Abstract

Due to their favourable tolerability profiles, endocrine therapies have long been considered the treatment of choice for hormone-sensitive metastatic breast cancer. However, the oestrogen agonist effects of the available selective oestrogen receptor modulators, such as tamoxifen, and the development of cross-resistance between endocrine therapies with similar modes of action have led to the need for new treatments that act through different mechanisms. Fulvestrant (‘Faslodex’) is the first of a new type of endocrine treatment – an oestrogen receptor (ER) antagonist that downregulates the ER and has no agonist effects. This article provides an overview of the current understanding of ER signalling and illustrates the unique mode of action of fulvestrant. Preclinical and clinical study data are presented in support of the novel mechanism of action of this new type of ER antagonist.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

New hormonal therapies with novel mechanisms of action that are not cross-resistant with the existing treatments make important additions to the repertoire of treatments for breast cancer. This enables additional endocrine agents to be used sequentially, with the aim of extending the effective duration of well-tolerated treatment before cytotoxic chemotherapy becomes necessary (Carlson, 2002).

Fulvestrant (‘Faslodex’) is the first of a new type of endocrine treatment – an oestrogen receptor (ER) antagonist that downregulates the ER and has no agonist effects. An understanding of ER signalling is essential to distinguish between the mode of action of fulvestrant and that of tamoxifen and the other selective ER modulators (SERMs). This article summarises the current knowledge of oestrogen signalling, and outlines the mechanism of action of fulvestrant.

Oestrogen signalling as a target for breast cancer therapy

17β-oestradiol, the dominant circulating oestrogen, controls the growth of many breast tumours. Oestradiol is secreted by the ovaries in premenopausal women, but is also present at significant levels in postmenopausal breast tumours. In postmenopausal women, oestrogens are produced by aromatase-mediated conversion of androgens (originating from the adrenal glands and the ovaries) to oestrogens, in normal tissues (adipose tissue, muscle, liver, or brain) as well as in breast tumours (Buzdar, 2001).

The ER is expressed in the majority of breast tumours (Jonat and Maass, 1978; Lee and Markland, 1978; Paszko et al, 1978) and in a number of endocrine tissues including the normal breast, uterus and vagina, as well as in the pituitary and hypothalamus.

Oestradiol binds to the ER with a high affinity and specificity and, once bound, the oestradiol/ER complex can exert its effects at both nuclear and cell membranous sites (Figure 1). In the classical nuclear ER pathway of transcriptional control, the binding of oestradiol to the ER initiates dissociation of heat shock proteins from the ER, followed by receptor dimerisation and preferential nuclear localisation (Beato, 1989; MacGregor and Jordan, 1998).

The oestrogen–ER dimer complex binds to specific DNA sequences, the oestrogen response elements (EREs), which are situated in the regulatory regions of oestrogen-sensitive genes. Transcriptional control is mediated via two regions of the ER-designated activation functions AF1 and AF2, which recruit other proteins such as transcriptional co-activators and co-repressors to the transcriptional complex (Beato, 1989; Tsai and O'Malley, 1994; Horwitz et al, 1996; White and Parker, 1998). AF1 activity is regulated by growth factors that act via the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway (Kato et al, 1995), while the AF2 domain is activated by oestrogen (Kumar et al, 1987). Both domains are required to be active for full oestrogen agonist activity. The ER mediates transcriptional regulation of a range of genes, directly or indirectly associated with proliferation, invasion, survival or angiogenesis in breast cancer.

To date, two ERs have been identified: the ‘classic’ ERα and the relatively more recently described ERβ (Kuiper et al, 1996). These two ER subtypes have different tissue distributions (Speirs et al, 2002), different affinities and responsiveness to various SERMs (Ogawa et al, 1998), and are under different regulatory control (Katzenellenbogen and Katzenellenbogen, 2000). Oestrogen receptorα rather than ERβ appears to be the predominant regulator of oestrogen-induced genes in breast cancer (Palmieri et al, 2002; Fuqua et al, 2003).

