Abstract

The K-ras oncogene is activated in approximately 90% of pancreatic adenocarcinomas, and the DPC4 (MADH4/SMAD4) tumor suppressor gene is inactivated in approximately 55% of pancreatic adenocarcinomas. The contributions of these genetic alterations to the development of adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of Vater have not been fully established. One hundred forty surgically resected ampullary adenocarcinomas (76 with associated adenomas with high-grade dysplasia) were immunohistochemically labeled for the DPC4 gene product, and in 85 cases the results were correlated with the status of the K-ras oncogene from previously reported data. The results were correlated with clinical outcome and with other pathologic predictors of prognosis. Complete loss of Dpc4 labeling was identified in 34% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 26%, 43%) of the invasive carcinomas and in none (upper 95% CI: 6%) of the associated adenomas. Focal loss of Dpc4 was seen in three (4%; 95% CI: 1%, 14%) of the areas of high-grade dysplasia. Complete loss of Dpc4 expression was seen in 28/77 intestinal-type tumors, in 17/46 pancreaticobiliary-type tumors, and in 0/10 colloid carcinomas. Activating point mutations in the K-ras gene were identified in 40% of the invasive cancers. There was no correlation between K-ras gene mutations and Dpc4 expression and no correlation between these variables and survival. The overall 5-year survival rate was 38%. Lymph node metastases were associated with shorter survival (P = .03). Loss of Dpc4 expression occurs in approximately one third of invasive ampullary cancers but is not seen in adenomas; thus, loss of Dpc4 expression occurs late in ampullary carcinogenesis. Although ampullary and pancreatic adenocarcinomas share histologic and molecular features, ampullary carcinomas are less likely to show loss of Dpc4 expression or K-ras gene mutations.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The ampulla of Vater lies at the confluence of the pancreatic and biliary ducts. Ampullary epithelial neoplasms may have either pancreaticobiliary or intestinal-type morphology. Ninety percent of ampullary epithelial tumors are malignant (1, 2), and many arise from adenoma precursors. The invasive component of these neoplasms often disrupts the normal anatomy of the ampulla, making subtyping of ampullary carcinomas based on exact site of origin difficult.

Ampullary carcinomas represent approximately 10% of cancers resected via the Whipple procedure (pancreaticoduodenectomy) (3). The peak age incidence is in the 8th decade, with men more commonly affected than women (1). The 5-year survival of patients with resected ampullary carcinoma is approximately 33–38% (4, 5), significantly better than the 10–20% 5-year survival rate of patients with resected pancreatic ductal carcinoma (6, 7, 8, 9) Although some of this survival difference can be explained by earlier presentation and resectability of ampullary carcinomas, even ampullary carcinomas with lymph node metastases are associated with better survival than are node-negative pancreatic carcinomas (4), and patients with Stage I ampullary carcinoma tend to survive longer than do patients with Stage I pancreatic carcinoma (10). These data suggest that ampullary carcinomas are biologically different from pancreatic carcinomas.

DPC4 (MADH4, SMAD4), a tumor-suppressor gene located at 18q21.1, has been shown to mediate the effects of TGF-β superfamily signaling, resulting in downstream growth inhibition (11, 12). The DPC4 gene is inactivated in approximately 55% of pancreatic adenocarcinomas (13). Mutations in DPC4 also have been identified in other tumor types, including bladder (12–35%), lung (24–65%), prostate (19–45%), and ovarian (27–67%) carcinomas, as previously reviewed (14). Loss of Dpc4 has been shown in 10% of proximal and 55% of distal bile duct carcinomas (15). Immunohistochemical labeling for the DPC4 gene product (Dpc4) has been shown to mirror the DPC4 genetic status of pancreatic adenocarcinomas, with complete loss of staining corresponding to genetic inactivation of the DPC4 gene (16, 17).

Mutations in the K-ras oncogene have been detected in approximately 75–95% of pancreatic adenocarcinomas (18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28) and in approximately 38% of ampullary carcinomas (4, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36). K-ras gene mutations also have been demonstrated in ampullary adenomas, even in areas of low-grade dysplasia. Additionally, there is a strong correlation (93%) between the K-ras gene mutations found in ampullary adenomas and their associated infiltrating carcinomas (29, 30). These data suggest that K-ras gene mutations in ampullary carcinomas, when present, occur early in ampullary tumorigenesis.

