Abstract

Objective To determine the relationships between working conditions for new dental graduates and their mental and physical health.

Design A cross-sectional postal survey.

Subjects Graduates from the years 1991 and 1994 were selected to provide cohorts before and after the introduction of mandatory vocational training. A total of 232 graduates were sent questionnaires and 183 replied (77%): 90 men (49%) and 93 women (51%).

Setting The cohorts came from all Scottish dental schools. When surveyed in 1996/1997, 66% were working in Scotland and 28% were in England. The rest were elsewhere in the UK or abroad.

Measures Measures included a wide range of conditions at work: number of patients seen, pace of work, hours worked, attitudes to work, financial arrangements, alcohol consumption, sickness-absence, physical and mental health.

Results There were significant differences between those working in general practice and those in hospital in terms of the hours, number of patients seen, feelings of competence and senior support. Methods of payment for treatment in general practice also revealed differences in perception of work: most pressure at work was associated with part NHS and part private funding. Mental health and alcohol consumption were equivalent to age-matched junior doctors, but increased psychological symptoms in female dentists were significantly associated with the number of units of alcohol consumed.

Conclusion Selected working conditions are associated with reported competence, stress and health among young dentists.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Research findings suggest that dentists suffer high rates of stress1 but working conditions may affect practitioners in different ways. There are data which show that dentists identify the same sources of stress regardless of the system for payment, but that those working outside the National Health Service (NHS) are under less time pressure and face less paperwork.2 Recent work by Wilson et al. shows the growing pressure of working within the constraints of the NHS.3 Specific features in the working environment are associated with different aspects of 'burnout'4,5 although personal characteristics may affect how individuals respond; eg female dentists may react differently from male dentists. In medicine, it has been shown that women doctors are more vulnerable than their male counterparts, especially in hospital practice.6 However, in dentistry, Cooper et al.1 suggest an opposite effect of gender. When comparing dentists with other professional groups, they found that men's levels of symptoms were more elevated than those of the women, although it was suggested that women may face greater difficulty later in their careers.

For dental graduates entering primary care, the abrupt change from student to dental practitioner has been eased in recent years by the introduction of mandatory vocational training. There is evidence that this has been largely successful in fulfilling its aims7 but for many this transitional period is a testing time. There is little information available on the workload of newly qualified dentists, the financial burdens that they carry, or on how these challenges affect their perception of dentistry, their health and well-being.

This paper is extracted from a larger comprehensive study of newly qualified dentists examining a wide range of work and personal variables.7,8 The subjects were all graduates from Scottish dental schools, but since 30% were working elsewhere in the UK at the time of the survey, and since a third had worked outside Scotland in the past, their experience also relates to dental practice in the rest of the UK. Reported here are the findings on workload, finance, perception of work and of health. The specific aims of this report are to describe the working conditions for young dentists (including financial factors); to identify which conditions are associated with attitudes to work; to identify differential effects by gender and by cohort (pre- or post mandatory VT) and to measure the associated health of the dentists. It is hoped that this work will help inform the development of vocational training and the planning of continuing dental education for young graduates.

Methods

A postal questionnaire was designed to collect the relevant data at the end of 1996 from two cohorts of graduates from all Scottish dental schools. The years chosen were 1991 and 1994: one cohort qualifying just before the introduction of mandatory vocational training, and the second cohort qualifying just afterward. Participants were asked about current conditions at work, their attitudes to work,9 financial arrangements, alcohol consumption and health.10 There was space at the end for open comments. Further details of the methodology are available in Baldwin et al.8 This paper presents data on working conditions, health and welfare.

The postal questionnaire was derived from the 'attitudes to work'9 and the 'general health'10 questionnaires which have been widely used in medicine.6

The 'attitudes to work' questionnaire9 has 25 statements covering feelings of competency, relationships with senior staff, satisfaction with work etc, which the subject rates on a 5-point scale from 'strongly disagree' to 'strongly agree'. For a description of attitudes, the responses to individual items are presented but for correlations with other variables, the data were reduced by factor analysis by varimax rotation.11 Seven significant factors emerged, the first three factors accounting for 38% variance. These are used to test relationships between working conditions and associated attitudes to work as a dentist.

