Abstract

Background:

Few prospective studies have examined cancer incidence among vegetarians.

Methods:

We studied 61 566 British men and women, comprising 32 403 meat eaters, 8562 non-meat eaters who did eat fish (‘fish eaters’) and 20 601 vegetarians. After an average follow-up of 12.2 years, there were 3350 incident cancers of which 2204 were among meat eaters, 317 among fish eaters and 829 among vegetarians. Relative risks (RRs) were estimated by Cox regression, stratified by sex and recruitment protocol and adjusted for age, smoking, alcohol, body mass index, physical activity level and, for women only, parity and oral contraceptive use.

Results:

There was significant heterogeneity in cancer risk between groups for the following four cancer sites: stomach cancer, RRs (compared with meat eaters) of 0.29 (95% CI: 0.07–1.20) in fish eaters and 0.36 (0.16–0.78) in vegetarians, P for heterogeneity=0.007; ovarian cancer, RRs of 0.37 (0.18–0.77) in fish eaters and 0.69 (0.45–1.07) in vegetarians, P for heterogeneity=0.007; bladder cancer, RRs of 0.81 (0.36–1.81) in fish eaters and 0.47 (0.25–0.89) in vegetarians, P for heterogeneity=0.05; and cancers of the lymphatic and haematopoietic tissues, RRs of 0.85 (0.56–1.29) in fish eaters and 0.55 (0.39–0.78) in vegetarians, P for heterogeneity=0.002. The RRs for all malignant neoplasms were 0.82 (0.73–0.93) in fish eaters and 0.88 (0.81–0.96) in vegetarians (P for heterogeneity=0.001).

Conclusion:

The incidence of some cancers may be lower in fish eaters and vegetarians than in meat eaters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Vegetarians do not eat meat or fish. Meat has been suspected of influencing the risk for several types of cancer. For example, in the systematic review by the WCRF/AICR (World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research), an expert panel concluded that both red meat and processed meat are convincing causes of colorectal cancer, and that there was some evidence suggesting that high intakes of red or processed meat increased the risk for cancers of the oesophagus, stomach, pancreas, lung, endometrium and prostate (WCRF/AICR, 2007).

A few prospective studies have been established with the aim of studying the long-term health of vegetarians, and have used recruitment methods designed to ensure that a substantial number of the participants were vegetarians. Some findings on cancer incidence rates in vegetarians have been reported from the Adventist Health Study in California (Fraser, 1999), the Oxford Vegetarian Study (Sanjoaquin et al, 2004), the UK Women's Cohort Study (Taylor et al, 2007) and EPIC-Oxford (Key et al, 2009). These reports included data for only a few cancer sites. To provide more information on cancer incidence in vegetarians, in this study, we report on the incidence of malignant cancer at 20 sites or groups of sites, plus all incident malignant cancers combined, in a pooled analysis of data from two prospective studies in the United Kingdom, namely the Oxford Vegetarian Study (Appleby et al, 1999) and the EPIC-Oxford cohort (Davey et al, 2003).

Materials and methods

In the Oxford Vegetarian Study, participants were recruited throughout the United Kingdom between 1980 and 1984 (Thorogood et al, 1994). Vegetarian participants were recruited through advertisements, the news media and word of mouth, and non-vegetarian participants were recruited as friends and relatives of the vegetarian participants. A semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire was completed at the time of recruitment, and information was collected on smoking and exercise habits, alcohol drinking, social class, weight and height and reproductive factors in women. In total, 11 140 participants were recruited.

The EPIC-Oxford cohort was recruited throughout the United Kingdom between 1993 and 1999 (Davey et al, 2003). Two methods of recruitment, namely general practice (GP) recruitment and postal recruitment were used. A Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee (MREC Scotland) approved the protocol. A pilot recruitment phase was conducted by collaborating GPs in Scotland, and nurses working in GP practices in Oxfordshire, Buckinghamshire and Greater Manchester carried out further recruitment from the general population. Postal recruitment was designed to recruit as many vegetarians and vegans as possible. The main questionnaire was mailed directly to all members of The Vegetarian Society of the United Kingdom and to all surviving participants in the Oxford Vegetarian Study. Respondents were invited to give names and addresses of their relatives and friends who might also be interested in receiving a questionnaire. In addition, a short questionnaire was distributed to all members of The Vegan Society, enclosed in health/diet-interest magazines, and displayed on health food shop counters. The main questionnaire was then mailed to all those who returned a short questionnaire. A total of 7423 participants were recruited by the GP method and 58 042 participants by the postal method. The main questionnaire included a food frequency questionnaire and information on smoking and exercise habits, alcohol drinking, social class, weight and height and reproductive factors in women.

