Abstract

PSA testing has made prostate cancer screening a reality for men in many parts of the world, but its benefit for men's health continues to be debated. In men exposed to PSA testing, there has been a well-documented change in the presentation of prostate cancer with a shift towards earlier pathological stage, not without justifiable concern about over-diagnosis by prostate biopsy. Increasingly, men now diagnosed with early stage cancer have previous PSA exposure and are selected for biopsy based on PSA change in relation to cutoff values. Some recent observations suggest that PSA may no longer be an effective marker for early stage tumours, with PSA elevation failing to discriminate tumour-specific characteristics from benign gland enlargement. Traditionally, variation in pathological stage of clinically localised prostate cancer at diagnosis has related to clinical stage, PSA and biopsy Gleason grade, but with distinctions based upon these three assessments declining and an increasing proportion of organ-confined tumours at presentation, new methods of cancer detection and prognostic assessment are now required. Molecular technologies hold great promise in this respect, and in the future biomarker signatures are likely to overshadow total PSA for guiding early diagnosis and prognostic assessment. While arguments about prostate screening will continue, owing not least to its feasibility, future debate is likely to focus increasingly on technological advances and molecular profiling of these notoriously heterogeneous tumours.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 4 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $64.75 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Parkin DM, Whelan SL, Ferlay J, Teppo L . Cancer Incidence in Five Continents. Vol. VII. IARC Scientific Publication: Lyon, 1997.

Gronberg H . Prostate cancer epidemiology. Lancet 2003; 36: 859–864.

Cancer research UK. Prostate Cancer Stats 2002. Cancer Research UK: London.

Amelar RD, Dubin L . Semen Analysis, In Male Infertility. W.B. Saunders, 1997.

Wilson JMG, Jungner G . Principles and Practice of Screening. WHO: Geneva, 1968.

Chamberlin J, Melia J, Shearer RJ, Eeles R, Muir G, Stratton M et al. Prostate cancer. Lancet 1993; 342: 901–905.

Breslow N, Chan CW, Dhom G, Drury RA, Franks LM, Gellei B et al. Latent carcinoma of prostate at autopsy in seven areas. Int J Cancer 1977; 20: 680–688.

Whitmore Jr WF . Localised prostatic cancer: management and detection issues. Lancet 1994; 343: 1263–1267.

Krumholtz JS, Carvalhal GF, Ramos CG, Smith DS, Thorson P, Yan Y et al. Prostate-specific antigen cutoff of 2.6 ng/mL for prostate cancer screening is associated with favourable pathologic tumor features. Urology 2002; 60: 469–473.

Partin AW, Yoo J, Carter HB, Pearson JD, Chan DW, Epstein JI et al. The use of prostate specific antigen, clinical stage, and Gleason Score to predict pathological stage in men with localized prostate cancer. J Urol 1993; 150: 110–114.

Partin AW, Kattan MW, Subong EN, Walsh PC, Wojno KJ, Oesterling JE et al. Combination of prostate-specific antigen, clinical stage, and Gleason score to predict pathological stage of localized prostate cancer. A multi-institutional update. JAMA 1997; 277: 1445–1451.

Partin AW, Mangold LA, Lamm DM, Walsh PC, Epstein JI, Pearson JD . Contemporary update of prostate cancer staging nomograms (Partin Tables) for the new millennium. Urology 2001; 58: 843–848.

Kattan MW, Shariat SF, Andrews B, Zhu K, Canto E, Matsumoto K et al. The addition of interleukin-6 soluble receptor and transforming growth factor beta1 improves a preoperative nomogram for predicting biochemical progression in patients with clinically localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2003; 21: 3573–3579.

Parkes C, Wald NJ, Murphy P, George L, Watt HC, Kirby R et al. Prospective observational study to assess value of prostate specific antigen as screening test for prostate cancer. BMJ 1995; 311: 1340–1343.

Hakama M, Stenman UH, Aromaa A, Leinonen J, Hakulinen T, Knekt P . Validity of the prostate specific antigen test for prostate cancer screening: followup study with a bank of 21 000 sera in Finland. J Urol 2001; 166: 2189–2191.