-

Factor 1 (eigenvalue = 5.04) was the feeling of competence and effective learning with high loadings for 'I am developing new skills', 'I use my skills to the full in my job' and 'I am satisfied with the variety in my job' (Alpha coefficient = 0.59)

-

Factor 2 (eigenvalue = 2.5) was the feeling of having too much responsibility combined with a fear of making mistakes. It had high loadings on the following items: 'I am under great pressure at work', 'I am afraid of making mistakes', 'I am afraid of litigation' and 'The responsibilities of my job are overwhelming' (Alpha coefficient = 0.75)

-

Factor 3 (eigenvalue = 1.78) was satisfaction with dentistry and colleagues and had high loadings for 'I am very satisfied with my choice of dentistry as a career', 'I can discuss work problems with other colleagues', 'I have been properly trained for my job' and 'I can discuss personal problems with other colleagues' (Alpha coefficient = 0.53).

The 28-item, scaled 'general health' questionnaire (GHQ-28)10is a screening device for psychological and psychosomatic symptoms, and has been widely used for surveys of the general population. It can be scored in two ways: a binary scoring (0011) is used to determine the level of psychiatric 'caseness' in a population and a Likert scale (0123) is used for correlations with other variables. Both methods are used here. Additionally, the dentists were asked to complete a purpose-designed table, recording how much alcohol they had drunk on each day of the previous week and the circumstances in which they had done so. A key to the number of units contained in different types of drink was supplied. Since the last week may have been atypical, they were also asked to describe themselves as habitually teetotal, light, moderate or heavy drinkers.

Data were analysed using non-parametric tests from SPSS for Windows.11 Results are reported as significant where P < 0.05.

Results

There were 139 graduates in 1991, and 102 graduates in 1994, of whom one was known to have died and one had been removed from the Dentists Register. Seven could not be traced to any confirmed address. A total of 232 graduates were sent questionnaires and 183 replied (77%).

The respondents comprised 90 men (49%) and 93 women (51%): the median age of the 1990/91 graduates was 28 years (range =26–39) and of the 1993/94 graduates it was 25 (range = 23–29). In terms of their personal circumstances, 40% were married, 24% were living with a partner and 36% were single.

With regard to their working environment, 76% were in general dental practice; 13% were in hospital dentistry and 4% were in university posts; the rest were in a variety of posts, were not currently practising or did not answer this question. The majority (85%) were working full-time. There were no significant gender differences in these proportions. Two-thirds (66%) of the sample were working in Scotland at the time of the survey, but 30% were elsewhere in the UK and 4% were abroad. Further details can be obtained from the study by Baldwin et al.8

Number of patients

The dentists were asked to indicate approximately how many patients they had seen during the preceding week — whether or not this had been typical. Taking only those on full-time contracts, the distribution of their responses is shown in figure 1, which also compares those working in hospital with those in general practice. There were no significant gender differences in these numbers, nor were there differences between the 1991 and 1994 graduates. Dentists working in general practice, however, saw more patients: a mode of 101–150 in the last week, compared with a mode of 0–50 in hospital (Mann-Whitney U-test, U = 382, P < 0.001).

Hours worked in the last week

For those on full-time contracts in general practice or hospital (N = 135), the mean number of hours worked in the last week was 38.6. There were no significant gender differences in the hours worked, but the 1994 graduates worked significantly longer hours: a mean of 40.8 compared with 36.9 hours for 1991 graduates (Mann-Whitney U-test, U = 1737, P = 0.003). Since both groups were seeing around the same number of patients, it is likely that the 1994 graduates are working a little more slowly than the older dentists. The distribution of responses is in figure 2.

Longer hours were worked by those in hospital: a mean of 50 compared with 36 in general practice (Mann-Whitney U-test, U = 911, P = 0.03). Some felt this was a strain:

'When I applied to train as a dentist, I did not envisage that I would still be training and studying 11 years later, nor did I expect to find myself working in a hospital ward doing a similar job to a junior doctor and working unsociable hours in an 'on-call' situation'.

For those working on part-time contracts, the median of hours worked in the last week was 24 (range = 4–118). From the comments that these dentists made elsewhere on the questionnaire, this wide variation seems to be because of their occasionally doing other work, or taking on a locum position. There was no difference in any of the factors derived from the 'attitudes to work' scale between those on full-time against those on part-time contracts, even when women were analysed separately.

