Abstract

Background:

The aim of this study is to elucidate the expression patterns of GATA transcription factors in neuroblastoma and the developing sympathetic nervous system (SNS).

Methods:

GATA-2, -3 and -4 and their cofactor friend-of-GATA (FOG)-2 were investigated in primary neuroblastoma by immunohistochemistry, real-time RT-PCR (n=73) and microarray analysis (n=251). In addition, GATA-2, -3 and FOG-2 expression was determined by northern-blot hybridisation. In the developing murine SNS, Gata-4 and Fog-2 were examined by immunohistochemistry.

Results:

Although Gata-2, -3 and Fog-2 are expressed in the developing nervous system, Gata-4 was not detected. In contrast, protein expression of all factors was observed in human neuroblastoma. Northern-blot hybridisation and real-time RT-PCR suggested specific expression patterns of the four genes in primary neuroblastoma, but did not show unequivocal results. In the large cohort examined by microarrays, a significant association of GATA-2, -3 and FOG-2 expression with low-risk features was observed, whereas GATA-4 mRNA levels correlated with MYCN-amplification.

Conclusion:

The transcription factors GATA-2 and -3, which are essential for normal SNS development, and their cofactor FOG-2 are downregulated in aggressive but not in favourable neuroblastoma. In contrast, upregulation of GATA-4 appears to be a common feature of this malignancy and might contribute to neuroblastoma pathogenesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

GATA transcription factors comprise a family of six zinc-finger proteins regulating cell differentiation and proliferation. Initially, GATA-1, -2 and -3 have been grouped as regulators of haematopoiesis, but analyses of mutant mice with homozygous Gata-2 or Gata-3 deletion indicate their essential function also in the development of other organs, particularly the nervous system (Pandolfi et al, 1995; Zhou et al, 2000). During development, Gata-2 and -3 are expressed in different neurons of the brainstem and spinal cord, which are critical for the generation and differentiation of sympathetic neurons (Pandolfi et al, 1995; Nardelli et al, 1999; Lim et al, 2000; Zhou et al, 2000; Tsarovina et al, 2004). In contrast, GATA-4, -5 and -6 are predominantly implicated in heart and gut development (Laverriere et al, 1994; Molkentin, 2000). In the normal brain, Gata-4 expression has only been described in migrating gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)-secreting neurons (Lawson and Mellon, 1998). However, Gata-4 could not be detected in the adult CNS (Lawson and Mellon, 1998). It has recently been demonstrated that a 5-kb proximal promoter of Gata-4 can drive reporter gene expression in migratory neural crest cells. Yet, endogenous Gata-4 has not been detected (Pilon et al, 2008). In other reports, Gata-4 expression has been described in some neural crest-derived cardiac progenitors (Tomita et al, 2005) and in primitive neural stem cell spheres (Hitoshi et al, 2004).

Although primarily considered as important transcriptional regulators during embryogenesis, GATA-2, -3 and -4 have also been associated with tumours. They have been suggested both as tumour suppressors and oncogenes (Ohyashiki et al, 1996; Laitinen et al, 2000; Akiyama et al, 2003; Usary et al, 2004; Engelsen et al, 2008; Ayala et al, 2009; Thurisch et al, 2009). Thus, repression or activation of GATA function could be important for cancer biology, and the precise function may depend on cofactors and the specific cellular context.

Friend-of-GATA (FOG) proteins are important cofactors for GATA transcription factors. In vitro, all GATA factors can interact with FOG-2 (Cantor and Orkin, 2005). FOG-2 may act as a coactivator or corepressor depending on the cell type and the promoter (Holmes et al, 1999; Lu et al, 1999; Svensson et al, 1999). During development, Fog-2 is expressed in a variety of tissues including the heart and the brain (Cantor and Orkin, 2005). From E11.5 on, it has also been detected in the ganglia of the peripheral nervous system (Tevosian et al, 1999). In an adult, FOG-2 is predominantly expressed in the heart, the brain and the testis (Holmes et al, 1999; Lu et al, 1999; Svensson et al, 1999; Tevosian et al, 1999), and has been described in tumours (Laitinen et al, 2000).

Neuroblastoma is the most common extra-cranial solid tumour in childhood. The tumours arise from neural crest cells of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and are highly heterogeneous in nature and clinical behaviour. Although younger patients with localised tumours and those with stage 4S disease have an excellent prognosis and often follow spontaneous regression, the outcome of older patients with disseminated disease (stage 4) is still very poor despite intensive multimodal treatment (Maris et al, 2007). Although the exact mechanisms leading to the divergent neuroblastoma phenotypes have yet not been characterised, it has been noticed that markers of neuronal differentiation are downregulated in unfavourable tumours (Ohira et al, 2003; Nakagawara, 2004; Fischer et al, 2006). From these data it has been suggested that de-regulation of normal developmental pathways may contribute to the pathogenesis of the biologically distinct neuroblastoma subtypes.

As GATA transcription factors are involved in both tumourigenesis and SNS development, we aimed at characterising the expression patterns of GATA-2, -3, -4 and FOG-2 in primary human neuroblastoma and in neuronal development of mice to evaluate their possible implication in human neuroblastoma.