In addition to the classical ER signalling pathway, the ER can also undergo ‘crosstalk’ with growth factor and G-protein-coupled signalling pathways (Philips et al, 1993; Losel and Wehling, 2003) (Figure 1). For example, oestrogen can activate membrane-bound ER and, via G-protein activation, can then activate growth factor receptors such as the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2/neu) (Filardo, 2002; Johnston et al, 2003). In turn, the ER itself may be activated in a ligand-independent manner by other signalling molecules such as growth factors and protein kinases that control the phosphorylation state of the ER complex and play a part in regulating activity of the ER (Katzenellenbogen et al, 2000).

The need for alternative endocrine therapies

In patients with hormone-sensitive advanced breast cancer, endocrine therapy is better tolerated than cytotoxic chemotherapy, while being equally effective (Buzdar, 2001). However, there are specific risks associated with endocrine treatments. For example, tamoxifen treatment is associated with a 2–4-fold increased risk of endometrial cancer (Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group, 1998), attributable to its oestrogen-like, partial agonist activity. The ‘Arimidex’, Tamoxifen Alone or in Combination (ATAC) trial showed a significantly greater incidence of ischaemic cerebrovascular events (2.1 vs 1.0%; P=0.0006) and venous thromboembolic events (3.5 vs 2.1%; P=0.0006) with tamoxifen, compared with the aromatase inhibitor (AI) anastrozole (ATAC Trialists' Group, 2002). A number of other antioestrogens grouped together under the term SERMS have also been associated with partial agonist properties (Johnston, 2001; Arun et al, 2002).

The AIs letrozole and exemestane may have an unfavourable effect on plasma lipid levels, and androgenic side effects have been reported with exemestane (Buzdar, 2003). Megestrol acetate, historically the most widely used progestin, is associated with weight gain and fluid retention (Espie, 1994) and the high-dose oestrogen diethylstilboestrol is commonly associated with nausea, oedema, vaginal bleeding and cardiac problems (Peethambaram et al, 1999).

The sequential use of well-tolerated hormonal therapies has become common clinical practice for the treatment of advanced breast cancer, where maintenance of quality of life is a primary aim. For this to be effective, it is necessary that the mechanism of action of newer agents differ from those previously used. This prerequisite prevents the sequential use of therapies belonging to the same class, and that therefore demonstrates cross-resistance with each other. Therefore, for some time, a search has been under way for an antioestrogen that lacks partial agonist properties and that has a mechanism of action different from tamoxifen (Wakeling and Bowler, 1988).

Fulvestrant: A potent er antagonist with a novel mechanism of action

Blockade of oestrogen action via ER antagonism

Fulvestrant is a 7α-alkylsulphinyl analogue of 17β-oestradiol, which is distinctly different in chemical structure from the nonsteroidal structures of tamoxifen, raloxifene and other SERMs (Figure 2). Fulvestrant competitively inhibits binding of oestradiol to the ER, with a binding affinity that is 89% that of oestradiol (Wakeling and Bowler, 1987). This is markedly greater than the affinity of tamoxifen for the ER (which is 2.5% that of oestradiol) (Wakeling and Bowler, 1987; Wakeling et al, 1991).

Fulvestrant–ER binding impairs receptor dimerisation, and energy-dependent nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling, thereby blocking nuclear localisation of the receptor (Fawell et al, 1990; Dauvois et al, 1993) (Figure 3). Additionally, any fulvestrant–ER complex that enters the nucleus is transcriptionally inactive because both AF1 and AF2 are disabled. Finally, the fulvestrant–ER complex is unstable, resulting in accelerated degradation of the ER protein, compared with oestradiol- or tamoxifen-bound ER (Nicholson et al, 1995b). This downregulation of cellular ER protein occurs without a reduction in ER mRNA. Thus, fulvestrant binds, blocks and accelerates degradation of ER protein, leading to complete inhibition of oestrogen signalling through the ER (Osborne et al, 1995; Wakeling, 1995,2000; Wardley, 2002).