Pressure of work

The dentists were asked two further questions about the pressure at work: how often in the last week they had missed a lunch break through pressure of work; and how often they had run at least 30 minutes late in their appointments.

A quarter of the graduates had missed lunch once or more in the last week, and half the sample had run late once or more in the last week. There were no differences in gender, and no differences by year of graduation.

Finance

Since young dentists often have to take on loans in order to complete training and set up in practice, they were asked about past and present financial circumstances. When asked about past debt, not all respondents answered this question, but the answers of the 179 (98%) who did appear in Table 1. Thirty-four per cent of the sample had no debt or less than £1000 of debt at graduation, but more than half had an outstanding loan of £1000 or more and, surprisingly, 16% owed more than £5000 at graduation.

Current financial arrangements

They were also asked about their current financial arrangements and 178 replied. Of these, 60% had an outstanding loan, and the mean sum was £17,369. There was no significant difference in the amounts between those working in general dental practice and those working elsewhere. The distribution appears in Table 2. Of particular note is the fact that 5% of the graduates had loans in excess of £100,000.

The dentists were asked to say how much financial arrangements were a source of stress. Results for the whole group are in Table 3. The majority (72%) described their financial arrangements as not at all or only slightly stressful. There was a significant relationship between the size of the current debt and the level of stress reported (Spearman Rank correlation, r = +0.31, P = 0.002). However, the size of the debt was not related to any of the mental health scores.

Men had taken on significantly higher loans: a mean of £24,000 compared with £7000 for women (Mann-Whitney U-test, U = 509, P = 0.007). They also found financial arrangements more stressful (Mann-Whitney U-test, U = 3207, P = 0.01). There were no significant differences in the size of the loan or the stress, according to year of graduation.

Finance in general practice

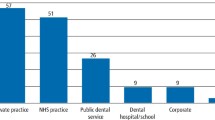

For those in general practice, they were asked to describe how payments were made in their practice. There were 140 dentists in general practice at the time of the survey: not all these respondents completed both sections of this question, but for those that did, their answers appear below in Table 4.

The young dentists reported a move away from NHS finance in their practices. Those who were funded partly by the NHS and partly by independent means reported significantly more pressure at work than those who were wholly NHS (Item 6 on the 'attitudes to work' scale, Mann-Whitney U-test: U = 1615, P = 0.02). Those who were fully independent reported least pressure. These differences, however, were not reflected in different levels of psychological symptoms. The dentists seemed to have found the method of payment for dental care an unexpected source of difficulty:

'In the particular area where I work, I find it quite depressing having to radically alter treatment plans around the patient's financial circumstances, and find this quite a stress in the job'.

'Although money wasn't a factor in choosing dentistry, it seemed to be a way of making a good living whereas now the financial reward appears to be on a downward spiral while workload and patient expectations are rising exponentially... It can't be right that those who milk the system and provide high volume work and cut corners, double-book patients and constantly run late are the ones who benefit most from NHS dentistry, in financial terms anyway'.

Attitudes to work

The 'attitudes to work' scale covers the dentist's perception of a range of aspects of the working environment. The responses to each item are shown first in Table 5, with subsequent analysis of group differences. Factors derived from these items are used for correlations.

On the whole, the young dentists had a very positive attitude to their work and chosen career. However, the areas of concern that this table identifies are the feeling of being under pressure at work (item 6), the fear of litigation and making mistakes (items 9 and 10), and the belief that patients can be too demanding (item 15).

Pressure of work seems to come from the combined effects of number of patients to be seen, practice administration and the financial organisation required — something many graduates had not expected:

'Undergraduate training in no way prepares you for general practice, ie the number of patients seen in a day; the financial implications of not seeing enough patients; finances in general (taxation, national insurance, etc); what to expect as an associate (getting the best contract)'.

'A lot more stressful than I thought. Unaware that I would be ultimately responsible for everything that goes on in my surgery — even the nurse. Very intricate work in a confined space, and a majority of nervous patients! Unaware of paperwork. Unaware of constraints of working in the NHS'.

The fear of making mistakes and litigation is something that clearly affects the graduates:

'The main source of stress at the moment is fear of litigation (although I am very careful, I am only human)'.

'Patients are much more medico-legally aware and can often question the opinion of the dentist'.