Materials and methods

Neuroblastoma patients and tissue specimens

Neuroblastoma tissue specimens and RNA samples of 251 patients, who were enrolled in the German Neuroblastoma Trials NB90-NB2004, were obtained from the neuroblastoma tumour repository of the German Competence Net Pediatric Oncology und Hematology. Biopsy specimens were taken before the cytotoxic treatment. Informed consent was obtained from all patients. Age at diagnosis ranged from 0 to 296 months (median 15 months). The median follow-up of patients without fatal event was 6.15 years. Tumour stage was determined according to the criteria of the International Neuroblastoma Staging System (INSS). Stage distribution of the patients is as follows: stage 1, n=69; stage 2, n=44; stage 3, n=40; stage 4, n=67; and stage 4S, n=31. At diagnosis, 94 patients were <1 year, whereas 157 were older than 1 year. Amplification of the MYCN oncogene was analysed by fluorescence in situ hybridisation and detected in 33 out of 251 neuroblastomas. Molecular classification according to gene expression profiles determined by oligonucleotide-microarrays (Oberthuer et al, 2006) separated the cohort into 82 high-risk and 169 low-risk patients.

Immunohistochemistry

The expression patterns of Gata-4 and Fog-2 protein were analysed by immunohistochemistry in cryosections from CD1 mice. The day of vaginal plug was defined as E0.5. Approval for animal studies was given by the Institutional Review Board (T 0152/05). Embryos were fixed in 4% PFA (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie, Munich, Germany). Before fixation, embryos older than E15 and pups were additionally perfused under lethal anaesthesia. Tissue was embedded in Cryo-M-Bed (Bright Instrument, Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire, UK) and sectioned at 14 μm. The sections were washed in PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie), then blocked in PBS containing 0.1% BSA Fraction V (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany), 10% FBS, 0.1% Triton X-100 and 0.05% sodium azide at room temperature for 1 h and incubated with the primary antibody at 4°C overnight. After three washes, sections were incubated with the secondary antibody for 2 h at room temperature and counterstained with DAPI (0.2 mg ml−1 in PBST for 5 min; Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Sections of human neuroblastoma tissue were fixed with 4% PFA for 10 min, then washed, permeabilised and stained.

Primary antibodies: anti-GATA-2 (sc-1235), anti-GATA-3 (sc-1236), anti-GATA-4 (sc-25310, all Santa-Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA; 1 : 200), anti-β III Tubulin (TUJ-1) (ab53234, Abcam, Cambridge, UK; 1 : 500) and anti-FOG-2 (sc-10755, Santa-Cruz Biotechnology; 1 : 500). Secondary antibodies: Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-goat IgG (A11055, Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany), Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-mouse IgG2a (A21135, Invitrogen), Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG1 (A21121, Invitrogen) and Cy3 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (711-165-152, Jackson Immunoresearch Europe, Suffolk, UK) diluted 1 : 500–1 : 5000.

Negative controls were treated in parallel with only a secondary antibody. Microscopic observations were carried out under an epifluorescence microscope (AxioPlan 2 Imaging System, Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Photographs were taken with a digital camera (AxioCAM MRc; Carl Zeiss) and AxioVision 4.2 software (Carl Zeiss).

Northern blot, real-time RT-PCR and western blot were carried out as described in the Supplementary material.

Microarray analyses

Gene expression analyses were carried out using oligonucleotide-microarrays (Oberthuer et al, 2006). Expression profiles were generated in dye-flipped duplicates in dual-colour experiments. In brief, 1 μg of linearly amplified Cy3- and Cy5-labelled cRNA was hybridised together with 1 μg of reverse colour Cy-labelled reference cRNA to a customised 11 kb oligonucleotide-microarray (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany). Quality control of raw data was carried out using the software package arrayMagic (Buness et al, 2005). After normalisation of the expression profiles using the variance stabilisation algorithm (Huber et al, 2002), data from dye-flipped chip pairs were averaged to yield one intensity value for every gene probe of each patient. All microarray data are available at the ArrayExpress database (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress; Accession: E-TABM-38).

Statistics

Statistics for the microarray analyses were carried out using the nonparametric Mann–Whitney test; P-values <0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

GATA-4 and FOG-2 as well as GATA-2 and -3 are expressed in human neuroblastoma

To determine whether the transcription factors GATA-2, -3 and -4 and their cofactor FOG-2 were expressed in human neuroblastoma, expression of these proteins was analysed in primary tumours by immunohistochemistry. We detected GATA-4 and FOG-2 protein (Figure 1A) as well as GATA-2 and -3 protein (Figure 1B) in the cell nuclei. Morphological analysis was performed using H&E staining.

Gata-4 is expressed neither in the developing and adult brain nor in the developing SNS

Although the relevance of GATA-2 and -3 for the development of the central and peripheral nervous system has been well characterised (Pandolfi et al, 1995; Nardelli et al, 1999; Lim et al, 2000; Zhou et al, 2000; Tsarovina et al, 2004), it is not known whether GATA-4 contributes to these processes. We therefore analysed the developing murine brain and SNS for Gata-4 expression using immunohistochemistry. At E9.5 (Figure 2 left panel), there was no Gata-4 in neural crest cells migrating from the closing neural tube, as well as in the dorsal root ganglion. In addition, no Gata-4 was detected in the facio-acoustic and the trigeminal neural crest complexes. The spinal cord, the hindbrain and pons were also Gata-4-negative. At E11.5 (Figure 2 right panel), there was no Gata-4 in the cervical region, including the neural tube, dorsal root ganglia and sympathetic ganglia. Trigeminal ganglia were also negative. There was no labelling in the spinal cord and the thalamus. Sections of the heart (myocardium) served as positive controls and β-tubulin for demarcation of areas containing immature neurons. In addition, Gata-4 was undetectable in structures of the SNS at E17.5 and in the brain from E11.5–E18.5, P4.5–P8.5 and adult (not shown).