Participants in both studies were followed-up until 31 December 2006 by record linkage with the United Kingdom's National Health Service Central Register, which provides information on cancer diagnoses and all deaths. Participants in the Oxford Vegetarian Study who subsequently joined EPIC-Oxford contributed person-years in the Oxford Vegetarian Study until the date when they joined EPIC-Oxford. Malignant neoplasms were defined as codes C00-97 of the Tenth Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD; World Health Organization, 1992), excluding code C44 (non-melanoma skin cancer). In participants with no recorded incident malignant neoplasm, but for whom a malignant neoplasm was noted on the death certificate, the cancer was taken to have occurred on the date of death.

Participants were excluded from the analysis if they were aged <20 or >89 years at recruitment, or had a previous malignant neoplasm before recruitment or had no information for one or more of the factors, such as age, sex, smoking and diet group. These exclusions left 61 566 participants (15 571 men and 45 995 women) who were censored on reaching the age of 90 years. The participants included 2842 persons who contributed follow-up data from both studies. Relative risks (RRs) and their 95% confidence intervals for 20 cancer sites or groups of sites, plus all incident malignant cancers combined, were calculated by Cox proportional hazards regression with age as the underlying time variable, stratified by study protocol (Oxford Vegetarian Study participants, EPIC-Oxford GP recruited participants, EPIC-Oxford postal recruited participants) and sex (where appropriate), and were adjusted for smoking (never smoker, former smoker, <15 cigarettes per day or cigar or pipe only, 15+ cigarettes per day), alcohol consumption (<1, 1–7, 8–15, 16+ g of ethanol per day, unknown) and body mass index (BMI) (<20.0, 20.0–22.4, 22.5–24.9, 25.0–27.4, 27.5+ kg m−2, unknown), physical activity level (low, high, unknown) and, for the women-only cancers, parity (none, 1–2, 3+, unknown) and oral contraceptive use (ever, never, unknown). The diet group was classified into three categories, namely meat eaters, fish eaters (participants who did not eat meat but did eat fish) and vegetarians (participants who did not eat meat or fish). Wherever a participant could not be categorised for a given factor (usually because the appropriate section of the questionnaire was left unanswered or incomplete) they were allocated to an ‘unknown’ category for the analysis.

Statistical significance was set at the 5% level. All statistical analyses were conducted using the Stata Statistical Software: Release 10 (College Station, TX, USA: StataCorp LP).

Results

The characteristics of the participants are given in Table 1. One-third of the participants were vegetarians and three-quarters were women. The mean age at recruitment was lower in the fish eaters and vegetarians than in the meat eaters. Smoking rates were low overall, with only 14.4% of meat eaters, 11.2% of fish eaters and 11.4% of vegetarians reporting that they were smokers at the time of recruitment. The median BMI was 1.5 kg m−2 lower in vegetarians than in meat eaters, and the median alcohol consumption was 1.0 g per day lower in vegetarians than in meat eaters. Fish eaters had similar mean BMI to the vegetarians and had similar alcohol consumption to the meat eaters. The proportions of men and women who reported a relatively high level of physical activity were higher among fish eaters and vegetarians than among meat eaters. The proportion of women who were nulliparous at recruitment was higher among fish eaters and vegetarians than among meat eaters, and the proportion of women who had ever used oral contraceptives was lower among fish eaters and vegetarians than among meat eaters. Of the 2842 persons who participated both in the Oxford Vegetarian Study and EPIC-Oxford, 2337 (82%) were allocated to the same diet group at recruitment to both studies, with an average 13 years gap between recruitment dates, indicating a high level of consistency in the diet group. At recruitment, 66% of vegetarians reported that they had followed their current diet for more than 5 years.

