Abstract

In a follow-up of 1 208 001 women aged 20–74 years, no significant association was found between twin births (112 cases) and risk, though those with twin girls had a non-significantly higher risk than those with singleton births; among the latter, those with girls only had a higher risk of endometrioid tumours (incidence rate ratio 1.35; 95% confidence interval 1.03–1.76, based on 475 cases) than women with boys only.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The protective effect of pregnancies on the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer is usually explained by their influence on lifetime number of ovulations (Risch, 1998). Women prone to have multiple births have a higher level of follicle-stimulating hormone (Bulmer, 1970; Corney et al, 1981; Risch, 1998) and may also ovulate more often (Allen, 1981), possibly leading to an increased risk (Risch, 1998; Lukanova and Kaaks, 2005). Certain maternal or pregnancy-related factors associated with twinning may however be related to a reduced risk (Risch, 1998) though only a slightly lower or similar risk has been reported in twin compared to singleton mothers (Wyshak et al, 1983; Olsen and Storm, 1998; Lambe et al, 1999; Whiteman et al, 2000; Titus-Ernstoff et al, 2001; Neale et al, 2004, 2005).

Hormones may play a role in ovarian cancer carcinogenesis (Riman et al, 1998; Risch, 1998; Lukanova and Kaaks, 2005). Maternal hormone levels have been found to be higher in pregnancies involving twins (TambyRaya and Ratnam, 1981; Risch, 1998; Storgaard et al, 2006). The levels of oestrogens, androgens and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) seem to differ by sex of the fetus in singleton gestations (Robinson et al, 1977; Forest et al, 1980; Haning et al, 1989; Cerhan et al, 2000; Luke et al, 2005). A different risk pattern according to sex of children may therefore throw light on alternative hormone-related hypotheses, but few studies have focused on this issue.

We have examined associations between twin births, sex of children and the risk of ovarian cancer in a large cohort of parous Norwegian women.

Materials and methods

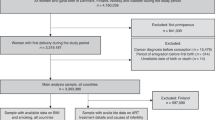

The present study includes Norwegian women born in the period 1925-1979, as recorded in the national population register. The study population comprised 1 208 001 parous women, contributing a total of 27 634 403 person-years at risk in the age interval 20–74 years during follow-up until 1st January, 2000. The mean follow-up time was 22.9 years, range 1 month–45 years. A total of 28 911 women had experienced a twin birth; 354 of these had two twin births and five had three. Women with higher plurality of a multiple birth (n=461) were excluded. Information on reproductive history (date of birth for each live born child) and cancer diagnoses was assessed through national registers.

A total of 5606 women were diagnosed with ovarian cancer (ICD 7th Revision, code 175). Of these, 5204 (92.8%) were classified as invasive epithelial ovarian cancer, 291 (5.2%) as non-epithelial ovarian cancer, whereas 111 (2.0%) had no valid histological code. Borderline tumours were not considered. Separate analyses were performed for epithelial and non-epithelial ovarian cancer, and by histological subtype (Table 1). A woman was withdrawn from the risk set at date of diagnosis of any type of ovarian cancer.

Statistical analysis

A log-linear Poisson regression model of person–years at risk (Breslow and Day, 1987) was applied. Attained age was considered as timescale (categorical variable, 1-year intervals). The variables representing parity (number of full term births) and different birth characteristics were treated as time-dependent categorical variables. A twin birth was identified through identical birth dates of siblings. Birth-cohort, maternal age at first and last (most recent) childbirth, were all considered as categorical variables in 5-year intervals.

Tabulation of individual records into person–years tables and Poisson regression analyses of person–years at risk, with calculation of maximum likelihood estimates of incidence rate ratios (IRR) and likelihood ratio tests were performed by means of the EPICURE programme package (Preston et al, 1996).

Results

No significant association was found between twin births and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer (112 cases), but women with twin girls had a slightly higher risk than women with singletons only, whereas women with twin boys or twins of both sexes, had a slightly lower risk (Table 2). The elevated risk associated with twin girls was more pronounced before age 45 years, but the interaction test did not reach statistical significance (Table 2).

The association with sex of twins reached statistical significance for mucinous tumours (P=0.019, test for heterogeneity); women with twin girls had almost twice the risk of singleton mothers (IRR=1.67, 95% confidence interval (CI)=0.98–2.91, 13 of 20 cases), whereas with twin boys the risk was lower (IRR=0.26, 95% CI=0.07–1.04; two cases only). An adverse effect of twin girls was also seen for serous tumours before age 45 years (IRR=2.08, 95% CI=1.15–3.77 and IRR=0.72, 95% CI=0.40–1.29 in women below and above age 45 years, respectively; P=0.10, test for interaction). Twin mothers had a slightly reduced risk of endometrioid tumours (IRR=0.52, 95% CI=0.23–1.16); numbers were too low to discriminate by sex of the twins (Table 1). Twin mothers had a higher risk of non-epithelial ovarian cancer (IRR=1.79, 95% CI=0.98–3.28), especially stromal tumours (IRR=3.97, 95% CI=2.00–7.86).

