Abstract

Hagfish and lampreys are unusual for modern vertebrates in that they have no jaws and their skeletons are neither calcified nor strengthened by collagen — the cartilaginous elements of their endoskeleton are composed of huge, clumped chondrocytes (cartilage cells). We have discovered that the cartilage in a 370-million-year-old jawless fish, Euphanerops longaevus, was extensively calcified, even though its cellular organization was similar to the non-mineralized type found in lampreys. The calcification of this early lamprey-type cartilage differs from that seen in modern jawed vertebrates, and may represent a parallel evolutionary move towards a mineralized endoskeleton.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

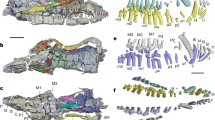

E. longaevus is an anaspid 'ostracoderm' (one of an ensemble of jawless fish aged 470–370 Myr) from the Late Devonian locality of Miguasha, Canada (Fig. 1). Although the endoskeleton of anaspids was previously thought not to have been calcified, that of large, recently discovered specimens of Euphanerops shows extensive calcification. All endoskeletal elements of these specimens show the same, foam-like aspect and are made up of minute, hollow, spherical bodies that are loosely attached either by their walls or by an intervening matrix (Fig. 2a). Thin sections reveal that these spherical bodies are sometimes divided into two chambers, and that their walls are composed of calcified cartilage with evidence of growth rings.

a, Euphanerops displays large, rounded spaces for inclusion of chondrocytes, which are lined with calicified cartilage. b, Lamprey chondrocyte spaces in groups of two or four ('cell nests'), as in Euphanerops. c, Lamprey cartilage calcified in vitro, showing the same calcification pattern as in Euphanerops. Images in b and c are reproduced from ref. 4. CN, cell nest; CS, chondrocyte space; IM, intervening matrix; TM, territorial matrix. Scale bars, 50 µm.

This structure is strikingly similar to that of lamprey cartilage, in which large chondrocyte cells, often in groups of two or four (cell 'nests'1), are surrounded by a 'territorial' matrix with concentric rings that give rise to differential staining (Fig. 2b). In lamprey cartilage that is artificially calcified in vitro, calcium phosphate is deposited first in the territorial matrix (black dots in Fig. 2c) and then in the intervening matrix2, generating the same pattern as is found in Euphanerops.

It is likely that the spherical bodies in Euphanerops contained chondrocytes, surrounded by calcified territorial matrix and held together loosely by a less-calcified intervening matrix. This process of calcification also occurs in the early stages of development of the higher jawed vertebrates (gnathostomes), but it must have occurred later in life in Euphanerops.

Ostracoderms are thought to be more closely related to gnathostomes than to either lampreys or hagfish3,4, but our discovery suggests that the cartilage of Euphanerops was structurally similar to that of lampreys, and that it may also have been non-collagenous. This does not necessarily imply a close relationship between anaspids and lampreys, as has been proposed5. There is no evidence that the calcification pattern that is found in Euphanerops, and which can be imposed in vitro on lamprey cartilage, is a precursor of the large-scale, globular calcification of cartilage and bone that is seen in more derived ostracoderms and in gnathostomes, although it may represent a parallel –– but less successful — move towards developing a calcified endoskeleton.

References

Robson, P., Wright, G. M., Youson, J. H. & Keeley, F. W. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 118B, 71–78 (1997).

Langille, R. M. & Hall, B. K. Acta Zool. 74, 31–41 (1993).

Janvier, P. Palaeontology 39, 259–287 (1996).

Donoghue, P. C. J., Forey, P. L. & Aldridge, R. J. Biol. Rev. 75, 191–251 (2000).

Janvier, P. Early Vertebrates (Clarendon, Oxford, 1996).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Janvier, P., Arsenault, M. Calcification of early vertebrate cartilage. Nature 417, 609 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/417609a

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/417609a

This article is cited by

-

Evolutionary origin of endochondral ossification: the transdifferentiation hypothesis

Development Genes and Evolution (2017)

-

Identification of vertebra-like elements and their possible differentiation from sclerotomes in the hagfish

Nature Communications (2011)

-

Lamprey-like gills in a gnathostome-related Devonian jawless vertebrate

Nature (2006)

-

A lamprey from the Devonian period of South Africa

Nature (2006)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.