Abstract

This qualitative systematic review of the clinical methodology used in randomised, controlled trials of oral opioids (morphine, hydromorphone, oxycodone) for cancer pain underlines the difficulties of good pain research in palliative care. The current literature lacks placebo-controlled superiority trials. Recommendations for future research are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Conducting randomised controlled trials in the palliative-care patient population is a challenge. It is difficult to recruit patients and to conduct trials successfully due to the serious nature of the illness and the inevitability of symptom progression.

Pain trials are especially prone to error. Pain is a subjective experience and as such is influenced by a number of variables that are difficult to control, both in the clinical situation, and in the context of a controlled trial. Psychological factors such as anxiety and depression may influence the perception of pain and even the effect of opioids (Wasan et al, 2005). A critical review of the literature on cancer pain found strong evidence for a relationship between psychosocial factors and chronic cancer pain (Zaza and Baine, 2002). The authors concluded that cancer pain assessment should include routine screening for psychological distress. Cognitive style such as catastrophising may also contribute to the intensity of pain (Sullivan et al, 2001; Keefe et al, 2005). Depression, anxiety and sleep disturbance are common in the cancer patient population. It would therefore seem prudent to consider these variables when designing cancer pain trials.

The objective of this review was to conduct a systematic investigation of specific oral opioid (morphine, oxycodone, hydromorphone) pain trials in adult cancer patients in order to

-

1

evaluate the general methodological quality of randomised, controlled trials of opioids in cancer pain

-

2

identify factors related to poor methodological quality

-

3

investigate whether psychological factors are routinely addressed in opioid trials

-

4

make recommendations for future clinical research on pain treatment in palliative care

It was decided to restrict the review to oral opioids in order to have consistency and to minimise variation in the studies, concentrating on study drugs that behave in a similar manner.

Materials and methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

Search terms were oxycodone, morphine, hydromorphone, cancer, using the Boolean operators ‘OR’ and ‘AND’. The search was performed in the Cochrane Central Register of controlled trials (CENTRAL) (current issue), The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (current issue), MEDLINE (1966 – January 2005) and EMBASE (1980 – January 2005). Abstracts and unpublished reports were not considered. There was no language restriction. The date of the most recent search (CENTRAL) was 9 November 2005.

All identified records from each of the databases were examined. Studies in adult patients 18 years and above involving treatment of chronic cancer pain with specific oral opioid (morphine, oxycodone or hydromorphone) were considered. The titles and abstracts of studies were examined independently by two reviewers (RFB, EK) and potentially relevant studies were retrieved for assessment for inclusion in the review. Each trial report that appeared to meet the criteria was independently assessed for inclusion by three reviewers (RB, CE, EK).

Validity assessment

Study quality (randomisation/allocation concealment; details of blinding measures, withdrawals and dropouts; overall quality score) were evaluated using the three item (1–5) Oxford Quality scale (Jadad et al, 1996). Validity was evaluated using the five item (1–16) Oxford Pain Validity Scale (OPVS) (Smith et al, 2000). Scoring was performed independently by three reviewers (RFB, CE, EK). The statistical analyses employed in the individual trials used were assessed by a statistician (TW).

Data abstraction

A data extraction form was designed and the following data items were collected:

-

1

Publication details,

-

2

Patient population, number of patients

-

3

Exclusion criteria

-

4

Description of pain

-

5

Psychological variables

-

6

Design, study duration and follow-up

-

7

Outcome measures

-

8

Withdrawals and adverse effects

-

9

Acknowledgement of pharmaceutical industry

-

10

Statistics

Study characteristics

Randomised trials, described as double-blind and having either placebo or active controls were included.

Quantitative data synthesis

This is a qualitative systematic review. Quantitative analysis was not performed.

Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses (QUOROM) (Moher et al, 1999) guidelines were followed.