The purpose of the present study was to define the role of Dpc4 inactivation and correlate it with K-ras gene status in a large series of well-characterized ampullary neoplasms.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Specimen Selection

Patients undergoing partial pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple resections) or total pancreatectomy for carcinomas of the ampulla of Vater between the years of 1970 and 2000 were collected from the files of Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH; n = 80) and Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC; n = 85). Clinical and pathological data were obtained from the patients’ medical records and the surgical pathology files of JHH and MSKCC. These variables included age, gender, race, pathologic tumor stage, nodal or distant metastases, and survival.

Immunohistochemistry

The hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides from each of the 165 cases were screened by light microscopy, and sections having invasive ampullary carcinoma, associated adenoma with high-grade dysplasia (if present), and adjacent normal duodenum and pancreas (if possible) were selected for immunolabeling. Paraffin blocks were available from 140 of these cases. Unstained 4-μm sections were then cut from selected paraffin blocks and deparaffinized by routine techniques. Next, slides were treated with 1× sodium citrate buffer (diluted from 10× heat-induced epitope retrieval buffer; Ventana-Bio Tek Solutions, Tucson, AZ) before steaming for 20 minutes and then incubating with a 1:100 dilution of monoclonal antibody to Dpc4 protein (clone B8, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Finally, anti-Dpc4 antibody was detected by adding secondary antibody, followed by avidin-biotin complex and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine chromagen. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. A section of each selected block was processed identically with omission of the primary antibody to serve as a negative control.

Histologic Evaluation

Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections from each case were reviewed for histologic grade (using accepted criteria [4], histologic type, and the presence of adenoma with or without high-grade dysplasia. Histologic types were recorded as “intestinal,” “pancreaticobiliary,” “colloid,” and “other” (4). Intestinal-type tumors were composed of tall columnar, gland-forming epithelium with pseudostratified nuclei similar to adenocarcinomas of the large or small intestine. Pancreaticobiliary tumors were composed of low cuboidal epithelium similar to the case with adenocarcinomas of the common bile duct and pancreas. Colloid carcinomas were composed of nests of glandular epithelium surrounded by pools of mucin, similar to mucinous carcinomas of the breast, colon, and pancreas. At least 50% of the invasive carcinoma was mucinous in those tumors categorized as colloid carcinomas (4). Tumors with “other” histology included solid, sarcomatoid, papillary, and adenosquamous patterns, with the diagnoses based on published criteria (4).

In 140 cases, immunohistochemical labeling of Dpc4 was evaluated by four of the authors (DMM, PA, RHH, and DSK) at a multiheaded microscope, with agreement by consensus in all cases examined. The immunolabeling pattern of each carcinoma was scored as positive or negative (17). Neoplasms scored as positive showed, in general, both nuclear and cytoplasmic labeling of the neoplastic epithelium. However, neoplasms with only nuclear Dpc4 labeling were also scored as positive. Neoplasms without detectable nuclear Dpc4 labeling were scored as negative. The adenomatous component of the neoplasm with high-grade dysplasia, if present, was also scored as positive or negative. Normal duodenum, pancreatic ducts, islets of Langerhans, pancreatic acini, lymphocytes, and stromal fibroblasts, all of which had moderate expression of the DPC4 gene product, served as a positive internal control in each of the sections.

K-ras Gene Analysis

The sequence of the K-ras oncogene had been previously determined in 85 of the cases (31). These findings were correlated with the clinical and pathological findings.

Statistical Analysis

The major statistical endpoint of this study was survival. Event time distributions for this endpoint were estimated using the method of Kaplan and Meier (37) and compared using the log-rank statistic (38) or the proportional hazards regression model (39). Factors tested for prognostic value included age at diagnosis, gender, Dpc4 labeling, race, nodal status, histology, grade, tumor diameter, stage, and K-ras gene mutations. In proportional hazards regression models, most variables were entered as categorical effects, and the hazard ratios for these factors reflect either their presence or their absence. Age was entered as a continuous effect, and the relative hazard reflects the risk of death per unit change in the value of the factor (age).

Factors associated with Dpc4 labeling were selected based on cross tabulations and logistic regression modeling. For statistical simplification, Dpc4 labeling was classified as negative and positive, with negative nuclear labeling considered negative. Cross tabulations were analyzed using χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests where appropriate. Logistic regression models (40) were used to determine the effects of multiple factors on Dpc4 labeling. Histology and K-ras gene mutations were also tested for associations with primary tumor stage (pT1 and pT2 versus pT3 and pT4) and with nodal status through logistic regression models and χ2 analysis.

