Abstract

Two recent North American studies have shown that completion of 5-fluorouracil (5FU)-based adjuvant chemotherapy is a major prognostic factor for the survival of elderly stage III colon cancer patients. The aim of the present study was to confirm this finding in a population-based series from Australia. The study cohort comprised 851 stage III colon cancer patients treated by surgery alone and 461 who initiated the Mayo chemotherapy regime. One-third of patients who initiated chemotherapy failed to complete more than three cycles of treatment. Independent predictors for failure to complete were treatment in district or rural hospitals, low socioeconomic index and treatment by a low-volume surgeon. Patients who failed to complete chemotherapy showed worse cancer-specific survival compared not only to those who completed treatment (HR=2.24; 95% confidence interval (CI) (1.66–3.03), P<0.001) but also to those treated by surgery alone (HR=1.37; 95% CI (1.09–1.72), P=0.008). The current and previous studies demonstrate the importance of completing adjuvant 5-FU-based chemotherapy for colon cancer. Further prospective studies are required to identify better the physiological and socioeconomic factors responsible for failure to complete chemotherapy so that appropriate improvements in health service delivery can be made.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Randomised controlled trials conducted in the 1980s demonstrated that 5-fluorouracil (5FU)-based chemotherapy resulted in a 10% absolute improvement in 5-year survival for stage III CRC patients (Moertel et al, 1990). As a result of these trials the National Institutes of Health recommended in 1990 the routine administration of FU-based adjuvant chemotherapy for medically fit patients with completely resected stage III CRC (NIH Consensus Conference, 1990). In the early 1990s, adjuvant chemotherapy with 5FU was used in combination with levamisole or leucovorin and regimes varied from 6 to 12 months in length. By 1995, the standard of care in many countries, including Australia, had become the Mayo regime of intravenous 5FU/leucovorin for 6 months.

Randomised controlled clinical trials generally analyse the benefits of treatment in patient cohorts with few comorbidities. Participants in the earlier randomised clinical trials for CRC were highly selected and most patients were aged <70 years. These do not accurately represent all patients who may ultimately become candidates for treatment in the general population. Nevertheless, several reports have recently documented a similar degree of survival benefit from 5FU in older patient groups from a population-based setting (Iwashyna and Lamont, 2002; Sundararajan et al, 2002; Jessup et al, 2005; Dobie et al, 2006; Neugut et al, 2006). These results support earlier evidence from randomised control trials and clearly establish benefit from 5FU-based adjuvant chemotherapy in stage III colon cancer.

Two recently published studies using the SEER database examined the early termination of adjuvant chemotherapy regimes in the elderly population in relation to survival (Dobie et al, 2006; Neugut et al, 2006). These papers reported that patients who failed to complete 5FU-based chemotherapy showed significantly worse survival compared to those who completed the treatment. Confirmation of the findings with respect to completion of treatment has important implications for the delivery of effective healthcare to patients with colon cancer. This paper examines the effect on survival of failure to complete adjuvant chemotherapy in a population-based cohort that includes patients of all ages and who were treated exclusively with the Mayo regime.

Methods

Study population

Pathology records from the four major hospitals in Western Australia were used to identify patients diagnosed with CRC during the period 1994–2001 inclusive. The pathology services at these hospitals also process specimens from minor district and country hospitals. This patient list was crosschecked with the Cancer Registry of Western Australia. Approximately 90% of all CRC patients who underwent surgical resection were identified for the population of Western Australia, comprising 1.8–2 million people over the study period. Tumour stage was classified according to the current American Joint Committee on Cancer guidelines (AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 6th edn, 2002). A total of 2024 patients with CRC fulfilled the criteria for stage III CRC and 1404 of these had colonic carcinoma. All cases showed clear margins (R0 resections). Rectal carcinomas were defined as originating within 12 cm of the anal verge and these were excluded from the analysis. Information on pathological variables was obtained from the histopathology reports. Perforation was considered to be present if noted by the surgeon at operation or on histopathological review of the specimen. Clinical records were used to classify tumours presenting with obstruction. Anatomical site of the tumour was crosschecked with information from admission and procedure records. Colonic cancers were subclassified as being proximal or distal to, and including, the splenic flexure.