Fulvestrant has no demonstrable agonist activity

The disruption of both AF1 and AF2 sites means that, in contrast to the SERMs such as tamoxifen which fail to inhibit AF1 activity and thereby have partial oestrogen agonist activity, fulvestrant has no oestrogen agonist activity in animals or man. This lack of agonist activity has been demonstrated in numerous animal models of oestrogen action. Thus, in immature female rats, fulvestrant, unlike tamoxifen, was completely devoid of uterotrophic activity. Correspondingly, co-administration of fulvestrant with either oestradiol or tamoxifen blocked the maximal and partial uterotrophic activity of oestradiol or tamoxifen, respectively, in a dose-dependent and complete manner (Wakeling et al, 1991). In contrast, co-administration of tamoxifen and oestradiol only partially blocks the uterotrophic action of oestradiol. In primate studies, fulvestrant inhibited oestradiol-induced increases in the volume of the endometrium; the rate and extent of endometrial involution in fulvestrant-treated monkeys was similar to that seen following oestrogen withdrawal (Dukes et al, 1992). In a Phase I trial involving 30 postmenopausal volunteers, fulvestrant 250 mg (intramuscular (i.m.) injection) demonstrated no agonist effects on the human endometrium during the 14-day period of administration. In addition, the antagonistic effects of fulvestrant were confirmed by a significant inhibition of the oestrogen-stimulated thickening of the endometrium compared with placebo (P=0.0001) (Addo et al, 2002).

Biological effects and lack of cross-resistance with tamoxifen

Preclinical antitumour activity and effects on ER signalling

Studies in the MCF-7 human breast cancer cell line have shown that fulvestrant significantly suppresses cellular levels of ER protein (McClelland et al, 1996a) and inhibits ER-induced expression of the progesterone receptor (PgR), the oestrogen-regulated protein pS2 and cathepsin D more strongly than tamoxifen (Nicholson et al, 1995a). In a study of global gene expression in MCF-7 cells, after supplemental oestrogen, a subset of ER-responsive genes upregulated by oestrogen were selected, and the effects of fulvestrant and tamoxifen were analysed by microarray expression profiling and Northern blot analysis (Inoue et al, 2002). For most of these genes, oestrogen-regulated expression was completely abolished by fulvestrant. In contrast, in the presence of tamoxifen, some genes remained, in part, transcriptionally responsive to oestrogen (Inoue et al, 2002). Similarly, in MCF-7 tumour xenografts, fulvestrant has also been shown to be more effective than tamoxifen in reducing cellular levels of the ER and PgR; expression levels of other oestrogen-regulated genes pLIV1 and pS2 were also greatly reduced (Osborne et al, 1994,Osborne et al, 1994, 1995).

Fulvestrant also blocks ER-mediated effects in the MCF-7 cell line by decreasing the levels of transforming growth factor α (TGFα), thereby reducing ‘crosstalk’ between these pathways (Nicholson et al, 1995a). Furthermore, in rat adipocytes, physiological concentrations (0.1–10 nM) of oestrogen have been shown to rapidly activate the p42/p44 MAPK independently of transcriptional activation. This effect is also blocked by fulvestrant (Dos Santos et al, 2002).

Fulvestrant is a more effective growth inhibitor of ER-positive MCF-7 human breast cancer cells than tamoxifen, producing an 80% reduction in cell numbers under conditions where tamoxifen achieved a maximum of 50% inhibition (Wakeling and Bowler, 1987). Flow cytometry of MCF-7 cells showed fulvestrant to be more effective than tamoxifen in increasing the proportion of cells in G0/G1 and decreasing the proportion of cells capable of continued DNA synthesis (Wakeling and Bowler, 1987; Wakeling et al, 1991). Importantly, fulvestrant has also demonstrated antitumour activity in tamoxifen-resistant MCF-7/TAMR−1 cell lines, confirming a lack of cross-resistance between tamoxifen and fulvestrant (Hu et al, 1993; Lykkesfeldt et al, 1994). At fulvestrant concentrations of 5–10 nmol l−1, cell growth of tamoxifen-resistant MCF-7 cells was completely inhibited. Compared with tamoxifen, fulvestrant was 150 times more effective at inhibiting cell growth in the tamoxifen-sensitive parental line, and 1540 times more effective in the tamoxifen-resistant variant cell line (Hu et al, 1993). Furthermore, in later preclinical studies, fulvestrant-resistant MCF-7 cells demonstrated no resistance to tamoxifen, with sensitivity similar to that of the parental cell line (Lykkesfeldt et al, 1995).