All P values reported are two-sided. Computations were performed using the Statistical Analysis System (41) or EGRET (42).

RESULTS

Clinicopathological Characteristics

Clinicopathologic characteristics of available data for the 165 patients with ampullary carcinomas are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 65.5 ± 12.1 years, including 90 men and 74 women; in five cases, the age was not available. Sixty-two tumors (86%) occurred in white patients, but data on the patients’ race was available for only 72 cases.

Tumor Histology and Stage

Of the infiltrating carcinomas, 10/165 (6%) were well differentiated, 107/165 (65%) were moderately differentiated, and 48/165 (29%) were poorly differentiated. An associated ampullary adenoma with high-grade dysplasia was identified in 73 of 156 cases (47%). In 9 cases, we could not clearly distinguish between an adenoma with high-grade dysplasia and overgrowth of the epithelium by well-differentiated infiltrating carcinoma. The most common histologic type was intestinal (94/165, 57%), followed by pancreaticobiliary (51/165, 31%) and colloid (12/165, 7% (4). These types are illustrated in Figure 1A—C. Eight carcinomas had “other” histology (as described above).

Infiltrating ampullary adenocarcinoma and associated adenomas with high-grade dysplasia. A, infiltrating intestinal-type ampullary adenocarcinoma with negative Dpc4 labeling and adjacent stroma showing normal Dpc4 labeling. B, infiltrating pancreaticobiliary ampullary adenocarcinoma with negative Dpc4 labeling and adjacent normal duodenal crypts. C, infiltrating colloid-type adenocarcinoma with strong Dpc4 labeling. D, adenoma with high-grade dysplasia labeling for Dpc4 (arrow) with distinct Dpc4-positive (right side) and Dpc4-negative (left side) infiltrating carcinoma.

The most frequent tumor (T) stage at resection was pT3 (67/161, 42%), followed by pT2 (63/161, 39%) and pT1 (23/161, 14%). Only 8/161 patients had pT4 tumors (5%). Tumor stage was not recorded in three patients. Metastases to resected lymph nodes were identified in 87/164 (53%) patients. Lymph node status was not recorded in one case. The pancreaticobiliary type tended to be associated with more advanced tumor stage (pT3 and pT4), compared with colloid carcinoma (Table 2); however, this difference was not statistically significant (odds ratio, 3.1; 95% CI, 0.82–11.67; P = .09). Additionally, the pancreaticobiliary type was associated with an increased risk of lymph node metastasis at the time of resection (odds ratio, 3.35; 95% CI, 1.60–7.02; P = .001), compared with intestinal cases (Table 3).

Dpc4 Expression

Thirty-four percent of the invasive ampullary carcinomas showed complete loss of Dpc4 labeling, whereas all of the associated adenomas with high-grade dysplasia labeled for Dpc4. In many cases, Dpc4-positive adenomas were seen superficial to Dpc4-negative infiltrating carcinomas. Focal loss of Dpc4 labeling was seen in 3/73 (4%) adenomas with high-grade dysplasia and in 7 infiltrating carcinomas (Fig. 1D). Thirty-six percent of intestinal and 37% of pancreaticobiliary patterns showed loss of labeling for Dpc4 (Fig. 1A–C; P, n.s.), although carcinomas with colloid histology always labeled for Dpc4. Complete loss of Dpc4 expression was seen in 2 of 7 (29%) of carcinomas with “other” histology. One case with “other” histology was considered uninterpretable. Dpc4 labeling was not associated with tumor type, differentiation, lymph node status, or tumor stage.

Correlation of Dpc4 Expression with K-Ras Gene Analysis

As reported previously, activating point mutations in the K-ras gene were identified in 33 (39%) of the 85 analyzed invasive cancers. The most common mutation in infiltrating carcinomas was substitution of aspartate for glycine at codon 12 (14%), followed by valine at codon 12 (9%), aspartate at codon 13 (5%), cysteine at codon 12 (4%), arginine at codon 12 (4%), alanine at codon 12 (2%), and serine at codon 12 (1%). In this study, neoplasms with K-ras gene mutations tended to be higher staged (odds ratio, 2.38; P = .06), with lymph node metastases (odds ratio, 1.51; P = .36), but these differences were not significant (31). K-ras gene status did not correlate with Dpc4 labeling (P = .39).

