Abstract

Purpose To describe an active inflammatory cause of pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy.

Methods A 54-year-old female patient presented with complaints of worsening visual acuity and poor night vision was examined. Fundus examination was performed and color fundus photographs were taken. In addition to fluorescein angiography, visual field examinations and electroretinographic tests were performed. Macular evaluation was performed with optical coherence tomography.

Results Both fundi showed circumscribed patches of retinochoroidal atrophy and pigmentation along the retinal veins. She had also marked vitreous cells with snow ball opacities and cystoid macular edema in both eyes. Fluorescein angiography confirmed the presence of a hyperfluorescence due to widespread paravenous retinal pigment epithelial defect while ICG angiography disclosed hypofluorescence in all phases. The electroretinogram showed reduced responses especially in the left eye. Visual field tests showed scotomas corresponding with areas of atrophy along the retinal veins.

Conclusions This is a report of the findings in pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy that is a nonspecific degenerative disease and may occur in association with systemic infections or inflammation. Ocular inflammation with cystoid macular edema is an unusual manifestation of the disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy (PPRA) is an uncommon disease characterised by paravenous zones of retinal degeneration with bone spicule pigmentation.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 This is an asymptomatic disease usually detected during routine ophthalmic examination. The condition is generally bilateral and young adults are most commonly affected. The cause of the disease is unknown although an inflammatory10 or hereditary11 aetiology has been suggested. We report a case with typical fundus appearance of paravenous pigmented retinochoroidal atrophy accompanied by an active inflammation with cystoid macular edema.

Case report

A 54-year-old woman, first seen in December 1999, presented with complaints of worsening visual acuity and poor night vision for 1.5 years. The review of her medical history indicated that she had diabetes mellitus and systemic hypertension for 2 years.

Ophthalmic examination revealed that her best corrected visual acuity was RE: 8/10 and LE: 3/10. External examination was normal and extraocular motility was full. Slit-lamp examination disclosed marked cells and snowball opacities in the vitreous of both eyes. Intraocular pressure was 15 mmHg in each eye. Fundus examination showed circumscribed patches of retinochoroidal atrophy and pigmentation along the retinal veins and cystoid macular edema in both eyes.

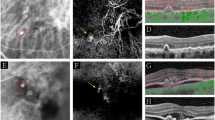

Fluorescein angiography showed diffuse window defects with hyperfluorescence consistent with retinal pigment epithelial degeneration, blocking of the fluorescence in the areas of pigment clumping along retinal vessels (Figure 1) and cystoid macular edema in both eyes (Figure 2a, b). Cystoid macular edema was also demonstrated with optical coherence tomography in both eyes (Figure 3).

Colour vision with Ishihara Pseudoisochromatic plates was normal in each eye. Humprey field analyser showed scotomas corresponding with areas of atrophy along the retinal veins.

Electrophysiological tests were performed showing reduced a and b wave amplitudes in rod response (scotopic ERG) and maximal combined response. Pattern VEP showed minimal decrease of amplitude and increase in latency in the left eye in comparison to the right eye, however the values for both eyes fell within the normal range for a patient of this age. Pattern ERG showed reduced N95 amplitude in the left eye (3.6 μV in the right and 2.2 μV in the left). PVEP and PERG findings showed ganglion cell involvement in the left eye in comparison to the right eye. There was a subnormal ratio of light peak/dark trough voltage in electrooculogram suggesting dysfunction in the region of RPE in both eyes.

No systemic abnormality was found. Results of laboratory studies including complete blood cell counts, serum electrolytes, serum protein electrophoresis, erythrocyte sedimentation rate were within normal range. Tuberculin skin test was 15 mm. There was no serologic evidence of syphilis, toxoplasmosis, systemic lupus eritematosis. Serum antibody levels for HSV I-II, CMV, rubella and measles were all negative.

During the follow-up period of 12 months, there was no change in cystoid macular edema and the fundus appearance although we treated the patient with corticosteroids and acetozolamide.

Discussion

The diagnosis of PPRA is based on a typical and characteristic fundus appearance such as: areas of atrophy of the retina, pigment epithelium, and choriocapillaris around the optic disc and along the retinal veins, bone corpuscle pigment accumulation along the distribution of retinal veins. Fluorescein angiography, electrophysiological tests and visual fields may confirm the diagnosis.