Surgical caseload was defined as low (⩽10), medium (11–50) and high (>50) for stage II and III colon cancer resections over the 8-year study period. Hospitals were classified as teaching (university affiliated), private (fee for service), district (non-teaching and non-private institutions located in the metropolitan region of Perth) or rural (non-metropolitan). Each patient's post code address was obtained from the West Australian Cancer Registry database and this was linked to Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (advantaged/disadvantaged and economic resources) obtained from the 2001 Australian census (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2001). Patients with an advantaged/disadvantaged score of 1 were the most deprived quintile in socioeconomic terms, whereas a score of 5 corresponds to the most advantaged group. Patients with a score of 1 for economic resources had the least financial resources, whereas those with a score of 5 had the most. Ethics approval for the project was obtained from individual hospital Human Research Ethics Committees, the University of Western Australia and the Confidentiality of Health Information Committee.

Adjuvant chemotherapy

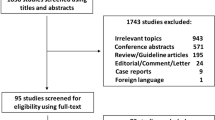

Procedure codes from the morbidity database of the Data Linkage Unit, Health Department of Western Australia, were used to identify patients who began chemotherapy within 120 days of resection. The adjuvant chemotherapy regimes used in Western Australia varied during the study period. Cases were individually reviewed using hospital records and only those patients (n=461) who received the Mayo regime were included in the study. A total of 92 patients who received the Roswell or other regimes were excluded. Patients who received chemotherapy for a recurrence were also documented (n=150). Less than 15 doses administered were defined as ⩽3 cycles (n=156) and 16–30 doses as 4–6 cycles (n=305). Therefore, the study cohort (n=1312) comprised 851 patients treated by surgery alone and 461 who initiated the Mayo chemotherapy regime.

Survival data

Mortality data were obtained from the Death Registry of the Health Department of Western Australia. Death reports were reviewed individually and classified as death due to colon cancer or from other causes. The perioperative mortality rate (4.8%) was defined as death within 30 days of surgery. At the end of the study period, 155 (11.8%) patients died from unrelated causes and 657 (50.1%) from recurrence of colonic cancer. Of the 461 patients who initiated adjuvant chemotherapy, three patients died as a result of chemotherapy treatment (0.65%). Sepsis and pancytopaenia were responsible for two deaths and one patient died of gastrointestinal haemorrhage secondary to a duodenal ulceration. One other patient died from a cerebrovascular accident while on chemotherapy 3 months after resection. Survival time was calculated from the date of diagnosis to date of death from cancer or 1 March 2006, whichever came first. This enabled cancer-specific and overall survival to be evaluated. The mean length of follow-up was 52 months and the median was 36 months (range 0–147 months).

Statistical analysis

Chi square analysis was used to identify factors influencing the rates of chemotherapy initiation and completion. A multiple logistic regression model in which each demographic, pathological and clinical variable listed in Table 1 was adjusted for all others was used to estimate odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for independent predictors of chemotherapy initiation or completion. Survival analysis was conducted using both unadjusted Kaplan–Meier analysis and Cox proportional hazards regression. The log-rank test was used to determine the significance for Kaplan–Meier analysis. A Cox proportional hazards regression model was developed for survival in which each variable was adjusted for all others. Statistical significance was deemed if P<0.05.

Results

In this population-based cohort, just over one-third of stage III colon cancer patients initiated chemotherapy using the Mayo regime (Tables 1 and 2). From 1997 to 2001, the rate remained steady at approximately 40% of cases. This is probably reflective of stabilisation of surgical referral and oncological practice following the initial period of 5FU chemotherapy implementation. As expected, chemotherapy use declined with increasing age. Patients treated in private hospitals and those whose tumours were detected by colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy were more likely to initiate chemotherapy. These same three factors were found in multivariate analysis to be independent predictors for the initiation of chemotherapy (Figure 1). None of the pathological variables were associated with the commencement of chemotherapy.

