Key Points

-

Access to specialist restorative dental care is affected by remoteness from urban centres and is a particular problem in the Island regions of the country.

-

Most dentists in urban areas said they felt that they had good access to a secondary referral service whereas most of those in rural areas either said they had no access to such a service or that access was difficult.

-

The most commonly referred conditions in the opinion of general dental practitioners were assessment and treatment planning for tooth wear and referral for apicectomy.

Abstract

Objectives: To compare the reported level of use of secondary care services for restorative dental care in rural and urban areas of Scotland.

Design: Postal questionnaire survey

Subjects and Methods: Postal questionnaire sent to all dentists in the Highland region, the island regions in Scotland and Dumfries & Galloway (n = 150) and an equal number were sampled from the remainder of Scotland stratified by health board area. Non-respondents were sent 2 reminders after which 62% of the sample had responded.

Results: Most dentists (85%) who practised in what they considered were urban areas of Scotland said they felt that they had good access to a secondary referral service. Whereas most of those who practised in what they considered were rural areas either said they had no access to such a service (26%) or that access was difficult (53%), only 3% of those in urban areas said they had no access to a secondary restorative consultative service compared with14% of dentists practising in rural areas of mainland Scotland and 54% of those practising on Scottish islands.

Conclusions: The survey suggests the people of the Scottish islands and some of the remoter parts of the Scottish mainland would be among those who might benefit from improvement in access to a restorative dentistry consultant service.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Restorative dentistry has been recognised as a specialty in the UK since 1973. Its growth as a specialty is considered to stem from the development of more complex 'high technology' forms of treatment; the need for comprehensive periodontal assessment and for advice and treatment of periodontal problems and the presentation of greater number of patients exhibiting tooth wear.1

The literature on restorative dental referrals is relatively sparse.2 Earlier studies have considered the demographic factors and treatment needs of patients attending a particular receiving centre.3,4,5 Latterly concern has moved towards issues concerned with general dental practitioners' referral practise6,7,8,910,11 and their opinions of their secondary referral service.2

A concern in the NHS at present is the need to provide better, fairer access to services.12 An issue in this should be the care of patients in remote and island areas. The Thomson report recommended that specialists in dental care should visit single handed practices in the remote and island areas of Scotland.13 This was not only to provide secondary care for patients but also as a means of imparting knowledge about new dental techniques. However, the system currently in operation for restorative dentistry consists of six-monthly visits to Orkney only. The Thomson report also acknowledges that the use of video consultations in medicine is a developing technique and may help to redress the access problems of remote and rural areas in the long term.

Various definitions of what is remote or rural exist. In Scotland, for land reform legislation, the term rural refers to any part of Scotland which is not a settlement.14 The islands of Orkney and Shetland have 54% or less of their population living in settlements, and the Scottish mainland regions of Dumfries & Galloway and Highland have fewer than 70% in settlements.14 The Remote and Rural Areas Resource Initiative (RARARI) considers that remoteness implies healthcare on islands or single or double-handed professional practise, at some distance from hospital or educational facilities. Whereas rurality implies the extra costs of providing a core NHS service in a location some distance from bigger distance general hospitals. A pragmatic approach to defining a rural area is to ask people how they view their own location. When general dental practitioners were asked, 10% described their dental practice catchment area as being rural using their own opinion about what this entails. The highest incidence of 'rural' dental practise was in Wales where 16% of dentists describe their practices as such.15 However, Scotland contains perhaps the most remote (if not the most rural) areas in the United Kingdom in the islands that make up the Orkneys, the Shetlands and the Western Isles. This is significant because it may be remoteness from a centre, rather than being rural that has the more pertinent effect on decisions about whether to refer for secondary care. Studies have shown that even comparatively small distances (eg 20 miles) from a referral centre can be a significant barrier to seeking advice from a dental consultant.7,10

The potential need for a dental restorative consultant service may be on the increase as more of the Scottish population retain some of their own teeth than in the early 1970s. The proportion of the Scottish population who have retained some of their natural teeth in 1998 (72%) has markedly increased since 1972 (56%). Furthermore, 1% of the Scottish population has what can be described as severe toothwear.16 The last inclusion of the islands of Scotland in a national dental survey of adults was in 1972.17 The survey concluded that the Highlands and Islands had problems of access to primary care in comparison with the remainder of Scotland, but the authors were not convinced that this manifested itself in terms of specific aspects of oral health such as total tooth loss. They were not significantly different to that of age-matched adults in the rest of Scotland.