In vivo, the antitumour activity of fulvestrant was first demonstrated in two models of human breast cancer in nude mice. In one of these models, the growth of MCF-7 tumour xenografts, supported by continuous treatment with oestradiol, was completely blocked for at least 4 weeks following a single injection of fulvestrant 5 mg (Osborne et al, 1995). Similar reductions in growth were seen in the Br10 human tumour model (Wakeling et al, 1991). In other studies in nude mice bearing MCF-7 xenografts, fulvestrant suppressed the growth of established tumours for twice as long and tumour growth was delayed to a greater extent than was observed with tamoxifen treatment. Tamoxifen-resistant breast tumours, which grew in nude mice after long-term treatment with tamoxifen, remained sensitive to growth inhibition by fulvestrant (Osborne et al, 1994).

Antitumour activity and effects on ER signalling in patients with breast cancer

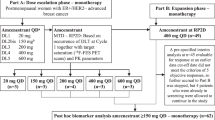

The biological and antitumour effects of fulvestrant have also been evaluated in several trials involving postmenopausal women with primary breast cancer. The effects of daily i.m. injections of short-acting fulvestrant (either 6 or 18 mg) for 7 days prior to surgery for primary breast cancer were compared with no pretreatment controls in 56 postmenopausal women (DeFriend et al, 1994). In patients with ER-positive (ER+) tumours (28/56), fulvestrant caused a significant reduction in median ER index (0.73 vs 0.02 pre- and post-treatment, respectively; P<0.001) and almost abolished PgR expression; the median PgR index was reduced from 0.50 to 0.01 post-treatment (P<0.05; n=37) in ER+ tumours. This reduction in cellular ER protein occurred without a concurrent reduction in ER mRNA levels (McClelland et al, 1996b). Fulvestrant caused a significant reduction in pS2 expression and tumour proliferation. pS2 expression was reduced from 7 to 1% after treatment (P<0.05; n=37) and the proliferation marker Ki67 was reduced from 3.2 to 1.1% following fulvestrant treatment (P<0.05) (DeFriend et al, 1994).

In a subsequent study that compared the effects of a single dose of long-acting fulvestrant (50, 125, or 250 mg), continuous daily tamoxifen, or placebo for 14–21 days in patients with primary breast tumours, all fulvestrant doses produced statistically significant reductions in ER expression compared with placebo (50 mg: 32% reduction, P=0.026; 125 mg: 55% reduction, P=0.0006; 250 mg: 72% reduction, P=0.0001). At the higher 250 mg dose, the fulvestrant-induced reduction was significantly greater than that observed with tamoxifen (P=0.024) (Robertson et al, 2001). Significant reductions in PgR expression were also observed at the fulvestrant 125 mg (P=0.003) and 250 mg (P=0.0002) doses compared with placebo. In contrast, tamoxifen resulted in a significant increase in PgR expression relative to placebo, a finding attributed to its partial agonist effects and further emphasising the differences in mode of action between fulvestrant and tamoxifen (Robertson et al, 2001) (Figure 4).

Mean (A) ER and (B) PgR levels after a single i.m. injection of 50, 125, or 250 mg fulvestrant, 20 mg tamoxifen, or placebo. Reproduced with the permission of Cancer Research (Robertson et al, 2001).

Fulvestrant produced significant dose-dependent reductions in Ki67 compared with placebo (50 mg: P=0.046; 125 mg: P=0.001; 250 mg: P=0.0002), although there were no differences in Ki67 between fulvestrant and tamoxifen (Robertson et al, 2001). The cell turnover index (CTI) is a composite measurement of both cell proliferation and apoptosis, and provides a useful indicator of drug action on breast tumour growth. In the same study, patients receiving fulvestrant 250 mg showed a significant reduction in the CTI compared with those who received placebo (P=0.0003) and tamoxifen (P=0.026). The effect on CTI with tamoxifen was not significantly different from that with placebo (Bundred et al, 2002).

Taken together with the preclinical data, these findings emphasise the differences in mode of action and the lack of cross-resistance between the SERMs and fulvestrant, which has latterly been supported by phase III data, demonstrating the efficacy of fulvestrant in patients with tamoxifen-resistant disease.

