Abstract

Platinum-based combination chemotherapy has been proven to be superior to single-agent platinum in the treatment of relapsed ovarian cancer after a treatment-free interval of more than 6 months. A response rate of 41% was previously reported by our group using a combination of epirubicin, cisplatin and 5-FU in patients who relapsed within 12 months, we therefore assessed a similar, but more convenient combination of epirubicin, carboplatin and capecitabine in this phase-I/II trial. In total, 18 patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma, who had not received more than two lines of chemotherapy and the treatment-free interval exceeded 6 months were treated with carboplatin AUC5, epirubicin 50 mg m−2 and capecitabine at several dose levels on continuous 21 day cycles and 14 of 21 day cycles. Patients were assessed for toxicity and by CT and CA-125 for response. The overall response rate was 61.1%, with three complete and eight partial responses. Grade 3/4 haematological toxicity was seen in 10 out of 18 patients and caused dose reductions and treatment delays. The combination of epirubicin, carboplatin and capecitabine showed good activity but caused excessive toxicity. A phase-II trial using carboplatin and capecitabine is underway.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Ovarian cancer remains the number one cause of death from gynaecological neoplasms in the Western world (Greenlee et al, 2001). Response rates to first-line chemotherapy in women with ovarian cancer are high but most patients relapse and need further treatment. Recurrent disease is incurable (Ozols, 2002); however, many patients can obtain good palliation from further treatment, particularly if they obtain an objective response (Cannistra, 2002).

Platinum-based combination chemotherapy has been proven to be superior to single-agent carboplatin in patients with so-called chemo-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer in terms of response rate and progression-free survival in two randomised studies and overall survival in one of them (Parmar et al, 2003; Pfisterer et al, 2005). Chemo-sensitive relapse is usually defined as one that occurs after a platinum-free interval of over 6 months.

However, there is uncertainty concerning which agent to add to carboplatin in this situation: data on the activity of single-agent non-platinum therapy have shown similar efficacy for paclitaxel (Piccart et al, 2000), docetaxel (Kaye et al, 1997), epirubicin (Havsteen et al, 1996), gemcitabine (Shapiro et al, 1996), liposomal doxorubicin (Muggia et al, 1997; Gordon et al, 2001), etoposide (Rose et al, 1998), topotecan (Gore et al, 2002), oxaliplatin (Chollet et al, 1996), and vinorelbine (Sorensen et al, 2001). There is one analysis that shows superiority for caelyx over topotecan in patients with a progression-free interval >6 months but this was a subset analysis (Gordon et al, 2004).

Our group has shown that patients re-challenged with platinum using a combination of epirubicin, cisplatin and continuous infusional 5-fluoruracil (ECF) for recurrent ovarian cancer have a response rate of 41%. In this study, the patients had relapsed within 12 months of platinum treatment (Ahmed et al, 1995). Considerable morbidity can be associated with an indwelling central venous catheter for the administration of 5-FU, such as pneumothorax at the time of insertion, sepsis or thrombosis. We therefore decided to investigate the substitution of continuous intravenous 5-FU in the ECF regimen with capecitabine (Xeloda), an orally bio-available fluoropyrimidine carbamate. The conversion of the prodrug capecitabine to 5-fluoruracil is dependent on thymidine phosphorylase, an enzyme preferentially expressed in malignant cells, and is considered tumour-selective (Ishikawa et al, 1998; Schilsky, 2000). Capecitabine has been demonstrated to have activity in relapsed ovarian cancer in three recently published phase II trials (Boehmer and Jaeger, 2002; Vasey et al, 2003; Rischin et al, 2004). In addition, we replaced the cisplatin with carboplatin to make the regimen more convenient for patients.

The aim of this study was to identify the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of capecitabine in combination with epirubicin and carboplatin in patients with relapsed ovarian cancer. We planned to identify safe doses of the drugs in this combination so that a phase-III trial could be performed. We also evaluated the response rate to carboplatin, capecitabine and epirubicin (ECarboX) as a secondary end point.

Patients and methods

Patients were eligible if they had recurrent, histologically verified epithelial ovarian carcinomas, had not received more than two lines of chemotherapy and the treatment-free interval between the cessation of the previous chemotherapy and documented relapse exceeded 6 months.