The survival of patients who initiated chemotherapy is shown in Table 3 according to the number of cycles received. Compared to patients treated by surgery alone, those who received only one cycle of chemotherapy showed significantly worse survival. A trend for worse survival was also observed for patients treated with two or three cycles. In contrast, patients treated with four, five or six cycles showed better survival than those treated by surgery alone. On the basis of these results and for this study, patients who received 4–6 cycles were classified as having completed chemotherapy, whereas those treated with 1–3 cycles were deemed not to have completed this treatment. The former group was estimated to have a 30% survival advantage and the latter group a 40% survival disadvantage compared to patients treated by surgery alone (Table 3 and Figure 2).

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis for stage III colon cancer patients treated with surgery alone (0 cycles, light grey), 1–3 cycles (incomplete chemotherapy, dark grey) or 4–6 cycles (complete chemotherapy, black) of 5FU adjuvant chemotherapy using the Mayo regime. Log-rank test: P=0.021 for incomplete chemotherapy vs surgery alone P<0.0001 for complete chemotherapy vs surgery alone; P<0.0001 for complete chemotherapy vs incomplete chemotherapy.

Two-thirds of patients who initiated chemotherapy completed 4–6 cycles of treatment (Tables 4 and 5). Factors associated with higher rates of completion were N1 nodal status, high surgeon caseload, treatment in teaching and private hospitals and high socioeconomic indices. Multivariate analysis revealed that independent predictors for completion of chemotherapy were the type of treatment hospital, high socioeconomic index and high surgical volume (Table 6). Females showed a trend for less likelihood of completion (P=0.08).

Discussion

Two recent studies using SEER data reported that stage III colon cancer patients who failed to complete 5FU chemotherapy showed worse survival compared to those who completed the regimen (Dobie et al, 2006; Neugut et al, 2006). The present investigation of an Australian population-based cohort of stage III colon cancer confirms the findings of the North American groups. Moreover, the current study also found that patients who initiated but did not complete chemotherapy (1–3 cycles received) showed significantly worse survival than patients treated by surgery alone (Table 3).

There were several differences in study design between the current investigation and the North American reports. Patients of all ages were included here, whereas only >65-year-old patients were investigated previously. Despite the younger cohort, only 35% of patients initiated chemotherapy (Tables 1 and 2) compared to 54 and 55% for the SEER-derived cohorts (Dobie et al, 2006; Neugut et al, 2006). The completion rate for patients who initiated chemotherapy in the present investigation (66%,Tables 4 and 5) was comparable to the North American report (64%) from the same study period (Neugut et al, 2006). Both were slightly lower than the second North American report (78%), which investigated an earlier study period, included both 12 and 6 month regimes and presented 3-year cancer-specific mortality data (Dobie et al, 2006). Although the present study had a smaller sample size, individual patient records were reviewed for pathology, chemotherapy regime and cause of death.

In spite of these minor differences in study design, all three investigations have observed a significant survival advantage associated with the completion of chemotherapy. The survival advantage was estimated at 33% (Table 3) and 21% (Dobie et al, 2006) compared to patients treated by surgery alone. When patients who did not complete chemotherapy were used as the reference group, the survival advantage was even greater at 47% (Neugut et al, 2006) and 55% in the current investigation (HR=0.45; 95% CI (0.33–0.60), P=0.005). Importantly, the same pattern of survival advantage from the completion of chemotherapy was also observed by our group in a population-based cohort of stage II colon cancer patients (unpublished). Using patients treated by surgery alone as the reference group (n=1362), patients who completed chemotherapy (n=142) showed a significant survival advantage (HR=0.63; 95% CI (0.41–0.96), P=0.03), whereas those who did not complete (n=49) showed worse survival (HR=1.27; 95% CI (0.71–2.29), P=0.42).

The predictors for initiation of chemotherapy were found in multivariate analysis to be younger patient age, treatment in a private hospital and preoperative colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy (Figure 1). The first two factors are likely to reflect patients with lower comorbidities and higher socioeconomic status, respectively, whereas the third factor may represent non-emergency presentation. Interestingly, none of the reported pathological variables was predictive for the initiation of chemotherapy in stage III colon cancer. District hospitals were defined here as non-teaching and non-private institutions located in the metropolitan region of Perth. Patients treated in these hospitals showed a two-fold lower initiation rate for chemotherapy compared to teaching institutions, suggesting deficiencies in access to oncology services.