Conclusions

Fulvestrant is a new type of endocrine treatment – an ER antagonist with a novel mode of action. Fulvestrant disrupts ER dimerisation and nuclear localisation, completely blocking ER-mediated transcriptional activity and accelerating receptor degradation. Consequently, fulvestrant also blocks the activity of oestrogen-regulated genes associated with breast tumour progression, invasion, metastasis and angiogenesis. The antitumour effects of fulvestrant have been demonstrated both in preclinical studies and in clinical trials, using a number of prognostic and predictive markers. This new type of endocrine therapy has no oestrogen agonist effects, and lacks cross-resistance with other antioestrogens. Antioestrogens with novel mechanisms of action such as fulvestrant represent a valuable second-line treatment option for postmenopausal women with hormone-sensitive advanced breast cancer, who have progressed on prior tamoxifen therapy. Fulvestrant and other new endocrine therapies may also provide opportunities for a longer treatment period with well-tolerated endocrine therapy before the need for cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Addo S, Yates RA, Laight A (2002) A phase I trial to assess the pharmacology of the new oestrogen receptor antagonist fulvestrant on the endometrium in healthy postmenopausal volunteers. Br J Cancer 87: 1354–1359

Arun B, Anthony M, Dunn B (2002) The search for the ideal SERM. Expert Opin Pharmacother 3: 681–691

ATAC Trialists' Group (2002) Anastrozole alone or in combination with tamoxifen versus tamoxifen alone for adjuvant treatment of postmenopausal women with early breast cancer: first results of the ATAC randomised trial. Lancet 359: 2131–2139

Beato M (1989) Gene regulation by steroid hormones. Cell 56: 335–344

Bundred NJ, Anderson E, Nicholson RI, Dowsett M, Dixon M, Robertson JF (2002) Fulvestrant, an estrogen receptor downregulator, reduces cell turnover index more effectively than tamoxifen. Anticancer Res 22: 2317–2319

Buzdar AU (2001) Endocrine therapy in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Semin Oncol 28: 291–304

Buzdar AU (2003) Pharmacology and pharmacokinetics of the newer generation aromatase inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res 9: 468S–472S

Carlson RW (2002) Sequencing of endocrine therapies in breast cancer – integration of recent data. Breast Cancer Res Treat 75(Suppl 1): S27–S32

Dauvois S, White R, Parker MG (1993) The antiestrogen ICI 182780 disrupts estrogen receptor nucleocytoplasmic shuttling. J Cell Sci 106 (Part 4): 1377–1388

DeFriend DJ, Howell A, Nicholson RI, Anderson E, Dowsett M, Mansel RE, Blamey RW, Bundred NJ, Robertson JF, Saunders C, Baum M, Walton P, Sutcliffe F, Wakeling AE (1994) Investigation of a new pure antiestrogen (ICI 182780) in women with primary breast cancer. Cancer Res 54: 408–414

Dos Santos EG, Dieudonne MN, Pecquery R, Le Moal V, Giudicelli Y, Lacasa D (2002) Rapid nongenomic E2 effects on p42/p44 MAPK, activator protein-1, and cAMP response element binding protein in rat white adipocytes. Endocrinology 143: 930–940

Dukes M, Miller D, Wakeling AE, Waterton JC (1992) Antiuterotrophic effects of a pure antioestrogen, ICI 182,780: magnetic resonance imaging of the uterus in ovariectomized monkeys. J Endocrinol 135: 239–247

Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (1998) Tamoxifen for early breast cancer: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 351: 1451–1467

Espie M (1994) Megestrol acetate in advanced breast carcinoma. Oncology 51(Suppl 1): 8–12

Fawell SE, White R, Hoare S, Sydenham M, Page M, Parker MG (1990) Inhibition of estrogen receptor-DNA binding by the ‘pure’ antiestrogen ICI 164,384 appears to be mediated by impaired receptor dimerization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87: 6883–6887

Filardo EJ (2002) Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) transactivation by estrogen via the G-protein-coupled receptor, GPR30: a novel signaling pathway with potential significance for breast cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 80: 231–238

Fuqua SA, Schiff R, Parra I, Moore JT, Mohsin SK, Osborne CK, Clark GM, Allred DC (2003) Estrogen receptor beta protein in human breast cancer: correlation with clinical tumor parameters. Cancer Res 63: 2434–2439

Horwitz KB, Jackson TA, Bain DL, Richer JK, Takimoto GS, Tung L (1996) Nuclear receptor coactivators and corepressors. Mol Endocrinol 10: 1167–1177

Hu XF, Veroni M, De Luise M, Wakeling A, Sutherland R, Watts CK, Zalcberg JR (1993) Circumvention of tamoxifen resistance by the pure anti-estrogen ICI 182,780. Int J Cancer 55: 873–876

