Abstract

Using the Swedish Family-Cancer Database, the increased risk of breast cancer in women with relatives with the disease did not vary with paternal/maternal lineage. Familial breast cancer heritable component was 73% and the environmental proportion 27%. Familial aggregation of breast cancer in women below age 51 years is mainly due to heritable causes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Although having a mother or sister diagnosed with breast cancer is known to increase a woman's risk of the disease (Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer, 2001), the mechanisms underlying this association remain unclear. A family represents a group of individual sharing a common environment and genes. Hence, the mechanisms leading to this higher risk of breast cancer could be environmental, genetic, or a combination of the two.

Twin and other family studies have consistently shown a familial aggregation of female breast cancer (Lichtenstein et al, 2000; Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer, 2001; Hemminki and Granstrom, 2003; Amundadottir et al, 2004; Kerber and O'Brien, 2005; Baker et al, 2005). The familial risk of about 2.0 among first-degree relatives is so high that a substantial part of it must be caused by heritable factors (Hopper and Carlin, 1992; Lorenzo and Hemminki, 2005). One estimate suggests that heritable factors contribute to 27% of the total risk of breast cancer, and environmental factors to 73% (Lichtenstein et al, 2000). However, no corresponding studies have estimated these components in familial breast cancer. While, these proportions have mostly been measured using twin data, we use instead first- and second-degree familial relationships. As environmental sharing between second-degree relatives is probably low, the breast cancer risk associated with having affected second-degree relatives is assumed to be due to heritable causes. Breast cancers with a possible genetic cause have mainly been diagnosed at young ages (Hall et al, 1990; King et al, 1993), implying that the heritable component varies with age.

It is unknown whether breast cancer risk associated with family history differs according to the side of the family of the affected relative. Probably due to lack of reliable data, few studies have investigated this possible difference in risk (Macklin, 1959). However, such studies would clarify breast cancer inheritance pathways.

This population-based study investigated breast cancer risk among women having first- and second-degree relatives with the disease, in order to estimate the heritable and environmental components of familial breast cancer, according to women's age; risk was also examined according to paternal/maternal lineage.

Materials and methods

The Swedish Family-Cancer Database was described in detail previously (Hemminki et al, 2001). This Database was created by linking information from the national multigeneration register, censuses, cancer registries and national deaths notification using the national 10-digit personal number. Histories of cancer among mothers, sisters, grandmothers and aunts were extracted from the multigeneration register. Information on both maternal and paternal grandmothers was available for 1 550 374 women; 868 of these, born between 1952 and 1979, had been diagnosed with invasive breast cancer (with age at diagnosis of 50 years or below). Each case was matched on year of birth and geographical region to four women free of invasive and in situ breast cancer and alive at the date of the case's diagnosis. Odds ratios (ORs) for invasive breast cancer associated with having an affected relative were estimated, using conditional logistic regression. Analyses were adjusted for mother's and father's year of birth, number of maternal and paternal aunts, and number of sisters. The analyses of familial breast cancer risk associated with second-degree family history according to paternal/maternal lineage were adjusted for the above variables excluding number of sisters. Differences between ORs were evaluated using standard χ2 heterogeneity tests.

These ORs were used to estimate heritable and environmental components of familial breast cancer. Owing to low environmental sharing among second-degree relatives, the risk associated with having affected second-degree relatives was assumed to be due to heritable causes. Hence, assuming a 50% gene sharing between first- and second-degree relatives, we concluded that the excess risk associated with first-degree family history should be equal to twice the excess risk associated with second-degree family history. This excess risk was considered as being due to heritable causes. If it was lower than the excess risk evaluated through conditional logistic regression, the difference was assumed to be due to environmental causes.

Results

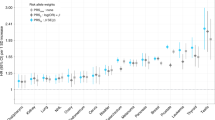

Women with a first- and second-degree relative with breast cancer had a higher risk of contracting the disease than women without such a family history (Figure 1). This risk was higher when the affected relative is a mother and/or a sister(s) compared to a grandmother and/or an aunt(s). In women of all ages, the ORs for breast cancer associated with first- and second-degree family history were 2.86 (95% CI: 2.15–3.82) and 1.68 (1.38–2.03), respectively. Those risks were higher when women were of a younger age. Breast cancer risk did not vary with paternal/maternal lineage, the OR being 1.64 (1.25–2.14) and 1.68 (1.30–2.17) when the affected relative was on the mother's and father's side of the family, respectively (Figure 1).

Considering the breast cancer risk associated with having an affected second-degree relative as a correct estimate of familial breast cancer risk due to heritable causes, heritable and environmental components of breast cancer were estimated using the ORs presented in Figure 1 (see Table 1). Considering all women, familial breast cancers were 73% heritable and 26% environmental. The heritable component was 96 and 66% in women aged less than 40 and 40–50 years, respectively.

Discussion

Women with first- and second-degree relatives with breast cancer have a higher risk of the disease themselves. This risk is higher when the affected relative was a mother or a sister(s) compared to a grandmother or an aunt(s), as found in a meta-analysis of 74 studies (Pharoah et al, 1997). Family history of breast cancer was extracted from national registries and did not rely on reporting of affected relatives as in most studies. The quality of reporting was found to worsen with increasingly distant relatives (Ziogas and Anton-Culver, 2003), indicating possible unreliability of the data in such studies.