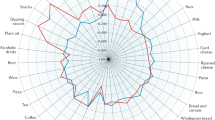

Table 2 shows the RRs for fish eaters and vegetarians relative to meat eaters for each of the 20 cancer sites or groups of sites, plus all malignant cancers combined. There were 3350 incident cancers before the age of 90 years among the participants up to 31 December 2006. All but 339 (10%) of the 3350 incident cancers are included in the 20 cancer sites or groups of sites shown in Table 2. There was significant heterogeneity between dietary groups for the following four cancer sites: stomach cancer, RRs (compared with meat eaters) of 0.29 (95% CI: 0.07–1.20) in fish eaters and 0.36 (0.16–0.78) in vegetarians, P for heterogeneity=0.007; ovarian cancer, RRs of 0.37 (0.18–0.77) in fish eaters and 0.69 (0.45–1.07) in vegetarians, P for heterogeneity=0.007; bladder cancer, RRs of 0.81 (0.36–1.81) in fish eaters and 0.47 (0.25–0.89) in vegetarians, P for heterogeneity=0.05; and cancers of the lymphatic and haematopoietic tissues, RRs of 0.85 (0.56–1.29) in fish eaters and 0.55 (0.39–0.78) in vegetarians, P for heterogeneity=0.002. Among the three main subgroups of sites contributing to the group of cancers of the lymphatic and haematopoietic tissues, the difference in incidence rates between the diet groups was non-significant for leukaemia and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and was statistically significant for multiple myeloma (P for heterogeneity=0.015); for both non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and multiple myeloma, the RRs in vegetarians (but not in fish eaters) were significant compared with those in meat eaters (RRs of 0.57 (0.35–0.95) and 0.25 (0.08–0.73), respectively). For the other cancer sites examined, there was no significant heterogeneity between the three dietary groups, but the RR for cancer of the cervix was significantly higher in vegetarians than in meat eaters (2.08 (1.05–4.12)) and the RR for prostate cancer was significantly lower in fish eaters than in meat eaters (0.57 (0.33–0.99)). The RRs for all malignant neoplasms were 0.82 (0.73–0.93) among fish eaters and 0.88 (0.81–0.96) among vegetarians (P for heterogeneity between the dietary groups=0.001).

We repeated the RR analysis after excluding the first 2 years of follow-up so as to exclude cases diagnosed shortly after recruitment to the studies. This analysis included 2933 incident cancers before age the age of 90 years. The results were very similar to those shown in Table 2. For example, the RRs for all malignant neoplasms were 0.80 (0.70–0.92) among fish eaters and 0.92 (0.84–1.01) among vegetarians (P for heterogeneity between the dietary groups=0.003), and there was significant heterogeneity of risk between the diet groups for stomach cancer, ovarian cancer and cancers of the lymphatic and haematopoietic tissues, and the RR for bladder cancer in vegetarians compared with that in meat eaters remained statistically significant (results not shown). We also repeated the analyses without adjustment for alcohol consumption, BMI, physical activity, parity and use of oral contraceptives, and the results were similar to those of the fully adjusted analyses reported in Table 2 (results not shown).

Discussion

Few prospective studies have examined cancer incidence among vegetarians. In the Adventist Health Study in California, vegetarians had a significantly lower risk for cancers of the colon and prostate than non-vegetarians, but the risk for breast cancer did not differ significantly between these dietary groups (Fraser, 1999). In Britain, the Oxford Vegetarian Study suggested no large difference in the incidence of colorectal cancer between vegetarians and non-vegetarians (Sanjoaquin et al, 2004), whereas the UK Women's Cohort Study suggested that women who did not eat any meat had a lower risk for breast cancer than did meat eaters (Taylor et al, 2007). The first results from EPIC-Oxford suggested that the incidence of breast cancer did not differ significantly between vegetarians and non-vegetarians (Travis et al, 2008), that the incidence of colorectal cancer was higher in vegetarians than in meat eaters, that the incidence of lung cancer was lower in fish eaters than in meat eaters, and that the risk for all malignant cancers was lower in fish eaters and possibly lower in vegetarians than in meat eaters (Key et al, 2009).

