Key Points

-

Physiognomy is the judging of an individual's character from their facial appearance. This practice exists in many cultural groups and notably among Chinese groups.

-

There are a number of aspects about teeth that are used in physiognomy. This study explored whether young Chinese adults in Hong Kong 'heard about' and 'believed in' dental aspects of physiognomy.

-

This paper raises an awareness of traditional health beliefs and ideologies that are of interest to all those delivering care in multicultural environments.

Abstract

Objectives To determine knowledge and beliefs about traditional physiognomy (judging an individual's character from their facial appearance) concerning teeth among young (17–26) and middle-aged (35–44) Hong Kong adults.

Methods In a cross sectional ethnographical telephone survey, 400 adults were interviewed about 16 traditional physiognomy concerning teeth (in consultation with a Feng Shui specialist).

Results Most completed the interview (93%, 373). Over half the study group (63%, 234) claimed they had heard of aspects of physiognomy concerning teeth, and a quarter (24%, 88) believed in such ideologies. Variations in knowledge and beliefs were apparent among people of different age (P<0.01), gender (P<0.05), educational attainment (P<0.01), economic status (P<0.01), place of birth (P<0.01) and religion (P<0.01). Their knowledge and belief in aspects of physiognomy concerning teeth was also associated with reported use of dental services (P<0.01).

Conclusion Among young and middle-aged adults in Hong Kong, knowledge and beliefs concerning traditional physiognomy regarding teeth is strong, and socio-demographic variations exist in these perceptions. These findings have implications for all those involved in the delivery of dental care in multicultural societies and in raising cultural awareness about traditional health beliefs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Despite the importance attributed to ethnography in general health; relatively few studies have explored cultural dental health beliefs.1 Cultural health beliefs can affect attitudes towards oral health,2 oral health behaviour practices and habits,3,4 including service utilisation.5,6 In some cases, such health beliefs may even result in tooth mutilation or tooth defacement practices among certain indigenous groups.7,8 Moreover, raising cultural awareness relating to oral health among dental professionals is important in the production of oral health education material,9 in targeted approaches to promoting oral health and delivering care in multicultural societies.10

Physiognomy is the study of the assumed ability to judge the physical, mental or moral character of an individual by the qualities of their face.11 This art of reading personality traits from faces dates back to ancient times and is still very popular among many ethnic groups, particularly among ethnic Chinese communities.12 Chinese physiognomy is based on numerous fortune-telling theories such as Ying-Yang, Five Elements and Pa Kua, and religious ideologies including Taoism and Buddhism.13 There is a common consensus among historians that physiognomy has played an important role in cultural development and that social behaviour in many Chinese societies is still strongly affected by these traditional beliefs.14

There is a lack of information about the dental aspects of physiognomy, which has implications in understating oral health beliefs and behaviour, and the delivery of oral healthcare in multicultural societies.

AIMS

This study aimed to investigate the context of traditional beliefs in Chinese physiognomy in the Hong Kong SAR, China. To determine how prevalent knowledge about these ideologies are, and the attitudes of young (17–26) and middle-age (35–44) adults in Hong Kong towards these beliefs. In addition, this study attempted to distinguish socio-demographic variations in perceptions about traditional physiognomy concerning teeth, and to identify their association with reported use of dental services.

Methodology

Questionnaire design

Following a review of the literature on Chinese physiognomy and health, a search of local Feng Shui publications (in Chinese) held by the Hong Kong Urban Council, and an in-depth consultation with a practising Feng Shui specialist, a sixteen-item questionnaire was developed to assess dental aspects of Chinese physiognomy. This included items relating to size, position, colour, tooth restorations and number of teeth. The questionnaire was piloted among a group of dental patients for face and content validity.

Data collection

The vehicle for this study was a cross sectional telephone survey conducted with the assistance of Social Science Research Centre (SSRC), University of Hong Kong. The sample frame was a random sample of Hong Kong telephone numbers provided by the SSRC. Over 97% of households in Hong Kong have access to a telephone.15 When telephone contact was established, inclusion criteria were assessed; participants had to be Hong Kong residents, Chinese speaking, and young (17–26) or middle-aged (35–44). A sample size of 400 adults was considered appropriate to provide a confidence interval of +/- 4% with an estimated prevalence that 20% of the population believed in aspects of Chinese physiognomy.13

Data analysis

Data was coded and analysed using the statistical package SPSS. Frequency tables were produced to identify aspects of Chinese physiognomy frequently heard about and believed in Hong Kong. The characteristics of the groups were examined for similarity and were of comparable makeup by age and gender. Socio-demographic (age, gender, education, economic status – based on housing type, ethnicity – place of birth, and religion) variations in the number of aspects that they had heard about and believed in were explored employing t-test statistics. Analyses were conducted on log transformed (ln) data because the data was not normally distributed. The results presented are based on the exponential of log (ln) transformed values.

