Abstract

The existence of a papillary lesion of the urinary bladder with a benign clinical course and recognizable morphologic features that merit the benign categorization “papilloma” has been controversial. The clinical aspects and histologic features of these lesions remain to be fully elucidated. We have studied the clinicopathologic features of 26 patients with urothelial papillomas and correlated them with outcome. Papillomas occurred in two distinct clinical settings: (1) de novo neoplasms (23/26) or (2) those occurring in patients with a known clinical history of bladder cancer (“secondary” papillomas; 3/26). Follow-up information was available in 14/23 of the de novo cases (mean = 39 mo) and in 3/3 secondary cases (mean = 24 mo). Patients with de novo papillomas had a mean age of 46 years; 16 were male and 7 were female. Twelve of 14 had a benign clinical course with no recurrences; 1 developed a recurrent papilloma at 3 years, and 1 developed a pT3a high-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma at 4 years. Patients with secondary papillomas had a mean age of 66 years; two were male and one was a female. One of these patients developed two additional recurrences, and two patients had no new recurrences. Morphologically, the papillary architecture ranged from a common simple, nonhierarchical arrangement to, infrequently, more complex anastomosing papillae with budding. The individual papillae ranged from small (most common), with scant stroma and slender fibrovascular cores, to large, with marked stromal edema and/or cystitis cystica-like urothelial invaginations. Common to all was a lining of normal-appearing urothelium without hyperplasia, maintenance of normal polarity, and frequent prominence of the umbrella cell layer. Overall, no patient with a diagnosis of papilloma died of disease; only one patient with a de novo lesion (7.0%) had a recurrent papilloma, and 1/14 (7.0%) progressed to a higher grade and stage of disease, although this patient was on immunosuppressive therapy secondary to a renal transplant. De novo urothelial papillomas occur in younger patients and usually have a benign course. Urothelial papillomas are histologically and probably biologically distinctive tumors and merit distinction from other higher risk papillary neoplasms of the urinary bladder.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The term papilloma in the urinary bladder has been used differently by different authors, such that there is controversy whether a benign lesion truly exists in the spectrum of urothelial neoplasms. Historical aspects of this issue were reviewed in detail by Eble and Young in 1989 and will not be repeated here (1). Since the time of that review, the existence of typical papillomas, as defined by the 1973 WHO classification (2), has been acknowledged by the inclusion of this diagnostic category in the consensus classification of urinary bladder neoplasms by the World Health Organization and the International Society of Urologic Pathologists (WHO/ISUP) (3). Despite its acknowledged existence by those interested in this area, detailed studies of the lesion are few, particularly when it is remembered that most of the papers having the word “papilloma” in their title in the older literature are recording cases that would be low-grade papillary carcinoma (Grade I transitional cell carcinoma) using the 1973 WHO classification (2) or would be papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential using the most recent scheme (WHO/ISUP, 1998) (3). The rarity of papillomas, when strictly defined, also results in any one observer having limited experience, because even large institutions often have no more than one case per year. By collecting cases from two large institutions and adding in cases seen in consultation, we have identified a relatively large series of cases that we have diagnosed as papilloma. In this study, which is based on conventional morphology, we present our findings of an investigation of the histopathologic features of this entity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The surgical pathology files of The Emory Hospital and the James Homer Wright Laboratory of the Department of Pathology at The Massachusetts General Hospital, as well as the consultation files of two of the authors (MBA and RHY) were searched for urothelial papillomas as defined by the 1998 WHO/ISUP (3) and the 1973 WHO (2) classification systems. All available slides (1–4 slides) were reviewed, and the diagnosis of papilloma was confirmed by all three authors. Tumors were evaluated with respect to the architectural arrangement of the papillae (relative size of papillae, shape, complexity, and presence of endophytic growth), the contents of the fibrovascular cores, the number of cell layers in the urothelium, the character of the umbrella cell layer, the polarity of the urothelium to the basement membrane, the mitotic activity, and the nuclear cytology. Clinical information and follow-up data were obtained by reading the surgical pathology reports, reviewing patient charts, and contacting treating urologists. The clinical data obtained included the patient age and sex, location of the tumor, size of the tumor, the presence or absence of multifocality, disease recurrence or progression (grade and/or stage), duration of the follow-up period, status of disease at last follow-up, and the treatment regimen. A recurrence was defined as a new occurrence of a papilloma anywhere within the urinary bladder ≥3 months after the initial diagnosis. Progression was defined as a new occurrence of a bladder neoplasm with a higher grade and/or stage ≥3 months after the initial diagnostic procedure.