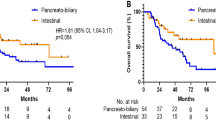

Correlation of Histologic Type, Dpc4 and K-ras Status, and Survival

The 5-year survival rate for patients with resected ampullary carcinoma was 38%, with a median survival of 48 months. Of the clinicopathologic parameters analyzed, only lymph node metastases were associated with significantly shorter survival at 5 years (hazard ratio = 1.69; 95% CI = 1.05–2.70; P = .029; Fig. 2). Histologic type did not correlate with survival, nor did primary tumor (T) stage, Dpc4 labeling, or K-ras gene status.

DISCUSSION

Carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater is distinguished from conventional pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma clinically and pathologically, but the relationship of these tumor types at the genetic level is still being investigated. The majority of ampullary carcinomas have intestinal-type histology, reflecting the contribution of the intestinal epithelium of the papilla to the ampullary lining. Other cases more resemble primary carcinomas of the pancreas and bile ducts and have a pancreaticobiliary type histology. Ampullary carcinoma is less aggressive than pancreatic carcinoma, with lower rates of lymph node metastases and a higher 5-year survival rate (43).

This study demonstrates an overall 5-year survival rate (after resection) of 38%, similar to the case in previous reports (4). Among clinicopathologic parameters, survival was affected only by lymph node status. The relationship between survival and lymph node metastasis has been reported previously in ampullary adenocarcinomas (5, 31)

Loss of Dpc4 expression was seen in 34% of invasive ampullary carcinomas, a finding similar to that in a report published elsewhere (44). This rate of DPC4 loss is lower than that seen in invasive pancreatic carcinomas (55%) (13) but higher than that found in colorectal carcinoma (45). Complete loss of Dpc4 was seen only in invasive ampullary carcinoma, implying that in some cases, DPC4 mutations are implicated in the process of tumor invasion and may represent a late genetic alteration in tumorigenesis. This model of DPC4 mutation as a late-stage event in tumorigenesis recently has been proposed in pancreatic carcinoma (16). However, in pancreatic carcinoma, the late-stage precursor lesions (PanIN3) already often show Dpc4 loss.

K-ras gene mutations are less common in invasive ampullary carcinomas (40%) compared with in invasive pancreatic carcinomas (75–95%) (18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28). The rate of K-ras gene mutation in ampullary carcinoma is similar to that found in colorectal carcinoma, as is the frequency of different specific mutations (1, 31, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49). Previously published data showed a high correlation between mutation in ampullary adenomas and in their adjacent infiltrating tumors, suggesting that K-ras gene mutations occur relatively early in carcinogenesis (31). We were unable to demonstrate a relationship between K-ras mutation and Dpc4 expression in ampullary carcinomas.

The histologic similarity of some ampullary carcinomas (pancreaticobiliary type) to primary tumors of the pancreas raises the possibility that this subset of ampullary carcinomas may be more closely related to pancreatic (or bile duct) carcinomas. However, the failure of Dpc4 expression or K-ras gene status (31) to correlate with the histologic type of ampullary carcinoma does not support the possibility of a closer genetic relationship between pancreaticobiliary type ampullary carcinomas and primary tumors of the pancreas or distal bile duct.

The difference in genotype between ampullary and pancreatic adenocarcinomas may account for some of the observed differences in behavior. Other genetic differences may certainly account for some of this difference as well. Imai and colleagues (50) found that 77.8% of ampullary carcinomas have mutations in the TGF-β-receptor-II gene (which involves the same pathway as Dpc4). Achille and colleagues (51) showed that microsatellite instability in ampullary tumors was associated with a comparatively good prognosis. This latter group of investigators also showed that mutations in the APC and K-ras genes were present at early stages (adenomas) of ampullary tumors, whereas p53 gene inactivation was associated with progression to malignancy (52). As APC mutations are not seen in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (53) and in light of the findings in DPC4 and K-ras presented here, those data add credence to the concept that ampullary carcinomas have some significant genetic differences from pancreatic cancers.

Many previous studies have been performed on small numbers of cases, reflecting the relatively infrequency of ampullary carcinomas. Given the potential for surgical cure in ampullary tumors identified at early stages, a rigorous examination of the biological characteristics of the tumors may prove instructive and aid our understanding of tumorigenesis in the region.

