Key Points

-

The dental specialities can collaborate with the treatment of complex cases

-

Joint treatment planning is essential

-

A clear treatment plan must be agreed by all parties prior to treatment starting

-

Responsibility for each treatment stage must be agreed in advance

-

Combined treatment can produce high quality treatment outcomes in complex cases

Key Points

Orthodontics

-

1

Who needs orthodontics?

-

2

Patient assessment and examination I

-

3

Patient assessment and examination II

-

4

Treatment planning

-

5

Appliance choices

-

6

Risks in orthodontic treatment

-

7

Fact and fantasy in orthodontics

-

8

Extractions in orthodontics

-

9

Anchorage control and distal movement

-

10

Impacted teeth

-

11

Orthodontic tooth movement

-

12

Combined orthodontic treatment

Abstract

Dentistry is becoming more sophisticated and capable of providing much higher treatment standards than ever before. Treatments previously considered impossible can now be achieved as a direct consequence of these advances. However, this increased complexity of treatment also means that the different branches of dentistry have, as a necessity, become more and more specialised. It is important that the specialities collaborate in a systematic focused way to ensure the optimal treatment outcome with the minimum burden of care for the patient.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Recent advances in dentistry, coupled with patients' increased expectations and demands, means that some areas of clinical practice have become more specialised. An individual dentist is unlikely to have the necessary skills and expertise to undertake all aspects of treatment. In the management of complex cases joint planning between the orthodontist and the other dental specialities is important if a satisfactory treatment outcome is to be obtained. The dental specialities cannot work in isolation, and joint-working relationships should be fostered. Whilst orthodontists may be highly skilled in moving teeth, they are heavily dependent on other dental disciplines if optimal treatment outcomes are to be achieved in complex cases.

There are many areas in which orthodontic treatment may be of help to other dental specialities. Some of these are as follows:

-

Missing teeth

-

Traumatised teeth

-

Periodontal problems

-

Occlusal problems

-

Surgical problems

Missing teeth

The choice in these cases is usually to recreate space for the prosthetic replacement of missing teeth, or to close the space instead.

If an upper central incisor is missing then the usual choice is to open up the space and put in some form of prosthesis. If the space is closed and the lateral incisor is placed in the central incisor site, then camouflage is difficult because of the small width of the lateral that results in an unsightly emergence angle of the crown. In cases where an upper incisor is missing, the space may need to be re-distributed. The patient in Figure 1 had a partial upper denture, and it was difficult to restore the site with a bridge because of the inclination of the upper lateral incisor and the generalised spacing in the upper labial segment. Fixed appliances were therefore used to re-distribute the space in the upper arch. In order to maintain the appearance, a bracket was fitted to a denture tooth. At the completion of treatment the patient was fitted with an upper removable retainer carrying a denture tooth. Note the proximal metal stops on the upper right central and upper left lateral incisor, to prevent a space re-opening during retention. Finally a bonded bridge restored the site.

(c) A fixed appliance with a denture tooth to mask the space. (d) The space has been redistributed. (e) A retainer with a denture tooth. Note the proximal metal stops. If these are not used there is a risk of the teeth sliding past the denture tooth. (f) A bonded bridge was placed 1 year after the removal of the fixed appliance

When lateral incisors are missing the choice is not so clear-cut, and often depends on the amount of spacing the patient has, the buccal occlusion and the shape and colour of the canines. Opening the space for prosthetic replacement produces optimal aesthetics but has the disadvantage of the maintenance involved with this type of restorative treatment. Closing the space obviates the need for false teeth but this may produce a less satisfactory appearance.

