Key Points

-

A national study of satisfaction about dental services in the UK.

-

Most people in Britain are satisfied with dental services. However, about one in 10 have felt like or actually have complained about dental services in the past.

-

One in three did not know to whom to complain if they were dissatisfied about dental services.

-

Knowledge about the complaints procedure process appears fragmented.

Abstract

Objectives To determine satisfaction with dental care services among the UK adult population, and to assess their knowledge regarding the dental complaints procedure.

Methods A national survey involving a multi-stage random sampling procedure with face-to-face home interviews of 5,385 UK residents was conducted in 1999.

Results The response rate was 69% and 3,739 adults took part in this study. Majority of people (89%) were satisfied with the quality of care they received. Only 2% (76) had actually complained, although 10% (388) had felt like complaining in the past. One third (32%, 1,188) did not know to whom to complain if they had a problem. Among those who knew whom to contact, over a third (36%, 1,359) would contact somebody outside the practice, while another third (31%, 1,169) would contact their dentist or dental practice.

Conclusion Overall most people are satisfied with the quality of dental care they receive. However, 2% have complained and 10% have felt like complaining about their dentist/ dental care. In general, knowledge of the complaints procedure and whom to contact appears fragmented.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

At the time of heightened consumer rights and awareness surrounding health related issues, dental complaints appear to be particularly significant today. With the current ongoing debate quoted in a recent survey by a national magazine1 (2002); of the 155 people interviewed from a non-random sample, more than two-thirds who complained were dissatisfied with the way their complaints were dealt with.1 Some of the common reasons cited for making a complaint within dentistry are: poor quality of treatment and mistakes, service and attitude of staff and excessive charges.1,2

Dental complaints made by patients may cause a great deal of worry and stress among dentists.3,4 Dissatisfaction and complaints may result in patients changing their dentist, which might have ramifications in terms of the family and friends' perceptions of the dental practice.5 Furthermore, in the ever-increasing medico-legal environment surrounding dentistry in Britain today, patients' complaints that are not dealt with locally in the practice could result in long and costly legal proceedings.6

For the profession it is important to promote high standards of professional conduct among dentists.7 The British Dental Association (BDA) believes that professional self-regulation, with significant public input, is the best means to ensure protection of the public against the minority of cases of dental negligence.8 Currently, patients in England needing help with a complaint should contact the Local Community Council, while in Scotland the Local Health Council and in Northern Ireland the Health and Social Services. All complaints of 'serious professional misconduct' whether NHS or private should be taken to the General Dental Council (GDC).7

In an era of clinical governance and patient partnership in delivering high quality oral healthcare, it is necessary that patients' concerns are dealt with appropriately.9 The GDC and BDA take very seriously any cases of unsatisfactory treatment that come to light.10 The National Health Service has repeatedly reiterated its support for providing information to the public to channel their concerns and to act on their suggestions swiftly and judiciously.11 An extensive network with a lot of investment has been developed in providing advice and advocacy for patients and also in evaluating the existing complaints system.12 Despite the obvious importance of complaints and complaint procedures in dentistry for both the profession and the public it remains an area under researched.

Aims

This study aimed to determine satisfaction with the quality of dental care among the UK adult population, to determine whether they have actually complained or felt like complaining about the dental care they received, and to assess their knowledge about complaints procedures. In addition, to identify socio-demographic (age, gender, social class, area-of-residency) and dental service factors (time and reason for last dental visit, type of dental practice) that might have a bearing on complaints within dentistry.

Sample and Methods

Study population

The Office for National Statistics Omnibus Surveys of Great Britain conducted this study over a two-month period between June and July in 1999. A multistage random sampling technique over the two-month period was employed. The sampling frame was selected based on the British Postcode Address File (PAF). The PAF contains a list of household addresses in the UK, and is the most complete list of addresses in Britain.

One hundred postal sectors were first selected, then 30 addresses were randomly selected for both months within each postal sector. Of the 6,000 selected addresses, only 5,385 were eligible addresses. The six hundred and fifteen ineligible addresses included new and empty premises. Trained interviewers carried out face-to-face interviews with an adult respondent (aged 16 or older) at all the eligible addresses.