This is also reported by young doctors12 and is likely to be a reflection of the current, changing relationship between healthcare practitioners and the public.

'Patients can be too demanding' This statement attracted agreement from 87% of the sample. This perception is often associated in other health professionals with aspects of 'burnout', when staff disengage from patients. It is usually thought of as a cumulative effect of constant contact with patients, and something which happens in later career.12 Here it seems to be a reflection of the fact that dental patients are less compliant than expected, something for which the young dentists indicated in their comments they were unprepared:

'Patients are more demanding and not as appreciative as I had thought'.

'Didn't think it would be as stressful and patients as demanding'.

'I didn't know just how awkward the people attached to teeth could really be!'

'The dentistry is not difficult. The hardest thing was learning to deal with demanding patients'.

The individual items representing these three areas of concern were tested to see if they related to mental health symptoms as measured by the GHQ-28. There were significant relationships with all of them, shown in Table 6.

Gender differences in attitudes to work

There were significant gender differences in some of these attitudes (Mann-Whitney U-tests) even though overall, most people were in positive agreement with the statements listed below.

Men agreed significantly more strongly with the following statements:

-

'I use my skills to the full in my job' (U = 3077, P = 0.01)

-

'I am confident of my abilities' (U = 2914, P = 0.002)

-

'I am very satisfied with my choice of dentistry as a career' (U = 3130, P = 0.02)

-

'I have never experienced bias on account of gender' (U = 3090, P = 0.02)

Women agreed significantly more strongly in their endorsement of the following:

-

'I am afraid of litigation' (U = 3164, P = 0.03)

-

'I have sometimes been bullied by senior colleagues' (U = 3005, P = 0.008).

Cohort differences in attitudes to work

Although all dentists agreed with the statement: 'I am useful most of the time' the 1991 graduates agreed significantly more strongly (U = 3170, P = 0.02). This almost certainly represents the extent to which learning and the development of skills continues to take place in the first 5 years of practice.

The effects of working conditions on attitudes to work

Place of work: Although there were comparatively few of the sample who were working in hospital (N = 26) at the time of the survey, they showed some significant differences in terms of their attitudes to work. For these comparisons, the factors derived from the 'Attitudes to work' questionnaire are used. Those in hospital scored significantly higher than those in general practice on Factor 1 'Feelings of competence' (U = 887, P = 0.0006) and significantly lower than those in general practice on Factor 2 'Too much responsibility' (U = 996, P = 0.003). In other words they felt both more competent and better supported.

Number of patients: Overall, there was a relationship between number of patients and feelings of competence. The fewer the patients seen in the preceding week, the greater the feeling of competence (Factor 1, r = – 0.15, P = 0.04, Spearman Rank Correlation). However, this association disappeared when hospital and general practice dentists were analysed separately and is likely to be a function of other aspects of the setting, such as the level of professional support, as indicated above. Nevertheless, a number of general practice respondents commented on the volume of work:

'The time pressures — unable to spend time on quality dentistry within the NHS'.

Health

Sickness-absence

The dentists were asked about sickness-absence. They had taken very little sick leave, a mean of 2 days off in the last year. They had come to work unfit (when they would have advised a friend or colleague in the same state to stay at home) for a mean of 5 days in the last year. This last measure was significantly associated with mental health symptoms (r = +0.32, P < 0.001), and with Factor 1 'feelings of competence' (r = -0.22, P = 0.004). In other words, the more competent and mentally robust they felt, the fewer days of illness they reported. There were no differences by gender or year of graduation.

Mental health

Overall, using the binary system of scoring for the GHQ-28, 30% of the sample had significant psychological symptoms, ie they were above the 3/4 threshold for 'caseness'. There were different levels according to gender: 34% of women and 26% men, but this was not statistically significant (chi-square). There were no significant differences according to year of graduation. This level of 'caseness' is virtually identical to a directly comparable cohort of Scottish medical graduates from 1991, for whom the level of caseness using exactly the same measure at the same time, was 31%.6

Mental health scores were significantly related to the factors derived from the 'attitudes to work' questionnaire, as shown in Table 7. These results show that the more competent the dentists felt, and the more satisfied they were, the fewer psychological symptoms reported. By contrast, the more they were afraid of litigation and making mistakes, the more symptoms they reported. Psychological symptoms were also significantly associated with the days at work but unfit (r = +0.32, P < 0.001).