Results

Study characteristics

Thirty-four randomised, double-blinded trials were identified. The characteristics of the included trials are summarised in Table 1. Seventeen trials were described as multicentre trials, or enrolled patients from more than one centre. In one trial, 85 patients were recruited from 30 general practice, hospital or hospice locations (O’Brien et al, 1997). A total of seven trials enrolled a hundred or more patients in each trial. Six of these were multicentre trials with the number of centres involved ranging from seven to 19. The maximum number of patients enrolled in any one trial was 180. This was a multicentre trial involving 17 centres (Kaplan et al, 1998). In general, the multicentre trials recruited larger numbers of patients than the single-centre trials. The mean number of patients enrolled in a multicentre trial was 80, more than twice that of the mean number in a single-centre trial.

Patients

The total number of patients enrolled was 1864. Patients recently or currently receiving radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy were specifically excluded in 20 of 34 trials. In two of these trials (Kaplan et al, 1998; Parris et al, 1998), the protocol was subsequently changed to facilitate patient inclusion.

Trial design

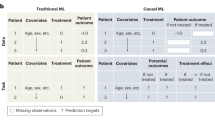

Twenty-six trials had crossover, and eight had parallel group design; 26 trials used double-dummy technique. Thirty-three of the 34 trials were equivalency studies.

Only one study (Hoskin et al, 1989) had a placebo control, while another study had a placebo arm in the first phase (Broomhead et al, 1997). Only nine studies described the process of randomisation.

Quality, validity and sensitivity

Quality scores were generally high with a mean of 4, while validity scores were somewhat lower with a mean of 10 on the OPVS scale of 1–16.

Only nine trials were scored as sensitive. In the remaining trials, baseline levels of pain were insufficient to be able to measure a change following treatment, baseline levels of pain could not be assessed or internal sensitivity was not demonstrated.

Group size

Six studies had a group size between 10 and 20, while 28 studies had a group size over 20.

Duration

Ten trials had a duration of 7 days or less. Fourteen trials had a duration of between 7 and 14 days. Ten trials lasted longer than 2 weeks. The trial with the longest duration lasted maximum 35 days (Stambaugh et al, 2001).

Withdrawals/dropouts

Twenty-nine studies had a withdrawal/dropout/nonevaluable rate over 10%, with 12 studies exceeding 30%. Six trials had a withdrawal rate of 40% or more, including one study with a maximum duration of 28 days and a withdrawal rate of 44% (Coluzzi et al, 2001). The most common reason for failure to complete the study was adverse effects, followed by insufficient pain relief and deterioration due to disease progression. In general, trials of longer duration had larger numbers of patients who failed to complete the study. Twenty-four studies had a duration of more than 1 week, with 16 studies lasting 2 weeks or longer.

Pain description and assessment

Only 11 of 34 studies (Table 1, trials 5, 6, 8, 12, 15, 18, 19, 26, 28, 30, 34) included a description of the pain. In two of these (Deschamps et al, 1992; Stambaugh et al, 2001), the description was restricted to the location of the pain. Five trials (Hays et al, 1994; Bruera et al, 1996, 1998, 2004; Hagen and Babul, 1997) evaluated patients using the Edmonton staging system which classifies pain as visceral, bone, soft tissue, neuropathic, mixed, unknown and incidental or nonincidental. However, only three of these trials reported data on the type of pain.

Pain intensity was assessed in all trials: in nine trials using visual analogue scale (VAS), in seven using verbal rating scale (VRS) and in four trials using a numerical rating scale (NRS). Thirteen trials used VAS in addition to VRS. One trial used a nonvalid assessment, nurse-rated VRS that was later converted to a numerical score. Five trials rated pain relief in addition to pain intensity. In three of these trials, pain relief was assessed using VAS and in two trials using VRS.

