Abstract

Design

Randomised controlled trial

Intervention

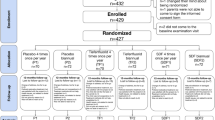

Elders having at least five teeth with exposed roots, no serious medical problems and basic self-care ability (including oral hygiene practices) were randomly allocated into one of four prevention groups. Individualised oral hygiene instruction was provided to each participant, focusing on effective brushing with a manual toothbrush, and use of fluoride toothpaste was recommended. Before applications of the study agents, a piece of gauze was used to clean and dry the teeth. Then water (placebo control), chlorhexidine varnish (Cervitec, Ivoclar Vivadent AG, Schaan, Liechtenstein), sodium fluoride varnish (Duraphat, Pharbil Waltrop GmbH, Waltrop, Germany) or SDF solution (Saforide, Toyo Seiyaku Kasei Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan) was applied onto the exposed root surfaces of participants in the respective groups by means of a disposable microbrush. The participants were instructed not to eat for half an hour after treatment. Applications of water or SDF solution were repeated every 12 months, and applications of chlorhexidine varnish or sodium fluoride varnish were repeated every three months.

Outcome measures

Root Caries Index (RCI) was calculated as follows: (no. of root caries lesions/no. of teeth with gingival recession/person) × 100. Treatment effects were also measured by prevented fraction (PF), relative risk and the number (of elders) needed to treat (NNT) to prevent one elder from developing root caries.

Results

Results Two thirds (203/306) of the included elders were followed for three years. Significantly lower relative risks for developing new root caries were found in the elders in the chlorhexidine, sodium fluoride and SDF groups compared with the control (OHI only) group. The mean numbers of new root caries surfaces in the four groups were 2.5, 1.1, 0.9 and 0.7 respectively (ANOVA, p < 0.001). The prevented fraction and numbers needed to treat are shown in Table 1.

Conclusions

Applications of SDF solution, sodium fluoride varnish and chlorhexidine varnish are more effective in preventing new root caries than OHI alone. The results of this study provide support for the clinical and community use of the three test materials, in addition to improvement in oral hygiene, to prevent the development of root caries in institutionalised elders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary

Root surface caries is often thought of as a modern disease, however examinations of the dental remains in prehistoric, Bronze Age (1800-700BC) populations have shown that root caries accounted for 68% of all carious teeth recorded1 even in these ancient times.

With this in mind it might be prudent to consider some current background knowledge of root surface caries disease before assessing the intricacies of this randomised controlled clinical trial (RCT). A recent systematic review estimated that root caries incidence was 23.3% (95% confidence interval, 17.1-30.2%) and suggested that older adults may experience similar or higher levels of new caries than do school children, who are the primary recipients of caries-prevention programmes.2 It is possible that the magnitude of the root caries problem will grow in the coming years as the aging population swells and the retention of teeth increases.3

When diagnosing root surface caries it is important to distinguish between active and inactive lesions. Fejerskov and colleagues described nine different diagnostic categories ranging from inactive to active lesions and including expectation of pulpal involvement and whether a root surface filling was already present. They also reported that the buccal surfaces of lower molars and premolars and upper canines were the most severely affected with root surface caries.4 Modern diagnosis of root surface caries is based on tactile and visual criteria (colour and appearance)5 and may be supported in the future with other methods such as electrical caries measurements6 or laser fluorescence.7

Already over 20 years ago it was shown that the activity of root caries lesions can be reduced using meticulous tooth brushing with a fluoride toothpaste.8Two other commentaries from this journal have dealt with root surface caries treatment. Richards summarised that fluoride has a beneficial effect on root caries.9 A further summary described the limited evidence of the effect of chlorhexidine varnish (CHX-V) on root caries.10 Recently a randomised controlled trial, also involving older adults (58–84 years of age) has reported that primary root caries lesions may be reversed after daily intake of milk supplemented with fluoride and probiotic lactobacilli.11

In this RCT patients were recruited from an outreach dental program where dental care was provided to several thousand patients.12 This study population of 306 participants was derived from elders living in 21 residential and nursing homes for the aged in Hong Kong. The same research group described another randomised controlled trial comparing two restorative interventions to treat root surface caries in 103 elders from the same overall population.13 The relationship of the two separate study groups to each other and to the overall population was not reported. Indeed it is not clear if any of the tooth root surfaces were filled prior to inclusion.

The selection of elders with at least five teeth with exposed roots was reported but the extent to which the roots were exposed, how this recession might have changed over the study period and the pulpal vitality, endodontic status and periodontal parameters were lacking.

One third of the participants dropped out of the study, which is a significant number, even when the investigators report that dropout rates were similar in the four groups. It is not clear if the reasons for dropout were also equally distributed in the four groups.

The baseline measurements were recorded at the same time as the interventions were administered, although by different dentists. A run out of the baseline data for a year for example may have provided valuable initial data before the study started. Another possibility may have been a cross-over design but this would add complexity and may result in even more dropouts.

It was also not clear to what extent the 21 different centres were dissimilar. Although it was conveyed that the participants did not have free access to sugar, this is not the same as measuring or recording sugar intake with for example diet analysis data.

Root caries was recorded as present when a suspect root lesion 'could be easily penetrated by a sharp sickle-shaped probe with light force'. No other diagnostic types of root surface lesion were recorded and this may be a shortcoming. The definition of light force was also not reported. It would have been interesting, from a clinical perspective, to know in which teeth and surfaces the resulting new root surface caries were recorded.

