Abstract

Two cases of cartilaginous differentiation of the peritoneum not associated with an intraabdominal malignancy are described. This is the first detailed report of cartilaginous metaplasia of the peritoneum. The patients were female, ages 53 (Patient 1) and 77 years (Patient 2). Prior medical histories were significant for a culdotomy (to drain pelvic abscesses associated with pelvic inflammatory disease) in Patient 1 and for an open abdominal surgery in Patient 2. The peritoneal lesions were incidental findings in both cases. In Patient 1, surgery was performed for a septated ovarian cyst; the other patient underwent surgery to relieve obstructive bowel symptoms. In Patient 1, multiple firm, white lesions ranging from 2.0 to 7.0 mm were present on the serosal surfaces and the mesenteries of the small and large bowel. In Patient 2, a single firm, white lesion measuring 2 cm in maximum dimension was removed from the mesentery of the ileum. Microscopically, the lesions consisted of small nodules of mature hyaline cartilage surrounded by nondescript fibrous tissue and covered by mesothelium. There was no foreign body giant cell reaction, inflammation, or other reactive changes in the surrounding adipose tissue. These may represent metaplastic lesions of the secondary mullerian system, or a unique peritoneal response to previous surgical manipulation. Alternatively, these may represent benign neoplastic lesions (chondroma) of the submesothelium.

Similar content being viewed by others

REPORT OF CASES

Case 1

Patient 1 was a 53-year old Caucasian female who presented with complaints of low back discomfort. She gave a medical history of self-induced abortion at 6 months’ gestation, complicated by pelvic inflammatory disease and pelvic abscesses, approximately 30 years before presentation. Those abscesses reportedly were drained through a culdotomy, although the specific details were unavailable for review. An ultrasound at current presentation revealed a septated right ovarian mass. At surgery, several firm, white nodules ranging from 2 to 7 mm were noted throughout the peritoneal cavity and were excised from several locations along the serosal surfaces and mesenteries of the small and large bowel. The patient underwent a total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and has had no recurrence of pleural, peritoneal, or gynecologic diseases after a 9-year follow-up.

Case 2

Patient 2 was a 77-year-old Caucasian female who presented with abdominal distention, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. She gave a medical history of a total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy approximately 28 years before presentation for pelvic pain caused by uterine leiomyomata. Radiographic studies revealed an obstruction in the small bowel. During an exploratory laparotomy, a single firm, white nodule measuring 2.0 cm in maximum dimension was identified and excised from the mesentery of the ileum, just lateral of midline. There were significant adhesions involving the small and large bowel that were lysed. The last recorded follow-up was 1 year after presentation, at which time there had been no development of any peritoneal or pleural diseases.

PATHOLOGIC FINDINGS

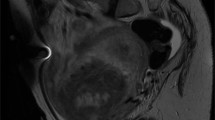

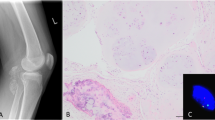

Macroscopically, the peritoneal nodules from Case 1 consisted of several firm, glistening, white tissue fragments ranging from 2 to 7 mm. The left ovary measured 10.0 × 8.5 × 6.0 cm and was replaced by a unilocular cyst filled with clear fluid. The internal lining was smooth and without papillae. No lesions were identified in the uterus, fallopian tubes, or right ovary. The specimen from Case 2 consisted of a single firm, glistening, white tissue fragment measuring 2.0 cm in maximum dimension. The central portions were yellow and gritty. The specimens from both cases were processed routinely for microscopic examination. Microscopically, Case 1 consisted of lobulated nodules of perichondrium-lined mature hyaline cartilage that were surrounded by adipose tissue and overlined by benign mesothelium (Fig. 1). The left ovary was replaced by a serous cystadenoma. Sections obtained from the uterus showed weakly proliferative endometrium and adenomyosis. A focus of endometriosis was identified in the left fallopian tube; the cervix and the right adnexa showed no pathologic changes. The nodule from Case 2 had a microscopic appearance similar to Case 1, but in addition displayed calcific rimming of some individual chondrocytes in the central portions (Fig. 2). Neither case had any associated inflammation, fat necrosis, or foreign-body giant cell reaction in the surrounding fibrous and adipose tissue.

DISCUSSION

Non-mesothelioma–associated cartilaginous differentiation of the human peritoneal tissues has never been fully described in the literature to the best of the authors’ knowledge, although a single case is cited in a surgical pathology text (1). That case was interpreted as a probable metaplastic lesion of the submesothelium. Although osseous and/or cartilaginous differentiation in pleural malignant mesotheliomas have been described in several reports (2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8), Kiyozuka et al. (9) reported the only case of a peritoneal malignant mesothelioma with osseous and cartilaginous differentiation. In animal models (rats), however, Rittinghausen and colleagues (10) were able to induce peritoneal malignant mesotheliomas with cartilaginous and osseous differentiation after intraperitoneal injections of asbestos fibers.

