Abstract

In our study1 we did not address the impact of predicted climate change on malaria incidence because a complete global assessment is reported elsewhere2. Regarding the climate surfaces we used, the data set has superior spatial resolution compared with other data sets of similar temporal extent3,4, and has been used to quantify climate change across Africa at 0.5 × 0.5° spatial resolution5 (although the resulting maps are smoothed to emphasize regional changes). It is inconsistent to assert that these same data are insufficient to demonstrate a lack of climate change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Hay et al. reply

Furthermore, these smoothed patterns5 are at odds with the marked and variable trends in temperature identified across east Africa using long-term temperature records from meteorological stations6. Events occurring at the 0.5 × 0.5° resolution will be less variable when averaged over wider areas, but we know of no evidence that climate surfaces interpolated from meteorological stations consistently fail to reveal trends in climate experienced at those locations.

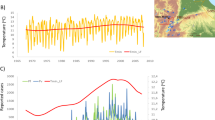

Crucially, further work has confirmed a very high degree of correspondence between the climate surfaces3,4 and meteorological-station data from Kericho. Moreover, these station data show no significant trend in temperature or rainfall during the 1966–95 period over which complete longitudinal hospital records show malaria incidence to have increased significantly7.

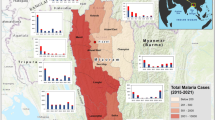

The malaria resurgences documented at these four sites are not "point-prevalence rates", but estimates from longitudinal records of health facilities, whose catchment populations range over continuous highland areas that are similar in size to a pixel of the climate surface that we used3,4.

The sparse coverage of meteorological stations in the data set3,4 before 1910 in the east African region is problematic4, and these data were excluded from our analyses. The full 1901–95 data set was used by one of the correspondents, however, in their trend analyses of African climate5. Moreover, our conclusions remain unaltered in the light of tests repeated for the 1970–95 period, which is coincident with the malaria resurgences and represents the most consistent meteorological-station coverage.

Patz et al. estimate a temperature deviation of 3 °C arising from the difference in the mean elevation of the climate surface pixels3,4 and the elevation of meteorological station sites that contribute to them. However, the thin-plate spline procedure8 used to generate the 1961–90 climate normals3 that formed the basis of the entire climate data set4 explicitly takes account of altitude to correct for the elevational dependency of temperature.

Application of our methodology1 to the regional time-series cited by Patz et al. shows that the purported warming trend is not significant (details available from the authors). It is critical to test for climate changes that coincide in both space and time with the disease data7,9, so changes on regional scales or at distant sites (such as Kakamega and Nairobi) are irrelevant, whether or not they achieve significance.

The more subtle impacts of non-significant long-term changes in climate on malaria incidence deserve to be investigated, but have not been demonstrated, so we cannot attribute significant increases in malaria incidence to non-significant changes in climate. It is because malaria incidence is related to climate that any study of long-term climate change must factor out seasonality, unlike the cited study on seasonal variability over four years10. Finally, windowed Fourier analysis of the meteorological station data for Kericho also showed no change in annual temperature or rainfall variability since 1966 (ref. 11), a conclusion that is corroborated by global-scale analysis of climate variability during this century12.

Rather than climate change, variations in environmental, social and epidemiological factors are more plausible explanations for the malaria resurgences at the four sites we examined1 and at three others in Ethiopia, Madagascar and Tanzania13. Evidence against the epidemiological significance of climate change in the recent malaria resurgences in Africa is mounting7,9,13 and remains unmatched by any contrary evidence.

References

Hay, S. I. et al. Nature 415, 905–909 (2002).

Rogers, D. J. & Randolph, S. E. Science 289, 1763–1766 (2000).

New, M., Hulme, M. & Jones, P. J. Clim. 12, 829–857 (1999).

New, M., Hulme, M. & Jones, P. J. Clim. 13, 2217–2238 (2000).

Hulme, M., Doherty, R., Ngara, T., New, M. & Lister, D. Clim. Res. 17, 145–168 (2001).

King'uyu, S. M., Ogallo, L. A. & Anyamba, E. K. J. Clim. 13, 2876–2886 (2000).

Shanks, G. D., Hay, S. I., Stern, D. I., Biomndo, K. & Snow, R. W. Emerging Infect. Dis. 8, 1404–1408 (2002).

Hutchinson, M. F. Int. J. Georg. Inf. Syst. 9, 385–403 (1995).

Hay, S. I. et al. Direct. Sci. 1, 82–85 (2002).

Githeko, A. & Ndegwa, W. Global Change Hum. Health 2, 54–63 (2001).

Rogers, D. J., Randolph, S. E., Snow, R. W. & Hay, S. I. Nature 415, 710–715 (2002).

Vinnikov, K. Y. & Robock, A. Geophys. Res. Lett. 29, 10.1029/2001GL014025 (2002).

Hay, S. I. et al. Trends Parasitol. (in the press).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hay, S., Cox, J., Rogers, D. et al. Regional warming and malaria resurgence. Nature 420, 628 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/420628a

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/420628a

This article is cited by

-

Drivers of autochthonous and imported malaria in Spain and their relationship with meteorological variables

Euro-Mediterranean Journal for Environmental Integration (2021)

-

The potential effects of climate change on malaria transmission in Africa using bias-corrected regionalised climate projections and a simple malaria seasonality model

Climatic Change (2013)

-

Spatial modelling of the potential temperature-dependent transmission of vector-associated diseases in the face of climate change: main results and recommendations from a pilot study in Lower Saxony (Germany)

Parasitology Research (2008)

-

A changed climate in Africa?

Nature (2004)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.