Abstract

Aim The aim of the study was to find out to what extent children are involved in consenting to their dental care.

Methods It was conducted using a structured interview with 60 8–13-year-old children. In the control group, verbal consent was given by the parent, whilst in the study group written consent was given by the parent and verbal assent by the patient. Interviews were conducted after dental treatment.

Results The findings indicate that children in the study group felt they were more involved in deciding about their dental treatment compared with the control group.

Conclusion Children want to be more involved in consenting to their dental treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

A child must normally have the consent of a parent before they can obtain health care and advice. However, healthcare professionals are duty-bound to respect the evolving capacity and autonomy of the child and to consider the views of the child in all matters, including medical decision making. This does not imply that there is an age above which a child is automatically entitled to give consent, nor a universal age below which such consent is impossible. The issue is whether a child is capable of clearly understanding the nature and implications of any proposed treatment and is able and willing to make a decision1.

Childhood is the period of greatest change in life; it sees the maximum physical, emotional, social and psychological development. As children grow older, they should increasingly be allowed to make their own decisions. Even children who are not legally able to give consent to treatment should be consulted, enabling them to participate in the decision making process.

As children develop, the emphasis on obtaining consent/assent should be on the interactive process in which information is shared and joint decisions are made. With assent, children may verbally signify their agreement with their parents' written permission.2

A child's past experiences, educational experiences and basic general knowledge influences their decision-making ability. Previous experience of treatment may indicate sufficient understanding.3 By virtue of their own experience, they have greater understanding of their own condition and of the issues relevant to the decision that needs to be made. According to King and Cross4, children with chronic illnesses may be better equipped than their developmental peers to take part in decision making.

Brazier5 defines competence to consent as the ability of an individual to understand the nature, purpose and effects of proposed treatment. This involves comprehension and retention of information about treatment, believing the information and weighing up the information in the proper balance so as to arrive at a choice.

Implicit in the concept of consent is that the consent should be informed. To be informed a child should be able to understand the nature of treatment, the risks and seriousness of the procedure, the potential benefits, the alternatives, the possibility of refusing consent to treatment and the medical consequences resulting from such a refusal.

In most parts of the world, an individual is legally a minor and presumed incompetent until at least the age of 16 or even 18 years. Despite this, many children possess the capacity to take part in the decision-making process at some level.

Alderson6 investigated 120 school-age children due to have orthopaedic operations. She found that children under 10 years were able to grasp the concepts of treatment and its consequences, in fact some of them were better informed than their parents. Notably, these were elective, not life-saving operations, as indeed are most dental procedures. The consequences of refusing consent would have had no immediate effects. Alderson highlights the risk of under-estimating the child's ability to make wise and sensible choices. The danger of excluding them from the decision-making process may lead to resentful and angry children who have to live with the consequences of decisions in which they had no involvement.

Children whose parents afford them personal autonomy in decision making about family and personal matters may also be better prepared to take part in medical decisions than a child from a sheltered family. Every effort should therefore be made to reach a consensus, however protracted this process may be as long as it does not involve taking unacceptable risks with the child's future health. It may be better to delay treatment until the child is familiarized with consent.

Materials and methods

A study was conducted with the aim of investigating the extent to which children are involved in consenting to their dental care. The study had two main objectives.

-

To assess the ability and willingness of child patients to decide about their dental treatment

-

To determine whether following a defined consenting procedure makes any difference to children's attitudes to informed consent.

This study was carried out in the Department of Paediatric Dentistry at St Bartholomew's and the Royal London School of Medicine and Dentistry. The sample consisted of 60 subjects with an age range of 8–13 years. An interview schedule was designed and questions were asked based on general knowledge and previous experiences of dentistry. It also contained questions based on informed consent, ie on disclosure and understanding of information, the extent to which the children were involved and their willingness to consent to treatment.

Children not fluent in English, those who had treatment under sedation and general anaesthetic and those requiring emergency dental treatment were excluded from the study. Children fluent in English with intervals of no more than 2–3 weeks between their treatment and the interview were included.

All children were attending for routine treatment in the department. Interviews were carried out following dental treatment by the principal investigator (AA) with the parent present as an observer. The children were divided into two groups. The control group (n = 30) were interviewed after verbal consent was given by the parent. This was the normal procedure used in the department. The study group (n = 30) were interviewed after going through an additional process following a systematic procedure for consent in which written consent was given by the parent and verbal assent was given by the child patient.

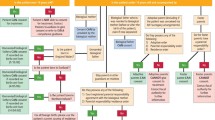

The guidelines for this additional process to be used in the study group were set out for the clinicians who carried out the treatment (Fig. 1).

The answers for the interview schedule were coded and entered directly into a statistical database (SPSS). The statistical significance of the comparative variables were tested using the chi-squared (Fisher exact) test.

Ethical approval to carry out this study was given by the local ethics committee.

Results

There were no significant differences between the two groups with respect to age, social class, ethnicity, dental awareness and gender. There were 19 females and 11 males in the control group and 14 females and 16 males in the study group, making a total of 60 children. Ninety per cent attended the dentist regularly, 97% had previously experienced dentistry, with a mean age of 5.6 years for their first visit to the dentist.