The patient described here showed bilateral cystoid macular edema and perivenous aggregations of pigment clumps associated with peripapillary and radial zones of chorioretinal atrophy. This fundus appearance was characteristic of pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy. The association of active inflammation with cystoid macular edema, however was unique in this case. There have been limited number of reports of active inflammation with this disease. Yamaguchi et al reported a 47-year-old Japanese man who had a progressive degeneration of the retina and choroid along the retinal veins associated with uveitis of 2 years’ duration.10 Haustrate and Osterhuis reported five patients with PPRA and in one patient they observed signs of active uveitis and progression of fundus lesions.3 Macular involvement is very rare in this disease. Bilateral macular coloboma was reported by Chen et al in a 23-year-old woman.12 Our case had bilateral cystoid macular edema which was one of the manifestations of active inflammation, and as far as we are aware this has not been previously reported. Fluorescein angiography gave a better definition of the lesions as well as cystoid macular edema. Optical coherence tomography revealed large cystoid areas in macular cross-sections. In PPRA it is likely that the fundus lesions may be slowly progressive4,8,13 and that the fundus resembles retinitis pigmentosa with time. In a few patients, the fundus condition may be progressive and may be detected at an older age.5 In our case during the 9 months follow-up period, we did not observe progression in fundus lesions. Macular edema did not resolve despite treatment with steroids and acetozolamide.

The aetiology of this disease is unknown. However some authors suggest a congenital origin9,11 and others a primary retinal degeneration.1 Chen et al reported a case with bilateral macular coloboma, PPRA and negative laboratory examinations and he speculated that it was a developmental abnormality in nature.12 Some reports suggest an inflammatory cause. Syphilitic aetiology has been suggested by Chi Hsin-Hsiang.14 Scheie15 described a case with rubeola retinopathy which progressed to the stage of secondary pigmentary degeneration of the retina and later Foxman et al16 examined the same patient at the age of 36. Our patient did not have a systemic abnormality according to her medical history and laboratory evaluation.

The differential diagnosis includes both chorioretinal degeneration and inflammatory disease that cause chorioretinal atrophy, such as helicoid peripapillary chorioretinal atrophy, proliferating choroiditis, angioid streaks, gyrate atrophy choroideraemia, Wagner’s dominant vitreoretinal degeneration, sarcoidosis, syphilis, acute retinal necrosis, CMV retinitis, tuberculous disseminated choroiditis, onchocerciasis, toxoplasmosis and frosted branch angiitis.

In conclusion, PPRA is a nonspecific degenerative disease that may occur in association with systemic infections or inflammation. Ocular inflammation with cystoid macular edema is an unusual manifestation of the disease.

References

Noble KG, Carr RE . Pigmented paravenous chorioretinal atrophy. Am J Ophthalmol 1983; 96: 338–344

Rothberg DS, Cibis GW, Trese M . Paravenous pigmentary retinochoroidal atrophy. Ann Ophthalmol 1984; 16: 643–646

Haustrate FMRJ, Oosterhuis JA . Pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy. Doc Ophthalmol 1986; 63: 209–237

Klop K, Van Schooneveld MJ . Pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy: a nosologic entity?. Doc Ophthalmol 1988; 70: 185–193

Hayasaka S, Shibasaki H, Noda S, Fujii M, Setogawa T . Pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy in a 68-year-old man. Ann Ophthalmol 1991; 23: 177–180

Parafita M, Diaz A, Torrijos IG, Gomez-Ulla F . Pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy. Optometry and Vision Science 1993; 70: 75–78

Pearlman JT, Kamin DF, Kopelow SM, Saxton J . Pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy. Am J Ophthalmol 1975; 80: 630–635

Pearlman JT, Heckenlively JR, Bastek JV . Progressive nature of paravenous chorioretinal atrophy. Am J Ophthalmol 1978; 85: 215–217

Small KW, Anderson WB . Pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy discordant expression in monozygotic twins. Arch Ophthalmol 1991; 109: 1408–1410

Yamaguchi K, Hara S, Tanifuji Y, Tamai M . Inflammatory pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy. Br J Ophthalmol 1989; 73: 463–467

Skalka HW . Hereditary pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy. Am J Ophthalmol 1979; 87: 286–291

Chen MS, Yang CH, Huang JS . Bilateral macular coloboma and pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy. Br J Ophthalmol 1992; 76: 250–251

Limaye SR, Mahmood MA . Retinal microangiopathy in pigmented paravenous chorioretinal atrophy. Br J Ophthalmol 1987; 71: 757–761

Hsin-Hsiang C . Retinochoroiditis radiata. Am J Ophthalmol 1948; 31: 1485–1487

Scheie HG, Morse PH . Rubeola retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol 1972; 88: 341–344

Foxman SG, Heckenlively JR, Sinclair SH . Rubeola retinopathy and pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy. Am J Ophthalmol 1985; 99: 605–606

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This case report was presented at the VIth Mediterranean Ophthalmological Society Congress and VIth Michealson Symposium May 21–26 2001, Jerusalem, Israel

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Batioğlu, F., Atmaca, L., Atilla, H. et al. Inflammatory pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy. Eye 16, 81–84 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6700021

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6700021