Abstract

Body surface area-dosing does not account for the complex processes of cytotoxic drug elimination. This leads to an unpredictable variation in effect. Overdosing is easily recognised but it is possible that unrecognised underdosing is more common and may occur in 30% or more of patients receiving standard regimen. Those patients who are inadvertently underdosed are at risk of a significantly reduced anticancer effect. Using published data, it can be calculated that there is an almost 20% relative reduction in survival for women receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer as a result of unrecognised underdosing. Similarly, the cure rate of cisplatin-based chemotherapy for advanced testicular cancer may be reduced by as much as 10%. The inaccuracy of body surface area-dosing is more than an inconvenience and it is important that methods for more accurate dose calculation are determined, based on the known drug elimination processes for cytotoxic chemotherapy. Twelve rules for dose calculation of chemotherapy are given that can be used as a guideline until better dose-calculation methods become available. Consideration should be given to using fixed dose guidelines independent of body surface area and based on drug elimination capability, both as a starting dose and for dose adjustment, which may have accuracy, safety and financial advantages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Despite the recent advances in anticancer treatment and the promise of novel targeted therapies, it is likely that cytotoxic chemotherapy will continue to be used for the next few decades. It is now recognised that our current method of dose calculation for chemotherapy using body surface area (BSA) is inaccurate (Gurney, 1996, 1998; Ratain, 1998). This method does not account for the marked interpatient variation in drug handling that is known to exist for these drugs so that drug effects such as toxicity are also highly variable and therefore unpredictable. One consequence is unexpected underdosing which leads to reduced effectiveness of chemotherapy. However, until there is a better method, BSA-dosing will prevail since there has been over 40 years of experience with this method and ‘old habits die hard’. The following discussion will remind the clinician of the inaccuracies of this system and will suggest guidelines for dose calculation that encourages consideration of important parameters other than BSA alone.

To calculate dose accurately drug elimination needs to be understood. Typically there is a 4–10-fold variation in cytotoxic drug clearance between individuals due to differing activity of drug elimination processes related to genetic and environmental factors (Gurney, 1996). For example, the activity of cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4/5, the major oxidising enzymes for many cytotoxic drugs varies by as much as 50-fold (Wrighton et al, 1996). A common single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) or CYP3A5 has recently been identified and others are being searched for (Kuehl et al, 2001). In addition many drugs and disease states are known to inhibit or induce CYP activity further adding to this variation (George et al, 1996). Another example is the eight-fold variation in dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD) activity, the enzyme that catabolises 5FU (Etienne et al, 1994). Less is known about the variation in other critical hepatic elimination processes such as active biliary excretion by multidrug resistance gene 1 (MDR1), multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (MRP2) and the other ATP binding cassette (ABC) family of efflux pumps, although some polymorphisms have been identified (Tanabe et al, 2001). A number of SNPs have also recently been identified for the steroid and xenbiotic receptor (SXR), a common-pathway receptor which transcriptionally activates a number of the drug elimination genes such as CYP3A4, MRP2 and MDR1 (Zhang et al, 2001). Variation in renal function is more easily identified but none of these complex processes are accounted for when BSA alone is used to calculate drug dose.

The problem of underdosing

It is clear that for most cancers there is a plateau in the dose–response curve for cytotoxic chemotherapy. Increasing the dose above a standard dose will increase toxicity, but does not improve anti-tumour effect (Gurney et al, 1993; Stadtmauer et al, 2000). High-dose chemotherapy is now largely reserved for acute leukaemia and aggressive lymphomas in relapse. However, the dose intensity studies from the last two decades have shown that anti cancer effect is substantially reduced if the dose of drug is intentionally decreased below the standard. What has not been recognised is that a significant proportion of patients may be inadvertently underdosed because of our inaccurate dose–calculation methods, which may cause a reduced cure or other effect.

