Key Points

-

Isolated congenital alveolar synechiae is a rarely seen disease.

-

In the early stages this can be treated by simple methods.

-

In late stages temporomandibular joint ankylosis arises.

Abstract

Congenital alveolar synechiae is rarely seen as an isolated disease. It is generally observed together with various syndromes such as Van der Woude and cleft palate lateral alveolar synechiae syndrome, and is concomitant with other anomalies in the maxillofacial or other regions of the body. Prior to this case report, eight cases of isolated congenital alveolar synechiae have been reported. This paper reports a case of isolated congenital alveolar synechiae in a 10-month-old baby girl. The report concentrates on the clinical features of isolated congenital alveolar synechiae, the likely aetiological causes and the treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Case report

A 10-month-old baby girl suffering from restricted mouth opening was brought by her family to our clinic. At clinical examination it was established that the patient's mouth opening was only 5–6 mm because of bilateral intermaxillary fibrous adhesions of around 1.5 cm wide and 3mm thick on the line of the primary molars (Fig. 1).

No useful information was obtained from the family's medical history. The mother had undergone a healthy pregnancy and there was no account of any illness, trauma or drug use. The baby was the family's first child, and there was no history of cleft palate or other anomaly in close relatives. The baby had been born vaginally, and no other anomaly than alveolar synechiae had been determined during or after birth.

No anomalies were revealed during radiographic examination. Following consultation with the paediatric clinic, no other congenital anomaly was identified.

Treatment

Following the injection of a low dosage of lidocaine to the regions in which the adhesions were located, the fibrous bands were excised by separation with surgical scissors. Together with a minimal level of haemorrhage it was seen that mouth opening immediately increased, with an interincisal opening of some 20 mm being achieved (Fig. 2). This intra-operative finding was of a nature to support the healthy appearance of the TMJ radiographically. No post-operative complications were encountered.

Comment

Synechiae are adhesions between anatomic structures.1 Congenital adhesions (synechiae) rarely occur between different parts of the oral cavity.2 While these synechiae most commonly arise between the upper and lower alveolar ridges (syngnathism) or between the tongue and margins of the palate or maxilla (glossopalatal ankylosis); synechiae arising from the lower lip, the floor of the mouth, or at the oropharyngeal isthmus have also been described.2 These may consist of membranes or bands of epithelium supported by various amounts of connective tissue, and possibly even muscle or bone.2 Extreme alveolar synechiae rarely occur as an isolated anomaly; they are almost always accompanied by one or more additional congenital defects, such as cleft palate, cleft lip, microglossia, micrognathia, temporomandibular joint disorders or lip anomalies. Cleft palates are the deformities most frequently seen with alveolar synechiae.1,2,3,4 Alveolar synechiae in conjunction with a cleft palate is known as lateral alveolar synechiae syndrome.1,2,3

Congenital alveolar synechiae is a pathological condition rarely seen in isolation. In a study in which they reviewed fifty cases of alveolar synechiae reported between 1990 and 1993 and also submitted two additional cases of congenital alveolar synechiae, Gartlan et al.2 reported that isolated congenital alveolar synechiae without any additional anomaly was observed in only seven cases.2 In our review of the literature, a further nine cases of congenital alveolar synechiae have been reported in addition to the 52 cases of alveolar synechiae considered by Gartlan et al.5,6,7,8,9 It was reported that only one of these was isolated congenital alveolar synechiae,9 the other eight being seen together with such syndromes as Van der Woude, cleft palate alveolar synechiae and oromandibular limb hypogenesis syndrome.5,6,7,8

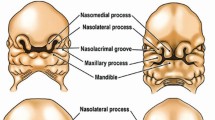

The cause of synechiae is still unknown. During the seventh to eighth week of embryological development, the alveolar ridges, tongue and palatal shelves are in contact with each other. The ensuing palatal closure depends on downward contraction of the tongue. When the tongue protrudes from the mouth as a result of medial movements of the oral cavity walls, it prevents the alveolar ridges from fusing. Genetic, teratogenic, or mechanical insults during this critical stage may lead to periods of close, quiescent contact between oral structures, and this predisposes to abnormal fusion.9 Trauma late in pregnancy, abnormality of the stapedial artery, and teratogenic agents are other reported aetiological factors.10

Mathis11 postulated that such adhesions were remnants of the buccopharyngeal membrane. Hayward and Avery12 thought the adhesions developed as a result of contact between the epithelium of the gums or the palatine shelves and the floor of the mouth. Fuhrmann et al.13 reported that five family members had cleft palates and synechiae, one having a cleft palate without synechiae, and one transmitted the gene but did not express it. Sternberg et al.14 reported a newborn baby with congenital bilateral complete fusion of the gums and the temporomandibular joint. Sternberg et al.14 suggested that the probable sequence of events in this baby was:

-

1

Fusion of the gums

-

2

Formation of the posterior cleft palate caused by failure of the tongue mass to drop fully because of the micrognathia and the fused gums, and

-

3

Fibrous ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint caused by a lack of movement of the mandible.