Gata-4 immunohistochemistry in the murine brain, sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and the heart. Left panel from top to bottom: double immunohistochemistry for Gata-4 and β-tubulin at E9.5 showing the closing neural tube, the cervical spinal cord, the hindbrain and pons. Right panel from top to bottom: Gata-4 and β-tubulin at E11.5 showing the cervical region, sympathetic ganglia, the ventral thalamus and a trigeminal ganglion. The heart served as a positive control. Orange frames represent magnified areas from the lower magnification above. drg: dorsal root ganglion; h: hindbrain; n: notochord; nc: neural crest; ncc: facio-acoustic (VII–VIII) neural crest complex; nt: neural tube; ov: otic vesicle; p: pons; tnc: trigeminal (V) neural crest tissue; sc: spinal cord; sg: sympathetic ganglion; st: sympathetic trunk; III: third ventricle; IV: fourth ventricle; *ventral root. Bars equal 100 μm.

Fog-2 is expressed in migrating neural crest cells

As FOG-2 is an important cofactor for GATA transcription factors, we were also interested if Fog-2 was expressed in the developing PNS. By immunohistochemistry, we found Fog-2-positive migratory neural crest cells and some post-mitotic neurons in the ventral spinal cord at E10.5 (Figure 3A and B). However, there was no labelling within the dorsal root and sympathetic ganglia (Figure 3A). In addition, Fog-2 was not expressed in ventral sympathetic ganglia (Figure 3C), in contrast to the medial portion of the facio-acoustic ganglion (Figure 3D). Fog-2 staining in migratory neural crest was confirmed at E11.5, as well as the absence of Fog-2 in dorsal root ganglia (data not shown). At E13.5, dorsal root and sympathetic ganglia were also negative (Figure 3E–F).

Friend-of-GATA (Fog)-2 protein detection in the neural crest and its derivatives at E10.5 and E13.5. (A–D) E10.5 and (E–F) E13.5. Each panel is represented as single and double-stained slide: (A–F) Fog-2 immunohistochemistry (red), (A′–F′) double immunohistochemistry of Fog-2 (red) with β-tubulin (green) to visualise neuronal projections. (A, A′) The spinal area. (B, B′) The dorsal spinal cord with migratory neural crest cells. (C, C′) The sympathetic ganglion. (D, D′) The facio-acoustic ganglion. (E, E′) The spinal cord and dorsal root ganglion. (F, F′) Sympathetic ganglia. da: dorsal aorta; drg: dorsal root ganglion; fag: facio-acoustic ganglion; mnc: migratory neural crest; n: notochord; ov: otic vesicle; sc: spinal cord; sg: sympathetic ganglion. Bars equal 100 μm.

Expression levels of GATA-2, -3, -4 and FOG-2 vary in neuroblastoma specimens

To quantify expression levels of GATA-2, -3, -4 and FOG-2 in various subtypes of neuroblastoma, we evaluated their mRNA levels. Using northern-blot analysis, consistent GATA-2, -3 and FOG-2 expressions were observed in tumours of lower stages (n=11), whereas a remarkable reduction in mRNA levels of all three genes was found in neuroblastoma of stage 4 (n=3; Supplementary figure S1). Owing to technical limitations in establishing a northern blot for GATA-4, expression levels of this gene were determined by real-time RT-PCR in a set of 73 primary tumours (Supplementary table S2). Comparisons of MYCN-nonamplified vs MYCN-amplified tumours, localised stages vs stage 4 vs stage 4S and patients below 1 vs above 1 year, did not show significantly differing expression levels. Similarly, analysis of FOG-2, GATA-2 and GATA-3 expression by real-time RT-PCR (Supplementary tables S3–S5) disclosed only lower FOG-2 levels in MYCN-amplified vs MYCN-nonamplified tumours at a significant level.

GATA-4 is highly expressed in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma

As the association of GATA expression levels and the prognostic phenotype of neuroblastoma could not unequivocally be addressed by northern blot and real-time RT-PCR, we examined GATA expression levels by microarray analysis in a larger cohort of primary neuroblastoma (n=251). In this set, we compared not only MYCN-nonamplified vs MYCN-amplified tumours, localised stages vs stage 4 vs stage 4S, patients below 1 vs above 1 year, but also high vs low-risk tumours according to a highly accurate gene expression-based classification using the PAM algorithm (Oberthuer et al, 2006). MYCN-amplified tumours (n=32 out of 33; one specimen was not available for GATA-4 analysis) expressed significantly more GATA-4 than MYCN-nonamplified (n=218) tumours (Figure 4A; P=0.001). Comparisons of tumours of different stages and from patients of varying ages did not show significant differences (Figure 4B and C), although stage 4 tumours tended to have higher transcript levels than tumours of localised stages. High-risk tumours according to the PAM classification showed significantly higher GATA-4 expression levels than low-risk tumours (Figure 4D; P=0.001).