Data collection

Respondents were interviewed about when they last visited the dentist, why they last visited the dentist, and method of payment they used the last time they visited the dentist (whether private or NHS). A global satisfaction question about the quality of dental care they received was asked and two questions specifically related to complaints: whether they ever felt like or actually complained about their dentist and whom they would first contact if they were making a complaint (Appendix 1). In addition, information was collected about respondents' socio-demographic characteristics: age, gender, area of residency and social class (based on the Registrar's General Classification).

Data analysis

The data was weighted to correct for the unequal probability of selection caused by interviewing only one adult per household (the weight was calculated by dividing the number of adults in the sampled households by the average number of adults per household). Response rate and frequency distribution of responses relating to questions about satisfaction and complaints were produced. Variations in the views of the public about satisfaction and complaints in dentistry were explored in relation to socio-demographic and dental service factors in bivariate analysis. Following on, a series of regression (logistic) analyses were conducted to identify independent predictors of satisfaction and issues about complaints.

Results

Response rate

The overall response rate for the Omnibus Surveys was 69% with 3,739 people participating in the study. Of the 5,385 eligible addresses that were selected, 22% refused to take part in the study and 9% of the respondents could not be contacted, as there was no response at their homes following three visits by the interviewers. The profile of the study group is presented in Table 1.

Satisfaction with dental services

Overall 3,328 (89%) people were satisfied with the quality of care they received at their dentist. Among these over half (63%, 2,087/3,328) were 'very satisfied' and over a third (37%, 1,241/3,328) 'satisfied'. On the other hand, among 272 (8%) people who were dissatisfied with the quality of care they received, one third (37%, 100/272) were very dissatisfied (Table 2).

Bivariate analysis revealed that satisfaction with the quality of care received at the dentist was associated with three socio-demographic and dental service factors: age (P=0.01), time since last dental visit (P<0.001), and reason for last dental visit (P<0.001). Having controlled for other variables in the regression analysis, these factors (age, time and reason for last dental visit) remained independently associated with perceived satisfaction with quality of dental care (Table 3). Younger people (16-64 years) were less satisfied with the quality of care they received at their dentist compared to older people (65 and older), (OR=1.75, 95% CI 1.24, 2.48, P=0.002). Those who reported attending the dentist within the past year were less likely to be dissatisfied with dental services compared to those who claimed they last attended the dentist over a year ago (OR=0.56, 95%CI 0.43, 0.74, P<0.001). Problem-motivated dental attenders were more than twice as likely to be dissatisfied with the quality of dental service compared to non-pain motivated dental attenders (OR=2.24, 95%CI 1.64, 3.05, P<0.001).

Complaints: felt like or actually complained

Ten per cent (388) claimed that they felt like complaining about their dentist in the past and 2% (76) claimed that they actually did complain about their dentist. Forty-eight people (1%) declined to answer the question (Table 2).

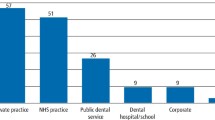

Bivariate analysis identified associations between complaints (felt like or actually complained) and several socio-demographic and dental service factors: age (P<0.001), area-of-residency (P<0.001), reason for last dental visit (P<0.001), method of payment for dental services (P=0.004). These factors remained evident in the regression analysis (Table 3). Younger people (aged 16-64) were 1.58 times more likely to have felt like or actually complained about dental services compared to older people (aged 65 or older), (OR=1.58, 95%CI 1.20, 2.07, P=0.001). Those who lived in the south were 1.5 times more likely to have felt like or actually complained compared to those living elsewhere in the UK (OR=1.46, 95%CI 1.18, 1.80, P<0.001). Problem-motivated dental attenders were almost twice as likely to have felt like or actually complained compared to non-problem motivated dental attenders (OR=1.74, 95%CI 1.33, 2.27, P<0.001). Private dental services users were 1.27 times more likely to have felt like or actually complained compared to NHS service users (OR=1.27, 95%CI 1.02, 1.58, P=0.031).

