Abstract

Women with a family history of breast cancer dominate referrals for cancer genetic risk counselling across Europe. Given limited health care resources, managing this demand, while achieving good value for money for health services, is a major challenge. The paper reports the benefits and associated costs of moving from a traditional system of deriving family history of cancer during the patient's initial clinic attendance, to a protocol-driven system with pre-counselling assessment of family history. The evaluation was based on retrospective clinical data and a clinical audit. Changes in risk between referral and final risk assessment were ascertained and the cost difference between the two systems estimated. The study results showed that 14% of women assessed as ‘low’ genetic risk at referral were reassessed as ‘moderate’ or ‘high’ genetic risk for breast cancer following verification of family history. Sixteen per cent of those assessed as ‘moderate’ or ‘high’ genetic risk at referral were reassessed as ‘low’ genetic risk for breast cancer. Compared to the traditional system, the new protocol-driven system of risk assessment was more consistent, which reduced the number of return appointments and created time for clinicians to spend with other patients. The estimated cost of family history verification and genetic clinic appointment was calculated as £91.68 (€132.53) per family history, compared to £104.00 (€150.34) for the traditional system, representing a slight reduction in health service costs. Finally, the protocol-driven system can be used as part of ongoing audit for planning future genetics services in Scotland.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer is responsible for 27% of all new cancer cases in women across Europe and 17.5% of all cancer deaths.1 The known inherited susceptibility genes, BRCA1 and BRCA2, give rise to increased lifetime risks of developing the disease, often at an earlier age.2 Cumulative lifetime risks have been variously quoted as 65–87% for BRCA13, 4 and 45–84% for BRCA2.3, 5 Cancer genetic counselling aims to identify individuals with a significantly increased genetic risk of cancer and counsel them on appropriate risk management to reduce disease morbidity and mortality.6 Patient access to surveillance, genetic testing and other care usually depends on the outcome of this counselling and risk assessment.7 It is important that the counselling not only appropriately identifies women at increased genetic risk of breast cancer8 to ensure appropriate referral for surveillance, but also identifies those women at low risk early, so as to reduce unnecessary anxiety.9 Cancer risk counselling should also take into account patients’ understanding of risk and modifying behaviours associated with cancer risk, emotional concerns, discussion of family communication strategies and potential family reactions.

Despite the use of referral guidelines, most genetic clinics face increasing demands for breast cancer genetic counselling. Indeed, women with a family history of breast cancer dominate referrals for cancer genetic risk counselling in the United Kingdom (UK) and throughout most of Europe.8, 10, 11 Given fixed budgets and limited health care resources,12 managing this demand while achieving good value for money for health services is a major challenge.

This paper presents an evaluation of alternative approaches to breast cancer risk assessment in the Aberdeen Genetic Clinic, Scotland. The paper reports the benefits and associated costs of moving from the traditional system of deriving family history of cancer during the patient's initial clinic attendance, to a new protocol-driven system with pre-counselling assessment of family history.

Alternative counselling systems

The Aberdeen Genetic Clinic, based at Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, serves a population of 5 21 000 in the Grampian region of Scotland. Breast cancers diagnosed in Grampian, Orkney and Shetland account for 11.6% of all Scottish breast cancers (ISD Scotland). Since 1991, the traditional system of risk estimation in Aberdeen was to obtain a family history of cancer from the patient during their first clinic appointment, which was later verified by individual geneticists. Patients were often recalled for follow-up appointments if there was insufficient family information to offer advice on cancer risks and surveillance. Follow-up appointments were also given if there was a change in advice following family history verification. This process of some patients requiring more than one appointment and time spent by clinicians verifying family histories was considered an inefficient use of limited health service resources. Therefore, alternative counselling systems were explored.

One alternative model considered was protocol-driven system where family histories were obtained by specialist genetic nurses or genetic associates by phone call, visits or questionnaire. Family histories would be verified partially or fully before clinic appointments with a clinical geneticist. A second alternative was to perform triage on referral letters, only seeing patients and obtaining further family history if there appeared to be a moderate or high genetic risk indicated in the referral letter. The third alternative, a protocol-driven system involved obtaining family histories by questionnaire, with subsequent verification from case records, cancer registries or death certificates, co-ordinated by a database manager, before the clinic appointment. This final system was the one adopted in Aberdeen.