In women with singleton births, no association was found between sex of children and the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer (Table 2). However, women with girls only had significantly higher risk of endometrioid tumours than women with boys only (IRR=1.35, 95% CI=1.03–1.76), whereas women with both girls and boys had a rather similar risk (IRR=1.16, 95% CI=0.88–1.52). The adverse effect of having girls only was more pronounced in women with at least three children (IRR values of 1.34, 1.28 and 1.61 in women with one, two and ⩾three children, respectively), and in women above age 45 years (IRR values of 1.23 and 1.40 in women below and above age 45 years, respectively). No consistent association was seen between sex of children and other histological subtypes (results not shown).

Discussion

This large cohort study did not show any overall association between twin births and the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer, but women with twin girls seemed to have a higher risk than singleton mothers. The increased risk was particularly pronounced for mucinous tumours, and serous tumours before age 45 years; a slightly lower risk was seen at older ages. Sex of children in singleton births was associated with the risk of endometrioid tumours only; women with girls only had the highest risk.

Previous studies have found a lower or rather similar risk of epithelial ovarian cancer in twin compared to singleton mothers (Olsen and Storm, 1998; Lambe et al, 1999; Whiteman et al, 2000; Titus-Ernstoff et al, 2001; Neale et al, 2004, 2005), but few have focused on sex of the twins, or performed subgroup analyses. One study based on pooled data from eight case–control studies (Whiteman et al, 2000) found an adverse effect of twinning in relation to mucinous tumours, but a protective effect in relation to non-mucinous tumours. However, no information was given on the sex of the twins. Another study (Lambe et al, 1999) found a more pronounced reduction in risk in mothers with twins of opposite sex than same-sex twins; no histology-specific results were presented.

Consistent with our finding for endometrioid tumours, one previous study (Gierach et al, 2006) found that women with girls only had higher risk of epithelial ovarian cancer than women with boys only, or boys and girls. In another study (Olsen and Storm, 1998), the sex ratio among newborns to mothers who later developed ovarian cancer was similar to that in infants with mothers without such a diagnosis.

There is growing evidence that oestrogens play a role in ovarian cancer carcinogenesis, as well as tumour progression (Mink et al, 2002; Cunat et al, 2004; Riman et al, 2004). The hCG level is higher during female than male gestations (Robinson et al, 1977; Haning et al, 1989; Cerhan et al, 2000; Luke et al, 2005) and hCG is involved in oestrogen production during pregnancy (Risch, 1998). Moreover, the hCG level has been found to be higher in twin than in singleton pregnancies (Haning et al, 1989; Luke et al, 2005), and highest when both twins are girls (Steier et al, 1989). A potential increased risk of mucinous and serous tumours in women with twin girls, and an increased risk of endometrioid tumours in women with girls only, may thus be related to an adverse effect of oestrogens, acting either at early or later stages of carcinogenesis during pregnancy. Oestrogen receptors have been found both in endometrioid, serous and mucinous ovarian tumours (Risch, 1998; Gadducci et al, 2004; Auranen et al, 2005; Lee et al, 2005), and also in normal ovarian surface epithelial cells (Cunat et al, 2004; Auranen et al, 2005). The apparent reduced risk of endometrioid tumours in twin mothers, however, is more likely explained by other, possibly maternal factors (Risch, 1998).

In summary, the present results suggest a complex relationship between twin births, sex of children and ovarian cancer risk, including a heterogeneity according to woman's age, as well as histological subtype. Women with twin girls or women with daughters only, seem to have an increased risk of certain histological types, whereas pregnancies involving a male foetus showed either no association, or a reduced risk. Maternal, as well as pregnancy-related factors, may explain these epidemiological findings. Further studies are needed to exclude the role of chance.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Allen G (1981) The twinning and fertility paradox. Prog Clin Biol Res 69A: 1–13

Auranen A, Hietanen S, Salmi T, Grénman S (2005) Hormonal treatments and epithelial ovarian cancer risk. Int J Gynecol Cancer 15: 692–700

Breslow NE, Day NE (1987) Statistical Methods in Cancer Research, Vol. 2. The Design and Analysis of Cohort Studies. IARC Scientific Publications No. 82: Lyon

Bulmer MG (1970) The Biology of Twinning in Man. Oxford University Press: London

Cerhan JR, Kushi LH, Olson JE, Rich SS, Zheng W, Folsom AR, Sellers TA (2000) Twinship and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 92: 261–265

Corney G, Seedburg D, Thompson B, Campbell DM, MacGillivray I, Timlin D (1981) Multiple and singleton pregnancy: differences between mothers as well as offspring. Prog Clin Biol Res 69A: 107–114

Cunat S, Hoffmann P, Pujol P (2004) Estrogens and epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 94: 25–32

Forest MG, de Peretti E, Lecoq A, Cadillon E, Zabot MT, Thoulon JM (1980) Concentration of 14 steroid hormones in human amniotic fluid of midpregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 51: 816–822

