Key Points

In this part, we will discuss

-

Factors contributing to good RPD design

-

The dentist's input

-

The dental technician's input

-

Delegation of the dentist's responsibility

-

The work authorisation

Abstract

Factors contributing to good RPD design are described, including the respective inputs of the dentist and dental technician. Poor communication in current practice is reported and an appropriate format for a work authorisation presented.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

New publications: All the parts which comprise this series (which will be published in the BDJ) have been included (together with a number of unpublished parts) in the books A Cinical Guide to Removable Partial Dentures (ISBN 0-904588-599) and A Clinical Guide to Removable Partial Denture Design (ISBN 0-904588-637). Available from Macmillan on 01256 302699

In order to obtain the best possible results from removable partial denture treatment, it is essential that the dentist and dental technician work together effectively as a team. Each should have a sound understanding of the role of the other so that they can collaborate in an effective fashion.

-

The creation of an optimal RPD design is dependent on the following factors:

-

Clinical knowledge and training.

-

A thorough assessment of the patient.

-

Appropriate treatment planning including any mouth preparation.

-

Technical expertise and knowledge of the properties of materials.

Clearly the dentist's contribution is related primarily to the first three aspects while the technician's contribution is concerned with the fourth.

The dentist's input is founded on the following:

-

A knowledge of biological factors, pathological processes and the possible influence of mechanical factors on the masticatory system.

-

A knowledge of the patient's medical and dental history and an ability to appreciate, and to take account of, those aspects likely to be significant in RPD treatment.

-

An ability to undertake a thorough clinical examination and analysis of the oral environment.

-

An ability to modify the oral environment, eg by tooth preparation, periodontal and orthodontic therapy etc., to increase the effectiveness of the RPD treatment.

-

An ability to design an RPD which enhances, rather than compromises, oral function.

-

An ability to anticipate possible future oral changes which can then be taken into account when designing the RPD.

The technician's input is founded on:

-

The ability to translate two-dimensional design diagrams and written instructions into the three-dimensional reality of an RPD, according to accepted biological and mechani- cal principles.

-

The knowledge of appropriate techniques and materials to produce the finished RPD.

It is clearly essential that a dialogue between the two members of the team takes place so the expertise of both can be combined to ensure that the required outcome is achieved.

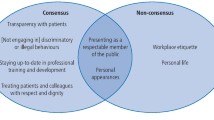

The roles of the dentist and the dental technician – the reality

In spite of the importance of the dentist in the RPD design process, numerous studies in several countries have demonstrated that there is widespread delegation of the responsibility for design by the dentist to the technician. There are probably many factors involved in this abrogation of the dentist's responsibility, but there is no doubt that it results in patients being provided with RPDs that do not take account of clinical and biological circumstances.

The work authorisation

In a number of countries, including the USA and Sweden, legislation states that the dentist has ultimate responsibility for all dental treatment, including the design and material of any prosthesis produced by dental laboratories. In the European Community, the Guidance Notes for Manufacturers of Dental Appliances (1994) of the Medical Devices Agency state that these devices (RPDs) are made in accordance with a duly qualified practitioner's written prescription which gives, under his responsibility, specific design characteristics. In the USA, State laws require a written Work Authorisation Order to accompany all work sent by a dentist to a dental laboratory.

It is obviously essential for effective communication that the dentist and technician have a clear understanding of each others terminology. Clarification of the design diagram may be achieved by using a colour code to identify different RPD components or functions. Since there is no universally agreed colour code in existence, agreement between the dentist and the technician on the meaning of any code is essential. One such example is a system based on the function of the RPD components:

-

Red – support.

-

Green – retention.

-

Blue – bracing/reciprocation.

-

Black – connection.

Good quality coloured annotated design diagrams can quickly be produced using a computerised knowledge-based system ('RaPiD', TMS Ltd, Aylesbury, UK) for RPD design. Design expertise incorporated in the software reacts if a mistake is made and guides the user to an acceptable design solution. The development of such computerised RPD systems introduces the possibility of on-line discussion between dentist and dental technician of RPD designs via the Internet. This form of tele-dentistry has potential as a useful new communications link between these two members of the dental team.

The design diagram

When producing a design diagram it is helpful to use a proforma, such as the example here, which includes the following information:

• Patient – name; registration number.

• Dental practice – practice address, telephone, fax, e-mail, clinician's name.

• Date of next appointment.

• Dental laboratory – laboratory address, telephone, fax, e-mail, job number; technician's name.

• RPD design diagram.

• RPD components, materials, specific instructions, eg type of articulator.

Any statement required by current legislation, eg those stipulated by the Medical Devices Agency.

However well the design diagram is produced, it still suffers from the significant limitation of being a two-dimensional representation of a three- dimensional object. Designs that appear entirely satisfactory in two- dimensions can be obviously in need of modification when seen in three dimensions. Also, subsequent transfer of two-dimensional information by the technician from the paper diagram to the three-dimensional cast can lead to errors of interpretation. Therefore, it is desirable for the dentist to transfer at least the outline of the major connector from the diagram to the study cast before sending both to the technician. In many cases there can be advantages if the dentist goes further and draws on the cast details of other components such as minor connectors, guide plates, clasps and occlusal rests.

Sometimes a patient may present with an RPD that has given satisfactory service for many years but is now 'worn out'. A study cast obtained from an impression of the old denture in situ will provide clear details of the connector outline and sometimes also the location of other components which will provide a useful reference when designing and fabricating the replacement denture.

Verbal communication

However thorough the dentist is in providing the technician with details of an RPD design together with all the supporting records, it is possible that the technician will still sometimes need additional information or clarification. Under such circumstances the value of discussing the case face-to-face, if the technician works on the premises, or on the telephone if the laboratory is elsewhere, cannot be underestimated.

Apparently insurmountable difficulties can then evaporate. Each participant can acquire a far better understanding of the work of the other and in the process forge stronger team links and become a significantly better healthcare worker as a result. Increasingly, electronic links such as e-mail and the Internet are likely to become more widely used for such communication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Davenport, J., Basker, R., Heath, J. et al. Communication between the dentist and the dental technician. Br Dent J 189, 471–474 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800803

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800803

This article is cited by

-

Work-related psychosocial demands related to work organization in small sized companies (SMEs) providing health-oriented services in Germany – a qualitative analysis

BMC Public Health (2022)

-

Should dental technicians play a greater role in the education of foundation dentists?

British Dental Journal (2020)

-

Is the shortened dental arch still a satisfactory option?

British Dental Journal (2017)

-

Communication methods and production techniques in fixed prosthesis fabrication: a UK based survey. Part 1: Communication methods

British Dental Journal (2014)

-

Communication methods and production techniques in fixed prosthesis fabrication: a UK based survey. Part 2: Production techniques

British Dental Journal (2014)