The protocol-driven system, co-ordinated by a dedicated database manager, was considered the most appropriate in Aberdeen because it could be adapted to perform clinical audit as well as providing the required service. This system has been used in other genetic clinics, with the one in Aberdeen based on a model used by the Department of Medical Genetics in Birmingham (UK).

This paper reports the results of a retrospective evaluation of the benefits and associated costs of moving to the new protocol-driven system for pre-counselling assessment of family in Aberdeen.

Methods

To evaluate the costs and benefits of the two alternative counselling systems, an ongoing audit of cancer genetics services for Aberdeen was used as a basis for data collection. The first part of the evaluation examined the change in the assessment of risk process between the traditional and the new protocol-driven system, with the second part assessing whether the introduction of the automated system had made a difference in health service resource use and costs.

A total of 371 patients with a family history of cancer were referred to the Aberdeen Genetic Clinic during the 7-month evaluation period between 1 January and 31 July 2000. Of these, 185 were referrals including a family history of breast cancer (that is breast, breast/ovarian, breast/colon, breast/other including Li-Fraumeni or miscellaneous cancers).

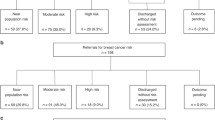

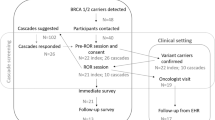

As part of the service for the evaluation period, patients with a family history of cancer were asked to provide family history information before their clinic appointment. These patients were sent a letter and a family history questionnaire for completion. The diagnoses in relatives said to be affected by cancer were then verified as far as possible by the database manager and specialist genetic nurse, using cancer registries, hospital notes and death certificates. Written consent was obtained from living relatives via the referred patient (they were not contacted directly). In a few cases, it was also possible to obtain information outside Scotland, with appropriate consent from affected individuals. This process is summarised in the flow chart in Figure 1.

All patients were then seen at the genetic clinic either by a consultant, associate specialist, staff grade doctor, specialist registrar or specialist genetic nurse. Additional family history information was obtained at the clinic in some cases. The risks for breast cancer were assessed from the referral letters, family history questionnaires sent to the patients before clinic appointment and all the information available following the clinic appointment. Risks were assessed using Scottish Guidelines 2001 adopted previously by Cancer Genetics Services throughout Scotland (Table 1). Changes in the risk estimation throughout the process were ascertained and compared for each risk group, with a non-parametric Wilcoxon test used to test for statistical significance.

Generally those at ‘high’ genetic risk had a lifetime risk of breast cancer of greater than 35–40% up to age 85. Those in the ‘moderate’ risk category had a lifetime risk of 20–35% and those at ‘low’ genetic risk had a lifetime risk of less than 20% (ie still greater than the average population).

Recommended surveillance for those in the ‘high’ and ‘moderate’ risk category is by mammography from 5 years younger than the youngest affected, but starting from an age not younger than 35 and not more than 40 years. Mammograms are offered every 2 years for those aged 35–40 years and then annually from age 40 to 50. Those in the ‘high’ risk category are offered 18 monthly mammograms from age 50 to 64, then three yearly mammograms as part of the NHS Breast Screening Programme (NHSBSP). Those in the ‘moderate’ category are offered three yearly mammograms from age 50 onwards (NHSBSP). Those in the ‘low’ genetic risk category are not offered extra surveillance but are encouraged to take part in the NHSBSP from age 50 onwards. These recommendations are being reviewed following the introduction of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines for familial breast cancer.