Inoue A, Yoshida N, Omoto Y, Oguchi S, Yamori T, Kiyama R, Hayashi S (2002) Development of cDNA microarray for expression profiling of estrogen-responsive genes. J Mol Endocrinol 29: 175–192

Johnston SR (2001) Endocrine manipulation in advanced breast cancer: recent advances with SERM therapies. Clin Cancer Res 7: 4376s–4387s

Johnston SR, Head J, Pancholi S, Detre S, Martin L, Smith IE, Dowsett M (2003) Integration of signal transduction inhibitors with endocrine therapy: an approach to overcoming hormone resistance in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 9: 524S–532S

Jonat W, Maass H (1978) Some comments on the necessity of receptor determination in human breast cancer. Cancer Res 38: 4305–4306

Kato S, Endoh H, Masuhiro Y, Kitamoto T, Uchiyama S, Sasaki H, Masushige S, Gotoh Y, Nishida E, Kawashima H (1995) Activation of the estrogen receptor through phosphorylation by mitogen-activated protein kinase. Science 270: 1491–1494

Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA (2000) Estrogen receptor transcription and transactivation: estrogen receptor alpha and estrogen receptor beta: regulation by selective estrogen receptor modulators and importance in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 2: 335–344

Katzenellenbogen BS, Montano MM, Ediger TR, Sun J, Ekena K, Lazennec G, Martini PG, McInerney EM, Delage-Mourroux R, Weis K, Katzenellenbogen JA (2000) Estrogen receptors: selective ligands, partners, and distinctive pharmacology. Recent Prog Horm Res 55: 163–193

Kuiper GG, Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Nilsson S, Gustafsson JA (1996) Cloning of a novel receptor expressed in rat prostate and ovary. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 5925–5930

Kumar V, Green S, Stack G, Berry M, Jin JR, Chambon P (1987) Functional domains of the human estrogen receptor. Cell 51: 941–951

Lee YT, Markland FS (1978) Steroid receptors study in breast carcinoma. Med Pediatr Oncol 5: 153–166

Losel R, Wehling M (2003) Nongenomic actions of steroid hormones. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4: 46–56

Lykkesfeldt AE, Larsen SS, Briand P (1995) Human breast cancer cell lines resistant to pure anti-estrogens are sensitive to tamoxifen treatment. Int J Cancer 61: 529–534

Lykkesfeldt AE, Madsen MW, Briand P (1994) Altered expression of estrogen-regulated genes in a tamoxifen-resistant and ICI 164,384 and ICI 182,780 sensitive human breast cancer cell line, MCF-7/TAMR-1. Cancer Res 54: 1587–1595

MacGregor JI, Jordan VC (1998) Basic guide to the mechanisms of antiestrogen action. Pharmacol Rev 50: 151–196

McClelland RA, Gee JM, Francis AB, Robertson JF, Blamey RW, Wakeling AE, Nicholson RI (1996a) Short-term effects of pure anti-oestrogen ICI 182780 treatment on oestrogen receptor, epidermal growth factor receptor and transforming growth factor-alpha protein expression in human breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 32A: 413–416

McClelland RA, Manning DL, Gee JM, Anderson E, Clarke R, Howell A, Dowsett M, Robertson JF, Blamey RW, Wakeling AE, Nicholson RI (1996b) Effects of short-term antiestrogen treatment of primary breast cancer on estrogen receptor mRNA and protein expression and on estrogen-regulated genes. Breast Cancer Res Treat 41: 31–41

Nicholson RI, Gee JM, Francis AB, Manning DL, Wakeling AE, Katzenellenbogen BS (1995a) Observations arising from the use of pure antioestrogens on oestrogen-responsive (MCF-7) and oestrogen growth-independent (K3) human breast cancer cells. Endocr Relat Cancer 2: 115–121

Nicholson RI, Gee JM, Manning DL, Wakeling AE, Montano MM, Katzenellenbogen BS (1995b) Responses to pure antiestrogens (ICI 164384, ICI 182780) in estrogen-sensitive and -resistant experimental and clinical breast cancer. Ann NY Acad Sci 761: 148–163

