Abstract

Proteus syndrome is a rare, sporadic disorder that causes postnatal overgrowth of multiple tissues in a mosaic pattern. Characteristic manifestations include: overgrowth and hypertrophy of limbs and digits, connective tissue nevus, epidermal nevus and hyperostoses. Various benign and malignant tumors and hamartomas may complicate the clinical course of patients with the syndrome. Commonly encountered tumors include hemangiomas, lymphangiomas and lipomas. Tumors of the genital tract occur less often. Bilateral ovarian cystadenomas are regarded as having diagnostic value in Proteus syndrome when occurring within the first two decades of life. We describe a 3-year-old girl with Proteus syndrome who developed bilateral paraovarian villoglandular endometrioid cystadenomatous tumors of borderline malignancy (low malignant potential) of the broad ligament. Desmoplastic tumor implants, presumably noninvasive, were present in biopsies from the pelvic floor, cul-de-sac and omentum. This is the first recognized example of a cystic borderline epithelial tumor of the female genital tract and the first paraovarian tumor reported in a patient with Proteus syndrome. Previously reported tumors and cystic lesions involving the female genital tract and the male genital tract in patients with Proteus syndrome are reviewed. We suspect that specific testicular and paratesticular tumors may prove to have the same diagnostic value in Proteus syndrome as do bilateral cystic ovarian and paraovarian tumors.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Proteus syndrome is a rare and sporadic disorder that causes postnatal overgrowth of multiple tissues in a mosaic pattern (1). More than 120 cases have been reported (2), and only several hundred patients in the United States and western Europe are estimated to be affected with Proteus syndrome (1). The responsible genetic defect has not been identified. The working hypothesis by Happle (3, 4) postulates that Proteus syndrome is caused by a postzygotic mosaic alteration in a gene that is lethal in the nonmosaic state. Patients typically present at an early age with hypertrophy or asymmetry of limbs, and digits. Hyperostoses, various hamartomatous lesions, epidermal nevi, connective tissue tumors, and a characteristic connective tissue nevus may be found. The latter lesion is almost pathognomonic of Proteus syndrome (5). Criteria for the diagnosis and evaluation of Proteus syndrome patients were formulated at a National Institutes of Health (NIH) workshop in 1998 (Table 1) (1, 5).

Various benign and malignant tumors may complicate the clinical course of patients with the syndrome (6, 7). Commonly encountered tumors include lipomas, hemangiomas, and lymphangiomas. Tumors of the genital tract occur less often. Certain neoplasms occurring before the end of the second decade of life, specifically bilateral ovarian cystadenomas or parotid monomorphic adenoma, are regarded as important findings in establishing a diagnosis of Proteus syndrome (1, 5). Herein, we report a 3-year-old patient with Proteus syndrome who developed bilateral paraovarian villoglandular endometrioid cystadenomatous tumors of borderline malignancy (low malignant potential) with peritoneal implants. It is the first recognized borderline cystic epithelial tumor and the first example of a paraovarian tumor reported in Proteus syndrome. She is the eighth reported patient with a cystic lesion of the uterine adnexae in a patient with this rare syndrome. Previously reported tumors and related lesions of the female genital tract and male genital tract in Proteus syndrome are reviewed.

CASE REPORT

The patient, a 3-year-old white girl, was the second born child of a nonconsanguinous marriage of healthy parents (mother 30 and father 52 years of age). The mother had an uneventful prenatal period. The vaginal delivery was spontaneous at 38 weeks of gestation. At birth, all parameters (length, weight, head circumference, Apgar score, Dubowitz maturity scale and development) were within normal limits. A large, flat red birthmark was present on her left leg. Her hands and feet were unremarkable. Her only sibling, a brother, her parents and other immediate family members have no developmental abnormalities.

At about 6 months of age, the parents noticed asymmetrical enlargement of the long and ring digits of both hands (Fig. 1, A–B). Villus pubic hair (Tanner Stage I) was also noted. Between 9 and 13 months of age, she developed bilateral breast enlargement (Tanner Stage II) without vaginal discharge or axillary hair. Serum levels of thyroid stimulating hormone, follicle stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone were normal, as was a gonadotropin releasing hormone stimulation test. The features were regarded as most consistent with premature thelarche. A pelvic ultrasound at 13.5 months showed bilateral ovarian cysts (1.1 cm and 0.5 cm). Following consultation with a pediatric geneticist at age 19 months, a diagnosis of Proteus syndrome was established. Also noted at that time a 2 × 2 cm area of increased subcutaneous tissue in the upper part of the left sole of the foot (a mild form of “moccasin foot”) and slightly increased subcutaneous fat on upper third of the left palm.