A cost analysis was performed to examine whether the introduction of a pre-counselling assessment had any impact upon health service resource use. This was achieved by calculating the difference in cost between the traditional system and the new protocol-driven system. A detailed microcosting was performed, rather than relying on tariffs or charges, which are unlikely to represent the true costs of counselling. This approach also has the added advantage of collecting detailed information on resource use, which should help to increase the generalisability of the results, due to its transparency. The resources examined were staff costs and room costs for the counselling itself (1-h session), computing, administrative support costs and time spent assessing risk. For the automated system, resources were required for a data-input manager, increased nurse counsellor time and additional administration costs. The mid-point of the salary scale for each grade of staff was used to reflect a ‘replacement’ aspect and employer's on-costs (National Insurance and Superannuation) were included at 13%.

For room and equipment costs, it was assumed that both counselling systems used a similar level of resources. Room costs were estimated for direct counselling time. This included the cost of using the building and overheads in an outpatient clinic. The size of the floor space used for counselling was established first and for the building costs, a local unit cost was applied for a new hospital building in Aberdeen. An equivalent annual cost (EAC) calculation was then performed, which automatically incorporates both the depreciation and opportunity cost aspects of the capital items such as buildings and computers, with the opportunity cost of capital reflected in the discount rate.13 The EAC for building costs used a 3.5% discount rate, as specified by UK Treasury14 over a 50-year life span and 5 years for computers. Overheads are those costs shared by the entire hospital such as heating, lighting and cleaning. The amount of time required for a consulting room was combined with floor space to measure overheads, which were then valued using hospital finance data from Grampian. The costs were then averaged according to the number of patients seen in the different time periods. Sensitivity analysis was performed to examine the effect of changing any assumptions used. All costs were updated to 2006 prices and presented in British pounds (£) and Euros (€).

Results

Fourteen per cent (25/185) of patients did not return their family history questionnaire, despite written reminders and telephone messages, 9% (16/185) of whom attended their clinic appointment. Half of the questionnaire non-responders who attended brought their questionnaires with them for the appointment. Thirty-six per cent (9/25) of all questionnaire non-responders were given a ‘moderate’ or ‘high’ final risk (representing 5% (9/185) of all breast cancer referrals to genetic clinic). Table 2 presents information on clinic non-attenders. In total, 10 patients did not attend clinic appointments or respond to repeated invitations to the clinic (nine were questionnaire ‘non-responders’ and one was assessed as ‘high’ risk from the referral letter). The non-attendance rate for patients under the protocol-driven system was comparable with the rate for the previous traditional system.

For those who did attend the genetic clinic, 14% (10/74) of those thought to be ‘low’ risk at referral were given a ‘moderate’ or ‘high’ final risk, and therefore offered mammographic surveillance, representing 5% (10/185) of all breast cancer referrals to the genetic clinic (Table 3). Sixteen per cent (15/96) of those thought to be ‘moderate’ or ‘high’ risk at referral were given a ‘low’ final risk, and therefore were not offered mammographic surveillance (8% (15/185) of all breast cancer referrals to genetic clinic). It was not possible to assess risk from the referral letter in 15 patients, 33% (5/15) of whom were given a ‘moderate’ or ‘high’ final risk (3% (5/185) of all breast cancer referrals to genetic clinic).

This compares with 101 breast cancer patients seen at the Aberdeen Genetic Clinic in the period 1994–1995, the most recent period for which comparable audit data were available including age, cancer syndrome and risk status (Table 4). Twenty patients were assessed to be ‘low’ risk at referral, 64, ‘moderate’ and 17, ‘high’ (reassessed using current Scottish guidelines). Assessment of final risk for this group meant that one ‘low’ risk and three ‘moderate’ risk patients were subsequently thought to be at ‘high’ risk (4% (4/101) of referrals), 21 ‘moderate’ risk and eight ‘high’ risk patients were downgraded to ‘low’ (29% (29/101) of all referrals). While these differences are not statistically significant (Z score, 0.970 and P=0.332), probably due to the small numbers in some groups, they are important differences in terms of patient care.

In both groups, there were patients for whom it was not possible to assess risk at referral. The reason for this was generally insufficient details provided in the referral letter (generally from a family doctor) to estimate the risk level. The quality of information given in referral letters was comparable under both the ‘traditional’ and the ‘new protocol’ systems.