Relative expression levels of GATA-4 and friend-of-GATA (FOG)-2 according to microarray analyses. (A–D) GATA-4 and (E–H) FOG-2. (A and E) MYCN-nonamplified (n=218) vs MYCN-amplified (n=32 for GATA-4; n=33 for FOG-2). (B and F) Localised stages (n=153) vs stage 4 (n=67) vs stage 4S (n=31). (C and G) Patients below 1 year (n=94) vs above 1 year (n=157). (D and H) High-risk (HR; n=82) vs low-risk (LR; n=169) tumours according to the PAM classification. Expression values are given in log ratios (sample vs reference RNA). Boxes: median expression values (horizontal line) and twenty-fifth and seventy-fifth percentiles; whiskers: distances from the end of the box to the largest and smallest observed values that are <1.5 box lengths from either end of the box; open circles: outlying values; asterisks: extreme values. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001 according to the nonparametric Mann–Whitney test.

To further strengthen the significance of GATA-4, protein expression levels of GATA-4 were analysed by western blot. Low- and high-expressing specimens were chosen according to microarray analyses, and protein expression levels were confirmed to correlate well with mRNA expression data (Supplementary figure S2).

High FOG-2, GATA-2 and -3 expression levels in neuroblastoma with favourable prognostic markers

FOG-2 transcript levels determined by microarrays were evaluated for the same 251 tumours. In contrast to GATA-4, tumours without MYCN-amplification exhibited higher expression values than those with MYCN-amplification (Figure 4E; P<0.001). Stage as well as age also showed significant differences in FOG-2 expression. Localised tumours and those of stage 4S had higher transcript levels than stage 4 tumours (Figure 4F; P<0.001). Tumours of younger patients (<1 year) expressed more FOG-2 compared with older patients (>1 year) (Figure 4G; P<0.001). Moreover, low-risk tumours according to the PAM classification expressed significantly more FOG-2 than high-risk neuroblastomas (Figure 4H; P<0.001).

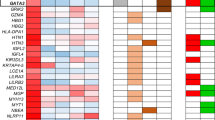

As northern blot results suggested differential GATA-2 and -3 expression in different clinical neuroblastoma subgroups (Supplementary figure S1), we also analysed their associations with tumour characteristics. Microarray analyses revealed higher transcript levels of both factors in neuroblastoma with favourable prognostic markers, similar to FOG-2. GATA-2 showed significantly higher expression values in MYCN-nonamplified compared with MYCN-amplified tumours (Figure 5A, P<0.001). GATA-3 revealed a similar trend, but not a significant association (Figure 5E). Localised neuroblastoma had higher GATA-2 and -3 expression levels than tumours of stage 4 (Figure 5B, P=0.048) and 5F (P=0.039)). Comparisons of stage 4S tumours vs stage 4 disclosed a significant association only for GATA-2 with higher transcript levels in the more favourable 4S tumours (Figure 5B; P=0.019). Younger patients had higher GATA-2 and -3 expressions than older ones (Figure 5C (P<0.001) and 5G (P=0.027)). Consistently, the PAM classification indicated significantly higher transcript levels in low-risk tumours for both GATA-2 and -3 (Figure 5D (P<0.001) and 5H (P=0.001)).

Relative expression levels of GATA-2 and -3 according to microarray analyses. (A–D) GATA-2 and (E–H) GATA-3. (A and E) MYCN-nonamplified (n=218) vs MYCN-amplified (n=33). (B and F) Localised stages (n=153) vs stage 4 (n=67) vs stage 4S (n=31). (C and G) Patients below 1 year (n=94) vs above 1 year (n=157). (D and H) High-risk (HR; n=82) vs low-risk (LR; n=169) tumours according to the PAM classification. Expression values are given in log ratios (sample vs reference RNA). Box plots represent data as in Figure 4. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001 according to the nonparametric Mann–Whitney test.

Taken together, GATA-4 expression appears to be a common feature of neuroblastoma with highest expression levels in MYCN-amplified tumours. In contrast, GATA-2, -3 and FOG-2 are preferentially expressed in neuroblastomas with favourable prognostic characteristics.

Discussion

GATA transcription factors are crucial for the normal development of a variety of tissues. In addition, they have been implicated in the pathogenesis of multiple malignancies. In this study, we characterise the expression patterns of GATA-2, -3, -4 and FOG-2 in murine nervous system development and primary human neuroblastoma to elucidate their potential implication in neuroblastoma pathogenesis. Although GATA-2 and -3 expression has previously been described in various neuroblastoma cell lines (Yang et al, 1994; Minegishi et al, 2005; Scherzer et al, 2008; Wallach et al, 2009), we show their expression in primary neuroblastoma for the first time. Furthermore, we demonstrate nuclear GATA-4 protein expression in human neuroblastoma cells. Concerning cofactors for GATA proteins, we also show nuclear FOG-2 expression in primary neuroblastoma. Therefore, FOG-2 is available for interaction with GATA factors.