Additional inclusion criteria were: age 18–80 years, ECOG performance status 0–2, life expectancy >3 months, measurable disease as assessed by CT in accordance with WHO guidelines, GFR⩾60 ml min−1 as measured by EDTA clearance or 24 h urine collection, bilirubin <2 times ULN, adequate bone marrow function with WBC>3000 μl−1, neutrophils >1500 μl−1, platelets >100 000 μl−1. Fully informed written consent was obtained from all patients.

Patients were excluded for any serious uncontrolled medical condition, a significantly abnormal ECG or cardiac history of having a LVEF<LLN measured by MUGA scan or echocardiogram, or any medical or psychiatric condition, which would impair the patients’ ability to give informed consent.

The protocol and the consent form were approved by the local institutional ethics committee and protocol review board.

Treatment plan

Carboplatin was administered at a dose level of AUC5 intravenously over a 1 h infusion once every 3 weeks, epirubicin was given as an intravenous bolus at a dose of 50 mg m−2 once every 3 weeks. Administration of capecitabine was by the oral route and the doses to be used in successive cohorts of patients were: capecitabine 375 mg m−2 BD (level 1), 500 mg m−2 BD (level 2) daily throughout a 21-day cycle, and 625 mg m−2 BD (level 3) for days 1–14 of a 21-day cycle. The decision to increase from level 1 to 2 was based on the toxicity experienced in the first cycle of each cohort of three patients. Escalation was to be carried out if dose-limiting toxicity was not seen in the first three patients in each cohort. There were two additional dose levels (−1 and −2). Patients treated at these dose levels received capecitabine for days 1–14 on a 21-day cycle at 500 mg m−2 BD (level −1) and 375 mg m−2 BD (level −2) daily, respectively. These dose levels were introduced when it became clear that a 14 rather than 21-day schedule for capecitabine was necessary if this three-drug regimen was to be administered safely. All patients received prophylactic antiemetic therapy prior to administration of carboplatin.

Six cycles of chemotherapy were planned for each responding patient or those with stable disease. Criteria for withdrawal from the study were as follows: intolerable side effects as judged by the investigator or the patient, patient decision to discontinue treatment for any reason, recurrent grade 3 or 4 drug-related toxicity despite dose modifications, progression of tumour and serious allergic reactions to any of the study drugs. Dose reductions for haematological toxicity were performed according to the protocol. Patients who withdrew from the study were assessed for toxicity and response. Dose limiting toxicity (DLT) was defined as grade IV myelotoxicity, which was either prolonged (>7 days) or complicated by bleeding or infection, or grade III nonhaematological toxicity occurring in the first cycle.

Assessment of safety and efficacy

Toxicity and adverse events were reported according to NCIC-CTC after each cycle.

Response was assessed by CT according to WHO criteria after cycle 3 and 6; in addition, tumour marker CA-125 was used to monitor response and was measured before each cycle. Complete response was defined as normalisation of radiological appearances and normalisation of CA-125.

Results

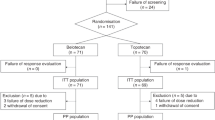

In total, 18 patients with relapsed epithelial ovarian carcinoma and a median age of 58 years (range, 43–70 years) were enrolled from October 2002 until June 2004. A total of 13 patients had only received one line of chemotherapy previously. The other five patients received ECarboX as third-line treatment (Table 1). All patients had a platinum-free interval >6 months and were thus considered platinum-sensitive. The median platinum-free interval was 18.6 months with a range of 8.7–55.4 months. One of the patients had previously received radiotherapy to the brain for cerebral metastases.

Three patients were assigned to dose level 1 (capecitabine 375 mg m−2 BD q21) and five patients to dose level 2 (capecitabine 500 mg m−2 BD q21). Following a protocol amendment, one patient was treated at dose level 3 (capecitabine 625 mg m−2 BD q14). Six patients received dose level −1 (capecitabine 500 mg m−2 BD q14) and three patients dose level −2 (capecitabine 375 mg m−2 BD q14), respectively.

Toxicity

At dose level 1, no DLT was experienced in the first cycle, although one patient had grade 3 neutropenia and required subsequent dose delays and dose reductions as per protocol. Another patient experienced grade 3 diarrhoea and recurrent episodes of neutropenia on cycles 2 and 4. She required a >50% dose reduction of capecitabine and epirubicin and was treated off-study after cycle 4 due to the delays of treatment. She did however have a complete response.

