Key Points

-

A high proportion of patients will not fully understand the consent to treatment even when adequate information has been provided.

-

Sufficient time should be given for patients to consider the disclosed information to allow them to understand the treatment procedure better.

-

Consent should be repeated before carrying out the actual treatment especially if some time has elapsed since signing the consent form and the actual time of treatment.

Abstract

Objective To determine whether parents of children attending the outpatient general anaesthesia (OPGA) session at the Eastman Dental Hospital, London fully understand the proposed treatment.

Design Observational study supported by structured questionnaires and interviews.

Setting Casualty service in the Department of Paediatric Dentistry and the Victor Goldman Unit (a day-stay general anaesthetic unit) of the Eastman Dental Hospital.

Main outcome measures The parents' understanding of the consent was assessed based on their knowledge of the actual treatment procedure, the type of anaesthesia to be used and the number and type of teeth that would be extracted.

Results Fifty-two of the 70 subjects (74%) approached completed both parts of the survey (interviews one and two). Results showed that 40% of the written consent obtained from the parents were not valid. The subjects' knowledge of the proposed treatment improved on the day of the actual treatment although 19% of them still did not fully understand the procedure. There was a statistically significant increase in the proportion of valid consent on the day of the actual treatment. Many of the subjects had no knowledge of the type of anaesthesia that would be used for their children but were more aware of the number and type of teeth that were going to be extracted. The time interval between the consent process and the actual treatment did not have any significant effect on the subjects' understanding of the consent, but it implied that with time the subjects' knowledge improved.

Conclusion A proportion of subjects did not fully understand the proposed treatment procedure even after being adequately informed. Appropriate measures should be taken to ensure that the patients or their guardians truly understand the proposed treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

It is common knowledge among dentists that no patient should receive dental treatment against his or her own will. The dentist's obligation to obtain the patient's consent to treatment is based on ethical principles, legal requirements and professional policies.1,2 Any treatment, investigation or examination performed without consent may result in legal action for damages and even criminal proceedings. The dentist may also be found guilty of serious professional misconduct by the healthcare professional's registration body.3,4,5 The increasing awareness amongst the population of their rights to autonomy have resulted in more formal complaints regarding dentists for treatment without consent.6

The consent process, although time consuming, provides an opportunity for the dentist to create a good patient-clinician relationship by communicating with the patient the details of the treatment and gearing the information to the specific needs and understanding of the patient. It also allows for the input of opinion and concern from the patient. This will build the patient's trust and confidence in the dentist if they feel fully informed and in control of their decisions about their treatment.

The General Dental Council has recently amended its definition of informed consent. Informed consent requires the dentist to explain to the patient the treatment proposed, the risks involved and alternative treatment. If a general anaesthetic or sedation is to be given, all procedures must be explained to the patient by the anaesthetist/sedationist. In this situation written consent must be obtained.7

There are two types of consent that may be given by the patient. Implied consent is assumed by reasonable inference from the patient's action even though there was no explicit consent given. It is when a patient seeks and approves proposed 'normal' dental treatment.8 Most treatment between a dentist and patient involves implied consent when for example, the patient opens the mouth for examination and allows a procedure to be done.9 However implied consent may not provide sufficient protection for the dentist against legal action.

Expressed consent is obtained from a patient for a specific procedure and should be obtained for any procedures that are not routine and that carry a material risk.9 Oral consent is one form of expressed consent and is normally adequate for routine treatment such as fillings and prophylaxis.10 It is valid and should be witnessed and properly documented in the patient's record. Written consent is the other form of expressed consent which is usually obtained for the more extensive treatment and essential where a general anaesthetic, relative analgesia or sedation is given.7,10 Though it is not absolutely necessary to defend a legal action by having written consent, it may provide proof that consent has been obtained.9 However, having written consent does not mean that the goals of informed consent have been met if insufficient information was disclosed or when the patient consented without fully understanding the procedure.11,12,12

In the United Kingdom, the legal age of consent for children for surgical, medical or dental procedure is 16 years or over.13 Children below this age would require the parent's proxy consent for treatment. Therefore the parents need to be properly informed of the procedure prior to consenting to the treatment.

The aim of this study was to determine whether parents of children attending the outpatient general anaesthesia (OPGA) session at the Eastman Dental Hospital, London fully understood the proposed treatment procedure and whether the written consent was valid.