Moreover, we show that Gata-4 is expressed neither in the developing or adult murine CNS nor in the developing murine SNS, including migratory neural crest. Apparently, GATA-4 expression only arises during tumourigenesis of neuroblastoma, suggesting that it may have a role in the pathogenesis of neuroblastoma. The absence of Gata-4 in migratory neural crest cells confirms a recent report (Pilon et al, 2008), in which whole mount in situ hybridisation failed to detect Gata-4. Pilon et al (2008) discussed the possibility of a small subset of migratory neural crest cells expressing Gata-4. In their hands, a 5-kb proximal promoter of Gata-4 can drive reporter gene expression in migratory neural crest cells at E9.5–E11.5. They discussed that Gata-4 might only be expressed in a very limited subset of likely cardiac neural crest cells. Tomita et al (2005) detected Gata-4 in neural crest-derived cardiac progenitor cells that rest as dormant stem cells in the heart. However, it could be possible that neural crest-derived cardiac progenitors only express Gata-4 when they arrive in the heart. As for primitive neural stem cells, the spheres derived from E6.5 epiblasts have also been reported to express Gata-4, in contrast to definitive neurospheres (Hitoshi et al, 2004). As epiblasts give rise to all three germ layers, it may not be surprising that Gata-4 has been detected there. Therefore, we conclude that endogenous Gata-4 is absent in sympathetic structures during mouse development, if not below the detection limit of our method.

We also analysed the expression of Fog-2 in the developing nervous system and confirmed the expression in the facio-acoustic ganglion shown by in situ hybridisation at E11.5 (Tevosian et al, 1999), but on the protein level and a day earlier in embryonic development. We further specified the staining to the medial portion of the ganglion. Yet, the dorsal root ganglion and sympathetic ganglia were clearly negative. In addition, for the first time we show Fog-2 expression in migratory neural crest cells that may give rise to neuroblastoma. During normal development, FOG-2 might interact with GATA-2 and/or GATA-3, as all three factors are expressed in neural crest derivatives (Tevosian et al, 1999; Tsarovina et al, 2004).

This allows to conclude that during the development of the nervous system, the four factors investigated show a distinct expression pattern with Gata-4 being unique because of its complete absence. Next, we performed quantitative expression analyses of all four factors in neuroblastoma. Northern blot analysis and real-time RT-PCR of 14 and 73 specimens, respectively, suggested different expression levels in distinct neuroblastoma subgroups of all factors. To evaluate these observations, we used microarray data of 251 primary neuroblastomas, and compared the expression levels of GATA-2, -3, -4 and FOG-2 in different clinico-genetic subgroups. It should be noted that we found significantly higher GATA-4 expression levels in the unfavourable subgroups of MYCN-amplified tumours and of neuroblastoma with unfavourable PAM prediction (Figure 4). This finding is similar to ovarian granulosa cell tumours, where a high GATA-4 expression is associated with aggressive behaviour (Anttonen et al, 2005). In mucinous ovarian carcinoma, however, nuclear localisation of GATA-4 correlated negatively with the grade and stage of tumours (Lassus et al, 2001). In neuroblastoma, no significant correlation was observed with stage of the disease, although localised tumours tended to have lower GATA-4 expression than those of disseminated stages 4 and 4S (Figure 4B). In addition, age at diagnosis had no influence on GATA-4 expression levels. Together, these findings support the notion that GATA-4 is specifically upregulated in neuroblastoma pathogenesis instead of being expressed in progenitor cells of the developing sympathetic system. So far, our microarray analyses suggest higher GATA-4 expression levels in more aggressive tumours.

It is interesting to note that the GATA cofactor FOG-2 as well as GATA-2 and -3 behave oppositely to GATA-4. The expression of FOG-2 was higher in tumours without MYCN-amplification and in tumours with favourable PAM prediction. In contrast to GATA-4, FOG-2 expression did depend on both stage of the tumour and age at diagnosis. Localised tumours and those of stage 4S had higher transcript levels than stage 4 tumours, and tumours of younger patients expressed higher levels of FOG-2 compared with older patients (Figure 4). In breast cancer, FOG-2 expression is also correlated with favourable prognosis, likely as it is required for the normal expression of its downstream target genes Esr1 and Foxa1 (Manuylov et al, 2007). Whether FOG-2 is involved in the processes of spontaneous regression in neuroblastoma by supporting cellular differentiation as in breast cancer still remains to be elucidated.