The histogenetic explanation for cartilaginous differentiation in peritoneal tissues has been the source of some controversy. This differentiation has customarily been explained by the theory that there exists a population of submesothelial multipotent cells with ability to differentiate along mesenchymal and mesothelial lines, a concept originally suggested by Klemperer and Rabin in 1932 (11). This was supported by the electron microscopic studies of Raftery (12), who observed the ultrastructure of rat peritoneum after mechanical injury and described a mesenchymal cell that “appeared intermediate in form between primitive mesenchymal cells on one hand and proliferating fibroblasts or mesothelial cells on the other.” The cells eventually differentiated into mesothelium, which covered up the defect. Perhaps the best support for the multipotent cell theory came from the studies of Bolen et al. (13). Using light microscopic, ultrastructural, and immunohistochemical studies, those investigators demonstrated that normal surface mesothelium expressed both low molecular weight cytokeratins (LMWK) and high molecular weight cytokeratins (HMWK), whereas submesothelial cells expressed vimentin only while at rest. However, when reactive, these submesothelial cells displayed a loss of vimentin immunoreactivity and progressively acquired LMWK and HMWK immunoreactivity as the cell differentiated towards the mesothelial surface. Other investigators believe that desquamated mesothelial cells in the peritoneum are the primary source of mesothelial regeneration (14). Donna and Betta (5) thought that the mesothelial cell was not only totipotent but represented real mesoderm that retained the potential to differentiate along embryonic developmental lines, including toward cartilage and bone. Hence, they suggested the term mesodermoma, instead of mesothelioma, to emphasize the mesodermal origin of associated tumors (5).

In the human peritoneum, at least seven well-documented cases of mesenteric heterotopic ossification (or osseous metaplasia) have been reported (15, 16, 17). The fact that 6 of those 7 cases were associated with a history of abdominal surgery underscores the ability of the peritoneal tissues to differentiate into heterologous tissues in response to injury.

Cartilaginous heterotopia has been reported in several organs, including such unlikely sites as the prostate (18), tonsils (19), and thyroid gland (20). In the uterus and cervix, cartilaginous heterotopia is a rare but well-recognized phenomenon. Remmele and colleagues (21) reported two cases and extensively reviewed the literature on the subject. Nodules of cartilage are typically identified in the endometrium, myometrium, and endocervix, and in two cases (22, 23), a cartilaginous nodule was present in the anterior uterine subserosa. In the first patient (22), a bar of cartilage was noted beneath the uterine serosa of a 32-year-old gravida 1, abortus 1 female during a salpingectomy for hydrosalpinx. A similarly located cartilaginous nodule in the anterior uterine subserosa of a second patient, a 36-year-old gravida 17, para 7, abortus 10, was reported by Jakubowitz (23). These cases are similar to our Case 2, who had a single nodule of cartilage on a peritoneal surface. However, in our case, the excised nodule was in the mesentery of the ileum and was not in close proximity to the previous location of the uterus (history of hysterectomy, see report of cases). The possibility of a benign cartilaginous neoplasm (chondroma) also warrants some consideration in these cases. In contrast, the diffuse presence of the cartilaginous lesions in our Case 1 would seem to argue against a neoplastic pathogenesis. The diffuse occurrence of seemingly heterologous tissues in the peritoneum is well recognized when such tissues are smooth muscle (leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata) or glial tissue (gliomatosis peritonei). The latter is of particular interest because some authors have suggested that the glial nodules are implanted into the peritoneum from capsular defects in ovarian teratomas (24), and a similar mechanism might explain the diffuse cartilaginous lesions in Case 1. However, as previously indicated, no teratomatous lesion was identified in either ovary. Given the gynecologic history of self-induced abortion (approximately 30 y before presentation), these lesions may also represent organized products of conception showing cartilaginous differentiation. However, the presence of the nodules in the entire peritoneal cavity and the lack of involvement of the pelvic peritoneum or gynecologic organs argues against that possibility.

We share these cases for the benefit of surgeons who might encounter these lesions and for pathologists who would be making their intraoperative evaluation.

References

Rosai J . Peritoneum, retroperitoneum, and related structures.In: Rosai J, editor. Ackerman’s surgical pathology. 8th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1996.p. 2138–2141.

Goldstein B . Two malignant pleural mesotheliomas with unusual histologic features. Thorax 1979; 34: 375–379.