Subjects and methods

This study involved a two-part survey of parents of children requiring multiple extractions under outpatient general anaesthesia (OPGA) at the Eastman Dental Hospital, London. The children were all under 16 years of age. They attended as self-referral or were referred from other sources, such as from general dental practitioners or the Community Dental Service.

These children were initially examined by the senior house officer (SHO) on casualty duty, where any necessary radiographs and investigations were carried out and the treatment plan formulated. The SHO then obtained the consent from the parents for the treatment to be provided under OPGA. The patients would then make another appointment for the extractions to be carried out in the Victor Goldman Unit, a day-stay general anaesthetic unit.

The casualty officers were given instructions by the author, to inform the parents verbally, in a standardised structured manner, the nature of the proposed treatment when obtaining the consent. They had to explain:

-

1

The type of anaesthesia that would be used during the extractions

-

2

The number of teeth that would be extracted

-

3

The type of teeth that would be extracted, whether they were primary or permanent teeth

They were also observed, whilst taking the consent, by one of the authors (MAMT) with a checklist to ensure that all necessary information had been passed to the parents. The parents were then asked to sign the consent form with all the above information recorded.

After consenting to their child's treatment, the parents were asked to participate in a short interview and to complete a questionnaire (interview one). The subjects were also informed of the second part of the survey that would be carried out on the day of the treatment. The escorts of the children, who may or may not be the parent who had signed the consent form, were approached to complete a similar interview and questionnaire on the day of the operation (interview two). In all but two cases, the subjects at interview two were the parents that had originally signed the consent form.

All the interviews were performed by the same author (MAMT). interview one was conducted in the Department of Paediatric Dentistry, during any of the casualty sessions that the author was able to attend. Interview two was conducted in the Victor Goldman Unit (VGU) where the OPGA sessions were held. The subjects were approached as soon as they arrived at the VGU, before their children were seen by the anaesthetic nurse who would then explain the entire procedure and begin the preparation for general anaesthesia. Each interview and completion of the questionnaire took between 1 to 5 minutes, the variation depending on the understanding of the question and fullness of the replies by the parents.

This study was conducted over a period of 6 months, from February to July 1998, after receiving the approval of the Ethics Committee of the Eastman Dental Hospital.

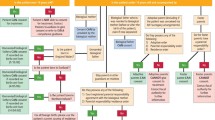

The particulars of the child and parents were recorded only during the first interview. The first three questions were conducted as a short interview for both parts of the survey. The remaining eight questions were left entirely for the parents to complete with minimum explanation and prompting where it appeared that the question was not fully understood (Fig. 1).

Data collected were entered into a computer using the Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Responses from the questionnaires were analysed using the SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) software for frequency distribution.

Results

Seventy subjects were approached for this study. Of these, 52 (74%) completed both parts of the survey (interviews one and two), 15 (22%) completed only one part of the survey (interview one) and 3 (4%) refused to participate in the study.

The results of this study were based on the responses of the 52 subjects who completed both parts of the survey. All the subjects claimed that they knew the treatment their children were going to have in response to the fourth question of the questionnaire.

At interview one, 69% (36) of the subjects knew the correct type of anaesthesia that their children would have ie general anaesthesia. The remaining 31% (16) of the subjects gave the wrong response by answering 'local anaesthesia', 'dental gas' or 'don't know' in the questionnaire. At interview two, 85% (44) of the subjects gave a correct response, whilst 15% (8) of the subjects still answered incorrectly to the question (Table 1).

The parents were also asked if their children were going to be asleep during the treatment. At interview one, 87% (45) of the subjects knew that their children were going to be asleep during the treatment while 13% (7) of the subjects either did not know or thought that their children would be awake. At interview two, all the subjects gave the correct response.

Most of the subjects (94%, 49) knew the correct number of teeth to be extracted at both interviews. One subject consistently did not know the correct number of teeth to be extracted on both occasions, two subjects did not know only at interview one and another two at interview two.

The subjects' had good knowledge of the type of teeth to be extracted. Only one subject did not know the type of teeth to be extracted at interview one. Knowledge of the treatment procedure was assessed by asking the parents if they knew whether their children were having dental extractions and/or dental fillings. At interview one, one subject did not know that the child was going to have dental extractions and six subjects thought that their children would have teeth restored at the same time. At interview two, one subject thought that the child would have restorations placed (Table 2).