The expression levels of GATA-2 and -3 were also higher in the more favourable subtypes of neuroblastoma (Figure 5). Both were more highly expressed in localised tumours (vs stage 4), younger patients and tumours with favourable PAM prediction. In addition, significantly higher expression values were also found for GATA-2 in tumours without MYCN-amplification and stage 4S tumours (vs stage 4). In an attempt to select genes for prognosis prediction in neuroblastoma, among other genes GATA-2 has been observed to be associated with favourable prognosis (Ohira et al, 2005), which is strengthened by our detailed analysis. In patients with acute myeloid leukaemia, GATA-2 was rather associated with poor prognosis (Ohyashiki et al, 1996), although this correlation is challenged by a recent report (Ayala et al, 2009). In breast cancer, high GATA-3 expression correlates with low tumour grade and slow proliferation rates (Usary et al, 2004; Mehra et al, 2005), corresponding to our results. In this malignancy, silencing of GATA-3 is not the primary molecular mechanism that leads to the GATA-3-negative state. Rather, proliferation of GATA-3-negative stem cell-like cells may cause tumour progression (Kouros-Mehr et al, 2008). Moreover, using a retroviral delivery strategy Kouros-Mehr et al (2008) proved that Gata-3 is sufficient to induce differentiation in breast cancer. This raises the question on upstream regulators of GATA-3 signalling; candidates may be members of the Wnt genes (Davidson et al, 2002). However, GATA-3 has also been identified as a marker of an aggressive phenotype and poor prognosis in endometrial cancer (Engelsen et al, 2008). Thus, GATA factors have been associated with favourable or unfavourable tumours, depending on the type of cancer. In neuroblastoma, favourable tumour subtypes have been described to be more differentiated on the molecular level (Ohira et al, 2003; Nakagawara, 2004; Fischer et al, 2006). Accordingly, GATA-2 overexpression has been shown to cause differentiation of human neuroblastoma SK-N-BE2 cells (Kaneko et al, 2006). In addition, Gata-2 overexpression arrested the proliferation of mouse neuroblastoma cells (NB2a), yet without induction of differentiation (El Wakil et al, 2006). In this context, GATA-2 may act on regulators of cell cycle components and/or shut-off the Notch pathway (El Wakil et al, 2006). Although FOG-2 is likely to interact with any GATA protein, our data obtained in neuroblastoma specimens suggest a predominant interaction with GATA-2 and/or GATA-3; in addition, the interaction between FOG-2 and GATA-4 could be disturbed.

The observation of concordant expression of Gata-2, -3 and Fog-2 in the ganglia of neural crest origin (Tevosian et al, 1999; Tsarovina et al, 2004), migrating neural crest cells (Fog-2; Figure 3) and favourable neuroblastoma supports the hypothesis that developmental molecular pathways are intact in this subtype of neuroblastoma. Accordingly, the low expression levels of these genes in unfavourable neuroblastoma are in line with a loss of differentiation pathways in these tumours. Moreover, the strong correlation of FOG-2 with favourable markers suggests its possible involvement in the development of a regressive phenotype. In contrast, the finding of GATA-4 expression in primary neuroblastoma, but not in cells of the developing nervous system, indicates its unique role in neuroblastoma pathogenesis.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Akiyama Y, Watkins N, Suzuki H, Jair KW, van Engeland M, Esteller M, Sakai H, Ren CY, Yuasa Y, Herman JG, Baylin SB (2003) GATA-4 and GATA-5 transcription factor genes and potential downstream antitumor target genes are epigenetically silenced in colorectal and gastric cancer. Mol Cell Biol 23: 8429–8439

Anttonen M, Unkila-Kallio L, Leminen A, Butzow R, Heikinheimo M (2005) High GATA-4 expression associates with aggressive behavior, whereas low anti-Mullerian hormone expression associates with growth potential of ovarian granulosa cell tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90: 6529–6535

Ayala RM, Martinez-Lopez J, Albizua E, Diez A, Gilsanz F (2009) Clinical significance of Gata-1, Gata-2, EKLF, and c-MPL expression in acute myeloid leukemia. Am J Hematol 84: 79–86

Buness A, Huber W, Steiner K, Sültmann H, Poustka A (2005) arrayMagic: two-colour cDNA microarray quality control and preprocessing. Bioinformatics 21: 554–556

Cantor AB, Orkin SH (2005) Coregulation of GATA factors by the Friend of GATA (FOG) family of multitype zinc finger proteins. Semin Cell Dev Biol 16: 117–128

Davidson EH, Rast JP, Oliveri P, Ransick A, Calestani C, Yuh CH, Minokawa T, Amore G, Hinman V, Arenas-Mena C, Otim O, Brown CT, Livi CB, Lee PY, Revilla R, Rust AG, Pan Z, Schilstra MJ, Clarke PJ, Arnone MI, Rowen L, Cameron RA, McClay DR, Hood L, Bolouri H (2002) A genomic regulatory network for development. Science 295: 1669–1678

El Wakil A, Francius C, Wolff A, Pleau-Varet J, Nardelli J (2006) The GATA2 transcription factor negatively regulates the proliferation of neuronal progenitors. Development 133: 2155–2165

Engelsen IB, Stefansson IM, Akslen LA, Salvesen HB (2008) GATA3 expression in estrogen receptor alpha-negative endometrial carcinomas identifies aggressive tumors with high proliferation and poor patient survival. Am J Obstet Gynecol 199: 543 e541-547

Fischer M, Oberthuer A, Brors B, Kahlert Y, Skowron M, Voth H, Warnat P, Ernestus K, Hero B, Berthold F (2006) Differential expression of neuronal genes defines subtypes of disseminated neuroblastoma with favorable and unfavorable outcome. Clin Cancer Res 12: 5118–5128

Hitoshi S, Seaberg RM, Koscik C, Alexson T, Kusunoki S, Kanazawa I, Tsuji S, van der Kooy D (2004) Primitive neural stem cells from the mammalian epiblast differentiate to definitive neural stem cells under the control of Notch signaling. Genes Dev 18: 1806–1811

Holmes M, Turner J, Fox A, Chisholm O, Crossley M, Chong B (1999) hFOG-2, a novel zinc finger protein, binds the co-repressor mCtBP2 and modulates GATA-mediated activation. J Biol Chem 274: 23491–23498