At 3 years of age, she experienced an asymptomatic increase in abdominal girth over a 6-month period. Ultrasound examination of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a complex, predominantly cystic 20 cm mass occupying the entire abdomen and pelvis. Doppler showed low resistance arterial flow within the solid components and the septations. Magnet resonance imaging (MRI) showed marked upward and lateral displacement of the kidney and surrounding structures by a large multiloculated mass (Fig. 2). A normal uterus was seen; the ovaries were not identified. Abdominal exploration was performed and revealed bilateral giant cystic masses involving the adnexae (Fig. 3). The masses were paraovarian and did not involve the ovaries, fallopian tubes or the uterus. Exophytic tissue from the tumor surface and two pelvic floor nodules were biopsied and frozen section consultations obtained. Both masses were then resected without sacrificing the ovaries, although the left fallopian tube was not salvageable. Multiple peritoneal and omental biopsies were performed. An incidental finding of intestinal malrotation was managed by standard Ladd procedure and appendectomy. The patient had an uneventful recovery. Follow-up ultrasound 7 months later revealed two normal ovarian structures and no evidence of recurrence of the paraovarian tumors.

RESULTS

Both tumors had similar gross and histologic features. Each consisted of a large multilocular cystic neoplasm (right: 15 × 12 × 8 cm, 809 gm; left: 18 × 17 × 10 cm, 1218 gm) with a cyst wall thickness of 0.2 cm (Fig. 4). Clear brown fluid filled the cysts. Papillary and polypoid tumor protruded into the lumen of the cyst and covered about 10 to 15% of the cyst lining bilaterally. The left-sided tumor also had a small exophytic component on the external surface.

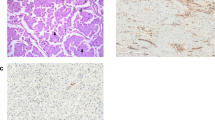

Histologically, both paraovarian neoplasms were similar. Each had a highly complex papillary and villoglandular architecture with an endometrioid pattern of closely spaced branching glands (Figs. 5 and 6). In some areas, there was an almost confluent or labyrinthine pattern. The epithelial cells were very well differentiated with scattered cells having low-grade nuclear atypia (Fig. 7). Mitotic figures were present, but very infrequent. Ciliated cells were prominent in some areas. Destructive stromal invasion of the cyst walls and septa was absent. The tumors were interpreted as a highly proliferative villoglandular variant of an endometrioid (or tuboendometrioid) cystadenomatous tumor of borderline malignancy (or low malignant potential, LMP). In view of the absence of unequivocally malignant nuclear features, a diagnosis of grade 1 intracystic endometrioid adenocarcinoma was not made. Because criteria for cystic borderline endometrioid tumors of the ovary and paraovarian structures have not yet been satisfactorily defined, this distinction admittedly is largely subjective.

Desmoplastic tumor implants were identified in biopsies from the pelvic floor, cul-de-sac and omentum (Fig. 8). Many of these resembled implants of a borderline serous tumor. Some implants contained a few psammoma bodies, and psammoma bodies without demonstrable neoplastic epithelial cells were present in additional pelvic wall biopsies. The left fallopian tube was histologically unremarkable. As part of the diagnostic evaluation of the paraovarian tumors and the exclusion of an endometrioid yolk sac tumor and an epithelioid mesothelioma, numerous immunostains were done. The neoplastic cells were negative for alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAP), calretinin and cytokeratins (CK) 5/6. Stains for CA-125, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and BerEp4 were diffusely positive.

DISCUSSION

The legendary John Carey Merrick, often referred to as “the elephant man” and commonly regarded as a victim of neurofibromatosis type 1, is now believed to have had Proteus syndrome (8). The syndrome was first described by Cohen and Hayden in 1979 who reported a newly recognized disorder in two patients (9). Later, Wiedemann et al. (10) further delineated the syndrome and named it after the Greek god Proteus to denote its variability of clinical expression. Because it is an intrinsically variable disorder, the diagnosis of Proteus syndrome may be difficult. Clinical features overlap with other overgrowth or hamartomatous disorders. Currently, there is no specific molecular marker or diagnostic laboratory test to aid in the diagnosis. Of sixteen patients referred to the NIH for evaluation and study of Proteus syndrome, the diagnosis could be confirmed in only ten cases (5). The other six patients had the Kippel-Trenaunay syndrome or the hemihyperplasia/multiple lipomatosis syndrome. To date, more than 120 cases of Proteus syndrome have now been reported (2).