The consent for treatment was considered not valid when there was at least one incorrect response in the questionnaire. At interview one, 40% (21) of the subjects gave consent for treatment that was not valid. This had decreased to 19% (10) at interview two (Table 3). The increase in the proportion of valid consent at interview two from interview one was statistically significant when the McNemar test was used (P = .001).

The overall validity of the consent was analysed according to the subjects' understanding of the English language. At interview one, 37% (17 of the 46) of the subjects who understood English did not give valid consent for the treatment of their children. This had decreased to 15% (7) at interview two.

Six (12%) subjects did not understand the English language. At interview one, four of the six subjects (67%) did not fully understand the consent that they had given for the treatment of their children, with one subject completing the questionnaire without using an interpreter. At interview two, three (50%) subjects did not give valid consent and two subjects completed the questionnaire without using an interpreter. The one subject who completed both interviews one and two without an interpreter did not give valid consent. Another subject who did not use an interpreter at interview two managed to answer the questionnaire correctly.

At interviews one and two, a higher percentage of subjects who did not understand English gave consent that was not valid. When Fisher's exact test was used the difference was not statistically significant when compared with subjects who understood English, on both occasions (P = 0.21 and P = 0.08 respectively).

At interview one, all the subjects who participated in the survey were the parents who signed the consent form. At interview two, two of the subjects were the escorts of their children on the day of treatment and had not signed the consent. They fully understood the proposed treatment procedure when assessed.

The mean time interval between the signing of the consent form and the day of treatment for a valid consent at interview two was 11.93 days (SD = 9.67) and that for consent that was not valid was 16.67 days (SD = 13.50). There were no significant effects of the time interval on the subjects' understanding of the consent when the mean time intervals were analysed using the independent samples t-test.

Discussion

This study showed that the subjects were more likely to understand the nature of the dental treatment than the type of anaesthesia to be used. They were more aware of the number and the type of teeth to be extracted because they probably believed that the dental extractions would cause a fairly significant 'degree of injury' to their children. They did not appear too concerned about the type of anaesthesia because they did not perceive it as a potential hazard to their children, which in reality could have much more risks attached.14

This study also found a statistically significant increase in the proportion of valid consent on the day of the actual treatment. There could be two possible reasons for the improvement in the subjects' understanding of the consent.

When recruiting the subjects for this study, they were informed of the second part of the survey to ensure their continued participation. This might have prepared them for the next interview and led to better retention of the information that was disclosed during the consent.

Another reason could be due to the reinforcement of the informed consent by the VGU staff carrying out the pre-anaesthetic assessment. Immediately after signing the consent and completing the first part of the survey, the subjects and their children were sent to the pre-anaesthetic clinic where a member of the VGU staff, either an anaesthetist or a nurse would examine the children and informed the parents of the whole treatment procedure again, especially regarding the general anaesthesia. Since the results showed that most of the initial errors in the responses in the questionnaire were regarding the type of anaesthesia, there was marked improvement of the parents' knowledge at interview two. This simple act of reinforcing the consent might have led the parents to be better informed of the treatment.

This study found no significant difference in the mean time interval of subjects who gave valid consent and those who did not at interview two. Since the overall validity of consent actually increased at interview two, it appeared that with time and having considered the matter further, the subjects' knowledge of the consent improved. The time interval between the consent process and the actual treatment is fairly important. On the one hand, sufficient time should be given for the patients, or their guardians to consider the disclosed information,9 but too long an interval might cause them to be unable to recall the information15 making the consent invalid.

The most outstanding finding of this study was the fact that 40% of the consent obtained for treatment was not valid immediately after the consent form was signed. The parents simply did not fully understand the consent even after adequately being informed of the actual treatment and the type of anaesthesia for their children. The situation improved on the actual day of treatment although 19% of the subjects still did not fully understand the consent on that day.

The signing of the consent form is of secondary importance although it may provide evidence that informed consent has been obtained. The clinician may still be liable to a charge of negligence if it can be proven that the patients or their guardians have not been adequately informed of the treatment procedure. Furthermore, as clinicians it is our moral responsibility to ensure that the patients or their guardians realise the exact treatment procedure that will be carried out before we commence treatment.

There are several methods to improve informed consent that will hopefully ensure that all consent to treatment is valid. One suggestion is the use of written information sheets that will allow the patients to digest the information on the treatment procedure at their own pace and check on certain information that they have forgotten at any time. There should still be a verbal discussion of the consent with the clinician, which will also provide the opportunity for the patients to clarify any doubts that have not been addressed in the information sheets.