At dose level 2, the cohort was expanded to five patients after one patient had experienced a DLT (bleeding) during the first cycle and required a 1-week delay of cycle 2. Two out of five patients suffered from prolonged neutropenia following the first cycle, which prevented retreatment with carboplatin on day 22. One of these patients had another 3-week delay of her third cycle due to grade 3 neutropenia and therefore came off-trial; she had progressive disease after cycle three. Another patient experienced grade 3 fatigue.

Following a protocol amendment due to the high rate of prolonged grade 3 neutropenia, we treated patients with a shortened schedule of capecitabine (14 out of 21 days). One patient was treated at 625 mg m−2 BD for 14 days on a 21-day cycle (level 3). She developed small bowel obstruction following the administration of the first cycle of chemotherapy and required surgery; she became neutropenic while awaiting surgery. The patient was subsequently treated off-study with another four courses at reduced dose and achieved a complete response. No further patients were enrolled at this dose level as this severe adverse event was felt to represent DLT.

Three out of six patients on dose level −1 required delays of day 22 due to prolonged grade 3 neutropenia, one had grade 3 thrombocytopenia and one grade 3 palmar-plantar-syndrome (PPS). All other side effects were infrequent. After another dose de-escalation, three patients were treated at level −2: one patient had grade 4 stomatitis and one grade 3 neutropenia.

A total of 37 cycles of chemotherapy (out of 77 delivered on study) had to be postponed due to toxicity. The median delay was 2 weeks per patient (range 0–5 weeks).

The MTD was dose level 2 with capecitabine given at 500 mg m−2 BD for 21 days of a 21-day cycle. This schedule was not considered suitable for taking forward to a larger multicentre trial because of the frequent incidence of prolonged neutropenia. 14-day courses of capecitabine were better tolerated; this schedule, however, still caused Grade 3/4 haematological toxicity requiring dose reductions and delays in 60% (six out of 10) of the patients (Table 2).

Efficacy

In total, 11 patients (61.1%) showed either a complete (three patients; 16.7%) or a partial response (eight patients; 44.4%), five (27.7%) had stable disease. Only two (11.1%) of the patients had progressive disease on treatment.

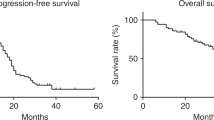

The median progression-free survival was 8.3 months, the median follow-up time was 18 months (range 7.3–27.2 months). Median overall survival has not yet been reached and 14 patients are still alive.

Discussion

We have performed a phase I/II trial using carboplatin, epirubicin and capecitabine in platinum-sensitive patients with relapsed epithelial ovarian cancer. The rationale behind this regimen was that we had previously demonstrated a high response rate in patients treated with ECF for relapsed ovarian cancer at the Royal Marsden Hospital (Webb et al, 2000), and wanted to investigate the feasibility of a more convenient route of administration for a fluoropyrimidine. We used capecitabine instead of 5-FU as this enables delivery of the fluoropyrimidine in an oral form rather than via a continuous infusion requiring a PICC line, without compromising on efficacy as shown for colorectal cancer in randomised trials (Hoff et al, 2001; Van Cutsem et al, 2001). We initially chose to administer continuous capecitabine to mirror continuously infused 5-FU, but this proved impractical.

In addition, carboplatin has been shown to be equally active as cisplatin in advanced ovarian cancer (Swenerton et al, 1992; Taylor et al, 1994; Ozols et al, 2003), but is less toxic and easier to administer. This was the reason why we changed the cisplatin to carboplatin for the ECarboX regimen.

We found the ECarboX regimen to be active with three patients having a CR and eight patients a PR, giving an overall response rate (ORR) of 61.1%. CR was seen in patients at dose level 1 and dose level 3, PR was seen on all other dose levels. The median progression-free survival of 8.3 months is consistent with the results seen in this patient group in other phase I/II trials (Kose et al, 2005).

However, ECarboX proved problematic to deliver as prescribed. The overall toxicity was high in terms of haematological side effects, although surprisingly no major infectious complications arose from the neutropenic episodes. Prolonged myelotoxicity was a significant feature even when administration of capecitabine was shortened. All other side effects were infrequent and manageable.

One patient's treatment was complicated by a cerebrovascular event and a deep venous thrombosis during cycle two. She was taken off study and treated with single-agent carboplatin. There are reports suggesting capecitabine can induce acute coronary syndromes (Schnetzler et al, 2001; Frickhofen et al, 2002), but no reports of cerebrovascular events caused by capecitabine exist. It remains unclear whether this patient's CVA was related to chemotherapy. The patient who developed intestinal obstruction following the first course of treatment was thought to have disease progression rather than a side effect from the regimen.