Various benign and malignant neoplasms may complicate Proteus syndrome (7, 11). In one review, about one-third of the tumors were multiple (11). In several reports, the lesions have been divided into common neoplasms and uncommon neoplasms (6, 11). Included in the common neoplasms are subcutaneous hemangiomas, lymphangiomas and lipomas. Approximately 30 uncommon neoplasms have been described. Some of these, however, were actually cysts and hyperplasias (6), rather than neoplasms. Recently, the non-neoplastic and neoplastic lesions have been listed with the neoplasms as “tumors” (1, 7), a more acceptable but still problematic designation. Most of the uncommon tumors have occurred in the genital tract, central nervous system and parotid gland (6, 7, 11).

A total of nine patients, including our own patient, have been described with tumors of the female genital tract (Table 2). Eight of these patients had cystic epithelial neoplasms or cystic lesions of the uterine adnexal organs. One patient had an endometrial tumor. Four patients with ovarian cystadenomas have been reported. All occurred in patients less than 20 years of age. Unfortunately, the descriptions of these tumors generally were very limited. An ovarian mucinous cystadenoma in an 18-year-old girl that was presented at the 1992 Minnesota Dermatological Meeting may have been the first case described, according to Cohen and his associates (6). In 1993, Scovby et al. reported an ovarian serous cystadenoma found at autopsy in an 11-year-old girl (12). Two years later, Gordon et al. reported a case of a 6 year, 3 month old girl who had bilateral ovarian serous cystadenomas “with focal nuclear atypia” that “invaded the right fallopian tube” (11). The single published photomicrograph suggests the tumor may have been a papillary endometrioid cystadenomatous neoplasm, rather than a serous tumor. The authors commented that the nuclear atypia “may represent malignant change.” Without an opportunity to examine the histologic slides, we cannot exclude the possibility that it may have been a borderline tumor. Another example of bilateral ovarian serous cystadenomas occurred in a 5-year-old who was reported to have been presented by Boccone and associates at a 1997 Genetics Meeting in Spoleto, Italy (7).

Because ovarian cystic epithelial tumors are typically found in adult women, the finding of ovarian cystadenomas, especially when bilateral, before the end of the second decade of life has diagnostic value in Proteus syndrome (Table 1) (1, 7). In this context, the findings in our patient are particularly interesting. Although her genital tract tumors were paraovarian, rather than ovarian, they were bilateral and cystic. Importantly, the patient was 3 years old when the tumors were diagnosed. Our case is the first documented example of a borderline (LMP) mullerian-type cystic epithelial tumor of the uterine adnexae. Our case suggests that the list of specific tumors found in children and adolescents that are of diagnostic importance for Proteus syndrome should be expanded to include bilateral cystic tumors of the broad ligament or paraovarian region and should include borderline epithelial tumors as well as benign cystadenomas.

Ovarian cysts are also listed among the uncommon “tumors” occurring in Proteus syndrome (6, 7, 11). Three cases have been reported. The patient described by Kousseff required surgery at age 3.5 years to remove a cyst measuring 5.3 × 4.2 cm that was not accompanied by sexual precocity (13). A second patient had bilateral ovarian cysts of unknown size discovered and removed along with multiple meningiomas at ages 16 to 21 years (14). The third patient had a hysterectomy for uterine leiomyomas and ovarian “cysts” of unknown size and laterality at age 30 years; subsequently, she had a meningioma removed (15). None of the cysts in these three cases was classified as to whether they were functional follicle-related cysts or epithelial cysts, and no photomicrographs were published. It is possible that some or all were actually cystadenomas. A single case of uterine endometrial carcinoma in a 23 year old woman has also been reported (2).

A relatively large number of uncommon “tumors” also have involved the male genital tract. A total of six patients have been reported (Table 3). Unfortunately, photomicrographs of the tumors were published in only three of the case reports (11, 16, 17). Hornstein et al. reported two male patients with Proteus syndrome (18). Their Case 1 had an orchidectomy at age 14 years for a right paratesticular tumor. A 4.0 × 3.5 cm friable papillary mass was found attached to the surface of a normal-sized testis adjacent to the epididymis. Microscopy showed a papillary neoplasm composed of delicate fronds lined by ciliated columnar epithelium (no photomicrographs provided), and a diagnosis of “papillary adenoma of the appendix testis” was made. Their Case 2 was a 4-year-old boy who had a testicular tumor that was treated by radical orchiectomy and combination chemotherapy for 1 year. The tumor was a “crescent-shaped noncystic mass 2.5 × 1.5 × 0.5 cm separated from normal testicular tissue by a collagenous capsule.” It was diagnosed as a yolk sac tumor, but also described later in the report as a “papillary adenocarcinoma, a yolk sac tumor, but origin from the rete testis or epididymis could not be ruled out.” Perhaps the authors regarded a yolk sac tumor as a type of papillary adenocarcinoma. In some subsequent review articles, this tumor was listed as a “papillary adenocarcinoma” without mention of yolk sac tumor (7, 11). While gonadal yolk sac tumors were sometimes classified as adenocarcinoma several decades ago, this is no longer done as they are now known to be a specific type of germ cell tumor. The patient was alive, presumably without recurrent tumor, 4 years later. Without microscopic slides, photomicrographs or serum tumor markers (e.g., alpha-fetoprotein) to review, the diagnosis in Case 2 is open to question.