Yoshii C, Imai S, Hoshino H, Sugaya H, Mizutani Y, Iwaki H, et al. A case of malignant pleural mesothelioma with osseous and cartilaginous formation. Jpn J Thorac Dis 1992; 30: 338–342.

Yousem SA, Hocholzer L . Malignant mesotheliomas with osseous and cartilaginous differentiation. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1987; 111: 62–66.

Donna A, Betta PG . Differentiation towards cartilage and bone in a primary tumor of pleura. Further evidence in support of the concept of mesoderma. Histopathology 1986; 10: 101–108.

McCaughey WTE . Primary tumors of the pleura. J Pathol Bacteriol 1958; 76: 517–529.

Postoloff AV . Mesothelioma of pleura. Arch Pathol 1944; 37: 286–289.

Trotter BB, Palmer WS . Mesenchymatous mesothelioma: report of a case with unusual histological features. Cancer 1959; 12: 884–888.

Kiyozuka Y, Miyazaki H, Yoshizawa K, Senzaki H, Yamamoto D, Inoue K, et al. An autopsy case of malignant mesothelioma with osseous and cartilaginous differentiation: bone morphogenetic protein-2 in mesothelial cells and its tumor. Dig Dis Sci 1999; 44: 1626–1631.

Rittinghausen S, Ernst H, Muhle H, Mohr U . Atypical malignant mesotheliomas with osseous and cartilaginous differentiation after intraperitoneal injection of various types of mineral fibers in rats. Exp Toxicol Pathol 1992; 44: 55–58.

Klemperer P, Rabin CB . Primary neoplasms of the pleura. A report of five cases. Arch Pathol 1931; 11: 385.

Raftery AT . Regeneration of parietal and visceral peritoneum: an electron microscopical study. J Anat 1973; 115: 375–391.

Bolen JW, Hammar SP, McNutt MA . Reactive and neoplastic serosal tissue: a light microscopic, ultrastructural and immunocytochemical study. Am J Surg Pathol 1986; 10: 34–37.

Whitaker D, Manning LS, Robinson DW, Shilkin KB . The pathobiology of mesothelium.In: Henderson DW, Shilkin KB, Landois SL, Whitaker D, editors. Malignant mesothelioma. New York: Hemisphere; 1992.p. 25–56.

Wilson JD, Montague CJ, Salcuni P, Bordi C, Rosai J . Heterotopic mesenteric ossification (“intraabdominal myositis ossificans”): report of five cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1999; 23: 1464–1470.

Lemeshev Y, Lahr CJ, Denton J, Kent SP, Diethelm AG . Heterotopic bone formation associated with intestinal obstruction and small bowel resection. Ala J Med Sci 1983; 20: 314–317.

Yannopoulos K, Katz S, Flesher L, Geller A, Berroya R . Mesenteris ossificans. Am J Gastroenterol 1992; 87: 230–233.

Bedrosian SA, Goldman RL, Sung MA . Heterotopic cartilage in prostate. Urology 1983; 21: 536–537.

Bhargava D, Raman R, Khalfan Al Abri R, Bushnurmath B . Heterotopia of the tonsil. J Laryngol Otol 1996; 110: 611–612.

Finkle HI, Goldman RL . Heterotopic cartilage in the thyroid. Arch Pathol 1973; 95: 48–49.

Remmele W Schmidt-Wontroba, Kaiser E, Piroth H . Heterotopes knorpel-gewebe im uterus: bericht uber zwei falle and literaturubersicht. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 1988; 48: 184–188.

Roth E, Taylor HB . Heterotopic cartilage in the uterus. Obstet Gynecol 1966; 28: 834–844.

Jakubowitz O . Beitrag zur klinik und histologie der adenomyosis (adenomyohyperplasie) uteri interna. Berlin: Inaug Diss; 1925.

Robboy SJ, Scully RE . Ovarian teratoma with glial implants on the peritoneum: an analysis of 12 cases. Hum Pathol 1970; 1: 643–653.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fadare, O., Bifulco, C., Carter, D. et al. Cartilaginous Differentiation in Peritoneal Tissues: A Report of Two Cases and a Review of the Literature. Mod Pathol 15, 777–780 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MP.0000017565.19341.63

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MP.0000017565.19341.63

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Heterotopic chondroid tissue of the main bile duct mimicking Klatskin tumor: case report and review of the literature

Clinical Journal of Gastroenterology (2019)

-

Chondroid nodule in the female peritoneum arises from normal tissue and not from teratoma or conception product

Virchows Archiv (2018)

-

Malignant mesothelioma with heterologous elements: clinicopathological correlation of 27 cases and literature review

Modern Pathology (2008)