Coley CM, Barry MJ, Fleming C, Mulley AG . Early detection of prostate cancer. Part I: Prior probability and effectiveness of tests. The American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 1997; 126: 394–406.

Woolf SH . Screening for prostate cancer with prostate-specific antigen. An examination of the evidence. N Engl J Med 1995; 333: 1401–1405.

Richardson TD, Oesterling JE . Age-specific reference ranges for serum prostate-specific antigen. Urol Clin North Am 1997; 24: 339–351.

Catalona WJ, Partin AW, Slawin KM, Brawer MK, Flanigan RC, Patel A et al. Use of the percentage of free prostate-specific antigen to enhance differentiation of prostate cancer from benign prostatic disease: a prospective multicenter clinical trial. JAMA 1998; 279: 1542–1547.

Mikolajczyk SD, Rittenhouse HG . Tumor-associated forms of prostate specific antigen improve the discrimination of prostate cancer from benign disease. Rinsho Byori 2004; 52: 223–230.

Catalona WJ, Bartsch G, Rittenhouse HG, Evans CL, Linton HJ, Horninger W et al. Serum pro prostate specific antigen preferentially detects aggressive prostate cancers in men with 2–4 ng/ml prostate specific antigen. J Urol 2004; 171 (Part 1): 2239–2244.

Stamey TA, Caldwell M, McNeal JE, Nolley R, Hemenez M, Downs J . The prostate specific antigen era in the United States is over for prostate cancer: what happened in the last 20 years? J Urol 2004; 172: 1297–1301.

Thompson IM, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, Lucia MS, Miller GJ, Ford LG et al. The influence of finasteride on the development of prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 215–224.

Khan MA, Carter HB, Epstein JI, Miller MC, Landis P, Walsh PW et al. Can prostate specific antigen derivatives and pathological parameters predict significant change in expectant management criteria for prostate cancer? J Urol 2003; 170: 2274–2278.

D’Amico AV, Chen MH, Roehl KA, Catalona WJ . Preoperative PSA velocity and the risk of death from prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 125–135.

Pound CR, Partin AW, Epstein JI, Walsh PC . Prostate-specific antigen after anatomic radical retropubic prostatectomy. Patterns of recurrence and cancer control. Urol Clin North Am 1997; 24: 395–406.

Feneley MR, Landis P, Simon I, Metter EJ, Morrell CH, Carter HB et al. Today men with prostate cancer have larger prostates. Urology 2000; 56: 839–842.

Catalona WJ, Smith DS . Cancer recurrence and survival rates after anatomic radical retropubic prostatectomy for prostate cancer: intermediate-term results. J Urol 1998; 160 (Part 2): 2428–2434.

Zincke H, Oesterling JE, Blute ML, Bergstralh EJ, Myers RP, Barrett DM et al. Long-term (15 years) results after radical prostatectomy for clinically localized (stage T2c or lower) prostate cancer. J Urol 1994; 152 (Part 2): 1850–1857.

Lu-Yao GL, Yao SL . Population-based study of long-term survival in patients with clinically localised prostate cancer. Lancet 1997; 349: 906–910.

Holmberg L, Bill-Axelson A, Helgesen F, Salo JO, Folmerz P, Haggman M et al. A randomized trial comparing radical prostatectomy with watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 781–789.

Oliver SE, May MT, Gunnell D . International trends in prostate-cancer mortality in the ‘PSA ERA’. Int J Cancer 2001; 92: 893–898.

George N In: Mundy AR, Fitzpatrick JM, Neal DE, George NJR (eds). Screening in Urology. In: The Scientific Basis of Urology. Isis Medical Media: Oxford, 1999.

Gohagan JK, Prorok PC, Kramer BS, Hayes RB, Cornett JE . The prostate,lung,colorectal, and ovarian cancer screening trial of the National Cancer Institute. Cancer 1995; 75: 1869–1873.