Patients with greater levels of psychosocial support and financial resources would be expected to show higher rates of chemotherapy completion. This is supported by our findings that patients with a high socioeconomic index or who were treated in teaching or private hospitals showed higher rates of completion (Table 6). Previous North American studies have shown that married status is also predictive for the completion of chemotherapy (Dobie et al, 2006; Neugut et al, 2006). It is of concern that patients treated in district and rural hospitals showed approximately half the rate of chemotherapy completion compared to patients from teaching and private hospitals (Table 6). There is clearly a need to identify the underlying reasons leading to low initiation and completion rates for the 25% of colon cancer patients treated in these centres so that equality of health provision can be improved.

There are several current and commonly used 5FU regimes ranging from protracted, continuous infusional 5FU delivery to bolus schedules. Protracted infusional regimes were developed to maximise 5FU dose intensity. They have been found to be as effective as the bolus regimens and less toxic, with less impact on quality of life (Andre et al, 2003; Saini et al, 2003; Goyle and Maraveyas, 2005). The Mayo and Roswell Park regimes are commonly used in the USA and have different safety profiles. The Mayo regime demonstrates more haematological but less gastrointestinal toxicity compared with the Roswell Park regime. In the UK and Europe the Lokich, LV5FU2 (de Gramont) or QUASAR-type regimens are commonly used and have advantages in terms of toxicity when compared with the Mayo regime, but comparable survival rates (Goyle and Maraveyas, 2005).

The other major factor likely to result in failure to complete chemotherapy is toxicity. It is well-documented that bolus schedules of 5FU cause more severe leucopenia and stomatitis in elderly patients, particularly in females (Milano et al, 1992; Meta-analysis Group in Cancer, 1998; Zalcberg et al, 1998; Popescu et al, 1999; Tebbutt et al, 2000; Sloan et al, 2002; Chansky et al, 2005). In agreement with these findings, the present study found that females were less likely to complete adjuvant chemotherapy when adjusted for other variables (Table 6), and we postulate this is due to an increased incidence of toxicity. The retrospective nature of this population-based study meant that information on treatment-related toxicity was not available. The skill and experience of the administrators of chemotherapy in the management of toxicities and the capacity to provide psychosocial support to patients may impact on the likelihood of a patient to complete their chemotherapy regime.

Many of the toxicities that lead to the termination of 5FU chemotherapy culminate around the time of the third cycle (Tebbutt et al, 2000). Unfortunately, steady-state plasma 5FU levels do not correlate with toxicity (Jodrell et al, 2001) and hence pharmacokinetic monitoring is not used to identify patients who are at increased risk of toxicity (Tebbutt et al, 2000). In randomised controlled trials, dose reductions are common after the first two cycles and 15–30% of patients fail to complete chemotherapy (Wolmark et al, 1993; O'Connell et al, 1997; Poplin et al, 2005). The relationship between systemic exposure and treatment efficacy has not been demonstrated, however, and can only be ascertained by conducting prospective randomised studies that compare a targeted dose adjustment to a fixed dose (Milano et al, 1994).

A novel and unexpected observation from this study was that stage III colon cancer patients who failed to complete chemotherapy showed significantly worse cancer-specific survival compared to patients treated by surgery alone (Table 3 and Figure 2). Dobie et al (2006) did not find a significant difference in survival between these two patient groups using 3-year cancer mortality data and Neugut et al (2006) did not report this comparison. It is unlikely that 5FU toxicity accounts for the increased mortality observed here as recent trials have reported a chemotherapy-related death rate of only 0.5% (Andre et al, 2004). The chemotherapy-related death rate in this population-based cohort of stage III colon cancer was 0.65% (3 out of 461). The 60-day mortality for patients that initiated adjuvant chemotherapy was 0.4%. This is comparable to published benchmark data for the safety of adjuvant chemotherapy in colon cancer (Katopodis et al, 2004).