The criteria for adequate/inadequate pain relief was clearly defined in only eight of the 34 trials. The criteria differed for each of these trials and for adequate pain relief included: ‘maximum 3 on a 7 point VRS, and not more than two daily requests for rescue analgesia’ (Klepstad et al, 2003); ‘no need for dose adjustment for three or more days and no morphine sulphate solution intake exceeding 50% of the daily morphine dosage supplied by the test drug’ (Deschamps et al, 1992); ‘no more than three supplementary doses of immediate release morphine per day’ (Portenoy et al, 1989); ‘required daily rescue doses over 2 days interval not more than 20% of the total daily morphine doses’ (Cundiff et al, 1989); ‘over a 48-h period, the q12h dose was unchanged, less than two supplemental analgesic doses were taken per day, the dosing regimen for any non-opioids or adjuvants was unchanged, and the patient reported that pain control was acceptable and any side effects were tolerable’ (Mucci-LoRusso et al, 1998). Inadequate pain relief was defined as: ‘more than two doses of rescue medication/24 h, or moderately severe global pain score’ (Stambaugh et al, 2001); ‘despite dose escalation, pain intensity rating more than three on a five point VRS’ (Wilder-Smith et al, 1994). One study defined a clinically meaningful difference in VAS scores as 25 mm on a 100 mm scale (Walsh et al, 1992).

Psychological variables and sleep (see Table 1)

Despite the fact that anxiety and depression are known to influence the perception of pain, only three trials (Walsh, 1985; Walsh et al, 1992; Finn et al, 1993) assessed and reported these variables. In addition, one of these trials and two others assessed and reported ‘mood’ and a third trial used Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) ratings of mood and enjoyment of life. A further five trials used the Edmonton staging system that includes assessment of the degree of psychological stress in order to calculate a prognosis score, but did not report data on psychological variables. One of these trials in addition used the Folstein Mini-Mental status. One trial (Heiskanen and Kalso, 1997) used the Modified Specific Drug Effects Questionnaire (MSDEQ) which includes questions such as ‘Do you feel anxious?’ and ‘Do you feel relaxed ?’. Mucci-LoRusso et al (1998) used a quality of life questionnaire, the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT G), which includes an emotional subscale. Nine trials assessed sleep and seven of these provided data.

Adverse effects

All trials included data on adverse events. Twenty-five trials assessed adverse event severity using verbal or categorical rating scales, or VAS. Eighteen trials provided data from these measurements.

Adverse effect intensity was rated using VAS in nine trials, NRS in one trial and by categorical or verbal rating scale in 13 trials. One trial used both VAS and categorical scales. In one trial, where severity was investigator-rated, it is unclear which method was used (Kaplan et al, 1998).

A total of 18 trials provided dichotomous data on the incidence of adverse effects.

These included all nine studies not grading the intensity of adverse effects. Only nine of the 25 studies grading adverse effect intensity provided dichotomous data on incidence.

Statistical methods

The statistical methods used are summarised in Table 2. All 34 trials are judged to have chosen appropriate statistical methods on most of the analyses; however, some problems were identified regarding the statistical analysis in 18 trials.

In nine trials (Table 2, trials 1, 4, 10, 12, 15, 19, 20, 25, 33), the authors concluded that the test drug was equally effective as the comparator drug. However, the tests performed only show no evidence of effect, not evidence of no effect.

Only 10 of 34 trials reported to have performed pre-hoc sample-size calculation. In three trials, some posterior power calculations were performed (Portenoy et al, 1989; Walsh et al, 1992; Mignault et al, 1995) and in one study it is unclear whether sample-size calculation was performed (Stambaugh et al, 2001). In other words, more than 50% of the trials did not report performing power calculations.

Sponsored research

The pharmaceutical industry was specifically acknowledged in 24 of 34 trials as follows: co-authors (18 trials) financial support (four trials), manufacture of placebo double-dummy medication (one trial) morphine assays (one trial). Twenty-three of these 24 trials were equivalency studies.

Discussion

This review has identified several factors/areas that could improve the methodological quality of studies on cancer pain. The findings of the review also suggest that specific validity scores should be developed to focus more on factors that are relevant in cancer pain.