Nishimura and Kozlowski reported epididymal cysts in a 12-year-old boy that were reported as “epididymal cystadenoma” (19). At age 17 years, the patient had a large cystic renal mass diagnosed as a “papillary adenoma of the kidney.” The same patient was also reported by Bale and associates 3 years later (16). In contrast to practically all of the previously reported cases of genital tract tumors in Proteus syndrome, their article had relatively extensive pathological descriptions of the patient's tumors. The epididymal cysts were bilateral (4.5 cm and 2.6 cm) and had “a simple low columnar lining with areas of papillary proliferation into the lumen and occasional glands in the wall.” The illustrated papillae were very short with little, if any, branching or epithelial proliferation. The resected renal lesion consisted of a hydronephrotic kidney with an attached large cyst (22 × 12 cm) that did not communicate with the dilated pelvicalyceal system. The cyst lining had focal areas up to 2 × 1.5 cm of short blunt folds that consisted of broad fibroepithelial papillae. Adjacent to atrophic tubules and glomeruli there was a focus of “glandular proliferations of clear cuboidal cells strongly resembling seminal vesicle and prostate,” as well as large bundles of smooth muscle. Immunostains for prostate-specific antigen and prostatic acid phosphatase were negative. The authors raised the possibility of a congenital malformation or a hamartomatous overgrowth of some part or vestige of the urogenital tract.

At age 22 years, this patient had a mengiothelial meningioma (3 cm) containing a central patch of adipose tissue removed from the middle fossa. Two years later, a 3 × 2.5 × 2 cm testicular tumor was excised. Microscopically, it was about one-third microcystic and two-thirds solid, appearing to arise in and be confined to the rete testis. The microcystic areas contained “narrow fingers of fibrous tissue covered by low cuboidal epithelium” with “cuboidal and columnar epithelium budded into the lumen of dilated rete tubules.” The solid areas consisted of “pale epithelial cells forming gland-like structures and small whorls of slightly spindling cells.” Occasional cellular hyperchromatic foci raised the question of a cystadenocarcinoma of the rete testis. Immunostains for alpha-fetoprotein, human chorionic gonadotropin and carcinoembryonic antigen were negative. Because mitotic figures were rare, an image analysis showed a DNA diploid distribution and an electron-optic study displayed two cells types characteristic of rete epithelium, the lesion was considered to be a rete adenoma or possibly a florid adenomatous hyperplasia. A consultant pathologist favored an adenoma but could not exclude “early malignant change.” No recurrence developed during a follow-up period of 24 months.

Two boys had tumors interpreted as mesothelioma involving the genital tract. One was a 51 month old boy who developed an acutely painful tumorous left testicle accompanied by a hydrocele. The testicle and two intraabdominal cysts containing 100 mL of greenish fluid were removed. Histologic examination showed a papillary and tubular tumor with psammoma bodies that was diagnosed as a “highly differentiated papillary mesothelioma” of the tunica vaginalis (17). The size of the tumor was not stated and the histologic features of the cysts were not provided. The authors regarded the tumor as a “confirmed malignancy,” although no follow-up was provided. In a later report, the patient's musculoskeletal manifestations at the age 5 years were detailed and no mention was made of any recurrence of the tumor (20). Commenting on this patient, Bale et al. suggested that the tumor may have been a papillary tumor of the rete testis similar to the lesion found in their patient (see above) (16), even though the testis itself was described as atrophic. A variant of paratesticular papillary serous borderline tumor is also a remote possibility.

The other patient had a “papillary neoplasm, most likely of mesothelial origin” found at autopsy in a 5 year, 7 month old involving the inferior surface of the diaphragm, omentum, pelvis, mesenteric lymph nodes and the scrotum (but not infiltrating the testes) (11). Psammoma bodies were present. The authors also considered the possibility of metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma, but this is implausible in view of the findings at autopsy and the histologic features seen in the single published photomicrograph. Lastly, Biesecker described one case of a “cystic adenoma of the tunica albuginea” in a 5-year-old boy (1). While no details of the tumor were provided, it was later described in the report as “histologically similar to the ovarian cystadenomas” that occur in Proteus syndrome.