RESULTS

Clinical Features

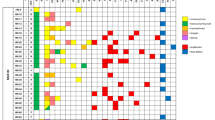

The clinical data is summarized in Table 1. Papillomas occurred in two distinct clinical settings: (1) de novo neoplasms (23/26) or (2) secondary papillomas, those occurring in patients with a known past clinical history of bladder neoplasia or a concurrent urothelial lesion (3/26).

Follow-up information for a period of >10 months was available in 14 of 23 de novo cases (range = 11–120 mo; mean = 39 mo; median = 28 mo). Patients with de novo papillomas had a mean age of 46 years (range = 8–76 y; median = 41 y). There was a 2:1 male predominance. Twelve of the 14 patients had a benign clinical course with no recurrences. One patient developed a pT3a high-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma 4 years after the initial diagnosis of a papilloma. This patient had a typical papilloma with small slender papillae and a normal urothelial lining; however, he was on immunosuppressive therapy secondary to a renal transplant and had a history of chronic rejection. One other patient had a recurrent papilloma at 3 years follow-up. Three patients diagnosed with papillomas had prior histories of bladder neoplasia or had a concomitant neoplasm of a higher grade (one with history of papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential/grade I transitional cell carcinoma, one with a history of low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma/grade II transitional cell carcinoma, and one with both concomitant carcinoma in situ and a papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential). The patients with secondary papillomas had a mean age of 66 years (range, 55–73 y; median = 71 y). Two of the patients were male, and one patient was a female. The patient with a history of a low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma/Grade II transitional cell carcinoma had two additional recurrences but no grade or stage progression. The two other patients had no new recurrences and were clinically free of disease at last follow-up.

Cystoscopic Findings

Of the 23 de novo papillomas, four were reportedly multifocal. The tumors ranged in size from 0.2 to 2.8 cm in greatest diameter (mean = 0.76 cm). The location of the tumor was available in 12 cases: 5-posterior, 4-lateral, 2-trigone, and 1-dome.

Light-Microscopic Findings

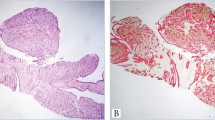

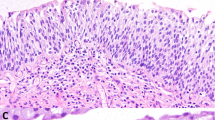

All cases had a well-formed papillary architecture with fibrovascular cores. The papillary architecture ranged from a common simple, nonhierarchical arrangement in 19/26 (73%) cases (Fig. 1) to more complex anastomosing papillae with budding in 7/26 (27%) cases (Fig. 2, A and B). The individual papillae ranged from small (19/26) with scant stroma and slender fibrovascular cores (Fig. 1) to large with marked stromal edema (7/26; Fig. 3). Urothelial invaginations (endophytic growth) into the papillary cores were present in 11 of 26 (42%) cases (Fig. 4, A–B). Common to all cases was a lining of normal-appearing urothelium without hyperplasia (the urothelium ranged from four to seven cells in thickness). The urothelium was oriented perpendicular to the basement membrane with recapitulation of normal histology including basal cells, intermediate cells, and umbrella cells in most cases (Figs. 2B, 5A). In 16 cases the superficial umbrella cell layer was conspicuously prominent with increased cytoplasm, often with vacuolization (Fig. 5, A–B). The nuclear morphology in 23/26 cases was bland without any nuclear atypia and had the appearance of normal urothelium. Three cases had degenerative-type nuclear atypia that was usually focal, but otherwise the cases had typical features of urothelial papilloma (Fig. 6). Rare mitotic figures were identifiable in only 2/26 cases; none were atypical mitoses.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we have presented our findings on the morphologic features of a series of exophytic bladder lesions that we have diagnosed as urothelial papilloma. We believe that a variety of morphologic features enables them to be distinguished from the low-grade neoplasm that has been most recently characterized as papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential (WHO/ISUP 1998) (3), most of which would have been designated as Grade I papillary transitional cell carcinoma using the older 1973 WHO approach (2).