Results

Most completed the interview in full (93%, 372) and a minority declined to participate most frequently because of time constraints. The profile of the study group is presented in Table 1.

The majority (63%, 234) had heard of some aspects of traditional physiognomy concerning teeth. Most frequently having heard that 'missing incisors causes loss of wealth' (44%, 164) and that 'teeth in older people spoils the luck and fortune of their descendents' (32%, 118). Very few (1%, 5) had heard that 'people with spaces between their teeth have a short life span' or that 'short teeth are a sign of a stupid person' Table 2.

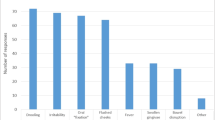

Knowledge about traditional physiognomy concerning teeth was associated with age (P=0.001), gender (P=0.03), educational attainment (P=0.001), place of birth (P<0.001), religion (P<0.001) and type of house lived in (a proxy measure of economic status) (P<0.001), Figure 1.

Twenty-four per cent (88) claimed they 'believed' or 'deeply believed' in one of the sixteen aspects of traditional physiognomy concerning teeth. Most frequently believing that 'missing incisors causes loss of wealth' or that 'people with 'extra' teeth have good fortune and wealth', Table 1.

Belief in aspects of traditional physiognomy concerning teeth was associated with age (P=0.002), gender (P=0.02), educational attainment (P=0.002), place of birth (P<0.001), religion (P<0.001) and type of housing (a proxy measure of economic status) (P=0.002), Figure 2.

Very few (5) claimed that they actually consulted a dentist because of aspects relating to physiognomy. These people were more likely to have heard about (P=0.004) and believed in (P<0.001) a greater number of dental aspects of physiognomy compared with others in the study group, Table 3.

Discussion

Interestingly, a review of the literature on traditional physiognomy, local Feng Shui publications, and an in-depth consultation with a practicing Feng Shui specialist revealed many aspects about teeth important to traditional physiognomy: number, size, shape, colour and even type of dental restoration. This provides an insight into the salience of teeth even in ancient times and its considered importance in overall facial appearance. Moreover, it draws attention to the fact that assumptions are made about people from their facial appearance and this too is reported to be a common practice in the West.12

Over half of the study groups claimed they had heard of aspects of physiognomy relating to teeth and approximately a quarter 'believed' or 'strongly believed' in aspects of the ideology. This supports earlier findings that suggest that the prevalence of traditional health beliefs is widespread among Chinese people. In Hong Kong, for example, many hold the belief that 'hot air causes gum disease' and use 'cooling teas to treat toothache, gum disease and other oral health problems'.16

Middle-aged people were more likely to have heard of and believed in dental aspects of physiognomy compared with younger adults. This may be attributed to a cohort effect and the influence of modernization. Hong Kong, a former British colony has undergone major modernization over the past few decades and its culture is perceived by many as a hybrid of Eastern and Western values.13 Modernization is a multifaceted phenomenon with pervasive influences socio-culturally on belief and value systems.14

Women had greater knowledge about aspects of traditional physiognomy and were more likely to believe in it than men. This in part may reflect the role of women in many societies as primary caregivers in the family with responsibilities for health and health behaviour.17 However, it too may reflect women's willingness to express their views about their health beliefs compared with men's unwillingness as has been suggested.18

People of lower educational attainment and poorer economic background (based on housing) were more likely to have knowledge of and believed in traditional physiognomy. This is an important association to consider in the targeting of oral health promotion strategies in the population.

People born in Mainland China more frequently had heard and believed in physiognomy compared with those born in Hong Kong. This draws attention to the variations in traditional health beliefs that exist among what is often considered as a homogenous ethnic group (Chinese). Greater understanding of the diversity that exist among ethnic groups may facilitate planning and the delivery of oral health care services.3,5

Interesting too, is the association between religious beliefs and traditional health beliefs. The influence of religious belief is increasingly emerging as an important predictor of oral health behaviour and oral health.19,20 This is a research area not well understood.

