Abstract

For more than 100 years, the scientific and educational communities have thought that age is critical to the outcome of language learning1,2, but whether the onset and type of language experienced during early life affects the ability to learn language is unknown. Here we show that deaf and hearing individuals exposed to language in infancy perform comparably well in learning a new language later in life, whereas deaf individuals with little language experience in early life perform poorly, regardless of whether the early language was signed or spoken and whether the later language was spoken or signed. These findings show that language-learning ability is determined by the onset of language experience during early brain development, independent of the specific form of the experience.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The ability to learn language, whether spoken or signed, declines with age3,4,5,6. How the onset and type of the initial language experience contributes to this critical-period phenomenon is unclear. This question cannot be investigated by studying hearing individuals only, because the factors of age and experience are inseparable in these individuals — all hearing babies experience language from birth. But the question can be investigated by studying individuals who were born deaf, because they often do not experience any language until they are enrolled in special programmes7,8. We therefore compared the language-learning capacities of deaf and hearing individuals as a function of early language experience.

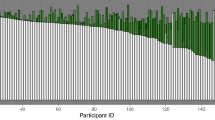

We first investigated whether early experience of a spoken language could facilitate subsequent learning of a signed language. We tested two groups of adults who had learned American Sign Language (ASL) at school between the matched ages of 9 and 15 years and who had used it for over two decades. One group (n = 9) was born hearing, had experienced spoken English in early life, and had later learned ASL after becoming profoundly deaf (≥ 90 decibels) as a result of viral infection; the second group (n = 9) was born profoundly deaf and had had little experience of language before being exposed to ASL in school (auditory speech-perception abilities were at chance levels even with hearing aids). Deaf adults who had little experience of language in early life showed low levels of ASL performance; in contrast, late-deafened adults showed high levels of ASL performance (Fig. 1; paired t = 4.17; d.f., 8; P < 0.001).

a, American Sign Language (ASL) performance of deaf adults who had experienced no language in early life, and of deaf adults who had experienced spoken language in early life. Subjects were tested using a task requiring recall of complex ASL sentences. b, English performance of deaf adults who had had no experience of language in early life, of deaf adults who had experienced ASL in infancy, and of hearing adults who had experienced a spoken language other than English in infancy. Subjects were tested using a task requiring judgements of whether complex English sentences given in print were grammatically correct; chance performance is 50%. Further details are available from the authors.

We next investigated whether early experience of a signed language facilitates subsequent learning of a spoken language. We tested three groups of adults who had learned English in school at comparable ages between 4 and 13 years and who had used it for over 12 years. One group (n = 14) was born profoundly deaf and had had little language experience before being exposed to ASL in school; the second group (n = 13) was born profoundly deaf and had experienced ASL in infancy; the third group (n = 13) was born hearing and had experienced various spoken languages in infancy (Urdu, French, German, Italian or Greek). Deaf and hearing adults who had experienced either a signed or a spoken language in early life showed similarly high levels of performance on the later learned language, English, whereas deaf adults who had little experience of language in early life showed low levels of performance (Fig. 1; F2,37 = 11.32, P < 0.0001).

Our results show that the ability to learn language arises from a synergy between early brain development and language experience, and is seriously compromised when language is not experienced during early life. This is consistent with current knowledge about how experience affects visual development in animals9 and humans10, and about learning and brain development in animals11,12. The timing of the initial language experience during human development strongly influences the capacity to learn language throughout life, regardless of the sensorimotor form of the early experience.

References

Colombo, J. Psychol. Bull. 91, 260–275 (1982).

Lenneberg, E. Biological Foundations of Language (Wiley, New York, 1967).

Johnson, J. & Newport, E. Cogn. Psychol. 21, 60–69 (1989).

Newport, E. Cogn. Sci. 14, 11–28 (1990).

Mayberry, R. I. & Eichen, E. J. Mem. Lang. 30, 486–512 (1991).

Emmorey, K., Bellugi, U., Friederici, A. & Horn, P. Appl. Psycholing. 16, 1–23 (1995).

Mayberry, R. I. J. Speech Hearing Res. 36, 51–68 (1993).

Mayberry, R. I. in Child Neuropsychology (eds Segalowitz, S. J. & Rapin, I.) (Elsevier, Amsterdam, in the press).

Wiesel, T. N. Nature 299, 583–591 (1982).

Goldberg, M. C., Maurer, D., Lewis, T. L. & Brent, H. P. Dev. Neuropsychol. 19, 55–81 (2001).

Greenough, W. T. & Black, J. E. in Developmental Behavioral Neuroscience (eds Gunna, M. R. & Nelson, C. A.) 155–200 (Erlbaum, Hillsdale, New Jersey, 1992).

Kolb, B., Forgie, M., Gibb, R., Gorny, G. & Rowntree, S. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 22, 143–159 (1998).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mayberry, R., Lock, E. & Kazmi, H. Linguistic ability and early language exposure. Nature 417, 38 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/417038a

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/417038a

This article is cited by

-

On the nature of role shift

Natural Language & Linguistic Theory (2023)

-

Cognitive functioning in Deaf children using Cochlear implants

BMC Pediatrics (2021)

-

Enhancing the NICU language environment with a neonatal Cuddler program

Journal of Perinatology (2021)

-

Functional and structural brain connectivity in congenital deafness

Brain Structure and Function (2021)

-

How Bilingualism Contributes to Healthy Development in Deaf Children: A Public Health Perspective

Maternal and Child Health Journal (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.