This study has been undertaken to determine whether dentists currently working in remote or rural areas believe they have problems of access to secondary care in order to assess whether alternative means of providing such a service might be worth consideration.

The Highlands & Islands Teledentistry (HIT) Project is a consortium, led by Martyn Steed, General Dental Practitioner & Scottish Council for Postgraduate Medical & Dental Education, consisting of Martin Donachie, Grampian Universities Hospital Trust; Nigel Nuttall, Dundee University; Moya Nelson, Orkney Health Board; Tracy Ibbotson, Glasgow University; William Longstaff, General Dental Practitioner; Keith Duguid, Aberdeen University; Paul Scuffham and John Posnett, University of York. The HIT project is supported by grants from the NHS R&D Programme in Primary Dental Care and the Scottish Council for Postgraduate Medical and Dental Education. Nigel Nuttall acknowledges funding by the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Executive Department of Health who do not necessarily share the views expressed in this paper.

Method

The data was collected as background for the Highlands and Islands Teledentistry Project. A questionnaire was developed to determine the referral practise of dentists and their views about the potential for teledentistry as a means of facilitating secondary care. This paper considers their referral practise. In order to obtain a sufficient number of responses from dentists in predominantly rural areas, all dentists in the Highland region, the island regions (Orkney Islands, Shetland Islands and Western Isles) and Dumfries & Galloway were identified (n = 150). This definition of areas that can be considered as rural in Scotland mirrors that of the Remote and Rural Areas Resource Initiative (RARARI) with the exclusion of Argyll & Bute from the list of rural areas in the present study. The same number (n = 150) were randomly selected from lists of dentists practising in each of the health board areas of the remainder of Scotland. The number selected from each health board area was in direct proportion to the total number of dentists practising in each area in order to get a reasonable cross-section from the remainder of Scotland. Figure 1 is a map of Scotland showing these areas.

Two reminders were sent to non-respondents. For the purpose of this paper the dentists' own assessment of their practice catchment area, determined by the questionnaire, was used to examine differences between urban, mixed and rural areas.

Results

After two reminders were sent to non-respondents the overall response rate was 62%. There was a better response to the questionnaire from the rural regions (69%) than from the remainder of Scotland (55%). The dentists were asked to describe the catchment area of their practice (Table 1). This broadly confirmed the initial subdivision of Scotland into areas that were more rural than urban. Eighty-six per cent of those who said their practice catchment area was rural or predominantly rural were from the 'rural' regions selected; whilst 76% of those described their practice as urban or predominantly urban were from the remainder of Scotland. The dentists' own descriptions of their practice area are used in preference to the regional subdivision of Scotland from here on.

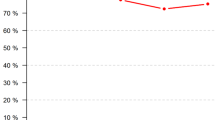

The dentists were asked to estimate how many patients they referred for secondary restorative consultations in an average year (Fig. 2 For most dentists (73%) the referral rate for restorative care was described as less than one person per month. Nevertheless there was a marked difference between the self-reported referral rates of dentists in urban areas and those in rural or mixed areas. There was no statistically significant difference between the referral rates of those in mixed and those in rural areas, but there was a marked difference between both of these groups and those in urban areas (P < 0.01). A third (34%) of those in rural areas and 28% of those in mixed areas said they would not refer any patients for restorative care in an average year compared with 7% of those in urban areas.