Alcohol consumption

Subjects were asked to record a drinking diary for the preceding week: where, with whom, and how many units of alcohol they had consumed each day. The units were then totalled for the week. They had drunk an average of 13 units in the preceding week, but there was a gender difference, with men drinking significantly more: a mean of 17 units, compared with 10 for women (Mann-Whitney U-test U = 2992, P = 0.002). There were no differences by year of graduation. The distribution of alcohol consumption is shown in figure 3.

Since alcohol consumption in the preceding week may not have been typical, the dentists were also asked to describe themselves as 'teetotal', 'light', 'moderate' or 'heavy' drinkers; the results are in Table 8. Also in the table are the mean number of units consumed in the last week by the dentists within each group, with men and women shown separately.

Table 8 shows that for both men and women, the amount of alcohol consumed in the last week by 'light' drinkers is just under half the recommended maximum quantity (21 units for men and 14 units for women)13 whereas the 'moderate' drinkers had consumed more than the maximum weekly limit. As an illustration, 11 men who said that they were 'moderate' drinkers had consumed between 32 and 54 units, roughly between 5 to 8 bottles of wine, in the preceding week. This suggests that they may seriously underestimate the amount that they habitually drink. For men, there was no correlation between how much they drank and their mental health. However, for women there was a significant relationship: the more psychological symptoms reported (higher scores on the GHQ-28), the more they drank (r = +0.35, P = 0.001).

Discussion

The description of the working conditions of this group of young dentists raises a number of issues. The cohorts were 3 and 6 years after graduation and still very much in the formative years of practice.14 The results suggest two factors that are associated with learning and the acquisition of skills. The first is the pace at which the dentists found themselves working. The process of learning and improving skills requires not only practical clinical experience, but some time for reflection. The volume of work in general dental practice reported here suggests that the graduates have little time for reflection. The finding that those working in hospital see fewer patients with more senior support, and that they feel more competent, underlines the importance of working at an appropriate pace with appropriate supervision. General professional training with a second year in a supported environment will be extremely important and beneficial in providing more time for the graduate to develop and reflect upon clinical skills and experience.

The second concern is the level of debt and the associated stress which the dentists, particularly men, experience. Although around only a quarter of the sample were experiencing such stress, for them this stress must exert considerable pressure to increase their workload. The small number of dentists who graduate with high levels of debt are likely to be particularly at risk. It is highly likely that the recent proposals by the Government to introduce tuition fees will add to this debt and hit dental students particularly hard.

Money also causes problems for graduates in terms of the methods of payment that patients make. Least pressure was reported by those working outside the NHS, followed by those who were wholly NHS funded. The most difficult arrangement appears to be part NHS and part privately funded. This may be because it highlights the discrepancy between 'optimal' treatment which is not constrained by NHS regulation, and the procedures which are permitted under NHS funding. The free comments highlighted how uncomfortable the graduates felt with these restrictions. This confirms recent findings from a comprehensive survey, sampling dentists currently working in the UK.3 They ranked 'working within the constraints of the NHS' third in a list of potential stressors.

The fear of making mistakes and of litigation is a significant feature of their working lives. It is part of the present culture, as is the fact that patients are more demanding of staff in the health professions. Both these features are associated with increased psychological symptoms. There is little that can be done to alleviate this distress. The fear of making mistakes will diminish only with increased competence and confidence. One hopes that the dentists adjust to their patient population without experiencing the emotional cut-off or blunting that represents 'burn-out'. There must be a role for the postgraduate education system in recognising this need and in tailoring support appropriately. It is hoped that the recent proposals by the General Dental Council15 to introduce recertification based upon participation in postgraduate dental education can be used constructively to address this issue.

The gender differences revealed by these results are in keeping with others in the medical profession. The increased confidence of the male dentists is also evident in young doctors6 and in the general population. The female dentists were more afraid of litigation and reported more experience of bullying. Again these results show similarities with female doctors.6

The undergraduate curriculum and subsequent vocational training still does not seem to have prepared the young dentists for the administrative responsibilities that running a practice entails. This situation may improve with the increased time which will be available in general professional training. Another area which seems to be to some extent neglected is the management of the psychological difficulties presented by dental patients. There is little in the undergraduate curriculum to prepare students for this16 and although this issue is addressed in the General Dental Council's17 recommendations for the undergraduate curriculum, both students and trainees might benefit from further training in the clinical skills required for the management of highly anxious, hostile or distressed patients.