The management of patients with platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer is receiving increasing attention. A retrospective analysis (Dizon et al, 2002) of patients who received carboplatin/paclitaxel at relapse demonstrated an OR of 69.7% and a progression-free interval of 13 months. A total of 61.9% of these patients had already received carboplatin/paclitaxel as first-line treatment. However, 77% had a treatment-free interval >12 months and therefore would be considered good-risk patients. Toxicity was acceptable although six patients required admission to hospital for adverse events.

The ICON4/AGO-OVAR-2.2 trial investigated carboplatin/paclitaxel vs conventional platinum-based chemotherapy in women with relapsed ovarian cancer (Parmar et al, 2003). In this trial, about 40% of patients had received a platinum/paclitaxel combination previously as first-line treatment. Response rates were higher in the carboplatin/paclitaxel arm (OR 66 vs 54%, P=0.06) as was the median progression-free survival (12 vs 9 months) and overall survival (29 vs 24 months, HR=0.82, P=0.02).

However, there may be problems in re-treating patients with carboplatin/paclitaxel at relapse when they have received this combination at first line particularly if their treatment-free interval is 6–12 months. These patients frequently have a degree of residual peripheral neuropathy and have only just regained a normal length of hair; repeating and possibly exacerbating the former toxicity in a short space of time is not acceptable to many patients and their physicians, especially since these patients have a rather poor prognosis. Carboplatin/gemcitabine is a treatment option for patients with a potentially platinum-sensitive relapse. In a randomised study conducted by the AGO in 356 patients, the median progression-free survival was 8.6 months for patients treated with carboplatin/gemcitabine and 5.8 months for those receiving single-agent carboplatin, the response rate in the combination arm was 47.2 and 30.9% for carboplatin alone (Pfisterer et al, 2005).

In the context of these different regimens, other combinations such as ECarboX are worthy of consideration. However, toxicity remains a major concern and the question that has to be raised is whether the potential risks outweigh the benefits.

One option would be to omit the anthracycline from the ECarboX regimen. Such an approach is supported by data from the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynaekologische Onkologie (AGO) group trial and the NSGO-EORTC-NCIC CTG gynaecological cancer intergroup trial. These were two large randomised trials of first-line chemotherapy, both of which have shown that the addition of epirubicin to carboplatin/paclitaxel is of no benefit (Kristensen et al, 2003; Du Bois et al, 2004).

The addition of epirubicin to a two-drug combination in the second-line setting may therefore be of doubtful value. Consequently we are currently evaluating the use of carboplatin in combination with capecitabine in a phase-2 trial. This two-drug combination may prove to be a suitable candidate for further randomised trials in relapsed ovarian cancer.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Ahmed FY, King DM, Nicol B, Osborne R, Gallagher C, Harper P, Slevin M, Gore ME (1995) Preliminary results of infusional chemotherapy (cisplatin, epirubicin and 5-fluorouracil, ECF) for refractory and relapsed epithelial ovarian cancer. ASCO Annual Meeting, Abstract No: 790

Boehmer CH, Jaeger W (2002) Capecitabine in treatment of platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer. Anticancer Res 22: 439–443

Cannistra SA (2002) Is there a ‘best’ choice of second-line agent in the treatment of recurrent, potentially platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer? J Clin Oncol 20: 1158–1160

Chollet P, Bensmaine MA, Brienza S, Deloche C, Cure H, Caillet H, Cvitkovic E (1996) Single agent activity of oxaliplatin in heavily pretreated advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Ann Oncol 7: 1065–1070

Dizon DS, Hensley ML, Poynor EA, Sabbatini P, Aghajanian C, Hummer A, Venkatraman E, Spriggs DR (2002) Retrospective analysis of carboplatin and paclitaxel as initial second-line therapy for recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma: application toward a dynamic disease state model of ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 20: 1238–1247

Du Bois A, Combe M, Rochon J, Jackisch C, Malaurie E, Lueck HJ, Loibl S, Schroeder W, Burges A, Weber B (2004) Epirubicin/paclitaxel/carboplatin (TEC) vs paclitaxel/carboplatin (TC) in first-line treatment of ovarian cancer (OC) FIGO stages IIB–IV. An AGO-GINECO Intergroup phase III trial. ASCO Annual Meeting, Abstract No: 5007