Factors influencing methodological quality

The research question

The most commonly asked research question in these trials is whether one opioid is as good as another, or whether two forms of administration of the same opioid are equally effective. However, what we really need to know is more about factors which influence the cancer patient's experience of pain, and which factors influence treatment outcome. In order to do this, we need to define good and bad responders and to identify factors that influence treatment outcome. It is important to understand why some patients do not achieve pain relief, for example with opioids, and why some patients respond to one opioid but not to another.

Trial design

Thirty-three of the 34 trials in this review are equivalency (or non-inferiority) studies comparing two opioids or two or more formulations of the same opioid.

Problems with equivalency trials: In equivalency studies of analgesics (drug A vs drug B), the focus is a comparison of the test drug with standard therapy (active control), not efficacy of the test drug per se. Equivalency trials are potentially problematic since they do not measure efficacy directly. In such a trial, the same result is consistent with three possible conclusions (Landow, 2000; Moore et al, 2003):

-

Both treatments are equally effective

-

Both treatments are equally ineffective

-

The trials were inadequate to detect differences between treatments

This problem may be avoided if the control has previously in the same patient population been shown to be effective compared to placebo. This is not the case in cancer pain, as trials having a placebo control are lacking.

Equivalency trials have important methodological limitations and must be rigorously performed if they are to produce reliable conclusions, for example needing substantially more patients than their placebo-controlled counterparts (Jones et al, 1996). The majority of trials in this review were underpowered (Figure 1).

Placebo control vs active comparator: Since patients in pain respond to placebo, we need placebo-controlled trials to reliably determine opioid efficacy. Many researchers consider that it is unethical to use a placebo control in trials of cancer pain. However, it is common to use placebo controls both in acute pain and in chronic pain trials. Morphine is accepted as the gold standard for cancer pain treatment, however high-quality placebo-controlled efficacy data in cancer pain is lacking. Extrapolation of efficacy data from trials in other patient populations is generally not advised.

Using a placebo-control where possible would also permit smaller group sizes. We do not suggest that a placebo control should be used in all cancer pain studies, but that it is feasible in certain types of trial. While it is not possible to randomise patients treated with stronger opioids to a placebo group, patients using weaker opioids may be randomised to a placebo group. Almost half of the studies included in this review recruited patients being treated with WHO step 2 (weaker) opioids. In these studies, it would have been possible to include a placebo-arm, provided the patients had free access to normal-release opioid as rescue medication, and using consumption of rescue medication as the primary outcome measure. This type of study should have a limited duration, for example 14 days, and should not present ethical problems since the treatment is similar to the clinical treatment of breakthrough pain, and would be expected to give satisfactory pain relief. Indeed, the ethics of using a placebo control in this kind of design should be compared to the potential ethical dilemma of exposing seriously ill patients to trials which do not produce reliable results due to lack of power, sensitivity or other methodological problems.

Crossover or parallel group?: A crossover design may be useful as it increases the power of the study and uses the patient as his/her own control. Crossover trials are important since they can identify clear patient preferences for one drug over another and suggest ideas for future research for the mechanisms behind these differences. Crossover trials should have as short a duration as possible in order to reduce number of withdrawals, while parallel group trials allow longer follow-up with regular assessment of outcomes.

Reporting of data

Since trial size is a general problem, efforts should be made to enable combination of data from different trials (meta-analysis). Data should be given as means±s.d., or medians+range together with responder status. The latter will help those who perform meta-analysis and also enable the researchers to further analyse the reasons why some patients respond to analgesic drugs and others do not. Adverse effects should be reported as dichotomous data. Patient treatment preference is valuable information and should be recorded. For example, some adverse effects may be more acceptable than others.

Pain description and assessment

Cancer pain may be constant, intermittent or both. It may be nociceptive, neuropathic or mixed. It may be cancer-related or treatment-related. If we are to investigate opioid efficacy, we at least need to know what kind of pain is being treated. In a parallel group study, if there are more patients in one group having neuropathic pain, then this would be expected to influence opioid treatment outcome.