Very few people claimed to have attended a dentist because of aspects relating to physiognomy. Among them, they were more likely to have heard about and believed in a greater number of dental aspects of physiognomy. This draws attention to association between traditional health beliefs and oral health behavior that may be important among a minority of ethnic groups.

The study concludes that knowledge about and belief in ideologies surrounding dental aspects of traditional physiognomy is widespread among young and middle-aged adults in Hong Kong. This highlights the prevalence of traditional health beliefs and sets to raise cultural awareness among dental professionals about these ideologies which may be relevant to professional practice and patient health behaviours, especially in multicultural societies.

References

Nettleton S Understanding dental health beliefs: an introduction to ethnography. Br Dent J 1986; 161: 145–147.

Strauss RP Culture, dental professionals and oral health values in multicultural societies: measuring cultural factors in geriatric oral health research and education. Gerodontology 1996; 13: 82–89.

Vora AR, Yeoman CM, Hayter JP Alcohol, tobacco and paan use and understanding of oral cancer risk among Asian males in Leicester. Br Dent J 2000; 188: 444–451.

Watt RG A national survey of infant feeding in Asian families: summary of findings relevant to oral health. Br Dent J 2000; 188: 16–20.

Kwan SY, Williams SA Attitudes of Chinese people toward obtaining dental care in the UK. Br Dent J 1998; 185: 188–191.

Pearson N, Croucher R, Marcenes W, O'Farrell M Dental service use and the implications for oral cancer screening in a sample of Bangladeshi adult medical care users living in Tower Hamlets, UK. Br Dent J 1999; 186: 517–521.

Jones A Tooth mutilation in Angola. Br Dent J 1992; 173: 177–179.

Fitton JS A tooth ablation custom occurring in the Maldives. Br Dent J 1993; 175: 299–300.

Lowe PA, Bedi R An evaluation of practice leaflets provided by general dental practitioners working in multi-racial areas. Br Dent J 1997; 182: 64–68.

Gelbier S, Taylor SG Some Asian communities in the UK and their culture. Br Dent J 1985; 158: 416–418.

Clayton LT Taber's Cyclopedic Medical Dictionary. China: Oxford University Press 1993.

Hassin R, Trope Y Facing faces: studies on the cognitive aspects of physiognomy. J Pers Soc Psychol 2000; 78: 837–852.

Bond MH Beyond the Chinese Face. China: Oxford University Press 1991.

Gauld RD A survey of the Hong Kong health sector: past, present and future. Soc Sci Med 1998; 47: 927–939.

Hong Kong SAR Census and Statistics: Survey of Communication networks Hong Kong: Hong Kong Government Information Bureau 2001.

Lim LP, Schwarz E, Lo EC Chinese health beliefs and oral health practices among the middle-aged and the elderly in Hong Kong. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1994; 22: 364–368.

Seward MH Women's health promotion. J Dent Educ 1999; 63: 231–237.

Watson MR, Gibson G, Guo I Women's oral health awareness and care-seeking characteristics. J Am Dent Assoc 1998; 129: 1708–1716.

Bedi R Ethnic indicators of dental health for young Asian schoolchildren resident in areas of multiple deprivation. Br Dent J 1989; 166: 331–334.

Godson JH, Williams SA Oral health and health related behaviours among three-year-old children born to first and second generation Pakistani mothers in Bradford, UK. Community Dent Health 1996; 13: 27–33.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Drs K. L. Chan, K. M. Cheung, C. W. Lam, K. K. Lee, C. S. Ng, S. T. Ng, C. Y. Seh and Y. L. Yiu for their assistance with this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McGrath, C., Liu, K. & Lam, C. Physiognomy and teeth: An ethnographic study among young and middle-aged Hong Kong adults. Br Dent J 192, 522–525 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4801417

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4801417

This article is cited by

-

Ideals of Facial Beauty Amongst the Chinese Population: Results from a Large National Survey

Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (2020)

-

Ideals of Facial Beauty Amongst the Chinese Population: Results from a Large National Survey

Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (2018)

-

Anterior dental aesthetics: Facial perspective

British Dental Journal (2005)