Although the recognition of a papilloma rests entirely on light-microscopic observations, it is worth emphasizing at the outset that our experience suggests a very definite tendency for this lesion to occur in young patients (only 5 of 23 patients were >50 years of age) and to be solitary in the majority of cases. Although there are both architectural and cytologic differences between papillomas and papillary neoplasms of low malignant potential, in our experience, architectural ones are dominant in the separation of the two lesions. We acknowledge that there will inevitably be some cases in which there may be some morphologic overlap; however, the papillae in cases of papilloma characteristically are shorter than those of papillary urothelial neoplasms of low malignant potential, are not covered by urothelium that is hyperplastic, and, on average, have a greater covering of umbrella cells that is often quite prominent. Additionally, the urothelium at the base of papillomas in our series did not show the urothelial hyperplasia characteristically seen at the base and/or lateral to the stalk of papillary urothelial neoplasms of low malignant potential. One can rarely encounter foci in papillary neoplasms of low malignant potential/Grade I transitional cell carcinoma in which the morphology is similar, if not identical to urothelial papilloma. By convention, these neoplasms are graded according to the highest histologic grade present. A few of our papillomas showed a mild degree of cytologic atypia that at first made us reluctant to accept these cases, but when we studied them in comparison to our entire series of cases, the overall features were more characteristic of the papilloma category. We felt that the cytologic atypia may well be degenerative in nature, and because it was not associated with mitotic activity, this did not in and of itself warrant classification as a papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential.

Although the focus of this study was the distinction of papillomas from urothelial neoplasms of low malignant potential/Grade I transitional cell carcinoma, our results also demonstrate that there is some overlap between the typical (exophytic) papilloma and the well-known endophytic lesion referred to as inverted papilloma, a finding that has been stressed in previous writings (3, 4). Several of our typical papillomas had a component with an inverted growth pattern sometimes reminiscent of florid cystitis cystica. Cases in which the exophytic and endophytic components are essentially equal in prominence may warrant the diagnosis of mixed typical and inverted urothelial papilloma.

When one suspects a diagnosis of papilloma, one differential diagnostic consideration is papillary urothelial hyperplasia, a lesion thought to be a putative precursor of low-grade papillary urothelial neoplasms (5). In contrast to papillomas, however, they generally have a hyperplastic urothelium (more than seven cells in thickness) with an undulating pattern consisting of thin mucosal papillary folds of varying heights. It is important to note that the discrete fibrovascular cores are lacking and that the vascularity is concentrated at the base of the urothelial proliferation. Papillary urothelial hyperplasia shares a benign, normal-appearing cytology of the proliferating urothelium in common with urothelial papillomas, but, given the hyperplastic urothelium, is probably a closer mimic of papillary urothelial neoplasms of low malignant potential/Grade I transitional cell carcinoma.

As noted in the introduction to this article, the older literature contains many reports under the designation “papilloma” of the urinary bladder, but the vast majority of these cannot adequately be analyzed and compared with our series because they clearly use that designation for the lesion that would now be classified as papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential according to current approaches. There is only one sizable study of papillomas of the urinary bladder that has been published since the 1998 WHO/ISUP classification (6). Of the 52 patients with urothelial papillomas that were studied, 4 patients developed recurrent papillomas, and 1 other patient developed a papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential. Those investigators concluded that papillomas have a low incidence of recurrence and rarely, if ever, develop urothelial carcinoma. Although that study thoroughly documented the clinical course of patients with papillomas, it did not discuss in detail their morphologic spectrum.

It is noteworthy that three of our patients had a concomitant bladder neoplasm of higher grade. This is obviously a greater frequency than would be expected in the population at large and could be used to cast doubt on our categorization of the papillomas as unequivocally benign. However, we believe this association cannot be used as a strong argument against categorization of a papilloma as defined by us herein as benign. The mere existence of a papilloma obviously represents some proliferative tendency of the urothelium, and we do believe that patients with papilloma should receive some degree of circumspect clinical follow-up. This does highlight that there is a small group of “secondary” papillomas occurring in older patients with a history of or concomitant urothelial neoplasm in which the prognosis is predicted by the higher-grade lesion. Similar observations hold true in urothelial carcinoma in situ, which, when primary or de novo, has different progression rates than that of those with secondary carcinoma in situ (7). Our one patient with a de novo papilloma who progressed in grade and stage was a renal transplant patient on immunosuppressive therapy. It is difficult to draw any conclusions from this case but the predilection of immunocompromised patients to develop malignancies at an accelerated rate is known.