One possible explanation is that failure to complete chemotherapy is indicative of high toxicity and this may in turn be associated with a more aggressive tumour phenotype or impairment of the host immune response. The CpG island methylator phenotype has worse prognosis (Van Rijnsoever et al, 2003; Ward et al, 2003) and is linked to the folate pathway (Kawakami et al, 2003). This latter pathway has been implicated in toxicity to 5FU (Pinedo and Peters, 1988).

The results of the current study have relevance for the introduction of new therapies for colon cancer. Oral fluoropyrimidines (UFT and capecitabine) mimic protracted venous infusional 5FU. Benefits of these agents include convenience, elimination of risks from indwelling central venous catheters and a different toxic profile. They are of comparable efficacy to the Mayo regime but with less toxicity (Carmichael et al, 2002; Douillard et al, 2002; Twelves et al, 2005). Toxicity profiles of FOLFOX and FOLFIRI (Andre et al, 2004; O'Connell, 2004; Allegra and Sargent, 2005) may reduce the completion of these treatments, but fewer cycles of these regimes may be as efficacious as the completed Mayo regime. A recently published safety analysis of the XELOX NO16968 study (Schmoll et al, 2007) found more frequent treatment discontinuations with XELOX compared to the FU/LV Mayo and Roswell Park regimes; however a comparable number of patients completed 12 weeks of therapy (88 and 82%, respectively).

In conclusion, this study confirms two recent reports (Neugut et al, 2006; Dobie et al, 2006) that stage III colon cancer patients who fail to complete 5FU adjuvant chemotherapy show worse survival than patients who completed this treatment. In addition, the current study found that patients who do not complete chemotherapy may in fact have worse survival than patients treated by surgery alone. These results have implications for the delivery of oncology services. Further research is needed to identify factors that could increase both initiation and completion rates of 5FU chemotherapy from colon cancer.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Allegra C, Sargent DJ (2005) Adjuvant therapy for colon cancer – the pace quickens. N Engl J Med 352: 2746–2748

American Joint Committee on Cancer (2002) AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 6th edn, pp 113–124. New York, NY: Springer

Andre T, Boni C, Mounedji-Boudiaf L, Navarro M, Tabernero J, Hickish T, Topham C, Zaninelli M, Clingan P, Bridgewater J, Tabah-Fisch I, de Gramont A (2004) Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N Engl J Med 350: 2343–2351

Andre T, Colin P, Louvet C, Gamelin E, Bouche O, Achille E, Colbert N, Boaziz C, Piedbois P, Tubiana-Mathieu N, Boutan-Laroze A, Flesch M, Buyse M, de Gramont A (2003) Semimonthly versus monthly regimen of fluorouracil and leucovorin administered for 24 or 36 weeks as adjuvant therapy in stage II and III colon cancer: results of a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 21: 2896–2903

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2001) Census of Population and Housing: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA). Australia: ABS, Canberra

Carmichael J, Popiela T, Radstone D, Falk S, Borner M, Oza A, Skovsgaard T, Munier S, Martin C (2002) Randomized comparative study of tegafur/uracil and oral leucovorin versus parenteral fluorouracil and leucovorin in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 20: 3617–3627

Chansky K, Benedetti J, Macdonald JS (2005) Differences in toxicity between men and women treated with 5-fluorouracil therapy for colorectal carcinoma. Cancer 103: 1165–1171

Dobie SA, Baldwin LM, Dominitz JA, Matthews B, Billingsley K, Barlow W (2006) Completion of therapy by Medicare patients with stage III colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 98: 610–619

Douillard JY, Hoff PM, Skillings JR, Eisenberg P, Davidson N, Harper P, Vincent MD, Lembersky BC, Thompson S, Maniero A, Benner SE (2002) Multicenter phase III study of uracil/tegafur and oral leucovorin versus fluorouracil and leucovorin in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 20: 3605–3616

Goyle S, Maraveyas A (2005) Chemotherapy for colorectal cancer. Dig Surg 22: 401–414