The number of return appointments required for breast cancer family patients were ascertained for the 7-month period from 1 July 2000 to 31 January 2001, when most patients from the evaluation cohort would be expected to be given return appointments if necessary. These were compared with the return appointments for a similar 7-month period in the preceding year (1 July 1999–31 January 2000), for patients who were seen before the introduction of the protocol-driven system. A significantly higher number of patients, 13% (23/172), required a second genetic appointment following verification of family history under the traditional system compared with 7% (13/185) under the automated system (χ2=3.96, P=0.047).

Table 5 presents the results of the cost analysis. The move to the protocol-driven system cost £12.32 (€17.81) less per patient than the traditional system. This small difference in cost was largely due to the salary of the data manager and nurse, which was less expensive in preparing pedigrees and gathering information than individual clinicians. Capital and consumable costs were slightly higher in the protocol-driven system, but the difference was small.

Discussion

The importance of verification of a family history of cancer has been reported previously.8, 15, 16 For several years in Aberdeen, the traditional system of breast cancer risk assessment in genetic counselling was to wait until the first clinic appointment to obtain family history, and then verified by each individual doctor or specialist genetic nurse before assessing a final risk. As this appeared to be an inefficient use of resource, the Aberdeen clinic changed to a system of obtaining and verifying family histories in advance of clinic appointments, in line with many genetics centres throughout the United Kingdom.

This paper has shown that there are several potential advantages of moving to the new protocol-driven system. For example, the new system creates less variation as a centralised team consisting of a data manager and genetic nurse, and increases efficiency and standardisation of preparation work compared to several geneticists undertaking preparation individually. The new protocol-driven system reduces the need to offer return appointments to patients once family history has been investigated. This also has the follow-on effect of helping to reduce waiting list times by reducing administration time and review appointments, allowing clinicians to see other patients and undertake research. Finally, as data from the counselling service is now recorded, it can be fed into local and Scottish Office audit, and used to inform the planning of future genetics services.

Confirmation of family history alters final risk assessment and appears to facilitate more accurate targeting of surveillance for those at increased genetic risk for breast cancer, while avoiding unnecessary screening in those at ‘low’ genetic risk. Undertaking pre-consultation confirmation of family history appears to be effective, acceptable and efficient.

In addition, the estimated mean cost per patient for verifying family history and undergoing a genetic clinic appointment was calculated as £91.68 (€132.53), compared to £104.00 (€150.34) for the traditional system, representing a slight reduction in health service costs with the new system. Statistical testing of difference in cost was not possible because of lack of information on variation between patients. While a difference of £12.32 (€17.81) is small, it is important to note that most new ways of offering care tend to increase rather than decrease health service costs and that this money could be devoted to an alternative use.

In terms of the potential limitations of our study, there are several points to highlight. First, with the protocol-driven system, one-third of the women who did not return their questionnaire before being sent a clinic appointment subsequently failed to attend their appointment. Of the remaining two–thirds who did attend, half brought their completed questionnaires to their appointment. A number of these did not attend their initial appointment, but subsequently requested a further appointment (one had more than five attempts). This may be a group with a high degree of anxiety, but it is not clear how they can be differentiated from other referrals to prevent ‘wasted’ appointments. Due to rising waiting lists, the Aberdeen clinic has reviewed its policy of sending appointments to non-responders, although concerns remain about the reasons for non-response in this group. In addition, the clinic has also reviewed its policy of seeing all referrals regardless of risk, and has adopted the practice of sending a letter rather than an appointment to those patients found to be at low risk after confirmation of family history. Patients are informed in the letter that they may still request a clinic appointment if they wish to be seen.

A further potential limitation of our study is that we do not have information on any psychosocial outcomes associated with the different systems, due to the retrospective nature of data collection of the traditional system. Previous studies have explored psychosocial outcomes in cancer genetic counselling, such as women's perceived risk of breast cancer and patient satisfaction, in nurse versus doctor led counselling and counselling in different genetics centres. However, these studies found few significant differences between alternative service delivery methods.6, 7, 9

Further modifications that have been introduced in the protocol-driven system include review of the patient questionnaire by a specialist genetic nurse, to ascertain which cancer diagnoses require confirmation. This process will result in further savings, where the verification of a diagnosis will not alter the management of the patient.