Few studies have investigated whether breast cancer risk varies according to paternal/maternal lineage (Macklin, 1959). In the present study, the risk of breast cancer associated with having affected second-degree relatives did not vary according to paternal/maternal lineage, which is consistent with the failure to identify sex-linked genes in breast cancer.

This report uses a novel method to estimate heritable and environmental components of a disease. Although these proportions have mostly been measured using twin data, we used first- and second-degree family history. Overall, familial breast cancer was found to be 73% heritable and 26% environmental, suggesting that familial aggregation in young breast cancers is mainly due to heritable factors. Previous studies have found similar results (Hopper and Carlin, 1992; Hemminki and Granstrom, 2003). The heritable component of familial breast cancers increased with decreasing women's age, with 96 and 66% of familial breast cancers in women aged below 40 and 40–50 years, respectively. Factors explaining breast cancer familial aggregation might differ according to age. Participants included in the present report were born between 1952 and 1979, with age at diagnosis ranging between 16 and 50 years old, and different estimates of heritable and environmental components of familial breast cancer might be observed in older cases.

The Swedish Family-Cancer Database includes information on most of the Swedish population, providing results, which are generalisable to a population of a similar age to the one discussed. The results presented here suggest that familial aggregation in young breast cancers is mainly due to heritable causes.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Amundadottir LT, Thorvaldsson S, Gudbjartsson DF, Sulem P, Kristjansson K, Arnason S, Gulcher JR, Bjornsson J, Kong A, Thorsteinsdottir U, Stefansson K (2004) Cancer as a complex phenotype: pattern of cancer distribution within and beyond the nuclear family. PLoS Med 1: e65

Baker SG, Lichtenstein P, Kaprio J, Holm N (2005) Genetic susceptibility to prostate, breast, and colorectal cancer among Nordic twins. Biometrics 61: 55–63

Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer (2001) Familial breast cancer: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 52 epidemiological studies including 58,209 women with breast cancer and 101,986 women without the disease. Lancet 358: 1389–1399

Hall JM, Lee MK, Newman B, Morrow JE, Anderson LA, Huey B, King MC (1990) Linkage of early-onset familial breast cancer to chromosome 17q21. Science 250: 1684–1689

Hemminki K, Granstrom C (2003) Familial breast cancer: scope for more susceptibility genes? Breast Cancer Res Treat 82: 17–22

Hemminki K, Li X, Plna K, Granstrom C, Vaittinen P (2001) The nation-wide Swedish family-cancer database – updated structure and familial rates. Acta Oncol 40: 772–777

Hopper JL, Carlin JB (1992) Familial aggregation of a disease consequent upon correlation between relatives in a risk factor measured on a continuous scale. Am J Epidemiol 136: 1138–1147

Kerber RA, O'Brien E (2005) A cohort study of cancer risk in relation to family histories of cancer in the Utah population database. Cancer 103: 1906–1915

King MC, Rowell S, Love SM (1993) Inherited breast and ovarian cancer. What are the risks? What are the choices? JAMA 269: 1975–1980

Lichtenstein P, Holm NV, Verkasalo PK, Iliadou A, Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M, Pukkala E, Skytthe A, Hemminki K (2000) Environmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer – analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. N Engl J Med 343: 78–85

Lorenzo BJ, Hemminki K (2005) Familial lung cancer and aggregation of smoking habits: a simulation of the effect of shared environmental factors on the familial risk of cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 14: 1738–1740

Macklin MT (1959) Comparison of the number of breast-cancer deaths observed in relatives of breast-cancer patients, and the number expected on the basis of mortality rates. J Natl Cancer Inst 22: 927–951

Pharoah PD, Day NE, Duffy S, Easton DF, Ponder BA (1997) Family history and the risk of breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 71: 800–809

Ziogas A, Anton-Culver H (2003) Validation of family history data in cancer family registries. Am J Prev Med 24: 190–198

Acknowledgements

The Family-Cancer Database was created by linking registries maintained by Statistics Sweden and the Swedish Cancer Register, and supported by the Deutsche Krebshilfe, the Swedish Cancer Society, the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research and the EU, LSHC-LT-2004-503465. EC is funded by a Marie Curie Intra-European fellowship from the European community's Sixth Framework Programme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Couto, E., Hemminki, K. Estimates of heritable and environmental components of familial breast cancer using family history information. Br J Cancer 96, 1740–1742 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603753

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603753

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Increased risk of contralateral breast cancer for BRCA1/2 wild-type, high-risk Korean breast cancer patients: a retrospective cohort study

Breast Cancer Research (2024)

-

The Impact of microRNA SNPs on Breast Cancer: Potential Biomarkers for Disease Detection

Molecular Biotechnology (2024)

-

Association of the BRCA1 promoter polymorphism rs11655505 with the risk of familial breast and/or ovarian cancer

Familial Cancer (2013)

-

Risk of breast cancer in families of multiple affected women and men

Breast Cancer Research and Treatment (2012)

-

Bias in the Reporting of Family History: Implications for Clinical Care

Journal of Genetic Counseling (2012)