Huber W, von Heydebreck A, Sültmann H, Poustka A, Vingron M (2002) Variance stabilization applied to microarray data calibration and to the quantification of differential expression. Bioinformatics 18 (Suppl 1): S96–S104

Kaneko M, Yang W, Matsumoto Y, Watt F, Funa K (2006) Activity of a novel PDGF beta-receptor enhancer during the cell cycle and upon differentiation of neuroblastoma. Exp Cell Res 312: 2028–2039

Kouros-Mehr H, Bechis SK, Slorach EM, Littlepage LE, Egeblad M, Ewald AJ, Pai SY, Ho IC, Werb Z (2008) GATA-3 links tumor differentiation and dissemination in a luminal breast cancer model. Cancer Cell 13: 141–152

Laitinen MP, Anttonen M, Ketola I, Wilson DB, Ritvos O, Butzow R, Heikinheimo M (2000) Transcription factors GATA-4 and GATA-6 and a GATA family cofactor, FOG-2, are expressed in human ovary and sex cord-derived ovarian tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85: 3476–3483

Lassus H, Laitinen MP, Anttonen M, Heikinheimo M, Aaltonen LA, Ritvos O, Butzow R (2001) Comparison of serous and mucinous ovarian carcinomas: distinct pattern of allelic loss at distal 8p and expression of transcription factor GATA-4. Lab Invest 81: 517–526

Laverriere AC, MacNeill C, Mueller C, Poelmann RE, Burch JB, Evans T (1994) GATA-4/5/6, a subfamily of three transcription factors transcribed in developing heart and gut. J Biol Chem 269: 23177–23184

Lawson MA, Mellon PL (1998) Expression of GATA-4 in migrating gonadotropin-releasing neurons of the developing mouse. Mol Cell Endocrinol 140: 157–161

Lim KC, Lakshmanan G, Crawford SE, Gu Y, Grosveld F, Engel JD (2000) Gata3 loss leads to embryonic lethality due to noradrenaline deficiency of the sympathetic nervous system. Nat Genet 25: 209–212

Lu JR, McKinsey TA, Xu H, Wang DZ, Richardson JA, Olson EN (1999) FOG-2, a heart- and brain-enriched cofactor for GATA transcription factors. Mol Cell Biol 19: 4495–4502

Manuylov NL, Smagulova FO, Tevosian SG (2007) Fog2 excision in mice leads to premature mammary gland involution and reduced Esr1 gene expression. Oncogene 26: 5204–5213

Maris JM, Hogarty MD, Bagatell R, Cohn SL (2007) Neuroblastoma. Lancet 369: 2106–2120

Mehra R, Varambally S, Ding L, Shen R, Sabel MS, Ghosh D, Chinnaiyan AM, Kleer CG (2005) Identification of GATA3 as a breast cancer prognostic marker by global gene expression meta-analysis. Cancer Res 65: 11259–11264

Minegishi N, Suzuki N, Kawatani Y, Shimizu R, Yamamoto M (2005) Rapid turnover of GATA-2 via ubiquitin-proteasome protein degradation pathway. Genes Cells 10: 693–704

Molkentin JD (2000) The zinc finger-containing transcription factors GATA-4, -5, and -6. Ubiquitously expressed regulators of tissue-specific gene expression. J Biol Chem 275: 38949–38952

Nakagawara A (2004) Neural crest development and neuroblastoma: the genetic and biological link. Prog Brain Res 146: 233–242

Nardelli J, Thiesson D, Fujiwara Y, Tsai FY, Orkin SH (1999) Expression and genetic interaction of transcription factors GATA-2 and GATA-3 during development of the mouse central nervous system. Dev Biol 210: 305–321

Oberthuer A, Berthold F, Warnat P, Hero B, Kahlert Y, Spitz R, Ernestus K, Konig R, Haas S, Eils R, Schwab M, Brors B, Westermann F, Fischer M (2006) Customized oligonucleotide microarray gene expression-based classification of neuroblastoma patients outperforms current clinical risk stratification. J Clin Oncol 24: 5070–5078

Ohira M, Morohashi A, Inuzuka H, Shishikura T, Kawamoto T, Kageyama H, Nakamura Y, Isogai E, Takayasu H, Sakiyama S, Suzuki Y, Sugano S, Goto T, Sato S, Nakagawara A (2003) Expression profiling and characterization of 4200 genes cloned from primary neuroblastomas: identification of 305 genes differentially expressed between favorable and unfavorable subsets. Oncogene 22: 5525–5536

Ohira M, Oba S, Nakamura Y, Isogai E, Kaneko S, Nakagawa A, Hirata T, Kubo H, Goto T, Yamada S, Yoshida Y, Fuchioka M, Ishii S, Nakagawara A (2005) Expression profiling using a tumor-specific cDNA microarray predicts the prognosis of intermediate risk neuroblastomas. Cancer Cell 7: 337–350

Ohyashiki K, Ohyashiki JH, Shimamoto T, Toyama K (1996) Pattern of expression and their clinical implications of the GATA family, stem cell leukemia gene, and EVI1 in leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes. Leuk Lymphoma 23: 431–436

Pandolfi PP, Roth ME, Karis A, Leonard MW, Dzierzak E, Grosveld FG, Engel JD, Lindenbaum MH (1995) Targeted disruption of the GATA3 gene causes severe abnormalities in the nervous system and in fetal liver haematopoiesis. Nat Genet 11: 40–44