Complaints: Who they would contact first?

Thirty two per cent (1,188) claimed they would not know whom to contact if they were to complain about their dentist. Among those who claimed they knew who they should contact if they were to complain about their dentist (68%, 2,528), approximately half of these (46%, 1,169/2,528) said they would first complain within the practice either to the dentist, principal of the practice, practice manager or receptionist. Among those who claimed they would first contact an agency outside the dental practice if they were to complain (36%, 1,359); 40% (539/1,359) of these claimed they would complain to the local health authority, another 40% (548/1,359) would contact the GDC or BDA, while the remaining 20% (272/1,359) would first contact other agencies such as citizen's advice bureau, medical doctors or solicitors (Table 2).

In bivariate analysis, knowledge about who to contact if they were to complain about dental treatment or their dentist was associated with age group (P<0.001), gender (P<0.001), social class background (P<0.001), as well as service related factors: time since last dental visit (P<0.001) and method of payment (P<0.001).

These factors remained independently associated with knowledge about to whom to complain about dental treatment or the dentist in regression analysis (Table 3). Younger people (aged 16-64) were 1.45 times more likely to claim that they would know whom to contact if they were to complain about their dentist/ dental care compared to older people (aged 65 or older), (OR=1.45, 95%CI 1.22, 1.72, P<0.001). Women were less likely to claim that they would know whom to contact if they were to complain about their dentist/dental care compared to men, (OR=0.83, 95%CI 0.72, 0.96, P=0.02). People from social class backgrounds I, II, IIINM were 1.53 times more likely to claim that they would know whom to contact if they were to complain about their dentist/ dental care compared to those from social class IIIM, IV, V (OR=1.53, 95%CI 1.31, 1.78, P<0.001). Those who reported visiting the dentist within the past year were 1.52 times more likely to claim that they would know whom to contact if they were to complain about their dentist/ dental care compared to those who reported visiting their dentist over a year ago (OR=1.52, 95%CI 1.30, 1.78, P<0.001). Private dental service users were 1.20 times more likely to claim that they would know whom to contact if they were to complain about their dentist/ dental care compared to NHS service users (OR=1.20, 95%CI 1.02, 1.41, P=0.03) (Table 3).

Discussion

This national study provides valuable up-to-date information about complaints and satisfaction within dentistry from a public perception, involving a random sample of over 5,000 adults in Britain. The study was limited to determining what proportion were satisfied, felt like or actually did complain about their dentist/ dental treatment, but did not aim to explore the common reasons cited by those making a complaint or why they were dissatisfied. However, it did seek to identify associated factors (socio-demographic and service related) that might provide an insight into the complex issues about complaints and satisfaction.

The response rate was relatively high (69%) and comparable with the response rates from other national oral health surveys.13 As with all studies there are possible bias effects as a result of non-participation. However, the socio-demographic profile of the participants is comparable with census information, suggesting that the study group is representative of the UK adult population.14

The majority of the people (89%) reported to be satisfied with the quality of care they received, similar to British Dental Association independent polls, which have shown that as many as nine out of ten people have confidence in the treatment they receive.15 Likewise, satisfaction with dental services is similar to satisfaction with in-patient NHS care.16 Dissatisfaction was higher among younger people, problem motivated and irregular attendees. Discontent about dental services is likely to be a key factor that influences dental service use.5

Very few (12%) people had felt like or actually complained about their dentist, this supports the findings from other studies that have reported that very few practitioners have to deal with complaints from patients.10 Younger people, those living in the South and private dental service users were more likely to have felt like or actually complained about their dentist/ dental treatment suggesting that these groups are likely to demand and expect a high quality of care.