Iwashyna TJ, Lamont EB (2002) Effectiveness of adjuvant fluorouracil in clinical practice: a population-based cohort study of elderly patients with stage III colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 20: 3992–3998

Jessup JM, Stewart A, Greene FL, Minsky BD (2005) Adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer: implications of race/ethnicity, age, and differentiation. JAMA 294: 2703–2711

Jodrell DI, Stewart M, Aird R, Knowles G, Bowman A, Wall L, McLean C (2001) 5-fluorouracil steady state pharmacokinetics and outcome in patients receiving protracted venous infusion for advanced colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 84: 600–603

Katopodis O, Ross P, Norman AR, Oates J, Cunningham D (2004) Sixty-day all-cause mortality rates in patients treated for gastrointestinal cancers, in randomised trials, at the Royal Marsden Hospital. Eur J Cancer 40: 2230–2236

Kawakami K, Ruszkiewicz A, Bennett G, Moore J, Watanabe G, Iacopetta B (2003) The folate pool in colorectal cancers is associated with DNA hypermethylation and with a polymorphism in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase. Clin Cancer Res 9: 5860–5865

Meta-analysis Group in Cancer (1998) Toxicity of fluorouracil in patients with advanced colorectal cancer: effect of administration schedule and prognostic factors. J Clin Oncol 16: 3537–3541

Milano G, Etienne MC, Cassuto-Viguier E, Thyss A, Santini J, Frenay M, Renee N, Schneider M, Demard F (1992) Influence of sex and age on fluorouracil clearance. J Clin Oncol 10: 1171–1175

Milano G, Etienne MC, Renee N, Thyss A, Schneider M, Ramaioli A, Demard F (1994) Relationship between fluorouracil systemic exposure and tumor response and patient survival. J Clin Oncol 12: 1291–1295

Moertel CG, Fleming TR, Macdonald JS, Haller DG, Laurie JA, Goodman PJ, Ungerleider JS, Emerson WA, Tormey DC, Glick JH, Veeder MH, Mailliard JA (1990) Levamisole and fluorouracil for adjuvant therapy of resected colon carcinoma. N Engl J Med 322: 352–358

Neugut AI, Matasar M, Wang X, McBride R, Jacobson JS, Tsai WY, Grann VR, Hershman DL (2006) Duration of adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer and survival among the elderly. J Clin Oncol 24: 2368–2375

NIH consensus conference (1990) Adjuvant therapy for patients with colon and rectal cancer. JAMA 264: 1444–1450

O'Connell MJ (2004) Current status of adjuvant therapy for colorectal cancer. Oncology 18: 751–755

O'Connell MJ, Mailliard JA, Kahn MJ, Macdonald JS, Haller DG, Mayer RJ, Wieand HS (1997) Controlled trial of fluorouracil and low-dose leucovorin given for 6 months as postoperative adjuvant therapy for colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 15: 246–250

Pinedo HM, Peters GF (1988) Fluorouracil: biochemistry and pharmacology. J Clin Oncol 6: 1653–1664

Popescu RA, Norman A, Ross PJ, Parikh B, Cunningham D (1999) Adjuvant or palliative chemotherapy for colorectal cancer in patients 70 years or older. J Clin Oncol 17: 2412–2418

Poplin EA, Benedetti JK, Estes NC, Haller DG, Mayer RJ, Goldberg RM, Weiss GR, Rivkin SE, Macdonald JS (2005) Phase III Southwest Oncology Group 9415/Intergroup 0153 randomized trial of fluorouracil, leucovorin, and levamisole versus fluorouracil continuous infusion and levamisole for adjuvant treatment of stage III and high-risk stage II colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 23: 1819–1825

Saini A, Norman AR, Cunningham D, Chau I, Hill M, Tait D, Hickish T, Iveson T, Lofts F, Jodrell D, Ross PJ, Oates J (2003) Twelve weeks of protracted venous infusion of fluorouracil (5-FU) is as effective as 6 months of bolus 5-FU and folinic acid as adjuvant treatment in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 88: 1859–1865