Where there is considerable space, the buccal occlusion is well inter-cuspated and the canine has a pointed cusp tip then the usual treatment is to open the spaces. Closing spaces will affect the buccal occlusion, and if it is a well interdigitated Class I then this may not be the best option. The shape of the canines is important because if they are pointed they will look unsightly adjacent to the central incisor. Although the tips of the teeth can be trimmed to improve their appearance, this is not always the best choice. Figure 2 shows a case with spacing in the upper arch due to developmentally absent upper lateral incisors. The upper canines have very pointed tips and it would be difficult to modify the shape of these teeth to make them resemble lateral incisors. In addition, the buccal occlusion would make space closure very difficult. Therefore, space in the upper arch was recreated to allow prosthetic replacement. An upper fixed appliance with coil springs at the upper lateral incisor sites accomplished this task. At the completion of treatment, an upper retainer with denture teeth was used to restore the missing sites. This retainer was worn for a year prior to definitive restoration with adhesive bridgework.

If the canine teeth are more amenable to masking, and the buccal occlusion is not well inter-cuspated with less spacing in the upper arch, then consideration can be given to space closure. Figure 3 shows a case where this was accomplished, again using a fixed appliance and the tips of the canines subsequently trimmed. A good aesthetic appearance was achieved, but it is worth noting the slightly different colour of the canines in relation to the central incisors. If necessary, this can then be masked with veneers. Before the decision to open or close spaces is made, consultation with a restorative dentist or the patient's GDP is a pre-requisite.

Traumatised teeth

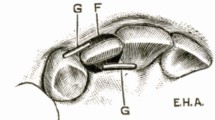

Traumatised, fractured, intruded or avulsed teeth may sometimes benefit from an orthodontic input. Teeth, which are fractured or intruded, may need extrusion, and this can be accomplished by using a number of different appliances and techniques. Figure 4 is an example of an upper appliance being used to extrude two unerupted upper incisors as an interceptive form of treatment. The upper permanent lateral incisors had already erupted; a clear sign that something was wrong. A supernumerary tooth, preventing the eruption of the central incisors, was first removed and brackets bonded to the central incisors. A modified palatal arch was then fitted and attached to the central incisor brackets with wire ligatures. The ligatures were gently activated to extrude the teeth. Once the teeth had erupted the remaining dentition was then allowed to develop prior to definitive orthodontic treatment. A similar technique can also be used to extrude fractured roots so that post-crowns can be placed on the teeth.

(b) The supernumerary was surgically removed and brackets bonded to the upper incisors. A modified trans-palatal bar with wire ligatures was used to extrude the teeth. (c) Once the teeth were successfully extruded the dentition was allowed to develop prior to comprehensive treatment in the permanent dentition

If upper incisors are traumatised and have a poor prognosis it is occasionally possible to transplant teeth to restore these sites. The main principles of transplantation have been well documented by Andreasen1 and provided these are followed, success rates in excess of 90% can be expected. Premolars are good teeth to replace upper central incisors because they often have the same width at the gingival margin as the teeth they are replacing. Figure 5 shows an example of a case where the upper incisors had a poor prognosis and were extracted. The lower first premolars were then transplanted into the extraction sites. Veneers were then placed on the premolars to produce a satisfactory treatment outcome. The advantage of transplantation over implants is that transplantation can be undertaken at an early age and will grow as the patient grows. If an implant were placed at this stage it would, as the child grows, become gradually submerged. There is also a risk of ridge resorption by waiting until the patient is old enough to have an implant placed. In addition the cost of transplantation is also considerably less than for implants.

(b) A peri-apical radiograph indicated that the teeth had a hopeless prognosis. (c) The teeth were extracted and two lower premolars transplanted into the extraction sites. The teeth were then aligned with fixed appliances. (d) At the completion of fixed appliance treatment veneers were placed on the transplanted teeth

Periodontal problems

With advanced periodontal disease, teeth are prone to drift producing an unsightly appearance. The teeth can be realigned orthodontically, but prior to this it is essential that all pre-existing periodontal disease is eliminated and the patient can maintain a meticulous standard of oral hygiene. If treatment is undertaken in the presence of active disease, very rapid bone loss can result.