Table 2 shows the dentists' estimate of the distance to a referral centre for dental restorative care from their dental practice. There were significant differences between the practices in urban, mixed and rural areas in terms of estimated distance to the centre. Overall rural practices were judged to be about four times further away from their most appropriate referral centre than practices in urban areas. Perceived distance was also related to whether a dentist said they used a referral service. Dentists practising in mixed or rural areas who said they would not expect to refer any patients for secondary consultation in an average year reported being further away from a referral centre than those in a similar type of area who said they would expect to refer some patients.

Figure 3 illustrates that most dentists in urban areas (85%) said they felt that they had good access to a secondary referral service whereas most of those in rural areas either said they had no access to such a service (26%) or that access was difficult (53%). Only 3% of those in urban areas said they had no access to a secondary restorative consultative service. Those in mixed areas were fairly evenly split between those who said they had good access (48%) and those who felt access was difficult (34%) or non-existent (17%). The issue of having 'no access' to a restorative consultant was examined further among the rural group by dividing them into dentists practising on the Scottish mainland (N = 29) and those on a Scottish island (N = 13). Most of the dentists practising on Scottish islands, who responded to the question, said they had 'no access' to a secondary restorative consultative service (54%) compared with 14% of those in rural areas of mainland Scotland (P > 0.01).

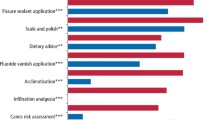

The respondents were asked how commonly they would refer conditions from a specified list for secondary restorative consultation. There were no statistically significant differences between dentists working in different areas in terms of what they said they would commonly refer and what they would rarely refer. Figure 4 The most commonly referred conditions were: treatment planning for tooth wear (45.8% said this was a common reason for referral); referral for apicectomy (41.8%) and assessing tooth wear (35.3%). The most rarely referred conditions were assessing teeth for suitability for endodontic treatment (80.5% said this was a rare reason for referral) and design of partial dentures (79.4%).

Discussion

The overall response rate (62%) to the survey is at the low end of that defined as acceptable for the purpose of publication in the British Dental Journal.18 However, the level of response is equal to the average achieved for postal questionnaires of general dental practitioners across 42 published reports surveyed by Tan and Burke.19 Non-response was greater among dentists working in the non-rural areas of Scotland (55%) than those in rural areas (69%). A factor in this may have been the labelling of the questionnaire with the project title: Highlands and Islands Teledentistry Project. Although a covering letter explained that we needed information from the whole of Scotland for comparative purposes some of those in the non-rural regions may have decided not to respond, as they were not in the Highlands and Islands. This type of non-response is perhaps less troublesome in terms of the bias it is likely to introduce than non-response due directly to the subject matter contained in the questionnaire.

A second methodological issue concerns the counting of dentists from the same practice. This affects the rural group mostly, as all dentists in the 'rural' regions of Scotland were contacted. The approach taken was to allow multiple responses from the same practice on the basis that dentists would probably be the better 'unit of measurement' in this study. The rationale underlying this was that individual dentists are a better proxy measure for the number of patients affected than individual practices, as practices can vary much more in terms the number of patients served. The dentists were asked to give their own estimates of number of patients referred and mileage to a secondary referral centre. Whilst this might not yield entirely factually correct data estimated distance may actually be more useful as an indicator of the 'impact' of location on a dentist's referral practise as it is likely that they will be an indication of the dentist's impression of remoteness.

The most commonly referred conditions in the opinion of general dental practitioners were: assessment and treatment planning for tooth wear and referral for apicectomy, followed by issues involved in the management of periodontal disease. This is largely in agreement with the view from the consultant side of the fence that has identified periodontal treatment planning and issues concerning tooth wear as issues which frequently arise in cases referred from primary dental care.1

This survey has confirmed the view that dental practices in rural areas do not have equality of access to secondary referral services. Only a fifth of dentists working in the rural areas of Scotland described their access to secondary referral services as 'good'; whereas a quarter said they had no access to such a service. Perceived distance was a factor contributing to the view that there was 'no access' to a restorative consultant service, an additional pertinent barrier appeared to be the sea; over half of the dentists on the Scottish islands said they considered themselves to have no consultant service for restorative dental care. Linden has also shown that referral for periodontal services are much greater from dentists within 25 miles of Belfast than those further away.7 Similarly, in Leeds a distance in excess of 20 miles would have dissuaded many dentists for referring an elderly patient for restorative care.10 In Scotland the distances concerned are much greater than these; rural practitioners reported themselves as being, on average, over 100 miles away from their nearest secondary referral centre. It is therefore unsurprising that rural dentists were much more likely to say they did not refer patients for secondary restorative care (34%) than their colleagues in urban areas (7%).