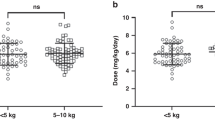

The dose of a new drug is conventionally determined in a phase I study and then adjusted after more widespread use. The end point of this process is prevention of toxicity rather than identifying the dose for best anti-tumour effect. One consequence of this, coupled with the inaccuracy of BSA-dosing, is that significant underdosing becomes intrinsic to our system of dose determination. Figure 1 illustrates the scheme of a phase I study for a drug with linear pharmacokinetics. The horizontal lines represent the variation in systemic exposure at various dose levels. At dose level 3, those patients with lower drug elimination capability develop dose-limiting toxicity and subsequently that dose level is defined as the maximum tolerated dose. Dose level 2 is recommended for phase II studies since it causes tolerable toxicity in all patients. However, due to the variation in drug handling, a proportion of patients will be relatively underdosed since they are more capable of eliminating the drug. This means the wide distribution of systemic exposure is skewed towards the ineffective range when dose is calculated using BSA. Evidence for this effect can be found in a recent study by Gaemelin et al (1999). This group had defined the optimum 5FU plasma concentration with a regimen using 5FU in a dose of 1300 mg m2 infused over 8 h every week. For a group of 81 patients treated with dose calculated using BSA, 80% of patients were found to have an ineffective 5FU plasma concentration after the first dose.

Hypothetical phase I study of a drug with linear pharmacokinetics. Horizontal bars represent interpatient variation in systemic exposure. Each vertical tick mark represents an individual patient on the study. Dose level 3 would be considered the MTD and dose level 2 would be recommended for phase II study despite the majority of patients on that dose level having a systemic exposure in the sub-therapeutic range.

What other evidence is available to indicate that underdosing occurs with the current dose calculation method? Here the problem is in defining and identifying underdosing. Can the lack of effect on normal tissue (i.e. toxicity) be used to identify a lack of effect in neoplastic tissue? For this to be tenable a toxicity-response relationship must be shown for cytotoxic chemotherapy. There is a wealth of information regarding dose–toxicity and dose–response relationships but very little information is available in the literature examining the relationship between toxicity and response (Gurney et al, 1993). Three studies from the 1970s and 80s purport a relationship between lack of myelosuppression and lack of anti-tumour effect in osteosarcoma and multiple myeloma (Cortes et al, 1974; McIntyre et al, 1978; Carpenter et al, 1982). However, a firm relationship cannot be claimed given the low patient numbers and the technique of analysis of these studies.

More recently, some studies have illustrated a toxicity-response relationship for breast cancer, testis cancer, ovarian cancer and lymphoma (Table 1) (Rankin et al, 1992; Horwich et al, 1997; Poikenen et al, 1999). A randomised MRC study of combination chemotherapy in advanced testicular cancer showed a significantly higher relapse rate in patients receiving carboplatin who failed to develop myelosuppression. There was a similar relationship shown for patients receiving cisplatin. Relapse rate for the cisplatin containing regimen was 11% for patients with a nadir white cell count (WCC) of over 2.0 × 109 per litre compared with 4% for patients whose WCC fell below 2.0 × 109 per litre after chemotherapy. Although this difference was not statistically significant, inadvertent underdosing may be an issue for cisplatin as well as carboplatin-containing regimen in the treatment of testicular cancer. These studies show a significantly worse anti-tumour effect for those patients who failed to develop myelosuppression after treatment compared to those who did. It is important that this relationship is examined more fully in other cancer types. This can be done by re-analysis of previous studies where nadir blood counts have been recorded in the majority of patients. A recent randomised study by the Australian Lymphoma and Leukaemia Group comparing high dose cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, vincristine and prednisolone (CEOP) with standard dose CEOP, showed that those patients who did not experience a nadir neutrophil count of <1.0 × 109 per litre, had a statistically inferior progression free survival (Gurney et al, manuscript in preparation).

If lack of myelosuppression is accepted as an indication of underdosing, the frequency of this event can then be determined. Table 2 is a selection of trials where the frequency and timing of nadir blood counts have been adequately recorded. A substantial percentage of patients (30 to 75%) receiving commonly used chemotherapy regimen have ‘inadequate’ myelosuppression and may be underdosed.

The significance of underdosing

The possible significance of the underdosing is outlined in Table 3. Calculation of published data from studies using adjuvant cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin and 5FU (CAF) for node positive breast cancer show that BSA-based dosing may lead to almost a 20% relative reduction in survival in this setting (Budman et al, 1998; Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group, 1998; Silber et al, 1998). This impact is equivalent to the benefit from the use of adjuvant chemotherapy in node negative breast cancer, or the addition of paclitaxel to the CAF regimen in node positive breast cancer. Similarly, BSA-based dosing may reduce the cure rate of intermediate prognosis testis cancer by almost 10% compared to a dosing method that prevents underdosing (Samson et al, 1984; Horwich et al, 1997). Clearly, if these calculations are accurate, we can no longer tolerate the inaccuracies of BSA dosing as of minor consequence. It is important that more accurate calculation methods are developed. Another obvious bonus of an accurate dose calculation scheme is prevention of toxicity from overdosing.

