Abstract

Design

Placebo controlled randomised controlled trial (RCT).

Intervention

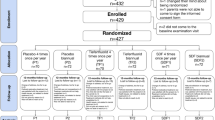

Recruited children were randomly assigned to either a treatment (5% NaF varnish, n = 198) or a control group (placebo, n = 181). Data on oral health habits and socio-demographic characteristics was collected from the children by trained interviewers. Diet information was collected using a seven day food frequency diary. Caries was assessed using the International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS).

Outcome measure

The main outcome was decayed and filled surfaces (DFS) increment at 12 months.

Results

Two hundred and ten (55.4%) children having one or two applications of fluoride varnish or placebo were available for follow-up at 12 months. At the baseline examination, the children in the treatment and control groups presented with on average 6.2 and 5.6 DFS, respectively (P < 0.001). At 12 months, the children in the varnish group showed significantly lower DFS increments than did children in the control group (10.8 versus 13.3; P < 0.007), with a preventive fraction (PF) of 40% (95% CI: 34.3–45.7%; P < 0.0001)

Conclusions

The results of this study suggest that applications of 5% NaF varnish can be recommended as a public health measure for reducing caries incidence in this high-caries-risk population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary

The 2009 Cochrane review on topically applied fluoride varnish demonstrated substantial effectiveness in preventing dental caries in both the permanent and deciduous dentition.1 This evidence is a key component of the UK Department of Health evidence-based toolkit for prevention2 and the Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (SDCEP) guidance on the prevention and management of dental caries in children.3 In Scotland, the national child oral health improvement programme, Childsmile, has been developed to implement this guidance through changes to the primary care dental contract and nursery and school fluoride varnish initiatives.4

Since the 2009 review a further two randomised controlled trials have been published. The first, a recent trial among school children in North West England5 found that there was limited evidence of effectiveness of fluoride varnish within a public health programme. This study was undertaken in seven-eight year-olds, with a small amount of varnish applied only to permanent molars, and with no particular focus on young children or those from deprived or high-caries risk groups. The second of these studies is the paper reviewed here.

This study by Arruda and colleagues aims to demonstrate the efficacy of 5% fluoride varnish in preventing decayed and filled surfaces increments among children with a high caries risk. In this RCT patients between the ages of seven and 14 were recruited from three schools in rural Brazil. Over a period of 24 months, each school was visited four times at six-monthly intervals for recruitment, examination and varnish application. Some concerns about the study design mean the findings need to be interpreted with an element of caution, including: the relatively small numbers (n=210) included in the final analysis (justified in the paper with an insufficiently described power calculation); the lack of clarity in the Consort flowchart; and the method of randomisation – which was not the most robust, with children being allocated into either the intervention or control group on the basis of odd and even ID numbers by coin flipping, opening the study to potential bias. The study's strengths include the use of a true identical placebo for the control, and of the International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS) for detecting early enamel caries lesions – although this was not as well detailed as would be needed for others to repeat.

Nevertheless, the main findings were of significantly lower caries increments in the fluoride varnish intervention group compared to the placebo control, with a preventive fraction of 40% - which is the percentage of tooth surfaces where caries were prevented by fluoride varnish.

Despite these results, it is widely recognised that there is a need for further evidence in this area as stated in the Cochrane review. In the UK there are three other clinical trials underway – one in Northern Ireland in a dental practice setting,6 another in Wales assessing fluoride varnish versus pit and fissure sealants,7 and a trial embedded within the Childsmile programme focusing on effectiveness of fluoride varnish in three- and four-year-olds.4 It will be interesting to see how the evidence develops over coming years – specifically in relation to fluoride varnish use as a public health community measure and across different age-groups.

References

Marinho VC, Higgins JP, Logan S, Sheiham A . Fluoride varnishes for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002; Issue 1. Art. No. CD002279.

Delivering Better Oral Health: An evidence-based toolkit for prevention. Department of Health / British Association for the Study of Community Dentistry, 2009.

SDCEP Prevention and Management of Dental Caries in Children. Dundee: Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme, 2010.

Childsmile [website]

Milsom KM, Blinkhorn AS, Walsh T . A cluster-randomized controlled trial: fluoride varnish in school children. J Dent Res 2011; 90: 1306–1311.

Tickle M, Milsom KM, Donaldson M . Protocol for Northern Ireland Caries Prevention in Practice Trial (NIC-PIP) trial: a randomised controlled trial to measure the effects and costs of a dental caries prevention regime for young children attending primary care dental services. BMC Oral Health. 2011; 11: 27

Cardiff University. Seal or Varnish. A randomised trial to determine the relative cost and effectiveness of pit and fissure sealants and fluoride varnish in preventing dental decay. Protocol NIHR Health Technology Assessment programme http://www.hta.ac.uk/protocols/200801040004.pdf

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Address for correspondence: Woosung Sohn, Department of Health Policy and Health Services Research, Boston University Henry M. Goldman School of Dental Medicine, 560 Harrison Ave, 3rd floor, Boston, MA 02118, USA. E-mail: woosung@bu.edu

Arruda AO, Senthamarai Kannan R, Inglehart MR, Rezende CT, Sohn W. Effect of 5% fluoride varnish application on caries among school children in rural Brazil: a randomized controlled trial. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2012; 40: 267–276.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Greig, V., Conway, D. Fluoride varnish was effective at reducing caries on high caries risk school children in rural Brazil. Evid Based Dent 13, 78–79 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400874

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400874

This article is cited by

-

Enamel Resistance to Demineralization After Bracket Debonding Using Fluoride Varnish

Scientific Reports (2017)