Schmoll HJ, Cartwright T, Tabernero J, Nowacki MP, Figer A, Maroun J, Price T, Lim R, Van Cutsem E, Park YS, McKendrick J, Topham C, Soler-Gonzalez G, de Braud F, Hill M, Sirzen F, Haller DG (2007) Phase III trial of capecitabine plus oxaliplatin as adjuvant therapy for stage III colon cancer: a planned safety analysis in 1, 864 patients. J Clin Oncol 25: 102–1099

Sloan JA, Goldberg RM, Sargent DJ, Vargas-Chanes D, Nair S, Cha SS, Novotny PJ, Poon MA, O'Connell MJ, Loprinzi CL (2002) Women experience greater toxicity with fluorouracil-based chemotherapy for colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 20: 1491–1498

Sundararajan V, Mitra N, Jacobson JS, Grann VR, Heitjan DF, Neugut AI (2002) Survival associated with 5-fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy among elderly patients with node-positive colon cancer. Ann Intern Med 136: 349–357

Tebbutt NC, Norman AR, Cunningham D, Allen M, Chau I, Oates J, Hill M (2000) Analysis of the time course and prognostic factors determining toxicity due to infused fluorouracil. Br J Cancer 88: 1510–1515

Twelves C, Wong A, Nowacki MP, Abt M, Burris III H, Carrato A, Cassidy J, Cervantes A, Fagerberg J, Georgoulias V, Husseini F, Jodrell D, Koralewski P, Kroning H, Maroun J, Marschner N, McKendrick J, Pawlicki M, Rosso R, Schuller J, Seitz JF, Stabuc B, Tujakowski J, Van Hazel G, Zaluski J, Scheithauer W (2005) Capecitabine as adjuvant treatment for stage III colon cancer. N Engl J Med 352: 2696–2704

Van Rijnsoever M, Elsaleh H, Joseph D, McCaul K, Iacopetta B (2003) CpG island methylator phenotype is an independent predictor of survival benefit from 5-fluorouracil in stage III colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 9: 2898–2903

Ward RL, Cheong K, Ku SL, Meagher A, O'Connor T, Hawkins NJ (2003) Adverse prognostic effect of methylation in colorectal cancer is reversed by microsatellite instability. J Clin Oncol 21: 3729–3736

Wolmark N, Rockette H, Fisher B, Wickerham DL, Redmond C, Fisher ER, Jones J, Mamounas EP, Ore L, Petrelli NJ, Spurr CL, Dimitrov N, Romond EH, Sutherland CM, Kardinal CG, Defusco PA, Jochimsen P (1993) The benefit of leucovorin-modulated fluorouracil as postoperative adjuvant therapy for primary colon cancer: results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project protocol C-03. J Clin Oncol 11: 1879–1887

Zalcberg J, Kerr D, Seymour L, Palmer M (1998) Haematological and non-haematological toxicity after 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin in patients with advanced colorectal cancer is significantly associated with gender, increasing age and cycle number. Tomudex International Study Group. Eur J Cancer 34: 1871–1875

Acknowledgements

Dr Melinda Morris was supported by a Surgeon-Scientist Fellowship from the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Morris, M., Platell, C., Fritschi, L. et al. Failure to complete adjuvant chemotherapy is associated with adverse survival in stage III colon cancer patients. Br J Cancer 96, 701–707 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603627

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603627

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Rural versus urban commuting patients with stage III colon cancer: is there a difference in treatment and outcome?

Surgical Endoscopy (2023)

-

Does fragmented cancer care affect survival? Analysis of gastric cancer patients using national insurance claim data

BMC Health Services Research (2022)

-

Fragmentation of care and colorectal cancer survival in South Korea: comparisons according to treatment at multiple hospitals

Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology (2022)

-

Association among the prognostic nutritional index, completion of adjuvant chemotherapy, and cancer-specific survival after curative resection of stage II/III gastric cancer

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2020)

-

Minimally invasive surgery for stage III colon adenocarcinoma is associated with less delay to initiation of adjuvant systemic therapy and improved survival

Surgical Endoscopy (2019)