2082–2090.

Kaiser RS, Berger JW, Maguire MG, Ho A, Javornik NB, and the Choroidal Neovascularization Prevention Trial Study Group. Laser burn intensity and the risk for choroidal neovascularization in the CNVPT fellow eye study. Arch Ophthalmol 2001; 119: 826–832.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Members of the Drusen Laser Study Group and their affiliations are listed in the Appendix.

Proprietary interests/funding: None

Appendix : Drusen Laser Study Group

Appendix : Drusen Laser Study Group

Freie Universität Berlin, Universitätsklinikum Benjamin Franklin, Berlin, Germany

Investigators: Mirjam Gross (Principal Investigator), Simone Potthöfer, Tim Behme, Michael Föerster.

Medical photographer: Gesa Bröeskamp.

Ruprecht Karls Universität Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany

Investigators: Frank G Holz (Principal Investigator), Caren Bellmann, Charlotte Poloschek, Florian Schütt, Stephanie Staudt, Donate Taufonbach, Hans E Völcker.

Medical photographers: Martin Kerber, Holger Weiss.

Clinic coordinator: Claudia Weber.

Center for Eye Research, Melbourne University Department of Ophthalmology, Melbourne, Australia

Investigators: Robyn H Guymer (Principal Investigator), Penelope J Allen.

Clinic coordinator: Melinda S Cain.

Visual acuity monitor: Chi D Luu.

Medical photographer: Andrew Newton.

Moorfields Eye Hospital, London, United Kingdom

Investigators: Sarah L Owens (Principal Investigator), Robyn H Guymer, Heather Jackson, Alan C Bird.

Medical photographers: Chiara Contrino, Lawrence Lane, Richard Leung, Catherine Martin, Richard Poynter, Kulwant Sehmi, Tony Sullivan, Richard Waters.

Optometrists: Michael Crossland, Lisa Donaldson, Catherine Grigg, Jane MacNaughton, Andrew Milliken, Jane Mitty, Polly Pinto, Lisa Pullham, Anthea Reid.

Clinic coordinator: Alan J Brannon.

Statisticians: Catey Bunce, Richard Wormald.

Southampton Eye Unit, Southampton General Hospital, Southampton, United Kingdom

Investigators: Iain H Chisholm (Principal Investigator), John Downie, Anne Reck.

Medical photographer: Tim Mole.

Optometrists: Bish Ashleigh, Ehab Wasfi.

Clinic coordinator: Kay Parish.

Nursing staff: Sheila Bryant, Pat Simons, Jackie Haugh.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Owens, S., Bunce, C., Brannon, A. et al. Prophylactic laser treatment appears to promote choroidal neovascularisation in high-risk ARM: results of an interim analysis. Eye 17, 623–627 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6700442

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6700442

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Subthreshold laser treatment in retinal diseases: a mini review

Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology (2024)

-

Laser and anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment for drusenoid pigment epithelial detachment in age-related macular degeneration

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Prophylactic laser in age-related macular degeneration: the past, the present and the future

Eye (2018)

-

Laser photocoagulation as treatment of non-exudative age-related macular degeneration: state-of-the-art and future perspectives

Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology (2018)