Quality assessment of reports of randomised controlled trials often assess whether the randomisation methods, allocation concealment and blinding were adequate or not.14

In this trial random assignment was undertaken by drawing numbers from a bag. Ideally assignment should be concealed and occur at the latest time-point possible. As all groups received oral hygiene instruction (OHI) it would have been possible to assign to the appropriate group after OHI. Experienced clinicians may have been able to un-blind the interventions – water (placebo) being easier to differentiate from the three other test materials. From the report it is not possible to ascertain if allocation concealment and blinding were adequate. Systematic reviewers, who include this RCT in the future, may decide to investigate these issues further.

The number of elders needed to treat (NNT) for chlorhexidine, sodium fluoride and silver diamine fluoride (SDF) were 3.2, 3.1 and 2.5 respectively. The best NNT is 1, when everyone experiences benefit with the treatment and no one with the control, although there are no set limits for NNTs to be considered clinically effective. In this case, with overlapping confidence intervals, there appear to be similar results in all groups and a final decision on which therapy to use in clinical practice may come down to personal choice of either patient, clinician or both or other factors such as cost and practicality.

Those undertaking randomised controlled trials need to take account of systematic reviews in their specialist areas. Systematic reviews may play several roles – assimilating the evidence from more than one study, be that narratively or quantitatively, identifying gaps in the evidence for future research and exactly defining, for example, the inclusion criteria used and proposed for future studies. A systematic review may also address the economic factors of different interventions to inform patients, clinicians and other stakeholders of this important aspect. Systematic reviews should be seen as works-in-progress, periodically updated as evidence changes. With this in mind 'clinical trials should begin and end with systematic reviews of relevant evidence'.15 For this reason, although this trial describes the addition of three test materials, in addition to improvement in oral hygiene as being effective to prevent the development of root caries in institutionalised elders in this specific population – it may be wise to wait for a systematic review of this topic to assess the reproducibility and generalisability of this result especially with reference to other population groups and settings.

References

Molnar S, Molnar I . Observations of dental diseases among prehistoric populations of Hungary. Am J Phys Anthropol 1985; 67: 51–63.

Griffin SO, Griffin PM, Swann JL, Zlobin N . Estimating rates of new root caries in older adults. J Dent Res 2004; 83: 634–638.

Fejerskov O, Kidd E, and Kidd EAM . Dental caries: the disease and its clinical management. Wiley-Blackwell; 2008

Fejerskov O, Luan WM, Nyvad B, Budtz-Jørgensen E, Holm-Pedersen P . Active and inactive root surface caries lesions in a selected group of 60- to 80-year-old Danes. Caries Res 1991; 25: 385–391.

Topping GV, Pitts NB, International Caries Detection and Assessment System Committee. Clinical visual caries detection. Monogr Oral Sci 2009; 21: 15–41.

Neuhaus KW, Longbottom C, Ellwood R, Lussi A . Novel lesion detection aids. Monogr Oral Sci 2009; 21: 52–62.

Rodrigues JA, Lussi A, Seemann R, Neuhaus KW . Prevention of crown and root caries in adults. Periodontol 2000 2011; 55: 231–249. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0757.2010.00381.x.

Nyvad B, Fejerskov O . Active root surface caries converted into inactive caries as a response to oral hygiene. Scand J Dent Res 1986; 94: 281–284.

Richards D . Fluoride has a beneficial effect on root caries. Evid Based Dent 2009; 10: 12.

Duane B . Limited evidence of the effect of chlorhexidine varnish (CHX-V) on root caries. Evid Based Dent 2011; 12: 39–40.

Petersson LG, Magnusson K, Hakestam U, Baigi A, Twetman S . Reversal of primary root caries lesions after daily intake of milk supplemented with fluoride and probiotic lactobacilli in older adults. Acta Odontol Scand 2011; May 12 [Epub ahead of Print]

Lo EC, Luo Y, Dyson JE . Outreach dental service for persons with special needs in Hong Kong. Spec Care Dentist 2004; 24: 80–85.

Lo EC, Luo Y, Tan HP, Dyson JE, Corbet EF . ART and conventional root restorations in elders after 12 months. J Dent Res 2006; 85: 929–932.

He J, Du L, Liu G, Fu J, He X, Yu J, Shang L . Quality assessment of reporting of randomization, allocation concealment, and blinding in traditional Chinese medicine RCTs: a review of 3159 RCTs identified from 260 systematic reviews. Trials 2011; 12: 122.

Clarke M, Hopewell S, Chalmers I . Clinical trials should begin and end with systematic reviews of relevant evidence: 12 years and waiting. Lancet 2010; 376: 20–21.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Address for correspondence: ECM Lo, Faculty of Dentistry, The University of Hong Kong, 3/F Prince Philip Dental Hospital, 34 Hospital Road, Hong Kong SAR, China. E-mail: edward-lo@hku.hk

Tan HP, Lo EC, Dyson JE, Luo Y, Corbet EF. A randomized trial on root caries prevention in elders. J Dent Res 2010; 89: 1086–1090. Epub 2010 Jul 29

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sequeira-Byron, P., Lussi, A. Prevention of root caries. Evid Based Dent 12, 70–71 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400805

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400805