In this paper, we have pooled the individual participant data from the Oxford Vegetarian Study and EPIC-Oxford; hence, this includes data previously reported from these individual studies (Sanjoaquin et al, 2004; Travis et al, 2008; Key et al, 2009). The follow-up time has been extended and, whereas our previous reports included results for only five cancer sites, in this study we have reported the results for 20 cancer sites or groups of sites. The aim of this report is descriptive, and we did not have strong previous hypotheses as to which cancers might show differences in risk between the dietary groups. Therefore, these results should be interpreted cautiously, and for each significant finding we simply give a brief comment in relation to previous evidence and plausibility.

Stomach cancer risk differed significantly between the dietary groups, and was significantly lower in the vegetarians than in the meat eaters, with a similar (non-significantly) low risk among the fish eaters. This observation was based on only 49 cases of stomach cancer. Previous research has suggested that processed meat may increase the risk for stomach cancer, perhaps due to the presence of N-nitroso compounds (Forman and Burley, 2006). Therefore, it is plausible that a meat-free diet could be associated with a reduction in the risk for stomach cancer. There is also some evidence that a high intake of fruit and vegetables might reduce the risk for stomach cancer, but the data are not consistent (Forman and Burley, 2006) and, although on average vegetarians eat more fruit and vegetables than meat eaters, the difference in intake is modest (Key et al, 2009).

The risk for cancer of the cervix was significantly higher among vegetarians than among meat eaters, with a similar (non-significantly) high risk among the fish eaters. The principal cause of cervical cancer is human papillomavirus. Dietary factors have been suspected of influencing risk, but no firm conclusions have been drawn (García-Closas et al, 2005). The increased risks observed in non-meat eaters were based on only 50 cases overall and might be due to non-dietary factors, such as differences in attendance for cervical cancer screening, or to chance.

The risk for ovarian cancer differed significantly between the dietary groups, and was significantly lower among fish eaters than among meat eaters. In a review, Schulz et al (2004) concluded that high meat consumption may be associated with an increased risk of ovarian cancer. The likely mechanism for such an effect is not clear, and the differences in the risk for ovarian cancer, which we observed, could be due to chance or due to differences in reproductive factors beyond the simple categories of parity and oral contraceptive use for which we were able to adjust.

Prostate cancer risk did not differ significantly between the dietary groups, although there was a significantly lower risk among fish eaters compared with meat eaters. The role of diet in the aetiology of prostate cancer is poorly understood; there is some evidence that high intakes of dairy products might be associated with an increase in risk (Chan et al, 2005), but to explore this hypothesis further in our data we would need to examine the cancer rates among vegans, among whom there are currently too few cancers to be informative.

The risk for bladder cancer was lower among vegetarians than among meat eaters, based on 85 cancers overall. Some previous studies have suggested that certain meats, such as bacon, might increase the risk for bladder cancer, perhaps due to preformed nitrosamines (Lijinsky, 1999; Michaud et al, 2006), and this area deserves further investigation.

We observed a striking difference between the dietary groups in the risk for the group of cancers of the lymphatic and haematopoietic tissues, on the basis of 257 cancers overall. The risk for these cancers was not significantly reduced among fish eaters, but among vegetarians the risk was substantially lower than that among meat eaters. Among the three major cancer types contributing to this grouping, the risks for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and multiple myeloma, but not leukaemia, were significantly lower in vegetarians than in meat eaters. Previous research has suggested inconsistently that consumption of meat and/or exposure to live animals and raw meat among farmers and butchers might be associated with an increased risk for some of these cancers (Zhang et al, 1999; Alexander et al, 2007). Potential mechanisms could include mutagenic compounds and viruses (Cross and Lim, 2006; Alexander et al, 2007).

