Key Points

-

SARS is a highly infectious and rapidly progressive form of atypical pneumonia caused by a newly identified strain of coronavirus (SARS-CoV).

-

Diagnosis is based on clinical findings, epidemiology and exclusion from other pneumonias and is confirmed by a positive seroconversion. There is as yet no definitive treatment protocol.

-

Symptoms may be similar to other less infective or morbid diseases and over one quarter of those affected have been unsuspecting healthcare workers.

-

HCW must be familiar with the clinical features and case definitions of SARS to assist in the screening of the disease and prevention of spread.

-

Surveillance for possible SARS is recommended and control of the epidemic depends on early identification and isolation of carriers and effective infection control and public health measures.

Abstract

The health profession faces a new challenge with the emergence of a novel viral disease Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), a form of atypical pneumonia caused by a coronavirus termed SARS-CoV. This highly infectious disease has spread through 32 countries, infecting more than 8,400 patients with over 790 deaths in just over 6 months. Over one quarter of those infected were unsuspecting healthcare workers. The major transmission mode of SARS-coronavirus appears to be through droplet spread with other minor subsidiary modes of transmission such as close contact and fomites although air borne transmission has not been ruled out. There is as yet no definitive treatment protocol. Although the peak period of the outbreak is likely to have passed and the risk of SARS in the UK is therefore assessed to be low, the World Health Organisation has asked all countries to remain vigilant lest SARS re-emerges. Recent laboratory acquired cases of SARS reported from Taiwan and Beijing, China are a testimony to this risk. Until reliable diagnostic tests, vaccine and medications are available, control of SARS outbreaks depends on close surveillance, early identification of index cases, quick isolation of carriers and effective infection control and public health measures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Yet another emerging disease is threatening to take a foothold on the global populace. This novel disease entity, termed Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), is an atypical pneumonia that is likely to have originated in the Guangdong province of Southern China in the fall of 2002.1,2 As of August 2003 more than 8,400 SARS cases and 916 deaths have been reported worldwide from 32 countries.3 The brunt of the disease has thus far been borne by the East, especially China (including Hong Kong) and Singapore whilst the West, except for Canada, still remains relatively unscathed with only sporadic infections brought home by travellers to affected areas. During this period the UK had a total of four probable cases, one of which had a confirmed exposure to the SARS coronavirus. All four had fully recovered and there was no secondary spread.4 The World Health Organisation (WHO) has announced recently that the peak period of the outbreak is likely to have passed and the associated dwindling in the morbidity and mortality rates is a testimony to this. In countries like the UK the risk of SARS is therefore assessed to be low. However, WHO has asked all countries to remain vigilant. The Health Protection Agency (HPA) of the UK also advised that the situation in the UK may have to be re-assessed if SARS does re-emerge.5 And indeed a confirmed case of SARS coronavirus infection was reported in Singapore as recently as September 2003 although the infection was transmitted through laboratory contamination and not via the community.6

We provide in Part I of this paper a brief account of the epidemiology, virology and clinical features of SARS, the general infection control measures and public health concerns. Part II will provide a detailed account of infection control measures that may be applied in the general dental practice, especially in the SARS-affected areas. There is a virtual explosion of knowledge on SARS, the virus, the clinical features of the disease and its prevention. Hence the readers are urged to keep current by periodic referral to the websites at the Health Protection Agency of the UK (http://www.hpa.org.uk/infections/topics_az/SARS/), Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, USA (http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/sars/) and the World Health Organization (http://www.who.int/en/).

The disease and virology

SARS is rapidly progressive and highly infectious. Although less contagious than influenza it is much more so than other circulating viruses such as the human immunodeficiency virus. In fact SARS is the first severe and readily transmissible new disease to emerge in the twenty-first century. Most SARS infections occur after close exposure to the index case as in household contacts but casual social contact may transmit the disease on occasions. The spread amongst front line healthcare workers (HCWs) has been one of the most disconcerting aspects of SARS. Currently, one quarter to one third infected are unsuspecting HCWs who fought to save the lives of patients without adequate barrier protection.1,7 International travel through major transportation hubs such as Hong Kong and Singapore has facilitated the spread of the disease to all corners of the globe within a short time span.1,8

HPA definitions are given in Box 1

The viral aetiology

The disease is caused by a coronavirus now termed the SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV) 9,10, a strain not previously seen in humans (Fig. 1). Its unique genetic composition has led to its categorisation into a separate group, for instance from those that cause common cold in humans and other, animal coronaviruses (eg murine and avian). Structurally, it is an enveloped, single stranded RNA (80-100 nm) virus covered by spike-like projections, resembling a crown, when viewed electron microscopically, hence its name.11 Although the genome organization of SARS-CoV is similar to that of other coronaviruses, they are not closely related.12