A very important issue we looked at was knowledge regarding the complaints procedure and as many as one in three people were not sure whom to contact if they were to complain. This would suggest a substantial lack of knowledge by the public on appropriate channels to use in complaining about inappropriate standards of dental care. It is essential that access to information and advice be made available to all to ensure that the public can inform and provide valuable feedback about quality of care.7 It is important that socio-demographic disparities in knowledge about the complaints process be addressed and that similar knowledge about the complaints procedures is available for both private and NHS dental service. Encouragingly, regular users of dental service were more likely to know whom to contact if they were to complain about their dentist/ dental treatment than irregular dental attenders (those who reported attending the dentist over a year ago) which may reflect recent initiatives directed at informing patients of the dental complaints procedures.11,12

Among those who claimed they would know whom to contact if they were to complain about their dentist (two-thirds), approximately half claimed they would first try and deal with the complaint in the dental practice. Clearly appropriate training for all dental personnel about handling complaints (including receptionist and practice managers) is an essential element to solving the problem and preventing further consequences.17

Interestingly, if the public were to contact an agency outside the dental practice to complain, then the majority would either complain to the local health authority or to governing dental bodies. Less frequently they would contact other agencies like a solicitor or medical doctor first. This suggests partial recognition but not universal knowledge of a complaints procedure within dentistry. The British Dental Association does agree in principle to have a single complaints system but emphasises that such a system may be more complex than it first appears because of the multifactoral nature of how complaints arise and thus there may be no simple or single way to deal with them.10

Conclusion

Overall most people in Britain are satisfied with the quality of dental care they receive (9 out of 10), only 2% have reported complaining about the care they received and 10% have reported to have felt like complaining about their dentist/ dental care. Knowledge of the complaints procedure and whom to contact appears fragmented if they were to complain about dental care.

References

www.which.net. Inadequate complaints procedure for dentists leaves consumers toothless. Press Release, Dental complaints, Which? Magazine, 03 January 2002.

Calnan M, Dickinson M, Manley G . The quality of general dental care: public and users' perceptions. Quality health care 1999; 8: 149– 153.

Humphris GM, Cooper CL . New stressors for GDPs in the past ten years: a qualitative study. Br Dent J 1998; 185: 404– 406.

Shugars DA, DiMatteo MR, Hays RD, Cretin S, Johnson JD . Professional satisfaction among Californian general dentists. J Dent Educ 1990; 54: 661– 669.

O'Shea RM, Corah NL, Ayer WA . Why patients change dentists: practitioners' views. J Am Dent Assoc 1986; 112: 851– 814.

Mellor AC, Milgrom P . Prevalence of complaints by patients against general dental practitioners in Greater Manchester. Br Dent J 1995; 178: 249– 253.

General Dental Council. Maintaining professional standards. Professional conduct, 8.2 to 8.26. 2001

http://www.bda-dentistry.org.uk. Self-regulation. BDA News.

Crossley ML, Blinkhorn A, Cox M . What do our patients really want from us? Investigating patients perceptions of the validity of the Charternark criteria. Br Dent J 2001; 190: 602– 606.

British Dental Association Press and Parliamentary News. http://www.bda-dentistry.org.uk. Press release PR01.02. British Dental Association statement on Dental Complaints Procedure, January 2002.

NHS complaints procedure-National Evaluation document. Department of Health October 2001.

Locker D . Response and nonresponse bias in oral health surveys. J Public Health Dent 2000; 60: 72– 81.

British Dental Association. Press and Parliamentary Department. BDA: Dentistry facts, Harris poll commissioned by the BDA on how people feel about their dentist. September 2001.

Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Bruster S, Richards N, Chandola T . Patients' experiences and satisfaction with health care: results of a questionnaire study of specific aspects of care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002; 11: 335– 339.

Davies LG, Winstanley RB . The introduction of dental team education. Br Dent J 1997; 182: 436– 439.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bedi, R., Gulati, N. & McGrath, C. A study of satisfaction with dental services among adults in the United Kingdom. Br Dent J 198, 433–437 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4812198

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4812198

This article is cited by

-

Satisfaction with dental care services in Great Britain 1998–2019

BMC Oral Health (2022)

-

Satisfaction with healthcare services among refugees in Zaatari camp in Jordan

BMC Health Services Research (2021)

-

Dental complaints procedures

British Dental Journal (2005)