Prevention of underdosing

One popular method of dose individualisation is to adjust subsequent doses of chemotherapy based on the level of myelosuppression eventually avoiding overdosing and underdosing – so called ‘toxicity-adjusting dosing’ (Gurney, 1996). A Swedish group has adopted this approach in the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer (Berch et al, 2000). Using the 5FU, epirubicin and cyclophosphamide (FEC) regimen, dose adjustments were made on each cycle to ensure a target level of myelosuppression. After a number of dose adjustments this method of individualising dose gave a three-fold interpatient range of cyclophosphamide dose (450 to 1800 mg m2) and a four-fold range for epirubicin (38 to 120 mg m2). This is more in keeping with the known interpatient variation in drug clearance for these drugs. However, it would be better to achieve an individualised dose variation from the first dose rather than the third, fourth or fifth dose. To achieve this, the dose calculation method must take into account the activity of the elimination processes for the drug(s) in question before the first treatment is given.

Fixed dose?

Until better dose calculation methods are determined most clinicians will continue with the traditional method using BSA. However, clinicians should be mindful of the inaccuracies of this system and should not be duped by its pseudo-scientific use of formulas and slide rules. Doses should be rounded liberally. Fractional doses are irrelevant and unnecessary. Furthermore they are expensive and possibly unsafe. It is unreasonable to use a small portion of an extra vial of chemotherapy if the dose prescribe is inaccurate 40% of the time. Ask your pharmacist whether he/she can really draw up 215 mg of DTIC (instead of 200 or 220 mg), 85 mg of docetaxel (instead of 80 or 90 mg) or 63 mg of methotrexate. What is the additional cost of prescribing 305 mg of paclitaxel instead of 300 mg?

Consideration should be given to using a range of ‘fixed doses’ for a particular drug that could be used as the starting dose and for dose adjustments. Remember that drug elimination varies by at least four-fold between individuals. Can a clinically significant different pharmacodynamic effect be expected between 650 and 700 mg of 5FU? This probably holds true even for carboplatin where doses are determined as a function of glomerular filtration rate. There is still a margin of error in these calculations so dose rounding is also tenable in this situation. The alternative of using a fixed dose for chemotherapy has recently been suggested for cisplatin and irinotecan after investigators found no relationship between BSA and clearance for both of these drugs (de Jongh et al, 2001; Mathijssen et al, 2002).

Guidelines

Guidelines for dose calculation are listed in Table 4 and an example in Table 5. These are not comprehensive and should be used in conjunction with clinical experience and good clinical practice. Some of them are subjective and based on opinion and derived from clinical practice while others are based on best evidence as reviewed in Gurney (1996). The guidelines allow a framework in which to work, in an area currently fraught with uncertainty. As other methods of dose calculation become available, they can be tested against these guidelines and adopted into clinical practice if found to be superior.

As yet there are no useful in vivo measures of drug elimination that can be used for dose calculation. Efforts have been aimed at predicting alteration in drug elimination in those with grossly abnormal liver or renal function with limited success. Carboplatin can be fairly accurately dosed by measuring the GFR. Guidelines exist for dose adjustment of other cytotoxic drugs that are predominantly renally excreted (Kintzel and Dorr, 1995). However, most cytotoxic drugs are largely hepatically eliminated. Attempts at using elevation of serum transaminases and alkaline phosphatase as a guide to dose adjustment have largely failed except perhaps for docetaxel (Alexandre et al, 2000).

Potential drug interactions is an extensive problem and warrants a separate review. Drug elimination can be enhanced by activation of the steroid xenobiotic receptor (SXR) and other nuclear receptors (Synold et al, 2001; Kast et al, 2002). SXR has multiple ligands including rifampicin, dexamethasone, cyproterone acetate, spirinolactone, St John's wort and others. SXR activation leads to upregulation of transcription of many elimination pathways including CYP3A4/5, 2B6, 2C8, MDR1, MRP2 and glutathione-s-transferase. Inhibition of CYP enzymes and MDR1 and probably other efflux pumps can occur with drugs such as cyclosporin, HMGCoA reductase inhibitors, verapamil, omeprazole and cimetidine. However, few clinically significant interactions have been documented or examined for cytotoxic chemotherapy. Anti-convulsant induction of CYP3A4 (phenytoin, phenobarbitone, carbemazepine) has been shown to affect the pharmacodynamics of paclitaxel, irinotecan and tenipisode and concomitant administration of anti-convulsants with chemotherapy has been associated with a worse disease-free survival in children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (Chang et al, 1998; Friedman et al, 1999; Relling et al, 2000). Table 6 lists commonly used drugs which may interfere with cytotoxic drug elimination, focusing on the CYP3A4/MDR1 axis since this is the major elimination route for most cytotoxic drugs and the site of most potential drug interactions.