References

Baczako K, Buchler M, Beger HG, Kirkpatrick CJ, Haferkamp O . Morphogenesis and possible precursor lesions of invasive carcinoma of the papilla of Vater: epithelial dysplasia and adenoma. Hum Pathol 1985; 16: 305–310.

Blackman E, Nash SV . Diagnosis of duodenal and ampullary epithelial neoplasms by endoscopic biopsy: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study. Hum Pathol 1985; 16: 901–910.

Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Sohn TA, Lillemoe KD, Pitt HA, Talamini MA, et al. Six hundred fifty consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies in the 1990s: pathology, complications, and outcomes. Ann Surg 1997; 226: 248–257.

Albores-Saavedra J, Henson DE, Klimstra D . Tumors of the gallbladder, extrahepatic bile ducts, and ampulla of Vater: atlas of tumor pathology. 3rd series ed. Washington, D.C.: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 2000.

Talamini MA, Moesinger RC, Pitt HA, Sohn TA, Hruban RH, Lillemoe KD, et al. Adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of Vater. A 28-year experience. Ann Surg 1997; 225: 590–599.

Sohn TA, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Koniaris L, Kaushal S, Abrams RA, et al. Resected adenocarcinoma of the pancreas—616 patients: results, outcomes, and prognostic indicators. J Gastrointest Surg 2000; 4: 567–579.

Benassai G, Mastrorilli M, Quarto G, Cappiello A, Giani U, Forestieri P, et al. Factors influencing survival after resection for ductal adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas. J Surg Oncol 2000; 73: 212–218.

Mosca F, Giulianotti PC, Balestracci T, Di Candio G, Pietrabissa A, Sbrana F, et al. Long-term survival in pancreatic cancer: pylorus-preserving versus Whipple pancreatoduodenectomy. Surgery 1997; 122: 553–566.

Conlon KC, Klimstra DS, Brennan MF . Long-term survival after curative resection for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clinicopathologic analysis of 5-year survivors. Ann Surg 1996; 223: 273–279.

Bakkevold KE, Kambestad B . Long-term survival following radical and palliative treatment of patients with carcinoma of the pancreas and papilla of Vater-the prognostic factors influencing the long-term results. A prospective multicentre study. Eur J Surg Oncol 1993; 19: 147–161.

Dai JL, Turnacioglu KK, Schutte M, Sugar AY, Kern SE . Dpc4 transcriptional activation and dysfunction in cancer cells. Cancer Res 1998; 58: 4592–4597.

de Winter JP, Roelen BA, ten Dijke P, van der Burg B, van den Eijnden-van Raaij AJ . DPC4 (SMAD4) mediates transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGF-beta1) induced growth inhibition and transcriptional response in breast tumour cells. Oncogene 1997; 14: 1891–1899.

Hahn SA, Schutte M, Hoque ATMS, Moskaluk CA, daCosta LT, Rozenblum E, et al. DPC4, a candidate tumor suppressor gene at human chromosome 18q21.1. Science 1996; 271: 350–353.

Schutte M, Hruban RH, Hedrick L, Cho KR, Nadasdy GM, Weinstein CL, et al. DPC4 gene in various tumor types. Cancer Res 1996; 56: 2527–2530.

Argani P, Shaukat A, Kaushal M, Wilentz RE, Su GH, Sohn TA, et al. Differing rates of loss of DPC4 expression and of p53 overexpression among carcinomas of the proximal and distal bile ducts. Cancer 2001; 91: 1332–1341.

Wilentz RE, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Argani P, McCarthy DM, Parsons JL, Yeo CJ, et al. Loss of expression of Dpc4 in pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia: evidence that DPC4 inactivation occurs late in neoplastic progression. Cancer Res 2000; 60: 2002–2006.

Wilentz RE, Su GH, Dai JL, Sparks AB, Argani P, Sohn TA, et al. Immunohistochemical labeling for Dpc4 mirrors genetic status in pancreatic carcinoma: a new marker of DPC4 inactivation. Am J Pathol 2000; 156: 37–43.

Almoguera C, Shibata D, Forrester K, Martin J, Arnheim N, Perucho M . Most human carcinomas of the exocrine pancreas contain mutant c- K-ras genes. Cell 1988; 53: 549–554.

Smit VT, Boot AJM, Smits AMM, Fleuren GJ, Cornelisse CJ, Bos JL . K-ras codon 12 mutations occur very frequently in pancreatic adenocarcinomas. Nucleic Acids Res 1988; 16: 7773–7782.