As a minimum requirement, each patient included in a pain trial should be assessed specifically for pain and given a simple pain diagnosis. A common agreement on what constitutes treatment effect is important. The fact that the criteria for adequate/inadequate pain relief were clearly defined in only eight of 34 trials, and differed for each of the trials, indicates a need for standardisation.

Psychological factors

No trial specifically addressed psychological variables and the importance of these in the perception of pain. We need to know whether levels of anxiety and/or depression are similar in treatment groups, since this may affect outcome. There is a commonly held belief that the anxiety-reducing and euphoria-producing components of opioid actions account in large part for their analgesic efficacy. This would be interesting to explore in the context of a randomised trial. For example, do psychological factors such as anxiety and depression improve when pain scores improve? Is it possible that patients with specific psychological coping profiles, in particular those who cope anxiously, may have a poor response to opioid therapy? Studies of specific variables such as catastrophic thinking about pain (Sullivan et al, 1995) or acceptance of pain (McCracken et al, 2004) may be fruitful. The field is recognizing the need to develop assessment techniques that are specific to the context in which the assessment is performed (Mystakidou et al, 2005). It is possible to use compound measures that do not have to be lengthy in this setting. In the absence of any multidimensional, psychometrically validated assessment tool, the very minimum requirement would be a unidimensional tool such as a VAS of severity of anxiety or a VAS of severity of depression.

Other factors influencing opioid treatment outcome

Patients recently or currently receiving radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy were excluded in 20 of 34 trials. Whether patients receiving oncological treatment which may influence pain should be excluded from drug trials on cancer pain depends on the trial design. In studies of long duration, that is, several days or longer, including these patients is a confounding factor. In short studies, for example those examining the effect of short-acting rescue medication for breakthrough pain, including such patients should not be a problem.

A number of other factors, including gender, diurnal variation, pharmacogenetics and opioid pharmacokinetics, may influence the cancer patient's experience of pain and the outcome of opioid therapy. While it is not possible to control for all these variables, some simple measures are available and useful, such as matching groups for gender and controlling plasma opioid concentration at steady state.

Trial funding

The majority of studies were funded by the pharmaceutical industry. This may represent a source of bias, since research questions of interest for the industry, for example comparing two formulations of the same opioid, may not necessarily coincide with questions of importance for the clinician.

Conclusions and recommendations for future research

Pain is a subjective experience that is affected by many different factors. This makes pain difficult to measure and clinical pain research a challenge. The challenge is even greater in a palliative-care setting where there are special standards of care to maintain, and numerous potential confounding factors.

The data support the clinical experience that it is difficult to perform high-quality scientific trials in palliative-care pain patients. However, it is important to maintain scientific rigour and to ensure that research questions that are relevant to clinical practice are asked.

A number of methodological problems have been identified, including low trial sensitivity, too small trial size and lack of standardised measures of efficacy. Placebo-controlled efficacy trials of oral opioids for cancer pain are lacking. A placebo control is feasible in selected trials. It is important to know which type of pain is being treated and there should be a common definition of opioid efficacy. Psychological factors can influence the experience of pain and should be assessed and reported. A number of other factors have the potential for influencing opioid response, and future research should involve identifying and controlling for such factors.

Having analysed the literature we conclude that there is a need for standardisation and uniformity of design and reporting of trials. Trials must be designed to produce reliable results. This cannot be accomplished by a single researcher, but requires the collaboration of experts in several fields.