The future

Studies are underway to define the drug handling genotype and phenotype before drug administration so an individualised dose can be given on the first cycle (Gurney et al, 1998, 2001; Kuehl et al, 2001; Tanabe et al, 2001; Schott et al, 2001; Zhang et al, 2001). Assessment of both hepatic metabolism and active biliary excretion is essential since these are the important elimination processes for the majority of cytotoxic drugs. Such in vivo tests of drug handling would have the advantage of being applicable to a range of cytotoxic and non-cytotoxic drugs, cleared by similar mechanisms.

One scenario is that the majority of patients who have ‘normal’ drug elimination receive a standard fixed dose of drug according to the regimen. Pretreatment in vivo tests of genotype or phenotype will identify the estimated 20 to 30% of patients who fall into the extremes of drug elimination capability. These patients will receive significantly lower or higher fixed doses. In other words, starting doses will be a range of fixed doses according to low, normal or high drug elimination. Fine-tuning of doses will be based on the presence or absence of toxicity or some other parameter that measures biological effect.

BSA-dosing can no longer be viewed as an inaccuracy causing minor inconvenience in treatment of cancer patients. We have the means to solve this problem and it is important that we do so swiftly. Identification of drug handling capability before treatment can allow the abandonment of BSA-dosing and avoid serious but often unrecognised underdosing.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Alexandre J, Bleuzen P, Bonneterre J, Sutherland W, Misset JL, Guastalla J, Viens P, Faivre S, Chahine A, Spielman M, Bensmaine A, Marty M, Mahjoubi M, Cvitkovic E (2000) Factors predicting for efficacy and safety of docetaxel in a compassionate-use cohort of 825 heavily pretreated advanced breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 18: 562–573

Berch J, Wiklund T, Erikstein B, Lidbrink E, Lindman H, Malmstrom P, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen P, Bengtsson NO, Soderlund G, Anker G, Wist E, Ottosson S, Salminen E, Ljungman P, Holte H, Nilsson J, Blomqvist C, Wilking N (2000) Tailored fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide compared with marrow-supported high-dose chemotherapy as adjuvant treatment for high-risk breast cancer: a randomised trial. Scandinavian Breast Group 9401 study. Lancet 356: 1384–1391

Bishop JF, Dewar J, Toner GC, Smith J, Tattersall MH, Olver IN, Ackland S, Kennedy I, Goldstein D, Gurney H, Walpole E, Levi J, Stephenson J, Canetta R (1999) Initial paclitaxel improves outcome compared with CMFP combination chemotherapy as front line therapy in untreated metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 17: 2355–2364

Budman DR, Berry DA, Cirrincione CT, Henderson IC, Wood WC, Weiss RB, Ferree CR, Muss HB, Green MR, Norton L, Frei III E (1998) Dose and dose intensity as determinants of outcome in the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer. The Cancer and Leukemia Group B. J Natl Cancer Inst 90: 1205–1211

Carpenter JT, Maddox WA, Laws HL, Wirtschafter DD, Soong SJ (1982) Favorable factors in the adjuvant therapy of breast cancer. Cancer 50: 18–23

Chang SM, Kuhn JG, Rizzo J, Robins HI, Schold Jr SC, Spence AM, Berger MS, Mehta MP, Bozik ME, Pollack I, Gilbert M, Fulton D, Rankin C, Malec M, Prados MD (1998) Phase I study of paclitaxel in patients with recurrent malignant glioma: a North American Brain Tumor Consortium report. J Clin Oncol 16: 2188–2194

Cortes EP, Holland JF, Wang JJ, Sinks LF, Blom J, Senn H, Bank A, Glidewell O (1974) Amputation and adriamycin in primary osteosarcoma. N Engl I Med 291: 998–1000

de Jongh FE, Verweij L, Loos WJ, de Wit R, de Jonge MJ, Planting AS, Nooter K, Stoter G, Sparreboom A (2001) Body-Surface area-based dosing does not increase accuracy of predicting cisplatin exposure. J Clin Oncol 19: 3733–3739

Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (1998) Polychemotherapy for early breast cancer: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 352: 930–934

Etienne MC, Lagrange JL, Dassonville O, Fleming R, Thyss A (1994) Population study of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 12: 2248–2253

Friedman HS, Petros WP, Friedman AH, Schaaf LJ, Kerby T, Lawyer J, Parry M, Houghton PJ, Lovell S, Rasheed K, Cloughsey T, Stewart ES, Colvin OM, Provenzale JM, McLendon RE, Bigner DD, Cokgor I, Haglund M, Rich J, Ashley D, Malczyn J, Elfring GL, Miller LL (1999) Irinotecan therapy in adults with recurrent or progressive malignant glioma. J Clin Oncol 17: 1516–1525

Gaemlin E, Boisdron-Celle M, Guerin-Meyer V, Delva R, Lortholary A, Genevieve F, Larra F, Ifrah N, Robert J (1999) Correlation between uracil and dihydrouracil plasma ratio, fluorouracil (5-FU) pharmacokinetic parameters, and tolerance in patients with advanced colorectal cancer: A potential interest for predicting 5-FU toxicity and determining optimal 5-FU dosage. J Clin Oncol 17: 1105–1110

George J, Byth K, Farrell GC (1996) Influence of clinicopathological variables on CYP protein. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 11: 33–39

Gurney H, Dodwell D, Thatcher N, Tattersall MHN (1993) Escalating drug delivery in cancer chemotherapy: A review of concepts and practice – part 1. Annals Oncol 4: 23–34

Gurney H (1996) Dose calculation of anticancer drugs: a review of the current practice and introduction of an alternative. J Clin Oncol 14: 2590–2611

Gurney HP, Ackland S, Gebski V, Farrell G (1998) Factors affecting epirubicin pharmacokinetics and toxicity: evidence against using body-surface area for dose calculation. J Clin Oncol 16: 2299–3004

Gurney H, Ackland S, Liddle C, Dunleavey R, Rivory L, Farlow D, Evans S, Garg M, Gebski V, Collins M, Farrell G (2001) Determining the drug elimination phenotype: Hepatic sestamibi scan and midazolam clearance as in vivo tests for drug metabolism and biliary elimination. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 20: 305 (abstract)

Horwich A, Sleijfer DT, Fossa SD, Kaye SB, Oliver RT, Cullen MH, Mead GM, de Wit R, de Mulder PH, Dearnaley DP, Cook PA, Sylvester RJ, Stenning SP (1997) Randomized trial of bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin compared with bleomycin, etoposide, and carboplatin in good-prognosis metastatic nonseminomatous germ cell cancer: a Multiinstitutional Medical Research Council/European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Trial. J Clin Oncol 15: 1844–1852

Hovgaard D, Nissen NI (1992) A phase I/II study of dose and administration of non-glycosylated bacterially synthesized G-M CSF in chemotherapy-induced neutropenia in patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Leuk Lymphoma 7: 3 217–224

International Germ Cell Consensus Classification (1997) A prognostic factor-based staging system for metastatic germ cell cancers. J Clin Oncol 15: 594–603

Kast HR, Goodwin B, Tarr PT, Jones SA, Anisfeld AM, Stoltz CM, Tontonoz P, Kliewer S, Willson TM, Edwards PA (2002) Regulation of multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (MRP2;ABCC2) by the nuclear receptors PXR, FXR, and CAR. J Biol Chem 277: 2908–2915

Kintzel PE, Dorr RT (1995) Anticancer drug renal toxicity and elimination: dosing guidelines for altered renal function. Cancer Treat Rev 21: 33–64

Kuehl P, Zhang J, Lin Y, Lamba J, Assem M, Schuetz J, Watkins PB, Daly A, Wrighton SA, Hall SD, Maurel P, Relling M, Brimer C, Yasuda K, Venkataramanan R, Strom S, Thummel K, Boguski MS, Schuetz E (2001) Sequence diversity in CYP3A promoters and characterization of the genetic basis of polymorphic CYP3A5 expression. Nat Genet 4: 383–391

Mathijssen RHJ, Verweij J, Maja JA, de Jonge MJA, Nooter K, Stoter G, Sparreboom A (2002) Impact of body-size measures on irinotecan clearance: Alternative dosing recommendations. J Clin Oncol 20: 81–87

McIntyre OR, Leone L, Pajak TF (1978) The use of intravenous melphalan (L-PAM) in the treatment of multiple myeloma. Blood 52: Suppl 1 274