Frickhofen N, Beck FJ, Jung B, Fuhr HG, Andrasch H, Sigmund M (2002) Capecitabine can induce acute coronary syndrome similar to 5-fluorouracil. Ann Oncol 13: 797–801

Gordon AN, Fleagle JT, Guthrie D, Parkin DE, Gore ME, Lacave AJ (2001) Recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma: a randomized phase III study of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin versus topotecan. J Clin Oncol 19: 3312–3322

Gordon AN, Tonda M, Sun S, Rackoff W, Doxil Study 30–49 Investigators (2004) Long-term survival advantage for women treated with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin compared with topotecan in a phase 3 randomized study of recurrent and refractory epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 95: 1–8

Gore M, Oza A, Rustin G, Malfetano J, Calvert H, Clarke-Pearson D, Carmichael J, Ross G, Beckman RA, Fields SZ (2002) A randomised trial of oral versus intravenous topotecan in patients with relapsed epithelial ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer 38: 57–63

Greenlee RT, Hill-Harmon MB, Murray T, Thun M (2001) Cancer Statistics, 2001. CA Cancer J Clin 51: 15–36

Havsteen H, Bertelsen K, Gadeberg CC, Jacobsen A, Kamby C, Sandberg E, Sengelov L (1996) A phase 2 study with epirubicin as second-line treatment of patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 63: 210–215

Hoff PM, Ansari R, Batist G, Cox J, Kocha W, Kuperminc M, Maroun J, Walde D, Weaver C, Harrison E, Burger HU, Osterwalder B, Wong AO, Wong R (2001) Comparison of oral capecitabine versus intravenous fluorouracil plus leucovorin as first-line treatment in 605 patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: results of a randomized phase III study. J Clin Oncol 19: 2282–2292

Ishikawa T, Sekiguchi F, Fukase Y, Sawada N, Ishitsuka H (1998) Positive correlation between the efficacy of capecitabine and doxifluridine and the ratio of thymidine phosphorylase to dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase activities in tumors in human cancer xenografts. Cancer Res 58: 685–690

Kaye SB, Piccart M, Aapro M, Francis P, Kavanagh J (1997) Phase II trials of docetaxel (Taxotere) in advanced ovarian cancer – an updated overview. Eur J Cancer 33: 2167–2170

Kose MF, Sufliarsky J, Beslija S, Saip P, Tulunay G, Krejcy K, Minarik T, Fitzthum E, Hayden A, Melemed A (2005) A phase II study of gemcitabine plus carboplatin in platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 96: 374–380

Kristensen GB, Vergote I, Stuart G, Del Campo JM, Kaern J, Lopez AB, Eisenhauer E, Aavall-Lundquist E, Ridderheim M, Havsteen H, Mirza MR, Scheistroen M, Vrdoljak E (2003) First-line treatment of ovarian cancer FIGO stages IIb–IV with paclitaxel/epirubicin/carboplatin versus paclitaxel/carboplatin. Int J Gynecol Cancer 13: 172–177

Muggia FM, Hainsworth JD, Jeffers S, Miller P, Groshen S, Tan M, Roman L, Uziely B, Muderspach L, Garcia A, Burnett A, Greco FA, Morrow CP, Paradiso LJ, Liang LJ (1997) Phase II study of liposomal doxorubicin in refractory ovarian cancer: antitumor activity and toxicity modification by liposomal encapsulation. J Clin Oncol 15: 987–993

Ozols RF (2002) Recurrent ovarian cancer: evidence-based treatment. J Clin Oncol 20: 1161–1163

Ozols RF, Bundy BN, Greer BE, Fowler JM, Clarke-Pearson D, Burger RA, Mannel RS, DeGeest K, Hartenbach EM, Baergen R, Gynecologic Oncology Group (2003) Phase III trial of carboplatin and paclitaxel compared with cisplatin and paclitaxel in patients with optimally resected stage III ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 21: 3194–3200

Parmar MK, Ledermann JA, Colombo N, du Bois A, Delaloye JF, Kristensen GB, Wheeler S, Swart AM, Qian W, Torri V, Floriani I, Jayson G, Lamont A, Trope C, ICON and AGO Collaborators (2003) Paclitaxel plus platinum-based chemotherapy versus conventional platinum-based chemotherapy in women with relapsed ovarian cancer: the ICON4/AGO-OVAR-2.2 trial. Lancet 361: 2099–2106