Figure 6 shows a patient who had substantial vertical and horizontal bone loss, and as a consequence, drifting of the upper teeth had occurred, in particular the upper lateral incisor. Alignment of the teeth was achieved using fixed appliances. Near the completion of treatment a residual black triangle was left between the upper incisors. This is quite a common problem in adults and is caused by the inability of the gingival tissue to regenerate and re-form an inter-dental papilla. In order to reduce the size of the black triangle, some inter-proximal reduction was undertaken to reshape the mesial contact points of the incisors allowing the teeth to be brought more closely together. Permanent retention is needed in situations like this because the tooth will drift as soon as the appliances are removed.

She had extensive periodontal disease that needed addressing prior to any orthodontic treatment. (b) Fixed appliances were then used to realign the teeth. (c) A dark triangle between the anterior teeth is a common complication of treatment in adults. This is because the inter-dental papilla fails to regenerate. (d) Inter-proximal reduction (slenderizarition) of the contact points helped to substantially reduce the gap and improve the aesthetics

Occlusal problems

Orthodontics can be used to try and produce an optimal occlusion, and there are many situations in which this can be used.2 The occlusion can be adjusted to provide canine guidance, and eliminate non-working side interferences. In situations where anterior open bites exist, it is occasionally possible to close these down without the need to resort to surgery.3

Sometimes the occlusion can damage the teeth and supporting tissues. Figure 8 is an example of a patient with a unilateral cross bite extending from the upper central incisor to the terminal molar on the right hand side. This traumatic occlusion had produced substantial tooth wear. Treatment was carried out using an upper fixed appliance in conjunction with a quad helix to expand the upper arch, correct the cross-bite and align the teeth. At the completion of treatment the incisal tips were restored with composite.

Surgery

There is a limit to how much tooth movement can be achieved, and in cases with severe skeletal discrepancies, orthodontics alone is not capable of correcting the incisor relationship, or improving facial aesthetics. In these circumstances close liaison with an oral and maxillofacial surgeon will be required. An outline of the processes involved and the orthodontists role in orthognathic surgery has recently been reviewed.4

Figure 7 shows an example of a patient with a Class III skeletal pattern. There has been some dento-alveolar compensation with the lower incisors retroclined and the upper incisors proclined in an attempt to make incisal contact. There is no scope for correcting the incisor relationship further with orthodontics alone. A combined orthodontic/surgical protocol was established and the patient started treatment with fixed appliances, in order to decompensate the incisors. This made the incisor relationship and the facial profile worse. Clearly, patients need to be advised of this prior to the commencement of treatment. Once the incisors are decompensated and the arches co-ordinated the patient is ready for surgery. The maxilla was advanced 7 mm and the mandible set back by 6 mm, producing an overall change of 13 mm in the skeletal relationship. In addition, because the patient had a facial asymmetry, the mandible was rotated in order to correct this.

As dentistry becomes increasingly sophisticated with more treatment options available than ever before, no single specialty in dentistry can work alone to provide the full range of treatment options. Some of the most interesting aspects of orthodontic treatment come from working in a combined approach with one's colleagues and it is important to recognize and respect the skills of other disciplines. Work of this nature can be amongst the most satisfying both for the clinician and the patient.

References

Andreasen JO, Andreasen F . Textbook and color atlas of traumatic injuries to the teeth. 3rd ed. pp671–690. Munksgaard, Copenhagen: Mosby, 1994.

Davies SJ, Gray RMJ, Sandler PJ, O'Brien KDO . Orthodontics and occlusion. Br Dent J 2001; 191: 539–549.

Kim YH . Anterior openbite and its treatment with multiloop edgewise archwire. Angle Orthod 1987; 57: 290–321.

Sandy JR, Irvine GH, Leach A . Update on orthognathic surgery. Dent Update 2001; 28: 337–345.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Paul Cook for the use of figures 5(a-d)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Roberts-Harry, D., Sandy, J. Orthodontics. Part 12: Combined orthodontic treatment. Br Dent J 196, 449–455 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4811174

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4811174