Informed consent videotapes and Digital Versatile Disks (DVD) should also be considered as an effective method in giving standardized information for routine procedures such as dental extractions and type of anaesthesia. The use of such audio-visual aids may complement verbal informed consent that can be of variable quality.

Only after the patients have had sufficient time to understand all the information should they be asked if they are prepared to sign the consent form. This will likely be at the second visit. It seems unfair to ask patients to sign an informed consent form at the first visit when they have not had time to digest the information disclosed nor read information sheets or obtain other information about the treatment. Consent should also be repeated before carrying out the actual treatment procedure, especially if some time has elapsed between the signing of the consent form and the actual time of treatment.

It is also necessary to have reliable interpreters when communicating with patients or their guardians who do not understand the English language. The ideal interpreter is another clinician who can explain the exact treatment procedure in the patient's language. A member of auxiliary staff may be equally useful. It is important for the clinician to be aware of the interpreter's ability to communicate the exact information disclosed to the patients or their guardians. Therefore, it is recommended that professional interpreters employed by the health authorities be used to communicate with non-English speakers rather than friends or relatives of the patients. This will ensure the quality of interpretation and information given to the patients and that if there is any disagreement on the information disclosed, it is more likely to be able to rely on the account of the impartial interpreter.

Conclusion

The importance of consent to treatment cannot be over-emphasised. Even when seemingly adequate information on treatment was provided, a high proportion of the subjects did not fully understand the proposed treatment procedure. Appropriate measures must be taken to ensure that the patients or their guardians are truly informed of the treatment procedure.

References

Rozovsky LE . Imposing your will upon the patient. The temptation can have legal consequences. Oral Health 1986; 76: 51–53.

Etchells E, Sharpe G, Walsh P, Williams JR, Singer PA . Bioethics for clinicians: 1. Consent. Can Med Assoc J 1996; 155: 177–180.

Bailey BL . Informed consent in dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc 1985; 110: 709–713.

St Clair T . Informed consent in pediatric dentistry. A comprehensive overview. Pediatr Dent 1995; 17: 90–97.

Mitchell J . A fundamental problem of consent. Br Med J 1995; 310: 43–48.

Doyal L, Cannell H . Informed consent and the practice of good dentistry. Br Dent J 1995; 178: 454–460.

Maintaining Standards. Guidance to dentists on professional and personal conduct 1997 Amended 1999 London: General Dental Council; Consent 3.7.

Hagan PP, Hagan JP, Fields HW, Machen JB . The legal status of informed consent for behaviour management techniques in pediatric dentistry. Pediatr Dent 1984; 6: 204–208.

Consent to Treatment revised by J Gilberthorpe London; Medical Defence Union 1996 p 5.

Advice Sheet B1. Ethics in Dentistry London; British Dental Association 1995: 49–53.

Cassileth BR, Zupkis RV, Sutton-Smith K, March V . Informed consent – Why are its goals imperfectly realized? N Engl J Med 1980; 302: 896–900.

Waisel DB, Truog RD . Informed Consent. Anesthesiol 1997; 87: 968–978.

Family Law Reform Act (1969) Section 8(1). The Public General Acts and Church Assembly Measures 1969; Part I. Chapter 46: 997–1021 London: HMSO.

Worthington LM, Flynn PJ, Strunin L . Death in the dental chair: an avoidable catastrophe? (Editorial). Br J Anaesth 1998; 80: 131–132.

Lavelle-Jones C, Byrne DJ, Rice P, Cuschieri A . Factors affecting quality of informed consent. Br Med J 1993; 306: 8859–8890.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mohamed Tahir, M., Mason, C. & Hind, V. Informed consent: optimism versus reality. Br Dent J 193, 221–224 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4801529

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4801529

This article is cited by

-

Ambulante zahnärztliche Behandlung von Kindern und Jugendlichen in Allgemeinanästhesie

Oralprophylaxe & Kinderzahnheilkunde (2022)

-

Exploring how newly qualified dentists perceive certain legal and ethical issues in view of the GDC standards

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

Mothers’ perceptions of their child’s enrollment in a randomized clinical trial: Poor understanding, vulnerability and contradictory feelings

BMC Medical Ethics (2013)

-

An audit of the level of knowledge and understanding of informed consent amongst consultant orthodontists in England, Wales and Northern Ireland

British Dental Journal (2008)

-

How informed is informed consent?

British Dental Journal (2002)