Pfisterer J, Vergote I, Du Bois A, Eisenhauer E, AGO-OVAR; NCIC CTG; EORTC GCG (2005) Combination therapy with gemcitabine and carboplatin in recurrent ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 15: 36–41

Piccart MJ, Green JA, Lacave AJ, Reed N, Vergote I, Benedetti-Panici P, Bonetti A, Kristeller-Tome V, Fernandez CM, Curran D, Van Glabbeke M, Lacombe D, Pinel MC, Pecorelli S (2000) Oxaliplatin or paclitaxel in patients with platinum-pretreated advanced ovarian cancer: a randomized phase II study of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Gynecology Group. J Clin Oncol 18: 1193–1202

Rischin D, Phillips KA, Friedlander M, Harnett P, Quinn M, Richardson G, Martin A (2004) A phase II trial of capecitabine in heavily pre-treated platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Gynaecol Oncol 93: 417–421

Rose PG, Blessing JA, Mayer AR, Homesley HD (1998) Prolonged oral etoposide as second-line therapy for platinum-resistant and platinum-sensitive ovarian carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 16: 405–410

Schilsky RL (2000) Pharmacology and clinical status of capecitabine. Oncology (Williston Park) 14: 1297–1306

Schnetzler B, Popova N, Collao Lamb C, Sappino AP (2001) Coronary spasm induced by capecitabine. Ann Oncol 12: 723–724

Shapiro JD, Millward MJ, Rischin D, Davison JD, Michael M, Francis PA, Ganju V, Toner GC (1996) Activity of gemcitabine in patients with advanced ovarian cancer: responses seen following platinum and paclitaxel. Gynecol Oncol 63: 89–93

Sorensen P, Hoyer M, Jakobsen A, Malmstrom H, Havsteen H, Bertelsen K (2001) Phase II study of vinorelbine in the treatment of platinum-resistant ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 8: 58–62

Swenerton K, Jeffrey J, Stuart G, Roy M, Krepart G, Carmichael J, Drouin P, Stanimir R, O’Connell G, MacLean G (1992) Cisplatin-cyclophosphamide versus carboplatin-cyclophosphamide in advanced ovarian cancer: a randomized phase III study of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol 10: 718–726

Taylor AE, Wiltshaw E, Gore ME, Fryatt I, Fisher C (1994) Long-term follow-up of the first randomized study of cisplatin versus carboplatin for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 12: 2066–2070

Van Cutsem E, Twelves C, Cassidy J, Allman D, Bajetta E, Boyer M, Bugat R, Findlay M, Frings S, Jahn M, McKendrick J, Osterwalder B, Perez-Manga G, Rosso R, Rougier P, Schmiegel WH, Seitz JF, Thompson P, Vieitez JM, Weitzel C, Harper P, Xeloda Colorectal Cancer Study Group (2001) Oral capecitabine compared with intravenous fluorouracil plus leucovorin in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: results of a large phase III study. J Clin Oncol 19: 4097–4106

Vasey PA, McMahon L, Paul J, Reed N, Kaye SB (2003) A phase II trial of capecitabine (Xeloda) in recurrent ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer 89: 1843–1848

Webb A, A’Hern R, Everard M, Gibbs D, Bomphray C, Gore ME (2000) High activity of epirubicin, cisplatin, protracted venous infusional (PVI) 5-fluoururacil (ECF) after platinum and taxanes in relapsed ovarian cancer (EOC). ASCO Annual Meeting, Abstract No: 1566

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Rothermundt, C., Hubner, R., Ahmad, T. et al. Combination chemotherapy with carboplatin, capecitabine and epirubicin (ECarboX) as second- or third-line treatment in patients with relapsed ovarian cancer: a phase I/II trial. Br J Cancer 94, 74–78 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6602879

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6602879

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A phase I trial of bortezomib in combination with epirubicin, carboplatin and capecitabine (ECarboX) in advanced oesophagogastric adenocarcinoma

Investigational New Drugs (2014)

-

Sensitisation for cisplatin-induced apoptosis by isothiocyanate E-4IB leads to signalling pathways alterations

British Journal of Cancer (2006)