Motojima K, Urano T, Nagata Y, Shiku H, Tsurifune T, Kanematsu T . Detection of point mutations in the Kirsten-ras oncogene provides evidence for the multicentricity of pancreatic carcinoma. Ann Surg 1993; 217: 138–143.

Hruban RH, van Mansfeld ADM, Offerhaus GJA, van Weering DHJ, Allison DC, Goodman SN, et al. K-ras oncogene activation in adenocarcinoma of the human pancreas. A study of 82 carcinomas using a combination of mutant-enriched polymerase chain reaction analysis and allele-specific oligonucleotide hybridization. Am J Pathol 1993; 143: 545–554.

Pellegata NS, Sessa F, Renault B, Bonato MS, Leone BE, Solcia E, et al. K-ras and p53 gene mutations in pancreatic cancer: ductal and nonductal tumors progress through different genetic lesions. Cancer Res 1994; 54: 1556–1560.

Grunewald K, Lyons J, Frohlich A, Feichtinger H, Weger RA, Schwab G, et al. High frequency of Ki-ras codon 12 mutations in pancreatic adenocarcinomas. Int J Cancer 1989; 43: 1037–1041.

Tada M, Ohashi M, Shiratori Y, Okudaira T, Komatsu Y, Kawabe T, et al. Analysis of K-ras gene mutation in hyperplastic duct cells of the pancreas without pancreatic disease. Gastroenterology 1996; 110: 227–231.

Scarpa A, Capelli P, Villanueva A, Zamboni G, Lluìs F, Accolla R, et al. Pancreatic cancer in Europe: Ki-ras gene mutation pattern shows geographical differences. Int J Cancer 1994; 57: 167–171.

Berrozpe G, Schaeffer J, Peinado MA, Real FX, Perucho M . Comparative analysis of mutations in the p53 and K-ras genes in pancreatic cancer. Int J Cancer 1994; 58: 185–191.

Hruban RH, van Mansfeld AD, Offerhaus GJ, van Weering DH, Allison DC, Goodman SN, et al. K-ras oncogene activation in adenocarcinoma of the human pancreas. A study of 82 carcinomas using a combination of mutant-enriched polymerase chain reaction analysis and allele-specific oligonucleotide hybridization. Am J Pathol 1993; 143: 545–554.

Dergham ST, Dugan MC, Kucway R, Du W, Kamarauskiene DS, Vaitkevicius VK, et al. Prevalence and clinical significance of combined K-ras mutation and p53 aberration in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Int J Pancreatol 1997; 21: 127–143.

Chung CH, Wilentz RE, Polak MM, Ramsoekh TB, Noorduyn LA, Gouma DJ, et al. Clinical significance of K-ras oncogene activation in ampullary neoplasms. J Clin Pathol 1996; 49: 460–464.

Gallinger S, Vivona AA, Odze RD, Mitri A, O’Beirne CP, Berk TC, et al. Somatic APC and K-ras codon 12 mutations in periampullary adenomas and carcinomas from familial adenomatous polyposis patients. Oncogene 1995; 10: 1875–1878.

Howe JR, Klimstra DS, Cordon-Cardo C, Paty PB, Park PY, Brennan MF . K-ras mutation in adenomas and carcinomas of the ampulla of Vater. Clin Cancer Res 1997; 3: 129–133.

Malats N, Porta M, Pinol JL, Corominas JM, Rifa J, Real FX . Ki-ras mutations as a prognostic factor in extrahepatic bile system cancer. PANK-ras I Project Investigators. J Clin Oncol 1995; 13: 1679–1686.

Motojima K, Tsunoda T, Kanematsu T, Nagata Y, Urano T, Shiku H . Distinguishing pancreatic carcinoma from other periampullary carcinomas by analysis of mutations in the Kirsten-ras oncogene. Ann Surg 1991; 214: 657–662.

Scarpa A, Zamboni G, Achille A, Capelli P, Bogina G, Iacono C, et al. ras-family gene mutations in neoplasia of the ampulla of Vater. Int J Cancer 1994; 59: 39–42.

Stork P, Loda M, Bosari S, Wiley B, Poppenhusen K, Wolfe H . Detection of K-ras mutations in pancreatic and hepatic neoplasms by non-isotopic mismatched polymerase chain reaction. Oncogene 1991; 6: 857–862.