Poikenen P, Saarto T, Lundin J, Joensuu H, Blomqvist C (1999) Luecocyte nadir as a marker for chemotherapy efficacy in node-positive breast cancer treated with adjuvant CMF. Br J Cancer 80: 11 1763–1766

Rankin EM, Mill L, Kaye SB, Atkinson R, Cassidy L, Cordiner J, Cruickshank D, Davis J, Duncan ID, Fullerton W, Habeshaw T, Kennedy J, Kennedy R, Kitchener H, MacLean A, Paul J, Reed N, Sarker T, Soukop M, Swapp GH, Symonds RP (1992) A randomised study comparing standard dose carboplatin with chlorambucil and carboplatin in advanced ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer 65: 275–281

Ratain MJ, Mick R, Schilsky RL, Vogelzang NJ, Berezin F (1991) Pharmacologically based dosing of etoposide: a means of safely increasing dose intensity. J Clin Oncol 9: 1480–1486

Ratain MJ (1998) Body-surface area as a basis for dosing of anticancer agents: science, myth, or habit?. J Clin Oncol 16: 2297–2298

Relling MV, Pui CH, Sandlund JT, Rivera GK, Hancock ML, Boyett JM, Schuetz EG, Evans WE (2000) Adverse effect of anticonvulsants on efficacy of chemotherapy for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet 356: 285–290

Samson MK, Rivkin SE, Jones SE, Costanzi JJ, LoBuglio AF, Stephens RL, Gehan EA, Cummings GD (1984) Dose-response and dose-survival advantage for high versus low-dose cisplatin combined with vinblastine and bleomycin in disseminated testicular cancer. A Southwest Oncology Group study. Cancer 53: 5 1029–1035

Schott AF, Taylor LB, Baker L (2001) Individualized chemotherapy dosing based on metabolic phenotype. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 20: 306 (abstract)

Silber JH, Fridman M, DiPaola RS, Erder MH, Pauly MV, Fox KR (1998) First-cycle blood counts and subsequent neutropenia, dose reduction, or delay in early-stage breast cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol 16: 7 2392–2400

Stadtmauer EA, O'Neill A, Goldstein LJ, Crilley PA, Mangan KF, Ingle JN, Brodsky I, Martino S, Lazarus HM, Erban JK, Sickles C, Glick JH (2000) Conventional-dose chemotherapy compared with high-dose chemotherapy plus autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for metastatic breast cancer. Philadelphia Bone Marrow Transplant Group. N Engl J Med 342: 1069–1076

Synold TW, Dussault I, Forman BM (2001) The orphan nuclear receptor SXR coordinately regulates drug metabolism and efflux. Nat Med 7: 584–590

Tanabe M, Ieiri I, Nagata N, Inoue K, Ito S, Kanamori Y, Takahashi M, Kurata Y, Kigawa J, Higuchi S, Terakawa N, Otsubo K (2001) Expression of P-glycoprotein in human placenta: relation to genetic polymorphism of the multidrug resistance (MDR)-1 gene. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 297: 1137–1143

Wrighton SA, VandenBranden M, Ring BJ (1996) The human drug metabolizing cytochromes P450. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm 24: 461–473

Zhang J, Kuehl P, Green ED, Touchman JW, Watkins PB, Daly A, Hall SD, Maurel P, Relling M, Brimer C, Yasuda K, Wrighton SA, Hancock M, Kim RB, Strom S, Thummel K, Russell CG, Hudson Jr JR, Schuetz EG, Boguski MS (2001) The human pregnane X receptor: genomic structure and identification and functional characterization of natural allelic variants. Pharmacogenetics 7: 555–572

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Gurney, H. How to calculate the dose of chemotherapy. Br J Cancer 86, 1297–1302 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6600139

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6600139

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

2D MOF-enhanced SPR detector based on tunable supramolecular probes for direct and sensitive detection of DOX in serum

Microchimica Acta (2024)

-

Chemotherapy-induced neutropenia as a prognostic factor in patients with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer

European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology (2023)

-

Population pharmacokinetics of cisplatin in small cell lung cancer patients guided with informative priors

Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology (2022)

-

Chemotherapy Dose Shapes the Expression of Immune-Interacting Markers on Cancer Cells

Cellular and Molecular Bioengineering (2022)

-

Chemotherapy-induced neutropenia and treatment efficacy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a pooled analysis of 6 randomized trials

BMC Cancer (2021)