Pilon N, Raiwet D, Viger RS, Silversides DW (2008) Novel pre- and post-gastrulation expression of Gata4 within cells of the inner cell mass and migratory neural crest cells. Dev Dyn 237: 1133–1143

Scherzer CR, Grass JA, Liao Z, Pepivani I, Zheng B, Eklund AC, Ney PA, Ng J, McGoldrick M, Mollenhauer B, Bresnick EH, Schlossmacher MG (2008) GATA transcription factors directly regulate the Parkinson′s disease-linked gene alpha-synuclein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 10907–10912

Svensson EC, Tufts RL, Polk CE, Leiden JM (1999) Molecular cloning of FOG-2: a modulator of transcription factor GATA-4 in cardiomyocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 956–961

Tevosian SG, Deconinck AE, Cantor AB, Rieff HI, Fujiwara Y, Corfas G, Orkin SH (1999) FOG-2: A novel GATA-family cofactor related to multitype zinc-finger proteins Friend of GATA-1 and U-shaped. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 950–955

Thurisch B, Liang S, Sarioglu N, Schomburg L, Bungert J, Dame C (2009) Transgenic mice expressing small interfering RNA against Gata4 point to a crucial role of Gata4 in the heart and gonads. J Mol Endocrinol (E-pub ahead of print 2 June 2009, doi:10.1677/JME-109-0030)

Tomita Y, Matsumura K, Wakamatsu Y, Matsuzaki Y, Shibuya I, Kawaguchi H, Ieda M, Kanakubo S, Shimazaki T, Ogawa S, Osumi N, Okano H, Fukuda K (2005) Cardiac neural crest cells contribute to the dormant multipotent stem cell in the mammalian heart. J Cell Biol 170: 1135–1146

Tsarovina K, Pattyn A, Stubbusch J, Müller F, van der Wees J, Schneider C, Brunet JF, Rohrer H (2004) Essential role of Gata transcription factors in sympathetic neuron development. Development 131: 4775–4786

Usary J, Llaca V, Karaca G, Presswala S, Karaca M, He X, Langerod A, Karesen R, Oh DS, Dressler LG, Lonning PE, Strausberg RL, Chanock S, Borresen-Dale AL, Perou CM (2004) Mutation of GATA3 in human breast tumors. Oncogene 23: 7669–7678

Wallach I, Zhang J, Hartmann A, van Landeghem FKH, Ivanova A, Klar M, Dame C (2009) Erythropoietin-receptor gene regulation in neuronal cells. Pediatr Res 65: 619–624

Yang Z, Gu L, Romeo PH, Bories D, Motohashi H, Yamamoto M, Engel JD (1994) Human GATA-3 trans-activation, DNA-binding, and nuclear localization activities are organized into distinct structural domains. Mol Cell Biol 14: 2201–2212

Zhou Y, Yamamoto M, Engel JD (2000) GATA2 is required for the generation of V2 interneurons. Development 127: 3829–3838

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Barbara Hero for providing clinical data and Yvonne Kahlert and Heike Düren for technical assistance (Department of Pediatric Oncology and Hematology, University Children's Hospital of Cologne, Cologne, Germany). In addition, the collaborative efforts with Dr André Oberthuer (University Children's Hospital of Cologne), Dr Frank Westermann and Dr Benedikt Brors (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum Heidelberg, Germany) in performing microarray analyses are appreciated.

The microscope and equipment used for immunohistochemical analysis and images have been funded by the Sonnenfeld Stiftung (Berlin, Germany), the Sanitätsrat Dr. Emil Alexander Hübner und Gemahlin-Stiftung (Stifterverband für die Deutsche Wissenschaft e.V., Essen), and the Verein für Frühgeborene Kinder am Virchow-Klinikum e.V. (Berlin, Germany).

Funding: The study is supported by grants from the Fritz–Thyssen–Stiftung (AZ. 10.05.2.162 to CD), the Berliner Krebsgesellschaft (DAFF200829 to CD) and the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung through the National Genome Research Network 2 (Grant No. 01GS0456 to MF and FB). Additional support has been provided by the Jürgen–Manchot–Stiftung (to CD).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on British Journal of Cancer website (http://www.nature.com/bjc)

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Hoene, V., Fischer, M., Ivanova, A. et al. GATA factors in human neuroblastoma: distinctive expression patterns in clinical subtypes. Br J Cancer 101, 1481–1489 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605276

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605276

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

TP53 and TP53-associated genes are correlated with the prognosis of paediatric neuroblastoma

BMC Genomic Data (2022)

-

Deep analysis of neuroblastoma core regulatory circuitries using online databases and integrated bioinformatics shows their pan-cancer roles as prognostic predictors

Discover Oncology (2021)

-

Analysis and identification of novel biomarkers involved in neuroblastoma via integrated bioinformatics

Investigational New Drugs (2021)

-

The Diagnostic Dilemma of GATA3 Immunohistochemistry in Pheochromocytoma and Paraganglioma

Endocrine Pathology (2020)

-

High glucose promotes pancreatic cancer cells to escape from immune surveillance via AMPK-Bmi1-GATA2-MICA/B pathway

Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research (2019)