The dentists take very little sick leave (an average of 2 days per year), and they come to work when they are unfit for an average of 5 days in the year. This suggests that the pressure not to cancel patients, or to keep earning, forces them to work through illness. Their mental health is comparable to that of junior doctors, but both groups show more symptoms than the general population.12 With the dentists, better health is associated with increased feelings of competence, satisfaction with dentistry and support from other dental colleagues. This finding has an important implication for those managing postgraduate education and peer review and again there is great scope within a system of recertification to address this issue.

Alcohol consumption in the dentists is also comparable to that of age-matched junior doctors, but the fact that increased psychological symptoms are associated with increased alcohol intake in the female dentists is a matter of concern. It suggests that alcohol may be used as a means of coping with stress, and this is a dangerous habit to establish at such a young age. The women reported lower levels of confidence and higher levels of fear of litigation, but otherwise they did not appear to be suffering significantly more than their male counterparts. Perhaps their use of alcohol is effective in keeping symptoms under control.

In these cohorts of young dentists, a variety of working conditions have been shown to be associated with specific attitudes to work. These attitudes are in turn associated with aspects of health. There are important implications for the undergraduate curriculum, in terms of the content of training, and more extensively for all those involved in postgraduate dental education. The results suggest that improvements in working conditions and in the level of professional support are likely to be associated with benefits in competence and health among young dentists.

References

Cooper C L, Watts J, Kelly M . Job satisfaction, mental health, and job stressors among general dental practitioners in the UK. Br Dent J 1987; 162: 77–81.

Newton J T, Gibbons D E . Stress in dental practice: a qualitative comparison of dentists working within the NHS and those working within an independent capitation scheme. Br Dent J 1996; 180: 329–334.

Wilson R F, Coward P Y, Capewell J, Laidler T L, Rigby A C, Shaw, T J . Perceived sources of occupational stress in general dental practitioners. Br Dent J 1998; 184: 499–502.

Osborne D, Croucher R . Levels of burnout in general dental practitioners in the south-east of England. Br Dent J 1994; 177: 372–377.

Humphris G, Lilley J, Kaney S, Broomfield D . Burnout and stress-related factors among junior staff of three dental hospital specialties. Br Dent J 1997; 183: 15–21.

Baldwin P J, Dodd M, Wrate R M . Young doctors: work, health and welfare. A class cohort 1986–1996. Report for the Department of Health, R&D Division, London, 1997.

Baldwin P J, Dodd M, Rennie J S . Postgraduate dental education and the 'new'graduate. Br Dent J 1998; 185: 591–594.

Baldwin P J, Dodd M, Rennie J S . Career and patterns of work of Scottish dental graduates 1991 and 1994. Br Dent J 1998; 185: 238–243.

Firth-Cozens J . The role of early family experiences in the perception of organisational stress: Fusing clinical and organisational perspectives. J Occupational Organizational Psychol 1992; 65: 61–75.

Goldberg D P, Hillier V F . A scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire. Psychol Med 1979; 9: 139–145.

Norusis M J . SPSS for Windows. Release 6.0 Chicago: SPSS Inc., 1993.

Firth-Cozens J . Stress in doctors: a longitudinal study. Report for the Department of Health, R&D Division, London, 1995.

The Royal Colleges of Physicians, Psychiatrists and General Medical Practitioners. Alcohol and the heart in perspective: Sensible limits reaffirmed. London, 1995.

Chambers D W, Wellington R L . Practice profile: the first twelve years. Can Dent Assoc J 1994; 22: 25–32.

Reaccreditation and recertification for the dental profession. London: The General Dental Council, 1997.

Atkinson J M, Millar K, Kay E J, Blinkhorn A S . Stress in dental practice. Behav Sci in Dentistry 1991; 3: 60–64.

The first five years. The undergraduate dental curriculum. London: The General Dental Council, 1997.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Scottish Council for Postgraduate Medical and Dental Education. We are very grateful to all the dentists who took part.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Baldwin, P., Dodd, M. & Rennie, J. Young dentists — work, wealth, health and happiness. Br Dent J 186, 30–36 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800010

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800010