The standard opioid trial design

We propose a consensus meeting where pain researchers, systematic reviewers in pain relief, palliative-care physicians, oncologists, epidemiologists/statisticians and pain psychologists are represented. The objective of such a meeting would be to produce a standard trial design, or set of trials, for opioids in cancer pain. In addition, a checklist for the performance of trials, based on tailor-made validity scores for cancer pain (Antczak et al, 1986a, 1986b). The document produced could then be submitted to specialist organizations which have a focus on trial methodology, for example the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) and the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC), and subject to approval, made available on the respective websites. The development and dissemination of a standardised trial, together with checklist for trial performance, will help researchers to plan trials, improve study quality and validity and enable the combination of data from separate trials.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Antczak AA, Tang J, Chalmers DC (1986a) Quality assessment of randomized control trials in dental research. I. Methods. J Periodontal Res 21: 305–314

Antczak AA, Tang J, Chalmers DC (1986b) Quality assessment of randomized control trials in dental research. II. Results: periodontal research. J Periodontal Res 21: 315–321

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ (1996) Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 17: 1–12

Jones B, Jarvis P, Lewis J, Ebbutt A (1996) Trials to assess equivalence: the importance of rigorous methods. BMJ 313: 36–39

Keefe FJ, Abernethy AP, Campbell LC (2005) Psychological approaches to understanding and treating disease-related pain. Annu Rev Psychol 56: 601–630

Landow L (2000) Current issues in clinical trial design: superiority versus equivalency studies. Anesthesiology 92: 1814–1820

McCracken LM, Vowles KE, Eccleston C (2004) Acceptance of chronic pain: component analysis and a revised assessment method. Pain 107: 159–166

Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, Olkin I, Rennie D, Stroup DF (1999) Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses. Lancet 354: 1896–1900

Moore A, Edwards J, Barden J, McQuay H (2003) Bandolier's Little Book of Pain. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p 21

Mystakidou K, Tsilika E, Parpa E, Katsouda E, Galanos A, Vlahos L (2005) Assessment of anxiety and depression in advanced cancer patients and their relationship with quality of life. Qual Life Res 14: 1825–1833

Smith LA, Oldman AD, McQuay HJ, Moore RA (2000) Teasing apart quality and validity in systematic reviews: an example from acupuncture trials in chronic neck and back pain. Pain 86: 119–132

Sullivan MJ, Bishop SR, Pivik J (1995) The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: development and validation. Psychol Assessment 7: 524–532

Sullivan MJ, Thorn B, Haythornthwaite JA, Keefe F, Martin M, Bradley LA, Lefebvre JC (2001) Theoretical perspectives on the relation between catastrophizing and pain. Clin J Pain 17: 52–64

Wasan AD, Davar G, Jamison R (2005) The association between negative affect and opioid analgesia in patients with discogenic low back pain. Pain 117: 450–461

Zaza C, Baine N (2002) Cancer pain and psychosocial factors: a critical review of the literature. J Pain Symptom Manage 24: 526–542

Included studies

Boureau F, Saudubray F, d’Arnoux C, Vedrenne J, Esteve M, Roquefeuil B, Siou DK, Brunet R, Ranchere JY, Roussel P, Richard A, Laugner B, Muller A, Donnadieu S (1992) A comparative study of controlled-release morphine (CRM) suspension and CRM tablets in chronic cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage 7: 393–399

Broomhead A, Kerr R, Tester W, O’Meara P, Maccarrone C, Bowles R, Hodsman P (1997) Comparison of a once-a-day sustained-release morphine formulation with standard oral morphine treatment for cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage 14: 63–73

Bruera E, Belzile M, Pituskin E, Fainsinger R, Darke A, Harsanyi Z, Babul N, Ford I (1998) Randomized, double-blind, cross-over trial comparing safety and efficacy of oral controlled-release oxycodone with controlled-release morphine in patients with cancer pain. J Clin Oncol 16: 3222–3229

Bruera E, Palmer JL, Bosnjak S, Rico MA, Moyano J, Sweeney C, Strasser F, Willey J, Bertolino M, Mathias C, Spruyt O, Fisch MJ (2004) Methadone versus morphine as a first-line strong opioid for cancer pain: a randomized, double-blind study. J Clin Oncol 22: 185–192

Bruera E, Sloan P, Mount B, Scott J, Suarez-Almazor M (1996) A randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, crossover trial comparing the safety and efficacy of oral sustained-release hydromorphone with immediate-release hydromorphone in patients with cancer pain. J Clin Oncol 14: 1713–1717