We did not observe any significant difference in the incidence of colorectal cancer between the dietary groups. Our earlier publications from the Oxford Vegetarian Study and EPIC-Oxford also did not report a reduction in risk for colorectal cancer among vegetarians (Sanjoaquin et al, 2004; Key et al, 2009). We also noted previously in EPIC-Oxford, that the incidence of colorectal cancer among vegetarians was identical to that in the general population of England and Wales (standardised incidence ratio 102% (95% CI: 80–129); Key et al, 2009). In the Adventist Health Study, a lower risk for colon cancer was observed among vegetarians compared with non-vegetarians (rectal cancer was not reported; Fraser, 1999). In our pooled analysis of mortality in five prospective studies, comprising the Adventist Mortality Study, the Adventist Health Study, the Health Food Shoppers Study, the Oxford Vegetarian Study and the Heidelberg Study, we observed no difference between vegetarians and non-vegetarians in mortality from colorectal cancer (Key et al, 1999). The 2007 report from the WCRF/AICR concluded that the evidence that high intakes of red and processed meat cause colorectal cancer is convincing (WCRF/AICR, 2007). In the largest single prospective study on this relationship, Cross et al (2007) reported that the risk for colorectal cancer was increased by 20% at moderate red meat intakes (equivalent to ∼86 g per day in men and ∼44 g per day in women). Meat intake among meat eaters in EPIC-Oxford was estimated as 78.1 and 69.7 g per day in men and women, respectively (Key et al, 2009), lower than intakes reported in the National Diet and Nutrition Survey for the United Kingdom, but still providing a substantial difference in intake between meat eaters and non-meat eaters. It is possible that this study did not have enough power to detect a moderate reduction in the risk for colorectal cancer among vegetarians, but our null findings on vegetarians suggest that the relationship of meat with the risk for colorectal cancer requires further research.

Total cancer incidence was significantly lower among both fish eaters and vegetarians than among meat eaters. This difference in total cancer incidence between meat eaters and non-meat eaters could not be ascribed to any one of the major cancer sites examined. We are unaware of other data comparing total cancer incidence in meat eaters and non-meat eaters, and the reason for this small difference is not known. More data are needed to further our understanding of this observation, which if confirmed is likely to be due to differences for specific cancer sites.

The results presented in this study are simply descriptive of the incidence of cancer in fish eaters and vegetarians relative to meat eaters. More detailed analyses of individual cancer sites are needed to explore, for example, whether the differences observed might be linked to particular types of meat or to other dietary or lifestyle characteristics of non-meat eaters that were not adjusted for in the current analysis.

A potential weakness of this type of study is the accuracy of the assessment of vegetarian status. The diet group was assigned on the basis of the answer to four questions, asking specifically about whether participants ever ate meat, fish, dairy products and eggs. When the diet group in EPIC-Oxford was assigned on the basis of answers to the same four questions in a follow-up questionnaire 5 years later, 85% of the vegetarians were allocated to the same diet group as at the time of recruitment (Key et al, 2009), suggesting that the assessment of vegetarian status is accurate and stable over at least several years, and may be a substantially more stable dietary characteristic than epidemiological estimates of nutrient intakes.

In conclusion, this study suggests that the incidence of all malignant neoplasms combined may be lower among both fish eaters and vegetarians than among meat eaters. The most striking finding was the relatively low risk for cancers of the lymphatic and haematopoietic tissues among vegetarians.

References

Alexander DD, Mink PJ, Adami HO, Chang ET, Cole P, Mandel JS, Trichopoulos D (2007) The non-Hodgkin lymphomas: a review of the epidemiologic literature. Int J Cancer 120 (Suppl 12): 1–39

Appleby PN, Thorogood M, Mann JI, Key TJ (1999) The Oxford Vegetarian Study: an overview. Am J Clin Nutr 70 (3 Suppl): 525S–531S

Chan JM, Gann PH, Giovannucci EL (2005) Role of diet in prostate cancer development and progression. J Clin Oncol 23: 8152–8160

Cross AJ, Lim U (2006) The role of dietary factors in the epidemiology of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma 47: 2477–2487

Cross AJ, Leitzmann MF, Gail MH, Hollenbeck AR, Schatzkin A, Sinha R (2007) A prospective study of red and processed meat intake in relation to cancer risk. PLoS Med 4: 1973–1984

Davey GK, Spencer EA, Appleby PN, Allen NE, Knox KH, Key TJ (2003) EPIC-Oxford: lifestyle characteristics and nutrient intakes in a cohort of 33 883 meat-eaters and 31 546 non meat-eaters in the UK. Public Health Nutr 6: 259–269