Conclusions

Better and fairer access to care is a key concern in the NHS in Scotland at the present time.12 This study has confirmed the view that, in the opinion of the dentists who responded to the questionnaire, remote areas of the Scottish isles are not as well served by secondary restorative dental services as urban areas.

References

Ralph JP Consultant services in restorative dentistry. Br Dent J 1995; 179: 188–189.

Fairbrother KJ Nohl FS A Perceptions of general dental practitioners of a local secondary care service in restorative dentistry. Br Dent J 2000; 188: 99–102.

Yemm R Analysis of patients referred over a period of five years to a teaching hospital consultant service in dental prosthetics. Br Dent J 1985; 159: 304–306.

Basker RM Harrison A Ralph JP A survey of patients referred to restorative dentistry clinics. Br Dent J 1988; 164: 105–108.

Callis PD Charlton G Clyde JS A survey of patients seen in consultant clinics in conservative dentistry at Edinburgh Dental Hospital in 1990. Br Dent J 1993; 174: 106–110.

O'Brien K McComb J L Fox N Bearn D Wright J Do dentists refer orthodontic patients inappropriately? Br Dent J 1996; 181: 132–136.

Basker RM Harrison A Ralph JF Patterns of referral to restorative dentistry clinics (abstract). J Dent Res 1987; 66: 849.

Linden GJ Variation in periodontal referral by general dental practitioners. J Clin Periodontal 1998; 25: 655–661.

McAndrew R Potts AJ McAndrew M Adams S Opinions of dental consultants on the standard of referral letters in dentistry. Br Dent J 1997; 182: 22–25.

Coulthard P Kazakou I Koron R Worthington HV Referral patterns and the referral system for oral surgery care. Part 1: General Dental Practitioner referral patterns. Br Dent J 2000; 188: 142–145.

Jardine SJ Basker RM Ralph JP Problems in restorative dentistry: who copes with them? Br Dent J 1995; 178: 176–179.

Our National Health: A plan for action, a plan for change Edinburgh: Scottish Executive Publications 2000.

Thomson TJ Health Care Services in Remote and Island areas in Scotland Edinburgh; HMSO 1995.

Thomas F Scottish Settlements – Urban and Rural Areas in Scotland Edinburgh: General Register Office for Scotland 2001.

Kitchen S Ashworth J Final Report. Survey of GDP's workloads London: BMRB Social Research 2000 p20.

Kelly M Steele J Nuttall N Bradnock G Morris J Nunn J Pine C Pitts N Treasure E White D Adult Dental Health Survey - Oral Health in the United Kingdom 1998 London: The Stationery Office 2000; pp98: 418–425.

Todd JE Whitworth A Adult Dental Health in Scotland 1972 London: HMSO 1974.

British Dental Journal Guidelines for acceptable response rates in epidemiological surveys in the BDJ. Br Dent J 2000; 189: 560.

Tan RT Burke FJ T Response rates to questionnaires mailed to dentists. Int Dent J 1997; 47: 349–354.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nuttall, N., Steed, M. & Donachie, M. Referral for secondary restorative dental care in rural and urban areas of Scotland: findings from the Highlands & Islands Teledentistry Project. Br Dent J 192, 224–228 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4801339

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4801339

This article is cited by

-

Role of teledentistry in paediatric dentistry

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

Dental specialist workforce and distribution in the United Kingdom: a specialist map

British Dental Journal (2021)