Coluzzi PH, Schwartzberg L, Conroy JD, Charapata S, Gay M, Busch MA, Chavez J, Ashley J, Lebo D, McCracken M, Portenoy RK (2001) Breakthrough cancer pain: a randomized trial comparing oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate (OTFC) and morphine sulfate immediate release (MSIR). Pain 91: 123–130

Cundiff D, McCarthy K, Savarese JJ, Kaiko R, Thomas G, Grandy R, Goldenheim P (1989) Evaluation of a cancer pain model for the testing of long-acting analgesics. The effect of MS Contin in a double-blind, randomized crossover design. Cancer 63: 2355–2359

Deschamps M, Band PR, Hislop TG, Rusthoven J, Iscoe N, Warr D (1992) The evaluation of analgesic effects in cancer patients as exemplified by a double-blind, crossover study of immediate-release versus controlled-release morphine. J Pain Symptom Manage 7: 384–392

Finn JW, Walsh TD, MacDonald N, Bruera E, Krebs LU, Shepard KV (1993) Placebo-blinded study of morphine sulfate sustained-release tablets and immediate-release morphine sulfate solution in outpatients with chronic pain due to advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 11: 967–972

Gabrail NY, Dvergsten C, Ahdieh H (2004) Establishing the dosage equivalency of oxymorphone extended release and oxycodone controlled release in patients with cancer pain: a randomized controlled study. Curr Med Res Opin 20: 911–918

Gillette J-F, Ferme C, Moisy N, Mignot L, Schach R, Vignaux J-R, Besner JG, Caille G, Belpomme D (1997) Double-blind crossover clinical and pharmacokinetic comparison of oral morphine syrup and sustained release morphine sulfate capsules in patients with cancer-related pain. Clin Drug Invest 14: 22–27

Hagen NA, Babul N (1997) Comparative clinical efficacy and safety of a novel controlled-release oxycodone formulation and controlled-release hydromorphone in the treatment of cancer pain. Cancer 79: 1428–1437

Hanks GW, Hanna M, Finlay I, Radstone DJ, Keeble T (1995) Efficacy and pharmacokinetics of a new controlled-release morphine sulfate 200-mg tablet. J Pain Symptom Manage 10: 6–12

Hanks GW, Twycross RG, Bliss JM (1987) Controlled release morphine tablets: a double-blind trial in patients with advanced cancer. Anaesthesia 42: 840–844

Hays H, Hagen N, Thirlwell M, Dhaliwal H, Babul N, Harsanyi Z, Darke AC (1994) Comparative clinical efficacy and safety of immediate release and controlled release hydromorphone for chronic severe cancer pain. Cancer 74: 1808–1816

Heiskanen T, Kalso E (1997) Controlled-release oxycodone and morphine in cancer related pain. Pain 73: 37–45

Hoskin PJ, Poulain P, Hanks GW (1989) Controlled-release morphine in cancer pain. Is a loading dose required when the formulation is changed? Anaesthesia 44: 897–901

Kalso E, Vainio A (1990) Morphine and oxycodone hydrochloride in the management of cancer pain. Clin Pharmacol Ther 47: 639–646

Kaplan R, Parris WC-V, Citron ML, Zhukovsky D, Reder RF, Buckley BJ, Kaiko RF (1998) Comparison of controlled-release and immediate-release oxycodone tablets in patients with cancer pain. J Clin Oncol 16: 3230–3237

Klepstad P, Kaasa S, Jystad A, Hval B, Borchgrevink PC (2003) Immediate- or sustained-release morphine for dose finding during start of morphine to cancer patients: a randomized, double-blind trial. Pain 101: 193–198

Knudsen J, Mortensen SM, Eikard B, Henriksen H (1985) Morphine depot tablets compared with conventional morphine tablets in the treatment of cancer pain (Danish). Ugeskr Laeger 147: 780–784