Conclusion

Compared to the traditional system of starting to verify family history of breast cancer during the first clinic appointment, the new protocol-driven system of risk assessment was found to be more efficient and consistent, producing a small reduction in the number of return appointments and freeing up time for clinicians to spend with other patients. This was achieved at a lower cost than the standard system and has the added advantage of collecting data that can be used as part of ongoing audit for planning future genetics services in Scotland.

References

Tyczynski JE, Bray F, Maxwell Parkin D : Breast Cancer in Europe. ENCR Cancer Fact Sheets, vol. 2, 2002.

Claus EB, Risch N, Thompson WD : Autosomal dominant inheritance of early-onset breast cancer. Implications for risk prediction. Cancer 1994; 73: 643–651.

Antoniou A, Pharoah PDP, Narod S et al: Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case series unselected for family history: a combined analysis of 22 studies. Am J Hum Genet 2003; 72: 1117–1130.

Thompson D, Easton DF, The Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium: Cancer incidence in BRCA1 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002; 94: 1358–1365.

Ford D, Easton DF, Stratton M et al: Genetic heterogeneity and penetrance analysis of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in breast cancer families. Am J Hum Genet 1998; 62: 676–689.

Fry A, Cull A, Appleton S et al: A randomised controlled trial of breast cancer genetics services in South East Scotland: psychological impact. Br J Cancer 2003; 89: 653–659.

Torrance N, Mollison J, Wordsworth S et al: Genetic nurse counsellors can be an acceptable and cost-effective alternative to clinical geneticists for breast cancer risk genetic counseling. Evidence from two parallel randomised controlled equivalence trials. Br J Cancer 2006; 95: 435–444.

Douglas FS, O'Dair LC, Robinson M, Evans DG, Lynch SA : The accuracy of diagnoses as reported in families with cancer: a retrospective study. J Med Genet 1999; 36: 309–312.

Hopwood P, Wonderling D, Watson M et al: A randomised comparison of UK genetic risk counselling services for familial cancer: psychosocial outcomes. Br J Cancer 2004; 91: 884–892.

Henriksson K, Olson H, Kristoferson U : The need for oncogenetic counseling. Ten years' experience of a regional oncogenetic clinic. Acta Oncol 2004; 43: 637–649.

Steel M, Smyth E, Vasen H et al: Ethical, Social and economic issues in familial breast cancer: a compilation of views from the E.C. Biomed 11 Demonstration Project. Dis Markers 1999; 15: 125–131.

Kinmonth AL, Reinhard J, Bobrow M, Pauker S : The new genetics. Implications for clinical services in Britain and the United States. BMJ 1998; 316: 767–770.

Drummond MF, O'Brien B, Stoddart GL, Torrance G : Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

National Institute for Health Clinical Excellence: Appraisal of new and existing technologies: interim guidance for manufacturers and sponsors, 2004.

Aitken J, Bain C, Ward M, Siskind V, Maclennan R : How accurate is self-reported family history of colorectal cancer? Am J Epidemiol 1995; 141: 863–871.

Sijmons RH, Boonstra AE, Reefhuis J et al: Accuracy of family history of cancer: clinical genetic implications. Eur J Hum Genet 2000; 8: 181–186.

Acknowledgements

The Department of Medical Genetics is funded by NHS Grampian. Sarah Wordsworth is funded by a Department of Health Fellowship Award. We thank Pat Yudkin (University of Oxford) for statistical advice. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and are not attributable to the funding body.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gregory, H., Wordsworth, S., Gibbons, B. et al. Risk estimation for familial breast cancer: improving the system of counselling. Eur J Hum Genet 15, 1139–1144 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201895

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201895

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The use of genealogy databases for risk assessment in genetic health service: a systematic review

Journal of Community Genetics (2013)

-

A study of the practice of individual genetic counsellors and genetic nurses in Europe

Journal of Community Genetics (2013)