We are of the opinion that in our case, since the fibrous adhesions were of a length which permitted a 5–6 mm opening, they prevented the formation of a cleft palate and TMJ ankylosis in the latter phases of embryonic development. In addition, the absence of an additional congenital anomaly and there being no observation of such an anomaly in the family members made us think that a genetic transmission is out of the question.

Gartlan et al.2 speculated that major congenital synechiae of the oral cavity constitute a clinically confusing spectrum of abnormalities. On the basis of clinical data, they proposed two categories:

-

1

Abnormalities secondary to persistence of the buccopharyngeal membrane, and

-

2

Abnormalities secondary to the formation of ectopic membranes.

An ectopic membrane results from abnormal fusion and can be sub-classified as a subglossopalatal membrane, glossopalatal ankylosis or syngnathia.2

In the present case, the cause of the synechiae seems to be abnormality secondary to the formation of ectopic membranes. The adhesions were separated with excision after the administration of local anaesthesia. Simple surgical division of the adhesions was necessary to allow normal feeding, to avoid upper airway obstruction and to allow normal mandibular function and growth.

This report describes an extremely rare case of alveolar synechiae with no congenital abnormalities and the necessary treatment provided.

References

Dinardo NM, Christian JM, Bennet JA, Bennet JA . Cleft palate lateral synechiae syndrome Review of the literature and case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1989; 68: 565–566.

Gartlan MG, Davies J, Smith RJ . Congenital oral synechiae. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1993; 102: 186–197.

Verdi GD, O'Neal B . Cleft palate and congenital alveolar synechiae syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg 1984; 74: 684–686.

Dalal M, Davison PM . Cleft palate congenital alveolar synechiae syndrome: Case report and review. Br J Surg 2002; 55: 256–257.

Denion E, Capon N, Martinot V, Pellerin P . Neonatal permanent jaw construction because of synechiae and Pierre Robin sequence in a child with van der Woude syndrome. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2002; 39: 115–119.

Knoll B, Karas D, Persing JA, Shin J . Complete congenital bony syngnathia in a case of oromandibular limb hypogenesis syndrome. J Craniofac Surg 2000; 11: 398–404.

Haramis HT, Apesos J . Cleft palate and congenital lateral alveolar synechiae syndrome: case presentation and literature review. Ann Plast Surg 1995; 34: 424–430.

Ergen C, Sayan NB . Van der Woude syndrome (report of a case) Ankara Üniv Dishek Fak Derg 1985; 12: 163–169.

Haydar SG, Tercan A, Uçkan S, Gürakan B . Congenital gum synechiae as an isolated anomaly: A case report. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2003; 28: 81–84.

Laster Z, Temkin D, Zarfin Y, Kushnir A . A complete bony fusion of the mandible to the zygomatic complex and maxillary tuberosity: case report end review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2001;30: 75–79.

Mathis VH . Über einen fall von ernäunng-sschwierigkeit bei connataler syngnathie. Deutsche Zahnäzliche Zeitschrift 1962; 17: 1167–1171.

Hayward JR, Avery JK . A variation in cleft palate. J Oral Surg 1957; 15:320, 24.

Fhurmann W, Koch F, Scheweckendick W . Autosomol dominante Vererbung von Gaumenspalte and synechien zwischen gaumen und mundboden oder zunge. Humangenetik 1972; 14: 196–203.

Sternberg N, Sagher U, Golan J, Eidelman AI, Ben-Hur N . Congenital fusion of the gums with bilateral fusion of the temporomandibular joints. Plast and Reconstruc Surg 1983; 72: 385–387.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tanrikulu, R., Erol, B., Görgün, B. et al. Congenital alveolar synechiae — a case report. Br Dent J 198, 81–82 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4811971

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4811971

This article is cited by

-

Congenital Maxillomandibular Syngnathia: Review of Literature and Proposed New Classification System

Journal of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery (2021)

-

Congenital fusion of the jaws

The Indian Journal of Pediatrics (2007)