Abstract

Study design

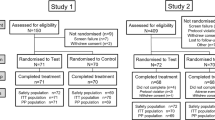

Randomised, controlled, single-blind, three-arm parallel-group trial set in general dental practice with a single general dental practitioner operator/assessor.

Intervention

Seventy-five adult patients, with basic periodontal examination scores of 0 in all sextants, good oral hygiene, at least one sensitive tooth (not diagnosed as pulpitis) and willing to comply with the trial regime were entered into the trial and randomised. Seventy-two participants completed the study. The three interventions were; non-desensitising toothpaste (Colgate Cavity Protection Regular, Colgate-Palmolive, USA), desensitising toothpaste (Colgate Sensitive Fresh Stripe, Colgate-Palmolive, USA) and dentine bonding agent (Seal and Protect, Denpsly, USA). The non-desensitising toothpaste and desensitising toothpastes were provided to the subjects for use at home but dentine bonding agent was applied in the surgery.

Outcome measure

Dentinal hypersensitivity was measured using a participant completed Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) at baseline, two weeks, three months and six months. At baseline and six months a standardised air blast to the buccal cervical root stimulus was used with the VAS. At two weeks and at three months participants self-completed the VAS at home with no stimulus.

Results

Although there was a reduction in dentinal hypersensitivity over time for all three groups, dentinal hypersensitivity reduced significantly (p<0.0001) in both desensitising toothpaste and dentine bonding agent groups. The mean VAS scores in the dentine bonding agent group were statistically significantly lower when compared to both non-desensitising toothpaste (p<0.001) and desensitising toothpaste (p<0.001). In addition, mean scores for non-desensitising toothpaste were higher than desensitising toothpaste (p<0.05).

Conclusions

Dentine bonding agents provided the greatest improvement in dentinal hypersensitivity at two weeks and six months. This reduction was greater than that achieved with the desensitising and non-desensitising toothpastes tested.

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary

Dentinal hypersensitivity is a common problem and patients often present to the dental practice complaining of it as an unpleasant, sudden, sharp pain. Although diagnosed as if it were a disorder itself by exclusion of other pathology, dentinal hypersensitivity is a single symptomatic response to a variety of dental disorders/diseases, which have in common exposed dentine (usually from enamel loss or gingival recession). Despite being of short duration it can have an adverse effect because it is provoked by a variety of stimuli (cold, hot, chemical, evaporative or osmotic) associated with the normal and frequent daily activities of eating and drinking. Research supports our clinical experience that patients find dentinal hypersensitivity to have a negative effect on oral health-related quality of life.1

There is no established pathway for treating dentinal hypersensitivity, and a wide variety of treatment strategies including lasers and fluoride iontophoresis have been recommended. However, the most widely used strategies are desensitising toothpastes and professionally applied desensitising agents, both of which have a wide variety of formulations and active ingredients. Although a number of studies have compared different treatments, there is no comprehensive systematic review of all treatments or even of all desensitising toothpastes. The Cochrane review of desensitising toothpastes only included potassium nitrate pastes and was last updated in 2006.2 A more recent systematic review of professionally applied desensitising agents3 found them to be effective but didn't compare them to desensitising toothpastes. This leaves the clinician unable to judge whether any/all of these strategies for managing dentinal hypersensitivity are effective and which are relatively more effective and worth using.

This practice-based study, carried out by a single practitioner, using random allocation of patients to three groups, compared a desensitising toothpaste with a professionally applied desensitising agent and a non-desensitising toothpaste. Although this was a small study with 72 participants completing it (75 were enrolled), it was tightly controlled and well carried out. The manuscript lacks some detail, as it doesn't give much information on what the participants actually did with the toothpaste they were given; they were told to follow their usual oral hygiene regimes but we don't know what these were. Also, it is implied that the participants did maintain fidelity to the arm they were randomised to, and complied by staying with the toothpaste they were given, but this isn't stated explicitly and there seems to have been no verification carried out. There is also a lack of information on how many times the desensitising agent was professionally applied, although it seems to have been only a single time and then followed up over six months. Assuming that the Visual Analogue Scale scoring ran from 0 to 100, as is implied, there does seem to have been a clinically as well as a statistically significant benefit over six months for the desensitising agent, followed in effectiveness by the desensitising toothpaste.

The study only includes those individuals with basic periodontal scores of 0 in all sextants and suffering from dentinal hypersensitivity of one tooth. The evidence-based practitioner would therefore wonder how these results are generaliseable to their patient base in general. One could speculate that the treatment effects of such interventions could be even greater in a patient cohort with advanced recession or generalised dentinal hypersensitivity. Future studies may wish to consider including those with generalised dentinal hypersensitivity, which may better represent the population.

Although the authors say that a placebo control group may have added to the interpretation of the pain value measurements that the study gave, in deciding whether the study results are likely to be replicated in a general practice patient population, a placebo group is arguably not necessary. It is unlikely that any group of patients would present having not tried even non-desensiting toothpaste, and the widespread advertising of different toothpastes with various ‘innovative technologies’ (whether backed by high quality evidence or not) means that many patients will have accessed these as first line treatments. So, the groups investigated by the researchers in this study are meaningful to the clinician.

A recent observational study4 of 3,187 young European adults found that around half of them experienced dentinal hypersensitivity, and there was a significant association with erosive tooth wear and gingival recession. As with so many things in dentistry, the importance of the practitioners' role in early detection both of erosion and gingival recession is worth emphasising. Early detection would allow instigation of preventive measures for erosive tooth wear and periodontitis, reducing unpleasant dentinal hypersensitivity and reparative treatment.

By comparing desensitising agents (more expensive and less convenient for patients) and desensitising toothpastes (readily available and can form a normal part of oral hygiene) with non-desensitising toothpastes, this study supports the practitioner in applying a desensitising agent and additionally recommending patients use desensitising toothpastes to give some relief from dentinal hypersensitivity. Given the number of studies that have been carried out, a comprehensive systematic review with sound interpretation into a clinical guideline/pathway would be useful for clinicians and patients.

References

Bekes K, Hirsch C . What is known about the influence of dentine hypersensitivity on oral health-related quality of life? Clin Oral Investig 2013; 17 Suppl 1: S45–51. doi: 10.1007/s00784-012-0888-9 . Epub 2012 Dec 6.

Poulson S, Errboe M, Lescay Mevil Y, Glenny AM . Potassium containing toothpastes for dentine hypersensitivity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; 3: CD001476.

da Rosa WL, Lund RG, Piva E, da Silva AF . The effectiveness of current dentin desensitizing agents used to treat dental hypersensitivity: a systematic review. Quintessence Int 2013; 44: 535–546.

West NX, Sanz M, Lussi A, Bartlett D, Bouchard P, Bourgeois D . Prevalence of dentine hypersensitivity and study of associated factors: a European population-based cross-sectional study. J Dent 2013; 41: 841–851.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Address for correspondence: P.A. Brunton, Restorative Dentistry, Leeds Dental Institute, Clarendon Way, Leeds LS2 9LU, UK. E-mail: p.a.brunton@leeds.ac.uk

Gibson M, Sharif MO, Smith A, Saini P, Brunton PA. A practice-based randomised controlled trial of the efficacy of three interventions to reduce dentinal hypersensitivity. J Dent 2013; 41: 668–674.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lamont, T., Innes, N. Study suggests dentine bonding agents provided better relief from dentine hypersensitivity than a desensitising toothpaste. Evid Based Dent 14, 105–106 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400965

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400965