In one study RNA from the SARS-CoV was found in half of the nasopharyngeal specimens from SARS patients but in no specimens from 40 patients with other respiratory illnesses.13 Rising antibody titres to the virus were noted in all 32 SARS patients from whom second serum specimens were obtained. Viral RNA was found in 10 of 18 faecal samples from SARS patients. Further, a SARS-like disease has been reproduced in monkeys through inoculation of the SARS-CoV.10 Thus all of Koch's postulates (see Box 2) have been fulfilled with regard to the viral aetiology of SARS. Finally, and remarkably, within a short period of 3 months, the entire viral genome has been sequenced and is freely available for scientific use through the worldwide web.

Mode of transmission

The major transmission mode of SARS-CoV appears to be through droplet spread with other minor subsidiary modes of transmission such as close contact, fomite (an inanimate object which, when contaminated with a pathogen, can transfer the pathogen to a host) or even faecal contamination.1,7,14,15 Airborne transmission has not been ruled out.16

Signs and Symptoms 1,2,7,17

There is an incubation period of usually 2-10 days. The first symptoms are fever (> 38°C) in 100% of patients and malaise (in 70%) followed by non-productive cough (in nearly 100%) and dyspnoea (in 80%). Chills, rigors, headache, malaise, diarrhoea and myalgia are common whilst rhinorrhoea and sore throats are uncommon (in fewer than 25%).

Radiological signs may be seen at the onset of fever and chest radiographs reveal consolidation that progressively increases in size, predominantly in the lower lung fields; pleural effusions are absent. Lung biopsy reveals interstitial inflammation. Oxygen saturation is reduced in some one half of patients. Laboratory testing reveals leukopaenia, lymhocytopaenia and thrombocytopaenia.

Diagnosis and treatment

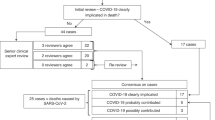

Specialist laboratories eg the Health Protection Agency (HPA) National Influenza Reference Laboratory at Colindale perform diagnostic tests which detect the virus (cell culture and reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction, RT-PCR) or antibody (immuno fluorescent antibody and ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays) (see Box 3 for diagnostic test definitions).18 However, the duration of detectable viraemia or viral shedding is unknown, leading to false negative results when samples are not taken at the right time. Moreover, the collection of nasopharyngeal aspirate (the specimen of choice) induces reflex actions from the patients that generate aerosols, that exposes the attending HCW to a high risk of infection.19

Paired serology, ie seroconversion, obtained on day 1 and > 21 days after onset of symptoms, is considered by WHO and HPA to be the diagnostic gold standard20 but it is only useful for confirmation of the diagnosis (or exclusion of the diagnosis if negative) and not for screening purposes. Diagnosis is thus based on clinical findings, epidemiology and exclusion from other pneumonias and is confirmed by a positive seroconversion.21,22 There is no definitive treatment and empirical regimes differ amongst countries and may include the use of antibiotics, anti-virals and steroids.1,23,24 Severe cases require mechanical ventilation in intensive care units.1,7 Several groups have reported uncontrolled trials of antiviral (ribavirin) and steroids, the efficacy of which has not been resolved as yet. According to some, delay in treatment beyond a window period of first 8 days of symptom onset is associated with worse prognosis. Fatality rate ranges from below 1% in persons under 24 years of age to more than 50% in persons over 65 years; The median fatality rate is 13%.25

Until reliable diagnostic tests, vaccine and medications15,26 are available, surveillance for possible SARS as recommended by HPA5 and control of the epidemic depends on early identification and isolation of carriers (symptomatic or asymptomatic), effective infection control and public health measures.

Case definitions

The case definitions provided by HPA5 are in line with the WHO definitions:

Clinical case definition

A severe respiratory illness with a history of fever ≥ 38°C:

and symptom(s) of lower respiratory tract illness (cough, difficulty breathing, shortness of breath)

and radiographic evidence consistent with pneumonia or respiratory distress syndrome (RDS)

and no alternative diagnosis to explain the illness.

Possible case

A person fulfilling the clinical case definitions and who, within 10 days of onset of illness, has a history of travel to an area classified by WHO as a potential zone of re-emergence of SARS

or

two or more healthcare workers/staff/patients/visitors in (or linked to) the same facility developing symptoms within the same 10-day period.

Probable case

A possible case with preliminary laboratory evidence of SARS-CoV infections based on a single positive antibody test or PCR for SARS-CoV

Confirmed case

A possible case with confirmed laboratory findings based on repeat positive PCR findings or seroconversion by ELISA or IFA.