Forman D, Burley VJ (2006) Gastric cancer: global pattern of the disease and an overview of environmental risk factors. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 20: 633–649

Fraser GE (1999) Associations between diet and cancer, ischemic heart disease, and all-cause mortality in non-Hispanic white California Seventh-day Adventists. Am J Clin Nutr 70 (3 Suppl): 532S–538S

García-Closas R, Castellsagué X, Bosch X, González CA (2005) The role of diet and nutrition in cervical carcinogenesis: a review of recent evidence. Int J Cancer 117: 629–637

Key TJ, Fraser GE, Thorogood M, Appleby PN, Beral V, Reeves G, Burr ML, Chang-Claude J, Frentzel-Beyme R, Kuzma JW, Mann J, McPherson K (1999) Mortality in vegetarians and non-vegetarians: detailed findings from a collaborative analysis of 5 prospective studies. Am J Clin Nutr 70 (3 Suppl): 516S–524S

Key TJ, Appleby PN, Spencer EA, Travis RC, Roddam AW, Allen NE (2009) Cancer incidence in vegetarians: results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-Oxford). Am J Clin Nutr 89 (Suppl): 1620S–1626S

Lijinsky W (1999) N-nitroso compounds in the diet. Mutat Res 443: 129–138

Michaud DS, Holick CN, Giovannucci E, Stampfer MJ (2006) Meat intake and bladder cancer risk in 2 prospective cohort studies. Am J Clin Nutr 84: 1177–1183

Sanjoaquin MA, Appleby PN, Thorogood M, Mann JI, Key TJ (2004) Nutrition, lifestyle and colorectal cancer incidence: a prospective investigation of 10998 vegetarians and non-vegetarians in the United Kingdom. Br J Cancer 90: 118–121

Schulz M, Lahmann PH, Riboli E, Boeing H (2004) Dietary determinants of epithelial ovarian cancer: a review of the epidemiologic literature. Nutr Cancer 50: 120–140

Taylor EF, Burley VJ, Greenwood DC, Cade JE (2007) Meat consumption and risk of breast cancer in the UK Women's Cohort Study. Br J Cancer 96: 1139–1146

Thorogood M, Mann J, Appleby P, McPherson K (1994) Risk of death from cancer and ischaemic heart disease in meat and non-meat eaters. BMJ 308: 1667–1670

Travis RC, Allen NE, Appleby PN, Spencer EA, Roddam AW, Key TJ (2008) A prospective study of vegetarianism and isoflavone intake in relation to breast cancer risk in British women. Int J Cancer 122: 705–710

World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR) (2007) Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective. AICR: Washington DC

World Health Organization (1992) International statistical classification of deseases and related health problems-10th revision. World Health Organization: Geneva

Zhang S, Hunter DJ, Rosner BA, Colditz GA, Fuchs CS, Speizer FE, Willett WC (1999) Dietary fat and protein in relation to risk of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma among women. J Natl Cancer Inst 91: 1751–1758

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants in the Oxford Vegetarian Study and EPIC-Oxford. The Oxford Vegetarian Study and EPIC-Oxford are supported by Cancer Research UK.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Conflict of interest

TJK is a member of the Vegetarian Society. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Key, T., Appleby, P., Spencer, E. et al. Cancer incidence in British vegetarians. Br J Cancer 101, 192–197 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605098

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605098

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Spine, hip, and femoral neck bone mineral density in relation to vegetarian type and status among Taiwanese adults

Archives of Osteoporosis (2023)

-

Association of meat, vegetarian, pescatarian and fish-poultry diets with risk of 19 cancer sites and all cancer: findings from the UK Biobank prospective cohort study and meta-analysis

BMC Medicine (2022)

-

Systematic review of the impact of a plant-based diet on prostate cancer incidence and outcomes

Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases (2022)

-

Lower Compliance with Cervical Cancer Screening Guidelines Among Vegetarians in North America

Journal of Prevention (2022)

-

Association between dietary intake and risk of ovarian cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis

European Journal of Nutrition (2021)