Lauretti GR, Oliveira GM, Pereira NL (2003) Comparison of sustained-release morphine with sustained-release oxycodone in advanced cancer patients. Br J Cancer 89: 2027–2030

Melzack R, Mount BM, Gordon JM (1979) The Brompton mixture versus morphine solution given orally: effects on pain. Can Med Assoc J 120: 435–438

Mignault GG, Latreille J, Viguie F, Richer P, Lemire F, Harsanyi Z, Stewart JH (1995) Control of cancer-related pain with MS Contin: a comparison between 12-hourly and 8-hourly administration. J Pain Symptom Manage 10: 416–422

Moriarty M, McDonald CJ, Miller AJ (1999) A randomised crossover comparison of controlled release hydromorphone tablets with controlled release morphine tablets in patients with cancer pain. J Drug Assess 2: 41–48

Mucci-LoRusso P, Berman BS, Silberstein PT, Citron ML, Bressler L, Weinstein SM, Kaiko RF, Buckley BJ, Reder RF (1998) Controlled-release oxycodone compared with controlled-release morphine in the treatment of cancer pain: a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study. Eur J Pain 2: 239–249

O’Brien T, Mortimer PG, McDonald CJ, Miller AJ (1997) A randomized crossover study comparing the efficacy and tolerability of a novel once-daily morphine preparation (MXL capsules) with MST Continus tablets in cancer patients with severe pain. Palliat Med 11: 475–482

Parris WC-V, Johnson Jr BW, Croghan MK, Moore MR, Khojasteh A, Reder RF, Kaiko RF, Buckley BJ (1998) The use of controlled-release oxycodone for the treatment of chronic cancer pain: a randomized, double-blind study. J Pain Symptom Manage 16: 205–211

Portenoy RK, Maldonado M, Fitzmartin R, Kaiko RF, Kanner R (1989) Oral controlled-release morphine sulfate. Analgesic efficacy and side effects of a 100-mg tablet in cancer pain patients. Cancer 63: 2284–2288

Stambaugh JE, Reder RF, Stambaugh MD, Stambaugh H, Davis M (2001) Double-blind, randomized comparison of the analgesic and pharmacokinetic profiles of controlled- and immediate-release oral oxycodone in cancer pain patients. J Clin Pharmacol 41: 500–506

Thirlwell MP, Sloan PA, Maroun JA, Boos GJ, Besner JG, Stewart JH, Mount BM (1989) Pharmacokinetics and clinical efficacy of oral morphine solution and controlled-release morphine tablets in cancer patients. Cancer 63: 2275–2283

Walsh TD (1985) Clinical evaluation of slow-release morphine tablets. In Advances in Pain Research and Therapy, Fields HL et al (eds) pp 727–731. New York: Raven Press

Walsh TD, MacDonald N, Bruera E, Shepard KV, Michaud M, Zanes R (1992) A controlled study of sustained-release morphine sulfate tablets in chronic pain from advanced cancer. Am J Clin Oncol 15: 268–272

Wilder-Smith CH, Schimke J, Osterwalder B, Senn H-J (1994) Oral tramadol, a mu-opioid agonist and monoamine reuptake-blocker, and morphine for strong cancer-related pain. Ann Oncol 5: 141–146

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Research Council of Norway and from the Regional Centre of Excellence for Palliative Care, Western Norway.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Bell, R., Wisløff, T., Eccleston, C. et al. Controlled clinical trials in cancer pain. How controlled should they be? A qualitative systematic review. Br J Cancer 94, 1559–1567 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603162

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603162

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Qualitative inquiry: a method for validating patient perceptions of palliative care while enrolled on a cancer clinical trial

BMC Palliative Care (2014)

-

Pharmacoeconomic Impact of Adverse Events of Long-Term Opioid Treatment for the Management of Persistent Pain

Clinical Drug Investigation (2011)

-

Enhancing the quality of clinical trials in cancer pain first requires that pain assessment methods are appropriately understood and used

British Journal of Cancer (2006)