Identification of such cases should be immediately reported to local and national health authorities eg Health Protection Agency, Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre in the UK.

Infection control and public health measures

The mainstay of preventing SARS-CoV infection in community and clinical settings is to institute appropriate infection control measures.

We review below, in this context, the available infection control measures and the possible modification of these in view of the SARS outbreak. Some of the guidelines described in Part 2 of this paper are modifications that we had adopted at the time of the SARS crisis. Hence the implementation of these is necessarily dictated by the disease prevalence and proximity in various geographic areas, and should be flexibly exercised.

Universal and Standard Precautions

In 1985, the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) introduced the concept of universal precautions whereby human blood and certain body fluids (eg saliva) are treated as if infective for bloodborne pathogens. Because carriers of some infections may not be readily identifiable the same infection control procedure is universally applied to all patients.27 The philosophy, recommendations and protocols are detailed elsewhere.28,29,30

In brief, these include measures to protect:

-

1

Healthcare workers from contracting the disease from the patient directly (eg screening, the use of personal protection, immunization) or indirectly (eg frequent hand washing, barrier technique).

-

2

Patients from cross-infection eg strict instrument sterilisation and storage protocols, barrier technique, and delineation of work areas.

-

3

Laboratory personnel by proper disinfections of all laboratory items and the proper handling of biopsy specimens.

-

4

Immunocompromised patients who are more susceptible to infections and are particularly at risks from pathogens in the dental unit waterline.

-

5

General public by proper disposal of clinical waste.

Standard precautions

The concept of standard precautions, introduced by the CDC in 1996, incorporates all the features of universal precautions against bloodborne pathogens (eg HIV, hepatitis viruses). In addition it aims to prevent the transmission of airborne and epidemiologically important pathogens such as tuberculosis. As the SARS-CoV appears mainly to spread through the airborne route the prevention of contact and inhalation of infectious droplet or air-borne particles and the use of standard precautions is more appropriate.31,32 This is in agreement with guidelines from the HPA, UK which recommended that infection control measures against SARS be based on those taken against respiratory infections such as tuberculosis and influenza.33

The community infection control measures are listed in Box 4. Detailed community infection control guidelines given by HPA are available at http://www.hpa.org.uk/infections/topics_az/SARS/primarycare.htm

Conclusion

The newly emerged SARS-CoV caused significant morbidity and mortality in a relatively short period of time especially in the Asian region. Researchers worldwide are striving hard to unravel the mystery of its virology including the reservoirs of infection, pathology, modes of spread and finally an effective vaccine. A definitive screening and treatment protocol for the infection is yet to be determined. Until then the public healthcare workers including the dental professional must rely on preventive measures, particularly screening and astute infection control in the event of its possible re-emergence.

The implications of SARS for the general dental practitioners will be discussed in the second part of this paper.

References

Poutanen SM, Low DE, Henry B et al. Identification of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Canada. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 1995–2005.

Tsang KW, Ho PL, Ooi GC et al. A cluster of cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 1977–1985.

Department of Communicable Disease Surveillance and Responses (CSR). Summary table of SARS cases by country, 1 November 2002 - 7 August 2003. Geneva: World Health Organisation. Aug 2003 http://www.who.int/csr/sars/country/2003_08_15/en/Lastretrievalon18thSept2003.

Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre (CDSC). Background information. London: Health Protection Agency (HPA). Reviewed on 1st September 2003. http://www.hpa.org.uk/infections/topics_az/SARS/background.htm Last retrieval on 20th Sept 2003.

Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre (CDSC). Guidance on identification, reporting, and management of SARS patients in the UK in the post-outbreak period. London: Health Protection Agency (HPA). Reviewed on 15th August 2003. http://www.hpa.org.uk/infections/topics_az/SARS/casedef.htm Last retrieval on 20th Sept 2003.

Department of Communicable Disease Surveillance and Responses (CSR). Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in Singapore. Geneva: World Health Organization. 10th Sept 2003. http://www.who.int/csr/don/2003_09_10/en/ Last retrieval on 20th Sept 2003.

Lee N, Hui D, Wu A, et al. A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Hong Kong N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 1986–1994.

Epidemiology Program Office. Update: Outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome - Worldwide, 2003. Atlanta: Centres for Disease Control and Prevention 2003. MMWR 2003; 52: 241–248.

Ksiazek TG, Erdman D, Goldsmith CS et al. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 1953–1966.

Fouchier RA, Kuiken T, Schutten M et al. Aetiology: Koch's postulates fulfilled for SARS virus. Nature 2003; 423: 240.

Volk WA, Brown JC . Basic Microbiology. 8th ed. p 528. San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings, 1997.