Gadducci A, Cosio S, Gargini A, Genazzani AR (2004) Sex-steroid hormones, gonadotropin and ovarian carcinogenesis: a review of epidemiological and experimental data. Gynecol Endocrinol 19: 216–228

Gierach GL, Modugno F, Ness RB (2006) Gender of offspring and maternal ovarian cancer risk. Gynecol Oncol 101: 476–480

Haning Jr RV, Curet LB, Poole WK, Boehnlein LM, Kuzma DL, Meier SM (1989) Effects of fetal sex and dexamethasone on preterm maternal serum concentrations of human chorionic gonadotropin, progesterone, estrone, estradiol, and estriol. Am J Obstet Gynecol 161: 1549–1553

Lambe M, Wuu J, Rossing M-A, Hsieh C-C (1999) Twinning and maternal risk of ovarian cancer. Lancet 353: 1941

Lee P, Rosen DG, Zhu C, Silva EG, Liu J (2005) Expression of progesterone receptor is a favourable prognostic marker in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 96: 671–677

Lukanova A, Kaaks R (2005) Endogenous hormones and ovarian cancer: epidemiology and current hypotheses. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 14: 98–107

Luke B, Hediger M, Min S-J, Brown MB, Misiunas RB, Gonzalez-Quintero VH, Nugent C, Witter FR, Newman RB, Hankins GD, Grainger DA, Macones GA (2005) Gender mix in twins and fetal growth, length of gestation and adult cancer risk. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 19 (Suppl 1): 41–47

Mink PJ, Sherman ME, Devesa SS (2002) Incidence patterns of invasive and borderline ovarian tumors among white women and black women in the United States. Results from the SEER program, 1978–1998. Cancer 95: 2380–2389

Neale RE, Darlington S, Murphy MFG, Silcocks PBS, Purdie DM, Talbäck M (2005) The effects of twins, parity and age at first birth on cancer risk in Swedish women. Twin Res Hum Genet 8: 156–162

Neale RE, Purdie DM, Murphy MFG, Mineau GP, Bishop T, Whiteman DC (2004) Twinning and the incidence of breast and gynecological cancers (United States). Cancer Causes Control 15: 829–835

Olsen J, Storm H (1998) Pregnancy experience in women who later developed oestrogen-related cancers (Denmark). Cancer Causes Control 9: 653–657

Preston DL, Lubin JH, Pierce DA, McConney ME (1996) EPICURE – Programs for Generalized Risk Modeling and Person-year Computation. Seattle: Hirosoft International Corporation

Riman T, Nilsson S, Persson I (2004) Review of epidemiological evidence for reproductive and hormonal factors in relation to the risk of epithelial ovarian malignancies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 83: 783–795

Riman T, Persson I, Nilsson S (1998) Hormonal aspects of epithelial ovarian cancer: review of epidemiological evidence. Clin Endocrinol 49: 695–707

Risch HA (1998) Hormonal etiology of epithelial ovarian cancer, with a hypothesis concerning the role of androgens and progesterone. J Natl Cancer Inst 90: 1774–1786

Robinson JD, Judd HL, Young PE, Jones OW, Yen SS (1977) Amniotic fluid androgens and estrogens in midgestation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 45: 755–761

Steier JA, Myking OL, Ulstein M (1989) Human chorionic gonadotropin in cord blood and peripheral maternal blood in singleton and twin pregnancies at delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 68: 689–692

Storgaard L, Bonde JP, Olsen J (2006) Male reproductive disorders in humans and prenatal indicators of estrogen exposure. A review of published epidemiological studies. Reprod Toxicol 21: 4–15

TambyRaya RL, Ratnam SS (1981) Plasma steroid changes in twin pregnancies. Prog Clin Biol Res 69A: 189–195

Titus-Ernstoff L, Perez K, Cramer DW, Harlow BL, Baron JA, Greenberg ER (2001) Menstrual and reproductive factors in relation to ovarian cancer risk. Br J Cancer 84: 714–721

Whiteman DC, Murphy MFG, Cook LS, Cramer DW, Hartge P, Marchbanks PA, Nasca PC, Ness RB, Purdie DM, Risch HA (2000) Multiple births and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 92: 1172–1177

Wyshak G, Honeyman MS, Flannery JT, Beck AS (1983) Cancer in mothers of dizygotic twins. J Natl Cancer Inst 70: 593–599

Acknowledgements

Ms Gry Baadstrand Skare, medical laboratory technologist at the Cancer Registry of Norway, has given valuable advice on the categorisation of histopathological type. The study was supported by the Norwegian Cancer Society through a full-time research position for Dr Albrektsen.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Albrektsen, G., Heuch, I., Thoresen, S. et al. Twin births, sex of children and maternal risk of ovarian cancer: a cohort study in Norway. Br J Cancer 96, 1433–1435 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603687

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603687

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Offspring sex and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer: a multinational pooled analysis of 12 case–control studies

European Journal of Epidemiology (2020)