Very limited studies have investigated the immunohistochemical profile of urothelial papillomas; cytokeratin 20 (CK20) has been analyzed in two studies (8, 9), and standard isoform CD44 antibodies in one study (8). The findings corroborate the morphologic observation of normal-appearing urothelium on a fibrovascular stalk. The staining pattern with CK20 in urothelial papillomas in most cases is similar to that seen in normal urothelium (i.e., CK20 immunoreactivity is restricted to the umbrella cell layer with an absence of staining in the basal and intermediate cells) (8, 9). CD44 expression in urothelial papillomas, like normal urothelium, is limited to the basal cell layer (8). In contrast, papillary urothelial neoplasms of low malignant potential and low-grade papillary transitional cell carcinomas show higher rates of CK20 and CD44 overexpression (8). In our opinion, however, immunohistochemistry plays no role in the diagnosis of urothelial papillomas, which is essentially based on light microscopy using architectural and cytologic features.

Recently, it has been suggested that papillary urothelial hyperplasia is a clonal process (10). Chow et al. (10) have reported that both papillary urothelial hyperplasia and urothelial neoplasms of low malignant potential/Grade I papillary transitional cell carcinomas share a loss of heterozygosity and/or microsatellite instability, whereas no urothelial papillomas tested showed any genetic alterations. Chow et al. argue that papillary urothelial hyperplasia may be a precursor lesion that has the potential to progress to papillary transitional cell carcinoma, but urothelial papillomas seem to represent a distinct bladder lesion. These preliminary molecular data further support the distinction of papillomas from papillary urothelial neoplasms of low malignant potential.

Although it is difficult to compare clinical outcomes in a small series, urothelial papillomas are morphologically distinct bladder neoplasms and, given their reported immunohistochemical and molecular differences, merit distinction from papillary urothelial neoplasms of low malignant potential. Patients with de novo papillomas are generally younger and typically have a favorable clinical course.Table 2

References

Eble JN, Young RH . Benign and low-grade papillary lesions of the urinary bladder: a review of the papilloma-papillary carcinoma controversy, and a report of five typical papillomas. Semin Diagn Pathol 1989; 6: 351–371.

Mostofi FK, Sobin LH, Torloni H . Histologic typing of urinary bladder tumors. International histological classification of tumors. No. 10. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1973.

Epstein JI, Amin MB, Reuter VR, Mostofi FK, and the Bladder Consensus Conference Committee. The World Health Organization/International Society of Urological Pathology consensus classification of urothelial (transitional cell) neoplasms of the urinary bladder. Bladder Consensus Conference Committee. Am J Surg Pathol 1998; 22: 1435–1448.

Kunze E, Schauer A, Schmitt M . Histology and histogenesis of two different types of inverted papillomas. Cancer 1983; 51: 348–358.

Taylor DC, Bhagavan BS, Larsen MP, Cox JA, Epstein JI . Papillary urothelial hyperplasia. A precursor to papillary neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol 1996; 20: 1481–1488.

Cheng L, Darson M, Cheville JC, et al. Urothelial papilloma of the bladder. Clinical and biologic implications. Cancer 1999; 86: 2098–2101.

Orozco RE, Martin AA, Murphy WM . Carcinoma in situ of the urinary bladder. Clues to host involvement in human carcinogenesis. Cancer 1994; 74: 115–122.

Desai S, Lim SD, Jimenez RE, et al. Relationship of cytokeratin 20 and CD44 protein expression with WHO/ISUP grade in pTa and pT1 papillary urothelial neoplasia. Mod Pathol 2000; 13: 1315–1323.

Harnden P, Mahmood N, Southgate J . Expression of cytokeratin 20 redefines urothelial papillomas of the bladder. Lancet 1999; 353: 974–977.

Chow N, Cairns P, Eisenberger CF, et al. Papillary urothelial hyperplasia is a clonal precursor to papillary transitional cell bladder cancer. Int J Cancer 2000; 89: 514.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McKenney, J., Amin, M. & Young, R. Urothelial (Transitional Cell) Papilloma of the Urinary Bladder: A Clinicopathologic Study of 26 Cases. Mod Pathol 16, 623–629 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MP.0000073973.74228.1E

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MP.0000073973.74228.1E