Ogawa S, Inoue S, Watanabe T, Orimo A, Hosoi T, Ouchi Y, Muramatsu M (1998) Molecular cloning and characterization of human estrogen receptor betacx: a potential inhibitor of estrogen action in human. Nucleic Acids Res 26: 3505–3512

Osborne CK, Coronado-Heinsohn EB, Hilsenbeck SG, McCue BL, Wakeling AE, McClelland RA, Manning DL, Nicholson RI (1995) Comparison of the effects of a pure steroidal antiestrogen with those of tamoxifen in a model of human breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 87: 746–750

Osborne CK, Jarman M, McCague R, Coronado EB, Hilsenbeck SG, Wakeling AE (1994) The importance of tamoxifen metabolism in tamoxifen-stimulated breast tumor growth. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 34: 89–95

Palmieri C, Cheng GJ, Saji S, Zelada-Hedman M, Warri A, Weihua Z, Van Noorden S, Wahlstrom T, Coombes RC, Warner M, Gustafsson JA (2002) Estrogen receptor beta in breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 9: 1–13

Paszko Z, Padzik K, Dabska M, Pienkowska F (1978) Estrogen receptor in human breast cancer in relation to tumor morphology and endocrine therapy. Tumori 64: 495–506

Peethambaram PP, Ingle JN, Suman VJ, Hartmann LC, Loprinzi CL (1999) Randomized trial of diethylstilbestrol vs tamoxifen in postmenopausal women with metastatic breast cancer. An updated analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 54: 117–122

Philips A, Chalbos D, Rochefort H (1993) Estradiol increases and anti-estrogens antagonize the growth factor-induced activator protein-1 activity in MCF7 breast cancer cells without affecting c-fos and c-jun synthesis. J Biol Chem 268: 14103–14108

Robertson JF, Nicholson RI, Bundred NJ, Anderson E, Rayter Z, Dowsett M, Fox JN, Gee JM, Webster A, Wakeling AE, Morris C, Dixon M (2001) Comparison of the short-term biological effects of 7alpha-[9-(4,4,5,5,5-pentafluoropentylsulfinyl)-nonyl]estra-1,3,5, (10)-triene-3,17beta-diol (Faslodex) versus tamoxifen in postmenopausal women with primary breast cancer. Cancer Res 61: 6739–6746

Speirs V, Skliris GP, Burdall SE, Carder PJ (2002) Distinct expression patterns of ER alpha and ER beta in normal human mammary gland. J Clin Pathol 55: 371–374

Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW (1994) Molecular mechanisms of action of steroid/thyroid receptor superfamily members. Annu Rev Biochem 63: 451–486

Wakeling AE (1995) Use of pure antioestrogens to elucidate the mode of action of oestrogens. Biochem Pharmacol 49: 1545–1549

Wakeling AE (2000) Similarities and distinctions in the mode of action of different classes of antioestrogens. Endocr Relat Cancer 7: 17–28

Wakeling AE, Bowler J (1987) Steroidal pure antioestrogens. J Endocrinol 112: R7–R10

Wakeling AE, Bowler J (1988) Novel antioestrogens without partial agonist activity. J Steroid Biochem 31: 645–653

Wakeling AE, Dukes M, Bowler J (1991) A potent specific pure antiestrogen with clinical potential. Cancer Res 51: 3867–3873

Wardley AM (2002) Fulvestrant: a review of its development, pre-clinical and clinical data. Int J Clin Pract 56: 305–309

White R, Parker MG (1998) Molecular mechanisms of steroid hormone action. Endocr Relat Cancer 5: 1–14

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Osborne, C., Wakeling, A. & Nicholson, R. Fulvestrant: an oestrogen receptor antagonist with a novel mechanism of action. Br J Cancer 90 (Suppl 1), S2–S6 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6601629

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6601629

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

PROTAC’ing oncoproteins: targeted protein degradation for cancer therapy

Molecular Cancer (2023)

-

Novel Estrogen Receptor-Targeted Agents for Breast Cancer

Current Treatment Options in Oncology (2023)

-

An overview of PROTACs: a promising drug discovery paradigm

Molecular Biomedicine (2022)

-

Estrogen receptor positive breast cancers have patient specific hormone sensitivities and rely on progesterone receptor

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Molecular glues: enhanced protein-protein interactions and cell proteome editing

Medicinal Chemistry Research (2022)