Abstract

A common assumption is that breeding in polygnous systems is not limited by the number of males because one male can inseminate many females1,2. But here we show that reproductive collapse in the critically endangered saiga antelope (Saiga tatarica tatarica) is likely to have been caused by a catastrophic drop in the number of adult males in this harem-breeding ungulate, probably due to selective poaching for their horns. Fecundity and calf survival are known to be affected by markedly skewed sex ratios3, but in the saiga antelope the sex ratio has become so distorted as to lead to a drastic decline in the number of pregnancies — a finding that has implications both for the conservation of the species and for understanding the reproductive ecology of polygynous ungulates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

S. tatarica tatarica (Fig. 1Footnote 1) is a nomadic inhabitant of the semi-arid rangelands of central Asia and the pre-Caspian. Horns are borne by males and are highly valued in traditional Chinese medicine, which has led to heavy poaching since the demise of the Soviet Union, when the Chinese–Soviet border was opened. Although there was a marked reduction in the proportion of adult males in the population, fecundity remained high, as was expected for a polygynous ungulate4.

Male saiga antelopes have been so ruthlessly hunted that their breeding and populations have been severely disrupted.*

Poaching on both sexes increased as the collapse of the rural economy led to local demand for meat5, but the sex ratio remained heavily biased towards females. From 1998, saiga populations fell markedly throughout their range, with an average annual rate of decline of 46% (ref. 6). By 2002, the global population was only 50,000 individuals, just 5% of its size 10 years previously7, leading to a Critically Endangered listing on the 2002 IUCN Red List and listing on Appendix II of the Convention on Migratory Species.

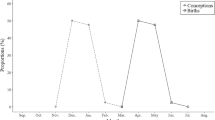

We collected data on saiga population dynamics in Kalmykia, Russia, over the period 1992–2002. Our data set included the number of in utero fetuses in a sample of heavily pregnant females shot during the months of February in the years 1993–2001. During this period, the population size declined rapidly, as did the number of adult males in the population; there was a sudden drop in fecundity in 2001 (Fig. 2a).

a, Proportion of adult (blue diamonds) and juvenile (under 1 year old; triangles) females that were fecund in each year from 1993 to 2001; means are indicated by red diamonds. A mean of 69 females (range, 24–103) was sampled each year. b, Relationship between the proportion of adult males in rutting herds in the months of December during the years 1992–2000, and female fecundity the following spring, fitted as a Gompertz regression; the fit explains 96.2% of the variance. The proportion of younger males and adult females also explained over 90% of the variance in fecundity, which is not surprising as these are proportional values. None of the other potential covariates tested gave a satisfactory fit.

Changes in fecundity rates in Kalmykia were not related to population density or climatic variables, unlike in Kazakhstan8. The best predictor of female fecundity was the proportion of adult males in the population during the previous year's rut, which explained 96.2% of the variance in fecundity (Fig. 2b). Given that 2001 is a clear outlier and the sample size is small, there is uncertainty attached to this result; however, we could not undertake further analyses as the collection of fecundity data has now ceased for conservation reasons.

The most parsimonious explanation for the drop in fecundity in 2001 is a lack of adult males in the population during the rut. This seems to be a threshold effect, operating at a proportion of adult males in the population between 0.025 (1 adult male per 36 females) and 0.009 (1 adult male per 106 females; Fig. 2b).

The proportion of adult males normally seen in unselectively hunted populations is 0.20–0.25 (ref. 9). The lowest proportions of adult males previously recorded in three other populations were 0.023, 0.077 and 0.053, respectively, in 1992–93, just after sex-biased poaching began9, although saiga fecundity remained high in 1993–94 (ref. 4). This supports our inference that the threshold proportion of adult males for reproductive collapse lies below 0.025.

Anecdotal observations of S. tatarica tatarica in the 2000 rut point to a complete reversal in reproductive behaviour. Normally, an adult male defends a harem of 12–30 females9,10. In 2000, however, single males were surrounded by large numbers of females, and dominant females were seen to be aggressively excluding subdominant females from the males: this presumably explains the failure of most first-year females to conceive.

Notes

* The photographer Pavel Sorokin is credited for Fig. 1 of Milner-Gulland et al. (Nature 422, 135; 2003), having been accidentally omitted from the printed Brief Communication.

References

Bergerud, A. T. in The Behaviour of Ungulates and its Relation to Management (eds Geist, V. & Walter, F.) 395–435 (Int. Union Conserv. Nature, Morgues, Switzerland, 1974).

Haigh, J. R. & Hudson, R. J. Farming Wapiti and Red Deer (MosbyYear, St Louis, Missouri, 1993).

Mysterud, A., Coulson, T. N. & Stenseth, N. C. J. Anim. Ecol. 71, 907–915 (2002).

Milner-Gulland, E. J., Bekenov, A. B. & Grachev, I. A. Nature 377, 488–489 (1995).

Robinson, S. Pastoralism and Land Degradation in Kazakhstan. Thesis, Univ. Warwick (2000).

Milner-Gulland, E. J. et al. Oryx 35, 340–345 (2001).

Sharp, R. Oryx 36, 323 (2002).

Coulson, T. N., Milner-Gulland, E. J. & Clutton-Brock, T. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 267, 1771–1779 (2000).

Bekenov, A. B., Grachev, I. A. & Milner-Gulland, E. J. Mamm. Rev. 28, 1–52 (1998).

Sokolov, V. E. & Zhirnov, L. V. (eds) The Saiga: Phylogeny, Systematics, Ecology, Conservation and Use (Russian Acad. Sci., Moscow, 1998; in Russian).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Milner-Gulland, E., Bukreeva, O., Coulson, T. et al. Reproductive collapse in saiga antelope harems. Nature 422, 135 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/422135a

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/422135a

This article is cited by

-

Post-whaling shift in mating tactics in male humpback whales

Communications Biology (2023)

-

Exposure to risk factors experienced during migration is not associated with recent Vermivora warbler population trends

Landscape Ecology (2023)

-

Hunting alters viral transmission and evolution in a large carnivore

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2022)

-

Make flying-fox hunting sustainable again: Comparing expected demographic effectiveness and hunters’ acceptance of more restrictive regulations

Ambio (2022)

-

Hunting strategies to increase detection of chronic wasting disease in cervids

Nature Communications (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.