Crawford ED . PSA testing interval: data from PLCO screening trial. American Society of Clinical Oncology Abstracts (4); May 18-21, 2002.

Schröder FH . The European screening study for prostate cancer. Can J Oncol 1994; 4 (Suppl): 102–109.

Draisma G, de Koning HJ . MISCAN: estimating lead-time and over-detection by simulation. BJU Int 2003; 92 (Suppl 2): 106–111.

Labrie F, Candas B, Dupont A, Cusan L, Gomez JL, Suburu RE et al. Screening decreases prostate cancer death: first analysis of the 1988 Quebec prospective randomized controlled trial. Prostate 1999; 38: 83–91.

Bartsch G, Horninger W, Klocker H, Reissigl A, Oberaigner W, Schonitzer D et al. Prostate cancer mortality after introduction of prostate-specific antigen mass screening in the Federal State of Tyrol, Austria. Urology 2001; 58: 417–424.

Stanford JL, Feng Z, Hamilton AS, Gilliland FD, Stephenson RA, Eley JW et al. Urinary and sexual function after radical prostatectomy for clinically localized prostate cancer: the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. JAMA 2000; 283: 354–360.

Siegel T, Moul JW, Spevak M, Alvord WG, Costabile RA . The development of erectile dysfunction in men treated for prostate cancer. J Urol 2001; 165: 430–435.

Weldon VE, Tavel FR, Neuwirth H . Continence, potency and morbidity after radical perineal prostatectomy. J Urol 1997; 158: 1470–1475.

Steineck G, Helgesen F, Adolfsson J, Dickman PW, Johansson JE, Norlen BJ et al. Quality of life after radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 790–796.

Yao SL, Lu-Yao G . Population-based study of relationships between hospital volume of prostatectomies, patient outcomes, and length of hospital stay. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999; 91: 1950–1956.

Shipley WU, Zietman AL, Hanks GE, Coen JJ, Caplan RJ, Won M et al. Treatment related sequelae following external beam radiation for prostate cancer: a review with an update in patients with stages T1 and T2 tumor. J Urol 1994; 152 (Part 2): 1799–1805.

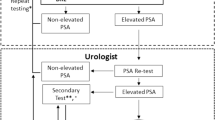

Labrie F, Dupont A, Suburu R, Cusan L, Gomez JL, Koutsilieris M et al. Optimized strategy for detection of early stage, curable prostate cancer: role of prescreening with prostate-specific antigen. Clin Invest Med 1993; 16: 425–439.

Fradet Y, Saad F, Aprikian A, Dessureault J, Elhilali M, Trudel C et al. uPM3, a new molecular urine test for the detection of prostate cancer. Urology 2004; 64: 311–315.

Shigeno K, Igawa M, Shiina H, Kishi H, Urakami S . Transrectal colour Doppler ultrasonography for quantifying angiogenesis in prostate cancer. BJU Int 2003; 91: 223–226.

Chang SS, Reuter VE, Heston WD, Bander NH, Grauer LS, Gaudin PB . Five different anti-prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) antibodies confirm PSMA expression in tumor-associated neovasculature. Cancer Res 1999; 59: 3192–3198.

Reiter RE, Gu Z, Watabe T, Thomas G, Szigeti K, Davis E et al. Prostate stem cell antigen: a cell surface marker overexpressed in prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998; 95: 1735–1740.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Constantinou, J., Feneley, M. PSA testing: an evolving relationship with prostate cancer screening. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 9, 6–13 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.pcan.4500838

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.pcan.4500838

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Advances in stem cell research for the treatment of primary hypogonadism

Nature Reviews Urology (2021)

-

Sarcosine as a marker in prostate cancer progression: a rapid and simple method for its quantification in human urine by solid-phase microextraction–gas chromatography–triple quadrupole mass spectrometry

Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry (2011)

-

Stellenwert von Biomarkern in der Urologie

Der Urologe (2010)

-

Does educational printed material manage to change compliance with prostate cancer screening?

World Journal of Urology (2008)