Rota PA, Oberste MS, Monroe SS et al. Characterization of a Novel Coronavirus Associated with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. Science 2003 May 30; 300: 1394–1399.

Peiris JS, Lai ST, Poon LL, et al. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet 2003; 361: 1319–1325.

Seto WH, Tsang D, Yung RW et al. Effectiveness of precautions against droplets and contact in prevention of nosocomial transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Lancet 2003; 361: 1519–1520.

Holmes KV . SARS-associated coronavirus. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 1948–1951.

National Centre for Infectious Disease. Basic information about SARS. Atlanta: Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Aug 2003. http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/sars/factsheet.htmLastretrievalon18thSept2003.

Epidemiology Program Office. Preliminary Clinical Description of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. Atlanta: Centres for Disease Control and Prevention 2003. MMWR 2003; 52: 255–256.

Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre (CDSC). Fact sheet for clinicians: interpreting SARS test results. London: Health Protection Agency (HPA). Reviewed on 1st September 2003. http://www.hpa.org.uk/infections/topics_az/SARS/resultinterp.htm Last retrieval on 20th Sept 2003.

National Centre for Infectious Disease. Interim Domestic Infection Control Precautions for Aerosol-Generating Procedures on Patients with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). Atlanta: Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. May 2003. http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/sars/aerosolinfectioncontrol.htmLastretrievalon18thSept2003.

Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre (CDSC). Guidance on microbiological sampling and investigation of cases of SARS. London: Health Protection Agency (HPA). Reviewed on 1st September 2003. http://www.hpa.org.uk/infections/topics_az/SARS/micro.htm Last retrieval on 20th Sept 2003.

Department of Communicable Disease Surveillance and Responses (CSR). Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS): Laboratory Diagnostic Tests. Geneva: World Health Organization. April 2003. http://www.who.int/csr/sars/diagnostictests/en/Lastretrievalon18thSept2003.

Department of Communicable Disease Surveillance and Responses (CSR). Use of Laboratory Methods for SARS Diagnosis. Geneva: World Health Organisation. May 2003. http://www.who.int/csr/sars/labmethods/en/Lastretrievalon18thSept2003.

So LK, Lau AC, Yam LY, et al. Development of a standard treatment protocol for severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet 2003; 361: 1615–1617.

Department of Communicable Disease Surveillance and Responses (CSR). Preliminary Clinical Description of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. Geneva: World Health Organisation. March 2003 http://www.who.int/csr/sars/clinical/en/Lastretrievalon18thSept2003.

Department of Communicable Disease Surveillance and Responses (CSR). Update 49 - SARS case fatality ratio and incubation period. Geneva: World Health Organisation. 7th May 2003. http://www.who.int/csr/sars/archive/2003_05_07a/en/ Last retrieval on 18th Sept 2003.

Stohr KA . Multicentre collaboration to investigate the cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet 2003; 361: 1730–1733.

Epidemiology Program Office. Recommendations for prevention of HIV transmission in health-care settings. Atlanta: Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR 1987; 36: 1S–18S.

American Dental Association (ADA) Council on Scientific Affairs and ADA Council on Dental Practice. Infection control recommendations for the dental office and the dental laboratory. J Am Dent Assoc 1996; 127: 672–680.

Palenik CJ, Burke FJ, Miller CH . Strategies for dental clinic infection control. Dent Update 2000; 27: 7–10, 12, 14–15.

Scully C, Epstein J, Wiesenfeld D . Oxford Handbook of Dental Patient Care. pp 64–65, 85–88 Oxford: OUP, 1998.

Garner JS and the Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee, Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Guideline for Isolation Precautions in Hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1996; 17: 53–80, and Am J Infect Control 1996; 24: 24–52.

West KH, Cohen ML . Standard Precautions - A New Approach to Reducing Infection Transmission in the Hospital Setting. J Intraven Nurs 1997; 20: S7–S10.

Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre (CDSC). Guidance for hospital on the prevention of spread of SARS. London: Health Protection Agency (HPA). Reviewed on 25th July 2003. http://www.hpa.org.uk/infections/topics_az/SARS/hospguide.htm Last retrieval on 20th Sept 2003.

Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre (CDSC). Guidance for primary care practitioners on investigation, management and reporting of SARS cases and contacts (including community infection control). London: Health Protection Agency (HPA). Reviewed on 29th August 2003. http://www.hpa.org.uk/infections/topics_az/SARS/primarycare.htm Last retrieval on 20th Sept 2003.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, R., Leung, K., Sun, F. et al. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and the GDP. Part I: Epidemiology, virology, pathology and general health issues. Br Dent J 197, 77–80 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4811469

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4811469

This article is cited by

-

Emerging infections – implications for dental care

British Dental Journal (2016)