Watanabe M, Asaka M, Tanaka J, Kurosawa M, Kasai M, Miyazaki T . Point mutation of K-ras gene codon 12 in biliary tract tumors. Gastroenterology 1994; 107: 1147–1153.

Kaplan EL, Meier P . Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc 1958; 53: 457–480.

Mantel N, Haenszel W . Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst 1959; 22: 719–748.

Cox DR . Regression models and life tables (with discussion). J R Stat Soc 1972; 34: 187–220.

Cox DR . The analysis of binary data. London: Methuen; 1970.

SAS Institute. SAS user’s guide: statistics. 5th ed. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 1985.

Statistics and Epidemiology Research Corporation. EGRET user’s manual. Seattle, WA: Statistics and Epidemiology Research Corporation; 1988.

Yeo CJ, Sohn TA, Cameron JL, Hruban RH, Lillemoe KD, Pitt HA . Periampullary adenocarcinoma: analysis of 5-year survivors. Ann Surg 1998; 227: 821–831.

Moore PS, Orlandini S, Zamboni G, Capelli, Rigaud G, Falconi M, et al. Pancreatic tumors: molecular pathways implicated in ductal cancer are involved in ampullary but not in exocrine nonductal or endocrine tumorigenesis. Br J Cancer 2001; 84: 253–262.

Thiagalingam S, Lengauer C, Leach FS, Schutte M, Hahn SA, Overhauser J, et al. Evaluation of candidate tumor suppressor genes on chromosome 18 in colorectal cancers. Nat Genet 1996; 13(3): 343–346.

Forrester K, Almoguera C, Han K, Grizzle WE, Perucho M . Detection of high incidence of K-ras oncogenes during human colon tumorigenesis. Nature 1997; 327: 298–303.

Finkelstein SD, Sayegh R, Christensen S, Swalsky PA . Genotypic classification of colorectal adenocarcinoma. Biologic behavior correlates with K-ras-2 mutation type. Cancer 1993; 71: 3827–3838.

Breivik J, Meling GI, Spurkland A, Rognum TO, Gaudernack G . K-ras mutation in colorectal cancer: relations to patient age, sex and tumour location. Br J Cancer 1994; 69: 367–371.

Vogelstein B, Fearon ER, Hamilton SR, Kern SE, Preisinger AC, Leppert M, et al. Genetic alterations during colorectal-tumor development. N Engl J Med 1988; 319: 525–532.

Imai Y, Tsurutani N, Oda H, Inoue T, Ishikawa T . Genetic instability and mutation of the TGF-beta-receptor-II gene in ampullary carcinomas. Int J Cancer 1998; 76: 407–411.

Achille A, Biasi MO, Zamboni G, Bogina G, Iacono C, Talamini G, et al. Cancers of the papilla of Vater: mutator phenotype is associated with good prognosis. Clin Cancer Res 1997; 3: 1841–1847.

Achille A, Scupoli MT, Magalini AR, Zamboni G, Romanelli MG, Orlandini S, et al. APC gene mutations and allelic losses in sporadic ampullary tumours: evidence of genetic difference from tumours associated with familial adenomatous polyposis. Int J Cancer 1996; 68: 305–312.

Seymour AB, Hruban RH, Redston M, Caldas C, Powell SM, Kinzler KW, et al. Allelotype of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res 1994; 54: 2761–2764.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McCarthy, D., Hruban, R., Argani, P. et al. Role of the DPC4 Tumor Suppressor Gene in Adenocarcinoma of the Ampulla of Vater: Analysis of 140 Cases. Mod Pathol 16, 272–278 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MP.0000057246.03448.26

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MP.0000057246.03448.26

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Molecular Aberrations in Periampullary Carcinoma

Indian Journal of Surgical Oncology (2017)

-

Distribution and pathological features of pancreatic, ampullary, biliary and duodenal cancers resected with pancreaticoduodenectomy

World Journal of Surgical Oncology (2015)

-

Tumoren der Papilla Vateri

Der Pathologe (2012)

-

Clinicopathologic Analysis of Ampullary Neoplasms in 450 Patients: Implications for Surgical Strategy and Long-Term Prognosis

Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery (2010)

-

Molecular Analysis of PIK3CA, BRAF, and RAS Oncogenes in Periampullary and Ampullary Adenomas and Carcinomas

Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery (2009)