CONCLUSION

It is unfortunate that the pathologic findings of the genital tract “tumors” in so many of the previously reported cases were limited. In some cases, the diagnosis rendered may be in doubt. We hope that future reports of tumors in patients with Proteus syndrome will have better documentation of the pathologic aspects of the lesions. We suspect that specific testicular and paratesticular tumors may prove to have the same diagnostic value in Proteus syndrome as the ovarian and paraovarian lesions. In view of the frequent papillary and cystic aspects of many of these tumors and the questionably malignant or borderline histologic features in some of them, these genital tract tumors may prove to be histogenetically related neoplasms.

References

Biesecker LG . Multifaceted challenges of proteus syndrome. JAMA 2001; 285: 2240–2243.

Cohen Jr MM . Overgrowth syndromes: an update. Adv Pediatr 1999; 46: 441–491.

Happle R . Cutaneous manifestation of lethal genes [Letter]. Hum Genet 1986; 72: 280.

Happle R . Lethal genes surviving by mosaicism: a possible explanation for sporadic birth defects involving the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol 1987; 16: 899–906.

Biesecker LG, Happle R, Mulliken JB, et al. Proteus syndrome: diagnostic criteria, differential diagnosis, and patient evaluation. Am J Med Genet 1999; 84: 389–395.

Cohen Jr MM . Proteus syndrome: Clinical evidence for somatic mosaicism and selective review. Am J Med Genet 1993; 47: 645–652.

Cohen Jr MM, Neri G, Weksberg R . Overgrowth syndromes. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001.

Tibbles JA, Cohen Jr MM . The Proteus syndrome: the Elephant Man diagnosed. Br Med J 1986; 293: 683–685.

Cohen Jr MM, Hayden PW . A newly recognized hamartomatous syndrome. Birth Defects 1979; 15: 291–296.

Wiedemann HR, Burgio GR, Aldenhoff P, Kunze J, Kaufmann HJ, Schirg E . The proteus syndrome. Partial gigantism of the hands and/or feet, nevi, hemihypertrophy, subcutaneous tumors, macrocephaly or other skull anomalies and possible accelerated growth and visceral affections. Eur J Pediatr 1983; 140: 5–12.

Gordon PL, Wilroy RS, Lasater OE, Cohen Jr MM . Neoplasms in proteus syndrome. Am J Med Genet 1995; 57: 74–78.

Skovby F, Graham Jr JM, Sonne-Holm S, Cohen Jr MM . Compromise of the spinal canal in proteus syndrome. Am J Med Genet 1993; 47: 656–659.

Kousseff BG . Pleiotropy versus heterogeneity in proteus syndrome [letter]. Pediatrics 1986; 78: 544–546.

Bouzas EA, Krasnewich D, Koutroumanidis M, Papadimitriou A, Marini JC, Kaiser-Kupfer MI . Ophthalmologic examination in the diagnosis of proteus syndrome. Ophthalmology 1993; 100: 334–338.

Maassen D, Voigtlander V . Proteus-syndrome. Der Hautarzt 1991; 42: 186–188.

Bale PM, Watson G, Collins F . Pathology of osseous and genitourinary lesions of proteus syndrome. Ped Pathol 1993; 13: 797–809.

Malamitsi-Puchner A, Dimitriadis D, Bartsocas C, Wiedemann HR . Proteus syndrome: course of a severe case. Am J Med Genet 1990; 35: 283–285.

Hornstein L, Bove KE, Towbin RB . Linear nevi, hemihypertrophy, connective tissue hamartomas, and unusual neoplasms in children. J Pediatr 1987; 110: 404–408.

Nishimura G, Kozlowski K . Proteus syndrome (report of three cases). Australasian Radiol 1990; XXXIV: 47–52.

Demetriades D, Hager J, Nikolaides N, Malamitsi-Puchner A, Bartsocas CS . Proteus syndrome: musculoskeletal manifestations and management: A report of two cases. J Ped Orthopaedics 1992; 12: 106–113.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. M. Michael Cohen for his invaluable aid in gathering data for the literature review and Mrs. Patricia Matkovic for her secretarial assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Raju, R., Hart, W., Magnuson, D. et al. Genital Tract Tumors in Proteus Syndrome: Report of a Case of Bilateral Paraovarian Endometrioid Cystic Tumors of Borderline Malignancy and Review of the Literature. Mod Pathol 15, 172–180 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880510

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880510