Findings from the whole group

Responses from all 60 children to the question, 'Who should talk to you about your treatment?' showed that more children (50%) wanted both the dentist and their parents to talk to them about their dental treatment, 38% felt that the dentist alone should talk to them and 12% felt it should be the parents alone. They believed that each person had their role to play in helping them to understand the nature of their treatment (Fig. 2).

When they were asked, 'Should children be involved in deciding about their dental treatment?', 75% of the children said they felt old enough to reason about the treatment and believed that children's views should be heard. Those who answered no to the question (17%) felt they were either too young to decide or did not want the responsibility and 8% answered, 'Don't know' (Fig. 3).

Comparison of the control and study groups

When asked how much information they had been given about their treatment, 73% of the control group said they had been given information of which 67% said it was enough. In the study group 100% of the children said they were given information about the treatment they had received and 83% said the information was enough (p < 0.05). When asked about their understanding of the information provided, 57% of the control group compared with 93% in the study group felt they fully understood the explanation.

Sixty-seven per cent of the control group compared with 90% of the study group preferred to have their treatment at the time rather

than later. Thirty-three per cent in the control group and 10% in the study group preferred to have treatment later, they felt they needed more time to decide (p < 0.05). All the children were happy with the treatment they had received, 43% of the control group expressed satisfaction with treatment, however, this level of satisfaction increased to 70% in the study group (p < 0.05). The control group felt able to give consent at a mean age of 11.8 years whilst for the study group, the mean age was 10.3 years (p < 0.05) (Table 1).

Of the control group, 50% said the dentist alone decided that treatment should be done whilst 13% said it was a joint decision between the dentist, parents and patient. This is compared to 43% of the study group who said the dentist alone decided and 33% said it was a joint decision (Table 2).

When asked who they felt should decide about treatment, 47% in the control group and 60% in the study group felt consent to treatment should be a joint decision between the dentist, the parent and the child (Table 3).

Discussion

The practicalities involved in obtaining consent are still largely unexplored in paediatric dentistry despite the fact that it has been a topical issue in recent years. However, dentistry remains an aspect of healthcare where there is often continual exposure throughout life. In many parts of the world, dentistry can thus be considered a part of life's experiences from childhood onwards. It appears that there has been a general increase in society's awareness of dental health and this means that more children are becoming dentally aware.

From the results of the study, most of the children had been exposed to dental care from an early age. These early experiences have influenced the views of children and often governed their attitude towards treatment as they grow older. It can be implied that given the opportunity, children who have previously had dental treatment might be able to decide for themselves as they can relate to their past experience of treatment.

Including children in their treatment decisions involves providing information, ensuring the adequacy of this information, checking that the explanation has been understood and the opportunity to make an informed choice has been created. The increased satisfaction reported by the children who had received the additional consent process indicate that improvements can be made when children are more fully involved.

In this study the children were asked if they understood the information given to them about their treatment. It showed that 57% of the control group felt they understood the information but this increased to 93% in the study group.

This demonstrates the positive trend observed in the responses of the patients following their participation in the additional systematic consent procedure.

In summary, the ability of children (and adults) to consent to treatment is related to the provision of adequate and comprehensible information. As children mature they want, and should be allowed, to make decisions for themselves about their dental treatment whilst continuing to look to the dentist and their parents for support. Since most dental procedures are neither emergency nor life-threatening, every opportunity must be given by health professionals and parents to nurture the development of a trusting relationship that is based on mutual respect in providing dental care for children. This helps promote the evolving autonomy of the child as they develop into responsible members of the society. Furthermore, children are likely to become more efficient in their decision making roles if given the chance to develop in an environment that is non-threatening when they make autonomous choices. Factors such as age, level of maturity, dental awareness and previous experience of treatment play an important role in enhancing the ability of children to consent to their own dental treatment.

Therefore, providers of dental care should recognize that they have a duty to involve children in consenting to their dental treatment thus enhancing their decision-making abilities from an early age.

Conclusions

The results from this study suggest that children want to be involved in the decision-making process and they want this to be in the form of a discussion between the dentist, their parents and themselves.

Children want adults to recognize and help promote their evolving autonomy by listening to them and acknowledging their contribution in consenting to dental care. This increases their understanding and satisfaction with their dental care.

References

Van Bueren G . The International Law on the Rights of the Child. Vol 35: pp 310–311. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1995.

Mouradian W E . Making decisions with children. Angle Orthod 1999; 69: 300–305.

Montogomery J . Health Care Law, pp 284 London: Oxford University Press, 1997.

King N M, Cross A W . Children as decision makers: Guidelines for paediatricians. J Pediatr 1989; 115: 10–16.

Montogomery J . Health Care Law, pp 230–231. London: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Alderson P . Children's consent to treatment. Br Med J 1994; 309: 1303.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Adewumi, A., Hector, M. & King, J. Children and informed consent: a study of children's perceptions and involvement in consent to dental treatment. Br Dent J 191, 256–259 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4801157

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4801157

This article is cited by

-

Exploring Child-Patient Autonomy: Findings from an Ethnographic Study of Clinic Visits by Children

Child Indicators Research (2024)

-

Who wears the braces? A practical application of adolescent consent

British Dental Journal (2015)

-

Social Vulnerability in Paediatric Dentistry: An Overview of Ethical Considerations of Therapeutic Patient Education

Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry (2014)

-

An audit of the level of knowledge and understanding of informed consent amongst consultant orthodontists in England, Wales and Northern Ireland

British Dental Journal (2008)